Democracy on a Precipice

For 11 years, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and home minister Amit Shah have been nibbling away at the laws that have safeguarded the fundamental freedoms – of thought, speech and action – that were till a decade ago the pillars of our democracy.

Today, that democracy is an emaciated skeleton of its former self, but Modi’s thirst for more, and more, and still more power has still not been slaked. On August 20, Shah introduced a Constitution (Amendment) Bill in Parliament (the 130th since 1950) that, if passed, will allow for the dismissal of any Union or state minister, even a prime minister or chief minister, after he or she has been in jail for 30 days upon being accused of crimes punishable by five or more years in prison.

Modi’s justification, that it is impossible for anyone to govern a state, hold cabinet meetings and oversee the execution of its decisions when he or she is sitting in jail, is naive to the point of absurdity. For if it is passed by the two houses of parliament, this amendment will destroy the distinction between innocence and guilt, and make justice irrelevant.

That will allow Modi to become the absolute ruler of India in much the same way as the Enabling Act of 1933 turned Hitler into Germany’s chancellor for life, and ended democracy in Germany.

The astonished fury of the entire opposition is therefore understandable. But how do Shah and Modi hope to get such a draconian constitutional amendment through two houses of parliament in which, neither by themselves nor with the support of their allies, do they command anywhere near a two-thirds majority? Can they even rely on the continued support of Nitish Kumar and Chandrababu Naidu for a Bill of which, as they must know, they could easily become the future victims?

Modi and Shah must know that they cannot. So the only purpose of the proposed amendment can be to draw a red herring across the trail of the political system to distract it from the mounting evidence that the BJP might have indulged in vote-stealing on a large scale, and cannot therefore be trusted to rule the country any more.

Ever since the BJP came close to losing the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, Modi’s government has stooped lower and lower to ensure that he and his close associates never lose power and become answerable for the crimes they have been accused of committing over the last 23 years.

The route they have chosen is to first stifle, and then destroy, India’s democracy. They have spent the last 11 years doing this, step by step, to the human rights and civic freedoms that the Indian Constitution had guaranteed to every citizen of India.

But that did not prevent the BJP from losing 0.8% of its 2019 vote share in 2024, thereby denying it a majority in parliament and forcing it to team up with allies whom it cannot trust.

So, thanks to the Congress-UPA alliance’s inability – not to speak of the Supreme Court's own refusal – to turn the March 2, 2023 directive of a Constitution bench on the appointment of election commissioners into law, Modi and Shah in the past 14 months have turned their attention to the last freedom that remains. This is the right of the people to decide who will rule them through free and fair elections.

Evidence that suggests people's votes are being stolen in Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha elections has been piling up ever since Rahul Gandhi pointed to the anomalies in the Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha elections at a press conference in February this year.

In it he disclosed that while the Maharashtra electorate had increased by 32 lakh in the five years between the 2019 and 2024 Lok Sabha elections, it had increased by 39 lakh in the five months between the Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha elections in 2024! By contrast, the increase in the size of the electorate during the same period of 2019-20 had been only 11.61 lakh.

For the 2024 Vidhan Sabha elections, he said the Election Commission (EC) listed 16 lakh more voters than the entire adult population of Maharashtra. It could give no explanation for this.

The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) has also accused the BJP of stealing votes. In October 2024, Delhi’s former chief minister, Arvind Kejriwal, said the BJP had falsely reported thousands of voters as dead or as having either relocated to different addresses.

Citing the Shahdara constituency as a specific example, he had claimed that BJP workers led by Vishal Bhardwaj, a media co-ordinator for the party in the seat, had signed 11,018 Form 7 applications to delete voters' names in this constituency. Kejriwal claimed that an examination of 500 randomly selected deletions had shown that 70% of the deleted voters were alive and resident in Shahdara, and were therefore eligible to vote.

After the Delhi results were announced, no one asked the obvious question that if the AAP lost 10% of the total vote, amounting to a fifth of its entire support base, had all of these votes gone only to the BJP? Did none of them come to the Congress?

A more detailed analysis of the suspected electoral malpractice in the Delhi Vidhan Sabha elections was given by Sanjay Singh, a key organiser of the AAP, who had spent six months in jail on unproven charges of having made money in the so-called “liquor policy scam” before the Supreme Court ordered his release, noting that no illegal funds had been recovered from him.

On Kapil Sibal’s programme Central Hall, Singh gave a detailed account of the number of deletion applications that purported BJP affiliates had filed in at least 12 constituencies, before Sibal stopped him.

Janakpuri: 6,247

Sangam Vihar: 5,862

R.K. Puram: 4,285

Palam: 4,031

Dwarka: 4,013

Tughlaqabad: 3,987

Okhla: 3,933

Karawal Nagar: 2,957

Lakshmi Nagar: 2,147

In Shahdara, Singh confirmed that a single BJP karyakarta (party worker), possibly the same Vishal Bhardwaj, had asked for 11,008 deletions.

At Rajouri Garden, a middle-class neighbourhood in Delhi, six BJP workers had applied for 571 deletions.

At Hari Nagar, four party workers had applied for the deletion of 637 voters from the electoral rolls.

These add up to 49,678 voter deletion applications.

If similar applications had taken place in all constituencies, it would mean that close to 2.9 lakh voters may have been at risk of being disenfranchised. That amounts to 3% of all the votes cast in the election.

It is against this mounting evidence of irregularities in the voting process that Gandhi voicing his suspicion that the EC had helped the BJP steal the Mahadevapura assembly in Karnataka constituency has struck a body blow to the credibility of the commission created under the Modi government’s Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Term of Office) Act of December 2023.

The change that has taken place in the EC’s behaviour after the resignation of CEC Arun Goel on March 9, 2024, just days before the announcement of dates for the last general election, has been dramatic.

The change is best depicted by contrasting it with the state CEC’s behaviour in a similar, Form 7-based voter deletion attempt in Andhra Pradesh in 2019. In 15 days before the Vidhan Sabha election, over eight lakh Form 7s meant to delete voters from electoral rolls were submitted online, many of them by the YSR Congress led by Jagan Mohan Reddy.

The office of Gopal Krishna Dwiwedi, who was election commissioner for Andhra Pradesh, sent officials door to door to have these verified, and then approached the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing, which operates under the Union government’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, for the IP addresses of the computers from where the forms were submitted in bulk.

The verification process found that 95% of the 5.5 lakh deletions that had been examined were without basis and that there were only 30,000-40,000 bogus voters. The Form 7 deletions had been sent by the YSR Congress allegedly to reduce the vote share of the Telugu Desam Party.

It is against this background of the pre-2023 EC's irreproachable handling of an earlier attempt to use Form 7 to gerrymander an election, that we need to assess the present commission’s reaction to the Congress party’s exhaustive analysis of Mahadevapura, a single assembly segment of the Bangalore Central parliamentary constituency in Karnataka.

Listening to Gandhi’s press conference on the details of voting in Mahadevapura, the question that sprang immediately to my mind was, ‘Why did he choose only a single assembly segment? Why not the entire parliamentary constituency, or better still, the entire parliamentary election vote in Karnataka?’

Gandhi had anticipated this question, and the answer he gave was chilling. First, the EC had refused point blank to give the electronic voting data to the Congress even though it could have been supplied within minutes, and is the right of every citizen of a democracy to ask for. Had it done so, the Congress would have been able to analyse the voters’ lists not just in Mahadevapura, but throughout the Bangalore Central parliamentary constituency in a matter of hours.

Instead, all that the EC was prepared to release were the paper copies.

When these arrived in the office of the Congress party, they turned out to be a 20-foot-high pile of forms delivered in three six-and-seven-foot stacks. When the Congress tried to scan these with an OCI reader, it found that the paper on which these had been printed was unscannable.

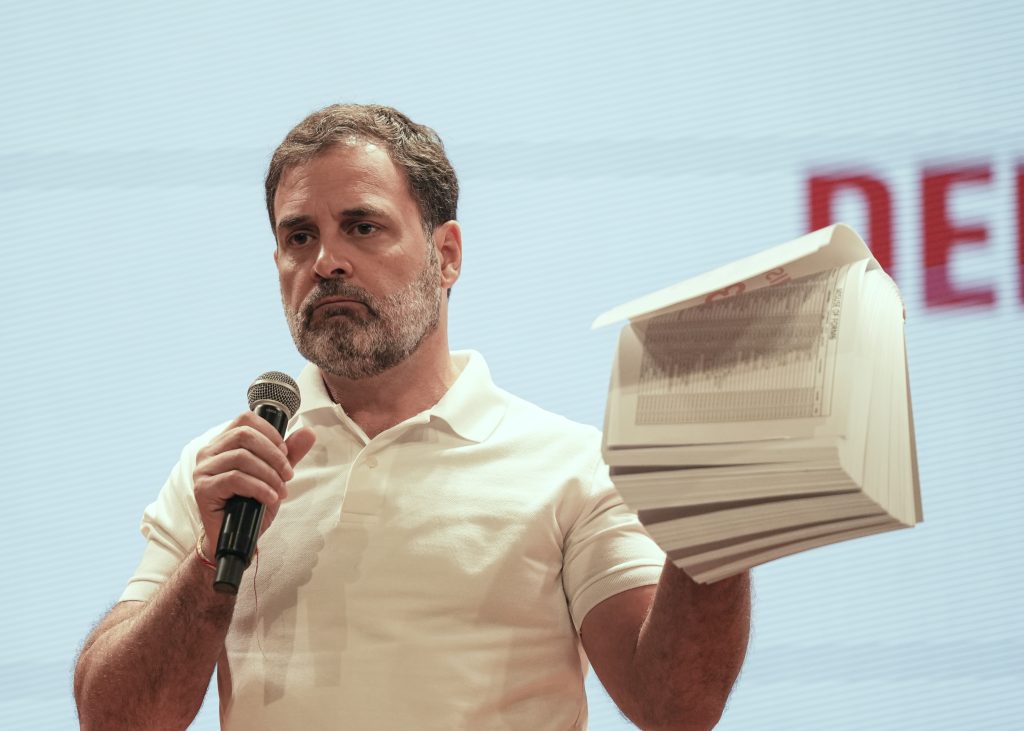

The results that Gandhi presented in his press conference come on top of the alleged gerrymandering of the Maharashtra and Delhi elections described above. Photo: PTI/Salman Ali.

Anyone who has worked with computers knows that even texts published 60 years ago (this writer’s articles of the 1960s, for example) can be scanned by OCI readers. So it would require a special kind of paper to make sure that what is printed on it cannot be scanned. The EC had therefore taken the trouble to find and store this type of paper.

When the Mahadevapura results were delivered, the Congress found itself confronted by voter lists with six-and-a-half lakh names. The task it faced was to compare each voter name, address and photograph with every other name on the list to spot any irregularities that might exist. This mammoth task took 30-40 people six months to complete. That is why Gandhi was able to release their findings only this month.

By now these have been seen or read by so many people that his allegations are on the way to becoming a part of the folklore of the country. Very briefly, 1,00,250 names out of the six-and-a-half lakh names on the Mahadevapura voter list were fake. It is not known if all of the 1,00,250 fake voters voted. If they did, they would make up 28% out of the total votes cast, which was 3,54,830.

Of the 1,00,250 fake voters, 11,965 were duplicate names; 40,009 voters had given fake or invalid addresses; 10,452 voters had given addresses at which there were up to 80 persons supposedly living in a single room; 33,962 voters had been added to the voters’ list through the misuse of Form 6; and 4,132 had missing or invalid photographs.

Coming on top of the alleged gerrymandering of the Maharashtra and Delhi elections described above, the results that Gandhi presented in his televised press conference raise the suspicion that the BJP is determined to use the EC to capture a sufficient number of state assemblies in the coming four years to ensure that it will also win the Lok Sabha elections in 2029.

How does it intend to do this? Ironically, part of the answer was given by one of its own appointees. When election commissioner Arun Goel suddenly resigned a few months after parliament had passed the Election Commission selection Bill, it became apparent that, to quote Hamlet, “Something was rotten in the Kingdom of Denmark.”

Goel’s replacement, Rajiv Kumar, said in his final press conference: ‘There are 1.05 million (10.5 lakh) polling booths in the country. Each has to be manned by four or five officials. In all, between four and five million persons are needed [for a nationwide election]. These four to five million polling officials are from their respective states, from different departments and have different skill sets (italics added).’

‘From their respective states’. That is wherein the rub lies. For, state government officials follow the instructions of their superiors. In BJP-ruled states, and those where the BJP is likely to come to power, booth-level officers (BLOs) can therefore be more or less relied upon to follow the instructions, or indications, given by their superiors.

This is not mere speculation. When elections were held in Kashmir after nine years of insurgency in 1996, and the National Conference won by a large majority, most Kashmiris were sure that the elections had been rigged. This had caused widespread disaffection, and a resumption of the militancy, albeit on a somewhat reduced scale.

But when the same fear was again expressed by a majority of the Kashmiris in the run-up to the 2002 elections, the chief election commissioner at the time was James Michael Lyngdoh, who hailed from the Northeast and was made from a different mettle.

Lyngdoh first decided to appoint all BLOs from among state government officials recruited in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. But when chief minister Farooq Abdullah protested bitterly, he relented and reduced the number of out-of-state BLOs. Honour was satisfied, the people’s distrust allayed and the election was won by the Congress and the newly formed People’s Democratic Party with a landslide.

Rajiv Kumar, who was the first chief election commissioner appointed by the Modi government under the new law, never even mentioned this simple remedy.

Meanwhile, when Gandhi gave the details of the alleged theft of votes in Mahadevapura, his successor Gyanesh Kumar has demanded that he swear an oath or give an affidavit, before the commission takes cognisance of his allegations. He made this demand knowing that were Gandhi not able to prove it upon being challenged in court, he could be fined, or sent to jail for up to three years under section 229 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita.

When the Congress and the INDIA bloc demanded access to the CCTV footage from polling booths in Maharashtra to check whether there had indeed been a huge rush to vote after 5 pm in the evening as the BJP had claimed, the EC not only refused but has also gone on to announce that all the CCTV footage will be destroyed in 45 days. No one inside or outside the Modi government was bothered by the fact that this would be a crime against history.

In Mahadevapura, when the Congress demanded access to the electronic voting record, the EC refused point blank, saying that it would violate a suddenly discovered “voters’ privacy”. Instead, it agreed to provide the printed voters’ papers. But it only provided this on paper that could not be electronically read.

The EC in deciding to delete CCTV footage of an election within 45 days claimed it was to prevent the spread of misinformation by non-contestants, but it clearly did not occur to a government that claims to represent 4,000 years of Hindu civilisation that this would destroy the possibility of future research by scholars and activists on the nature of elections in the world’s largest Hindu-majority democracy.

In the face of the torrent of suspicion and distrust that the EC's reactions have provoked, it is essential to ask why its responses have been solely those of aggression. Is it not meant to serve the people rather than ride roughshod over them? And should Indians, in particular members of parliament who are their elected representatives, not have the right to question the findings and decisions of administrative bodies that have been created to serve them?

All things considered, this aggressive reaction reeks of guilt. So it has not explained why a special intensive revision (SIR) of the electoral rolls in Bihar was ordered only five months before the Vidhan Sabha election in that state, when in 2003, the SIR for Bihar was conducted two years before the Vidhan Sabha election and a full year before the 2004 Lok Sabha elections.

The number of electors in Bihar has risen from 49.6 million in 2003 to 78.9 million today. The EC has said that all those who were voters in 2003 only need to furnish an excerpt of their name in that year's roll to prove their eligibility, but this will still leave millions of voters to be freshly registered within a single month.

The only beacon of light in this gathering, all-enveloping gloom is the Supreme Court’s order that those struck off the draft rolls can submit their Aadhaar card while petitioning for re-inclusion into it. Had this not been mandated by the court, it is not hard to surmise which segments of the people could have lost their vote.

These would have been the poorest of the poor, who cannot produce even birth certificates, and migrant workers. Even today, the youngest eligible voters have a birth registration rate of 26.2%. As for migrant workers, the EC has chosen the precise month – July – when their employment, whether in farmers’ fields or on construction sites, is at its peak.

Had the Supreme Court not stepped in, lakhs of voters could have been one step closer to losing their right to vote. It is not difficult to surmise which political party would have suffered the most. The answer is obvious: it would have been Tejashwi Yadav’s Rashtriya Janata Dal.

But Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United) would not have escaped unscathed either. Nitish Kumar is too seasoned a politician not to have realised this. So perhaps the time has come for the Grand Alliance to reach out to him once more.

Prem Shankar Jha is a veteran journalist and commentator.

This article was updated to reflect Sanjay Singh's figures more accurately.

This article went live on August twenty-ninth, two thousand twenty five, at twenty minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.