Looking Back at the Camera: How Controversial AI Firms Shaped Delhi’s Predictive Policing

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

Read the first part of this series here.

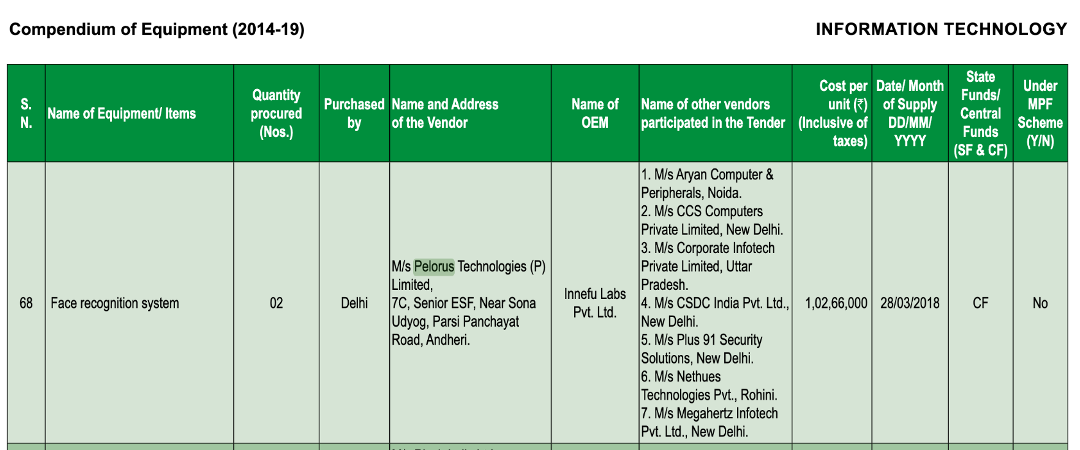

New Delhi: The Bureau of Police Research and Development, in its Compendium of Equipment (From April 2014 to March 2019), Volume II, noted that the Delhi Police bought two facial recognition systems on March 28, 2018. While the software was originally manufactured by Innefu Labs Pvt Ltd, it was supplied to the Delhi Police by a vendor named Pelorus Technologies Pvt. Ltd. Both of these companies – and others who have sold AI technology to the Delhi Police – are worth looking into. An investigation by Amnesty International has linked Innefu Labs to the illegitimate use of spyware against human rights activists elsewhere in the world.

Tender documents obtained through a Right to Information (RTI) response revealed that the two facial recognition systems – (01 Static and 01 Portable) – were supplied to the Delhi Police’s Crime Unit for two purposes. First, to match missing persons with unidentified persons found. Second, to compare criminal photographs/portraits seized/prepared during investigations with online criminal dossier systems.

According to the supply order sent from the Office of the Deputy Commissioner of Police, Prov. & Logistics, Delhi, these systems cost a total of Rs 1,02,66,000 (roughly $1,20,000), which was spent from the central funds of the Indian government.

Apart from this, Pelorus Technologies was also awarded a two-year comprehensive annual maintenance contract at a cost of Rs 16,99,200 for two years – Rs 8,49,600 per annum – including GST after the expiry of the three-year warranty.

Screengrab from Compendium of Equipment (From April 2014 to March 2019), Volume II, stating that Pelorus Technologies supplied two facial recognition systems, manufactured by Innefu Labs, to the Delhi Police.

Innefu Labs Pvt. Ltd has also published a detailed report on their collaboration with the Delhi Police – ‘Case Study Delhi Police’ – which confirms these details. Another post about AI Vision – the facial recognition system designed by Innefu Labs – states, “Delhi police also used the same product [AI Vision] to identify potential rioters in the 2020 North East Delhi riots. The product achievement found its mention in the parliamentary speech of Hon. Home Minister Mr. Amit Shah while discussing the Delhi riots.” The post further claims, “During the first four days of its implementation, Innefu’s product [AI Vision] helped in identifying 3000 missing children. National Commission for Protection of Child Rights also advocated the use of this software to help trace missing children.”

On March 12, 2020, Union home minister Amit Shah informed parliament that 1,922 perpetrators of the Northeast Delhi riots had been identified using facial recognition on the video footage received from the public.

Innefu Labs: The manufacturer

Innefu Labs describes itself as an “AI-driven company developing cutting-edge technology to carry out Predictive Intelligence and Cyber Security solutions.” According to its website, the company’s “intelligent biometric and facial recognition software is being used in multiple organisations across India & the Middle East” and its “AI-based data analytics & Machine Learning solutions are in use with multiple Law Enforcement Agencies across Asia”.

An investigation by The Wire into the background of Innefu Labs has revealed multiple allegations implicating the company in serious human rights violations.

Case 1: Attack on a human rights activist in Togo

In 2021, Amnesty International uncovered a targeted digital attack campaign against a prominent human rights activist in Togo, West Africa. According to the findings, the activist was targeted in late 2019 and early 2020 using spyware deployed on both Android and Windows devices.

An investigation by Amnesty International Security Lab found that the spyware used in these attack attempts is tied to an attacker group known in the cybersecurity industry as the Donot Team, which has previously been connected to attacks in India, Pakistan and neighbouring countries in South Asia. Digital records identified during this investigation revealed that hundreds of individuals across South Asia and the Middle East were targeted using the Donot Team’s Android spyware.

The investigation also exposed a link between the Donot Team spyware and a company supplying AI-based predictive policing tools to Indian law enforcement agencies. The company was Innefu Labs Pvt. Ltd.

Key evidence linking Innefu Labs to the spyware

Amnesty International found two key pieces of evidence connecting Innefu Labs to the Donot Team Android spyware and to the specific infrastructure used to deliver the Android spyware to the activist in Togo.

- Investigators found a screenshot from an infected test Android phone exposed on a Donot Team server. The screenshot contained two keyboard suggestions – URLs – one of which was an IP address tied to Innefu Labs. The Innefu Labs IP address would only be suggested by the keyboard if the attacker using the test phone had previously interacted with it.

- The same Innefu Labs IP address was recorded in log files left publicly exposed on the bulk[.]fun website which was used to distribute Donot Team spyware.

This is significant as it shows that the Innefu Labs IP address was not only linked to the testing of the Donot Team Android spyware, but also to the specific internet infrastructure involved in the distribution/deployment of some of the spyware tools which have been previously linked to the Donot Team. The Amnesty International report states, “The technical evidence suggests that Innefu Labs is involved in the development or deployment of some Donot Team spyware tools. These tools may then be used by a range of hacker-for-hire actors, which are grouped under the 'Donot Team' cluster.”

The report, however, clarifies that there is no sufficient evidence to indicate whether Innefu Labs had any direct involvement or knowledge of the targeting of the Togolese activist. It notes, “Although the Innefu Labs IP address is connected to both the spyware distribution website and the Donot Team spyware, Innefu Labs may not necessarily know how any third parties are using these spyware tools.”

Nonetheless, the report underscores the broader concern: “This case highlights the threat 'hacker-for-hire'-type attacks pose to human rights defenders and civil society globally. ‘Hacker-for-hire' attacks are offensive cyber operations performed by a threat actor (“a hacker”) normally on behalf of paying customers. These customers may include domestic government agencies, foreign governments or commercial entities.”

It further observes that multiple “hacker-for-hire” companies have advertised themselves as “legitimate cybersecurity services while covertly carrying out offensive digital attacks for their clients.”

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

Innefu Labs’ response

In response to the queries sent by Amnesty International, Innefu Labs denied any knowledge of the Donot Team and stated that it had not exported digital surveillance tools or services to any country, including authorities in Togo.

However, the company also acknowledged that it does not have a human rights policy. When asked whether it follows any process for carrying out human rights due diligence, Innefu Labs did not provide any information.

Amnesty International notes, “That companies like Innefu Labs and BellTroX [another Indian cybersecurity company linked to several attacks] are operating in India without adequate regulation is a serious concern for human rights.” It also points out that India, as a member of the Wassenaar Arrangement – a voluntary export control regime of 42 nations committed to regulating the transfer of conventional weapons and dual-use technologies – has pledged to implement export controls on targeted surveillance technologies.

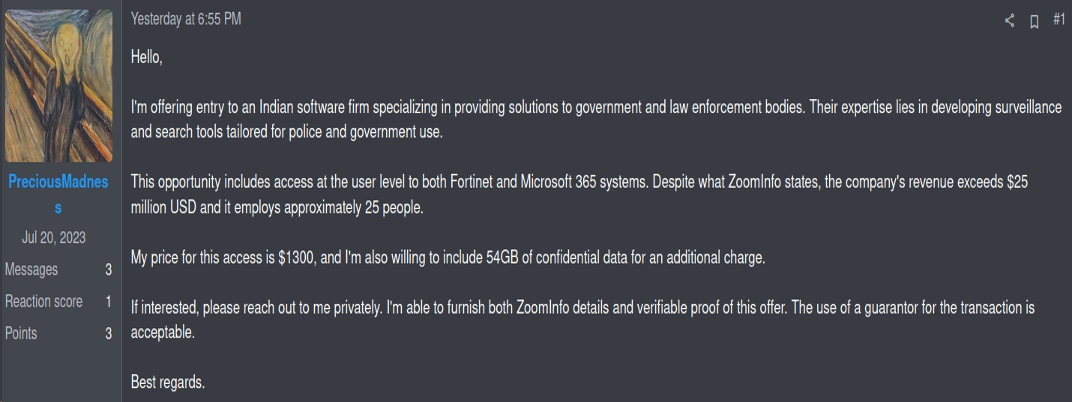

Case 2: A major data breach

In January 2024, a hacker operating under the alias ‘PreciousMadness’ claimed on the Russian Anonymous Marketplace (RAMP) – a forum on the dark web – to have gained unauthorised access to Innefu Labs’ internal systems. The hacker's offering included (a) unauthorised access to crucial components of Innefu’s infrastructure, such as Fortinet VPN and Microsoft 365 Services, priced at $1,300; and (b) 54 GB of exfiltrated data, available at additional cost. ‘PreciousMadness’ also advertised the same unauthorised access on other platforms like XSS and Exploit Forums.

An investigation done by The Cyber Express (a cybersecurity news publication) with the help of multiple independent researchers revealed, “The data breach at Innefu Labs has led to the exposure of sensitive information belonging to various Indian and overseas entities. This includes individuals, major conglomerates, politicians, and even agencies of the Indian government.”

Screengrab from the Russian Anonymous Marketplace (a forum on the Dark Web) detailing a hacker under the name “Precious Madness” offering unauthorised access to Innefu Lab’s internal systems.

A pressing question emerges: Why do the Delhi Police continue to collaborate with Innefu Labs – a company with a troubling history, including a data breach allegedly carried out by the hacker ‘PreciousMadness’ and reported links to targeted surveillance technologies such as the Donot Team spyware?

Despite multiple attempts to secure an interview and the submission of detailed queries, Innefu Labs CEO Tarun Wig declined to respond.

| Other tools provided by Innefu Labs In addition to facial recognition software, Innefu Labs provides a suite of tools designed to support law enforcement operations. In a blog post titled ‘Radicalisation on social media’, the company notes that its social media monitoring tools “analyse online behaviour patterns” and deploy Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) to track the preferences, interests, opinions, etc. of “individuals who may be at the risk of being radicalised”. The post further states that this monitoring can, later, “help in developing selected interventions”. One such tool, Innsight – described as a “big data OSINT tool built on AI-ML capabilities” – is deployed by law enforcement and intelligence agencies to “track and analyse open channels of mass communication for surveillance and intelligence gathering”. As stated on the company’s blog, “Innsight is actively helping our clients to identify key actors behind protests or riots, daily monitoring of social media activities, bot analysis, link analysis for network detection, and social media reports.” Innefu Labs has listed Delhi Police, Tamil Nadu Police, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) as the featured customers of its Innsight tool on LinkedIn. The company has advertised Innsight as “one tool for 360-degree profiling of people, post-event analysis by ingesting data from social media, leaked databases, WhatsApp groups and Telegram channels to identify key influencers”. In a separate blog post, Innefu Labs asserts that the OSINT analysis conducted through Innsight uncovered “unforeseen propaganda in action” during the Citizenship (Amendment) Act/National Register of Citizens protests. The post further claims, “It was discovered that the issue was appropriated by foreign forces to destabilise the harmony of the country and the government, thereby creating internal conflict. Pakistan is recorded to be the hotspot and point of origin of anti-India narrative, calling India a ‘Terror State’ and ‘Nazi.’ Bots and trolls are being used as pawns to peddle misinformation, and rumours are also being circulated about Police brutality and the concentration camps in India.” An intelligence report by the company, titled ‘CAB 2019: Mass Polarisation over Social Media’, identifies key international influencers and personalities “taking a negative stance on the bill while influencing the general public sentiment”. The report details how Innefu’s tools assisted the police in uncovering the ‘polarisation’ surrounding the CAA, stating that the protests aimed “to not only spread a negative image of India globally but to also create internal proxy war, propaganda videos and information of Indian Police Brutality”. |

Pelorus Technologies: The supplier

Pelorus Technologies, a Mumbai-based company, is a distributor of specialised digital forensics, intelligence and surveillance technology to law enforcement agencies, governments and private enterprises. It supplies Delhi Police with the facial recognition system developed by Innefu Labs. In addition to this, Pelorus Technologies markets several other Innefu products like Call Data Record (CDR) Analysis Software, and describes Innefu Labs as its in-house software development and research wing.

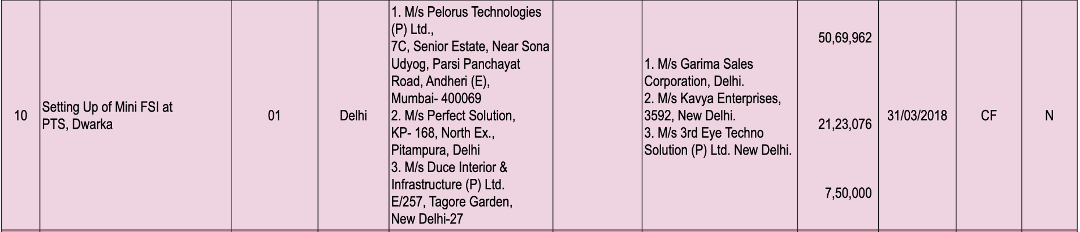

In March 2018, Pelorus Technologies also helped the Delhi Police in setting up a Mini Forensic Science Institute lab at the Police Training School in Dwarka, Delhi. As mentioned in the Compendium of Equipment (2014-19), Volume I by the Bureau of Police Research and Development, Pelorus Technologies won the contract of Rs 50,69,962 from the central funds of the Government of India.

Screengrab from Compendium of Equipment (2014-19), Volume I stating that Pelorus Technologies won a contract to set up a Mini Forensic Science Institute lab at the Police Training School in Dwarka, Delhi.

Other forensic and surveillance tools used by the Delhi Police

The Delhi Police also deploy a variety of other forensic and surveillance tools, many of which have been repeatedly linked with allegations of human rights violations. The Union government’s decision to collaborate with the companies manufacturing these tools – detailed below – could have serious implications on the future of policing in India and the nature of companies that will be entrusted with supplying AI and forensic technologies to law enforcement agencies.

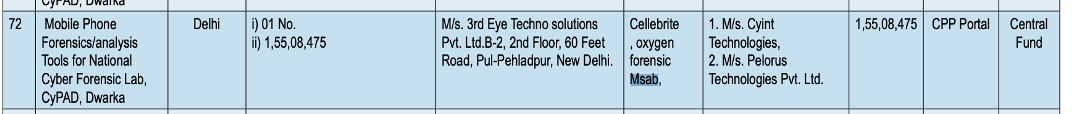

According to the Compendium of Equipment (April 2019 to March 2020) — Volume II, published by the BPR&D, the mobile phone forensics and analysis tools manufactured by Swedish firm MSAB, Israeli company Cellebrite and Russia’s Oxygen Forensics were sold to the National Cyber Forensic Lab by a third-party distributor named 3rd Eye Techno Solutions. Like Pelorus and Innefu Labs, these companies too have international track records that could raise eyebrows.

Screengrab from Compendium of Equipment (From April 2014 to March 2019), Volume II stating that mobile phone forensics and analysis tools manufactured by MSAB, Cellebrite and Oxygen Forensics were sold to the National Cyber Forensic Lab, Delhi by 3rd Eye Techno Solutions.

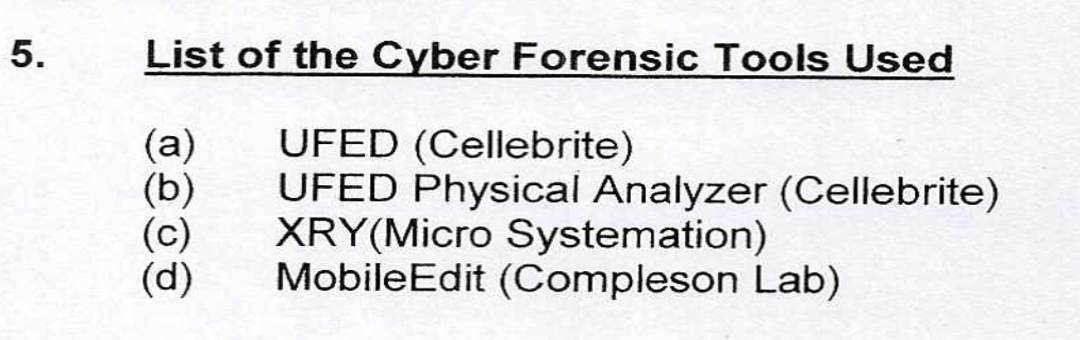

In connection with the Ratan Lal murder case, the Delhi Police received a report from the Cyber Forensics Lab at CERT-In on the analysis of digital evidence such as mobile phones, hard drives and other electronic devices. The report – titled ‘Digital Forensic Data Retrieval & Analysis Report’ and accessed by The Wire – listed MSAB’s XRY and Cellebrite’s Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED) and UFED Physical Analyser among the cyber forensic tools employed by CERT-In during the investigation.

Screengrab from CERT-In report associated with the Ratan Lal Murder Case stating that MSAB’s XRY and Cellebrite’s UFED and UFED Physical Analyser were among the cyber forensic tools employed during the investigation.

| In March 2025, the Ministry of Home Affairs approved a request by the Delhi Police to exempt several such technologies from the Make in India clause. This exemption permits the procurement of these products from foreign vendors, bypassing the usual preference for domestic suppliers. Such waivers are typically granted when equivalent goods or services are not readily available from Indian manufacturers or when certain eligibility criteria are not met. The tools approved for exemption included a range of high-powered forensic and surveillance technologies sourced from global vendors: 1. MSAB’s extraction software XRY 2. Two tools from Israeli giant Cellebrite: (1) UFED 4PC and (2) Digital Collector and Inspector. 3. Detective by the Russian company Oxygen Forensics 4. MOBILEdit by the Czech firm Compelson Labs 5. Two tools from the Canadian company Magnet Forensics: Axiom and Outrider 6. Tools from Netherlands-based Foclar: Impress and Mandate 7. Evidence Center by US-based Belkasoft 8. Recon ITR and Recon Lab from the American firm Sumuri 9. OSForensics from the Australian company PassMark Software |

Cellebrite and its troubling human rights record

The Delhi Police make extensive use of Cellberite’s mobile and cyber forensic tools. The Israeli giant, Cellebrite, is a digital forensics company that develops technologies enabling law enforcement agencies, enterprise firms, and service providers to collect, review, analyse, and manage digital data. Its flagship product line, the Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED), is widely used for mobile phone data extraction and analysis.

Founded in 1999, Cellebrite claims to serve “6,900 customers across federal, state, local, and enterprise sectors, including 90% of relevant public safety agencies.” According to the company, its tools have been used in over 5 million investigations across the globe.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

However, Cellebrite’s products have repeatedly been at the centre of international controversy. They have allegedly been deployed by several authoritarian regimes to facilitate unauthorised surveillance, suppression of dissent, and human rights abuses.

- In December 2024, Amnesty International reported that Serbian police and intelligence services used Cellebrite’s UFED tools to unlock the phones of journalists and activists. Thereafter, a spyware – identified as NoviSpy – was allegedly installed during detention to enable remote surveillance and full access to devices, including camera and microphone control.

- In 2021, Botswana police reportedly used Cellebrite technology on multiple occasions to extract data from the phones of journalists, student activists and opposition leaders.

- According to reports by the Committee to Protect Journalists and the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, the head of Russia’s Investigative Committee stated that in 2020, law enforcement agencies had probed cellphones 26,000 times the previous year using Cellebrite’s data extraction tools. Thereafter, in 2021, Cellebrite announced that it had stopped selling to Russia and Belarus, but Russian investigative agencies continued to reference the company’s products in official reports and training materials as late as 2022.

- In July 2020, during a court hearing, filings by the Hong Kong police revealed that Cellebrite’s phone hacking technology had been used to break into 4,000 phones of Hong Kong citizens, including prominent pro-democracy politicians and activists.

- In Bahrain, authorities allegedly used UFED to extract private WhatsApp messages and photos from the phone of a political activist shortly after his arrest in 2013. The extracted data – marked “evidence” in his trial – was presented by Bahraini prosecutors and played a key role in his conviction, despite his claims of having been tortured in custody.

The list goes on. Cellebrite’s phone extraction tools have also drawn sharp criticism from privacy advocacy groups worldwide, many of whom have called for moratoriums on their use due to the ease with which they can extract personal data from smartphones.

MSAB: Another controversial vendor

Headquartered in Sweden, MSAB is a renowned world leader in mobile forensic technology, supported by a global network of distributors. Its flagship software, XRY, enables the extraction and analysis of data such as contacts, call logs, pictures, SMS, MMS and application data from mobile devices.

XRY has faced widespread criticism for its role in digital privacy breaches and its potential use in surveillance attacks on human rights activists and journalists. The technology can retrieve passwords and authentication tokens, enabling authorities to remotely access users' online accounts such as Google, Facebook, cloud storage services and more. Therefore, the software is widely used by law enforcement and intelligence agencies, military organisations, and forensic laboratories in over 100 countries worldwide, including India.

MSAB's role in crackdown on protesters in Myanmar

Media reports indicate that MSAB’s technology has allegedly been used by Myanmar’s security forces to extract data from the mobile phones of protesters, activists, journalists and civilians.

Thousands of people were arrested, charged or sentenced as part of the crackdown on nationwide protests in Myanmar following the 2021 military coup. According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, a Myanmar civil society group, “Some of them may have had information extracted from their phones by security officers using digital forensic technology bought from Western companies before the coup.”

MSAB confirmed selling its forensic tools to the Myanmar police in 2019. Also, leaked 2019 budget documents from Myanmar’s Ministry of Home Affairs revealed allocations for the procurement of MSAB units for the 2020–2021 fiscal year. According to the notations in the budget, as reported by The New York Times, those MSAB field units could download the contents of mobile devices and recover deleted items.

In response to these allegations, MSAB has said that limited technology was sold to police working for a civilian government and that the licenses for these forensic devices were cancelled after the 2021 coup. However, its earlier products (sold in 2019) still remain in the hands of Myanmar’s security forces, and MSAB’s own website states that its products can be used even with an expired license.

Massive data leak involving Cellebrite and MSAB

In January 2023, a total of 1.83 terabytes of data was leaked from two leading digital forensics companies – Cellebrite and MSAB. By that time, the Delhi Police had already partnered with both companies and had begun using their tools.

The data was reportedly shared with the hacktivist collective Enlace Hacktivista by an “anonymous whistleblower”. Approximately 1.7 terabytes of the total leaked data belonged to Cellebrite, and another 103 GB to MSAB. It was believed to include system information, technical documentation and some customer-related documents. However, the leaked data did not appear to contain specific client identities.

Enlace Hacktivista issued a statement saying, “An anonymous whistleblower sent us phone forensics software and documentation from Cellebrite and MSAB. These companies sell to police and governments around the world who use them to collect information from the phones of journalists, activists and dissidents. Both companies’ software is well documented as being used in human rights abuses.”

In response, an MSAB spokesperson denied any breach, stating: “MSAB has not been hacked. All customer data is safe, and so are all systems, code, or information internal to MSAB.”

Despite the scale of the alleged breach, the Delhi Police did not sever ties with either firm. In fact, as recently as January 2025, the Ministry of Home Affairs approved a request from the Delhi Police to exempt Cellebrite and MSAB tools, among others, from the Make in India procurement clause, paving the way for continued purchases.

Pelorus Technologies’ partnership with Cellebrite and MSAB

Pelorus Technologies is a key partner of Cellebrite’s and was recently honoured with the “Outstanding Partner Excellence Award – APAC” by the company. Pelorus Technologies also lists a range of Cellebrite tools among its mobile forensics offerings. Their partnership is confirmed by Cellebrite's official website, which refers to Pelorus Technologies as their "channel partner" for Milipol India 2025 – an international event on homeland security supported by the Ministry of Home Affairs.

In early 2021, Pelorus Technologies also announced a strategic collaboration with MSAB. As its national distributor for India, Pelorus is responsible for delivering MSAB’s advanced digital intelligence solutions to the Indian investigative and law enforcement agencies.

Highlighting his company’s association with MSAB, Pelorus Technologies CEO Dwivedi told the media in February 2021, “MSAB’s focus is on helping investigative agencies with improved data collection and analysis. At Pelorus, we are also keen to improve intelligence technology available in the country to create safer communities. Thus, our goals are the same – making the world a safer place to live in.”

When asked about the collaboration despite MSAB’s controversial background, Dwivedi told The Wire, “The companies we collaborate with have to be credible, have to be doing the right thing, should not have to have a history of doing any wrong. We tie up with them only if they do not have a history of supporting any illegal thing in the world.” He added, “What we understand is that MSAB banned Myanmar four years ago, and they are not supplying any equipment for Myanmar anymore.”

About the concerns around data privacy, Dwivedi said, “We never get into the privacy part. Once we apply to law enforcement agencies, it is their responsibility to handle it with proper care and not do illegal things.”

The Wire pulled a list of shipments imported by Pelorus Technologies Ltd. Using the commercial intelligence platform Sayari, we tracked these shipments, categorised as "computers and data processing machines."

Our investigation identified 118 shipments from Cellebrite Asia Pacific (a Singaporean subsidiary of Cellebrite) and an additional 23 shipments from MSAB, as of June 09, 2025 — both companies often tied to supplying surveillance and digital forensics tools.

Image/video enhancement tools: The precursor to facial recognition analysis

The images/videos derived from CCTV footage and other private sources during criminal investigations are often of poor quality and require enhancement before any facial recognition algorithms can be applied to them. To bridge this gap, forensic image and video enhancement tools are deployed. One such tool used by the Delhi Police is AMPED FIVE, as confirmed to The Wire by the investigating officer of the Ratan Lal Murder Case, Inspector Gurmeet Singh, Crime Branch, Delhi Police.

AMPED FIVE is designed by AMPED Software, an Italian company founded in 2008 that offers image and video analysis and enhancement solutions for forensic, security, and investigative applications. Its products are distributed through a global network of partners like Pelorus Technologies, which supply them to law enforcement agencies worldwide.

Martino Jerian, founder and CEO of AMPED Software, refused to name the company’s clients, citing “confidentiality agreements and data protection policies”. However, he confirmed to The Wire, “Our products, Amped FIVE and Amped Authenticate, are in use by several Indian law enforcement and forensic units.”

AMPED FIVE is widely known for its advanced image and video enhancement capabilities, including features like noise reduction, sharpening, colour correction and distortion correction, which are valuable for forensic investigations where visual evidence might be crucial.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

During court proceedings related to the Ratan Lal Murder Case, special public prosecutor Amit Prasad admitted using “AMPED software based on digital recognition” to establish the identity of one of the accused. Advocate Uday*, who represents several Delhi riots accused, also confirmed the police’s use of AMPED Software and its reference by the prosecution in court.

In response to concerns over the potential misuse of the company’s tools, Jerian told The Wire over email, “We have licensing terms that prohibit unlawful use, and we reserve the right to revoke access immediately. While we’ve never encountered such a case, we remain alert and ready to act. As per the nature of the products, the possibility of unethical use is remote…we mostly do low-level image processing, without understanding the image's semantic content or doing any kind of face or object recognition.”

However, it remains unclear whether using AMPED’s video enhancement tool as a pre-processing step for facial recognition, especially in cases where the latter may have contributed to wrongful incarceration, would fall under the company’s definition of ‘unethical use’. The Wire sought clarification from Jerian on AMPED’s position on this, and he said, “In your example, we would consider unethical the case where a user intentionally produces wrongful outputs to impair a correct facial recognition.”

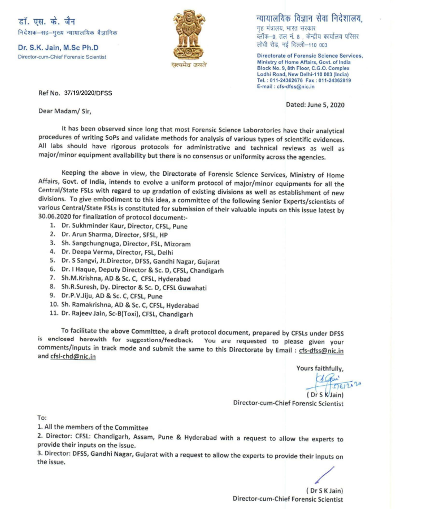

On June 5, 2020, the Directorate of Forensic Science Services under the Ministry of Home Affairs constituted a committee of experts from central and state forensic science laboratories to draft a manual for the establishment and upgradation of forensic science labs across the country. In its recommendations, the committee endorsed AMPED FIVE as a preferred software for the acquisition and analysis of CCTV footage.

Screengrab of a notification from the Directorate of Forensic Science Services outlining the constitution of a committee of experts to draft a manual for the establishment and upgradation of forensic science labs.

Pelorus Technologies lists several AMPED products, including AMPED FIVE, among the tools it supplies to investigative and law enforcement agencies worldwide. Jerian, however, refused to disclose which distributor supplies AMPED’s tools to the Delhi Police.

When asked about the terms of AMPED’s contract with Pelorus Technologies, particularly regarding ethical safeguards, Jerian refused to share specific details. He stated, “Our contracts require full legal compliance, including anti-corruption laws, export regulations, and GDPR-based data protection standards. We also require our distributors to meet the same obligations through our onboarding and audit process.”

It remains unclear how these ethical safeguards accommodate Pelorus Technologies’ partnerships with companies like Cellebrite and MSAB that have faced allegations of human rights violations.

Which databases are connected to Delhi Police’s facial recognition technology?

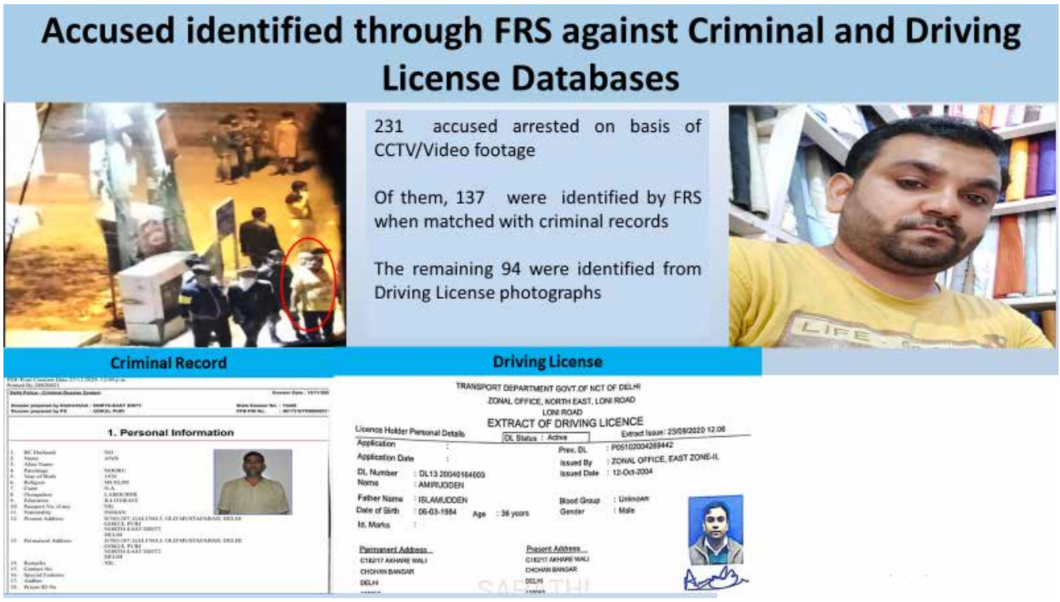

There remains a lack of transparency around the databases used for matching input images in the Delhi Police’s facial recognition system. A 2020 report released by the Delhi Police highlighting their achievements included a chapter titled ‘Investigations into North-East Delhi Riots’, co-authored by Pramod Singh Kushwah, Deputy Commissioner of Police, Special Cell, and Joy Tirkey, Deputy Commissioner of Police.

The chapter outlined the use of video analytics and facial recognition in the investigation, stating: “945 CCTV footage and video recordings were obtained from multiple sources, including CCTV cameras installed on the roads, video recordings from smartphones, video footage obtained from media houses, and other sources were analysed with the help of video analytic tools and facial recognition systems. The photographs therein were matched for multiple databases, which included Delhi Police criminal dossier photographs and other databases maintained by the government. This helped in identifying persons involved in riots, which proved helpful in taking legal action after corroboration with other supporting evidence.”

The report also confirmed the use of the e-Vahan database (a national database of registration details of all vehicles) and driving license databases for further identification. However, the reference to “other databases maintained with the government” in the report remains vague, leaving uncertainty about the full scope of databases accessed by the Delhi Police’s facial recognition systems. According to police officials who spoke to The Wire, the Election Commission of India’s electoral roll — the database linked to the Electoral Photo Identity Card (EPIC) — was also used to identify suspects in Delhi Riots cases.

The report also does not offer any information on data retention practices, such as how long the processed images are stored for, raising further concerns about privacy safeguards and potential misuse.

Screengrab from chapter ‘Investigations into North-East Delhi Riots’ of the police report (2020) “Delhi Police: Rising to the Challenge.”

In February 2021, then Delhi Police Commissioner S.N. Shrivastava addressed the media at an annual press conference at Delhi Police headquarters. Detailing the role of technology in the investigation of the 2020 Northeast Delhi riots, he said, “231 of the 1,818 arrests [total] so far had been made possible using the latest technological tools. Of 231 such arrests, 137 persons were identified through our facial recognition system. The FRS was matched with police criminal records, and many accused were caught. Over 94 accused were identified and caught with the help of their driving license photos and other information.”

Srinivas Kodali, a data and privacy researcher, spoke to The Wire about the vast and often opaque mechanisms through which the Delhi Police and other law enforcement agencies access digitised personal data. He said, “Once data is digitised, law enforcement agencies can access it in one way or another, either directly or by requesting it under various legal provisions. Several laws explicitly grant such access. For example, the Registration of Births and Deaths Act maintains a structured list of records, while the Telecom Act provides authorities with access to a wide range of telecommunications data, including call data records, internet protocol data records, and tower data records. Additionally, under the Sarais Act of 1867, police are authorised to collect hotel check-in data. This means that when a guest submits a photograph for identification at a hotel in Delhi, that information can be shared with the Delhi Police. In essence, any form of digitised data – whether personal records, communication logs or travel details – either remains directly accessible to law enforcement or can be lawfully demanded by them.”

He highlights the extensive reach of digital surveillance mechanisms in India by citing an example of the Disha Ravi case, where “authorities leveraged the Information Technology (IT) Act to demand access to a Google Document shared between climate activists Disha Ravi and Greta Thunberg during the farmers’ protests. This allowed them to trace and identify every individual who had contributed to the document.”

When it comes to facial recognition and surveillance, he adds, “authorities may seek access to extensive photographic databases, with electoral data being one of the most significant. The EPIC (Electoral Photo Identity Card) database contains photographs of nearly every Indian voter, making it one of the largest repositories. Other key databases include the passport database and the UIDAI (Aadhaar) database, which store photographs and biometric data.”

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

In a parliamentary address on March 12, 2020, home minister Amit Shah responded to concerns over alleged violations of the right to privacy during the investigation into the 2020 Delhi communal violence. He stated that the “Delhi Police has not used Aadhar data for facial recognition of perpetrators, and while the Government respects the right to privacy, it cannot supersede the quest for bringing perpetrators of riots to justice.” He further said, “The Delhi Police has abided by the Supreme Court's guidelines on right to privacy during the course of investigation.”

However, Kodali explains how the law enforcement agencies often circumvent the court rulings on Aadhar data: “Legally, biometric data from Aadhaar is not supposed to be shared with law enforcement, as per Supreme Court and high court rulings. However, these restrictions do not seem to apply to photographs. While UIDAI may not provide direct access to law enforcement, police can still obtain photographs through other channels. For example, KYC (Know Your Customer) processes – whether for land records, banking, or other government services – collect photographs that may be shared with government agencies, which in turn can provide them to law enforcement.”

“Additionally, the Crime and Criminal Tracking Networks and Systems serve as a centralised platform linking various law enforcement databases. It integrates data from the Fingerprint Bureau, which holds extensive fingerprint records, and the prison system, which tracks inmate visits. Beyond police databases, government office access systems in Delhi, controlled by the Ministry of Home Affairs, track individuals entering government buildings, including journalists and RTI applicants. Similarly, DigiYatra, a digital air travel verification system, claims not to share personal data but often shares metadata, which can still be used for tracking. Other sources of data include visa applications, which store photographs, and airport travel records,” says Kodali.

The Wire has reached out to the commissioner, Delhi Police and secretary, Union Ministry of Home Affairs asking a number of questions about the companies whose products are being used, the processes involved, the tools’ accuracy and the companies’ questionable global track record. No response has been received till the time of publication.

Update on July 31, 2025: Response from Innefu Labs

After this article was published, Innefu Labs sent a statement denying any affiliation with the Donot Team. Their full statement is attached below:

“Innefu Labs categorically states that it has no business affiliation or association—direct or indirect—with the Donot Team, nor has it ever engaged in any activities related to the development, sale, or distribution of spyware to them.

The claims made in the article are entirely baseless, factually incorrect, and misleading.Such misinformation not only causes unwarranted harm to the reputation of Indian-origin technology companies but also undermines the objectives of the Government of India's ‘Make in India’ initiative, which champions indigenous innovation, technological self-reliance, and global competitiveness—particularly in cutting-edge domains like artificial intelligence.

Innefu Labs remains steadfast in its commitment to ethical innovation and will continue to play an active role in the advancement of India’s technological landscape.”

*Names of accused persons and their advocates have been changed to protect the identities of the accused.

Astha Savyasachi is an investigative journalist whose work focuses on socio-political and human rights issues in India.

This article went live on July third, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.