Election Commission Appointments: It’s Time to Go Back to the Future

In its 73-year journey as a constitutionally mandated body in charge of conducting elections to Parliament, state assemblies, and the position of president and vice-president, the Election Commission of India (ECI) has had its ups and downs.

As the chief election commissioner (CEC) and two election commissioners (EC) have traditionally been appointed by the president acting on the advice of the council of ministers – effectively by the union government, or the executive – the core concern regarding the Election Commission’s performance has always been that of its independence – how independent is it to conduct free and fair elections, a crucial aspect of a functioning and resilient democracy. What impact if any does a government with a brute majority in parliament have on the independent working of the institution?

This question, which has resounded across the country’s political landscape in the last several years, creating a sense of disquiet, has gathered storm in the past six months. After all, there is a line-up of state assembly elections before the nation goes to the polls in 2024.

First, on March 2, 2023, in Anoop Baranwal vs Union of India, the Supreme Court directed that the appointments of the CEC and the ECs “shall be done by the President of India on the basis of the advice tendered by a Committee consisting of the Prime Minister of India, the Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha and, in case, there is no such Leader, the Leader of the largest Party in the Opposition in the Lok Sabha having the largest numerical strength, and the Chief Justice of India. This norm will continue to hold good till a law is made by the Parliament.”

On August 10, 2023, the Modi government introduced The Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Terms of Office) Bill, 2023, in the Rajya Sabha, saying, among other things, that “The Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners shall be appointed by the President on the recommendation of a Selection Committee consisting of— (a) the Prime Minister—Chairperson; (b) the Leader of Opposition in the House of the People—Member; (c) a Union Cabinet Minister to be nominated by the Prime Minister—Member.”

This sequence of events has fuelled an animated debate among legal scholars, former CECs, civil servants and civil society organisations in the public media.

While a clear, unambiguous assessment of the Bill in the context of the judgment would help foreground the nuances of the issue at stake, the fact is that appointments to the ECI are so crucial that we need to look beyond the Supreme Court judgment and the Bill for a fresh perspective.

The Central Wing of the Supreme Court of India, where the Chief Justice's courtroom is situated. Photo: Subhashish Panigrahi/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Supreme Court judgment

Judgments of the higher judiciary typically comprise several major segments. They begin with what can broadly be referred to as the facts of the case – the historical or contextual background, a summary of relevant laws including those presented by the opposing counsel.

Then come the critical components, sometimes partly overlapping with the facts of the case, namely, the direction(s) and the ratio decidendi (the legal principle or rationale for the decision), which are essential. (The other component, obiter dicta, or that which is said in passing by the judge, is not essential to the ruling.)

The rationale of the Supreme Court’s ruling, reproduced above, is excerpted from para 125 of Justice Ajay Rastogi’s concurring judgment:

"Keeping in view the importance of maintaining the neutrality and independence of the office of the Election Commission to hold free and fair election which is a sine qua non for upholding the democracy as enshrined in our Constitution, it becomes imperative to shield the appointment of Election Commissioners and to be insulated from the executive interference…."

In the main judgment, Justice K.M. Joseph, speaking for himself, Justice Aniruddha Bose, Justice Hrishikesh Roy, and Justice C.T. Ravikumar, writes a separate section titled ‘Independence: a sterling and indispensable attribute.’ This section, which forms the crux of the rationale for the entire judgment, deserves to be quoted at some length:

"What is independence? Independence is a value, which is only one of the elements in the amalgam of virtues that a person should possess. The competence of a man is not to be conflated with fierce independence. A person may be excellent, i.e., at his chosen vocation. He may be an excellent Administrator. He may be honest but the quality of independence transcends the contours of the qualities of professional excellence, as also the dictates of honesty. We may, no doubt, clarify that, ordinarily, honesty would embrace the quality of courage of conviction, flowing from the perception of what is right and what is wrong. Irrespective of consequences to the individual, an honest person would, ordinarily, unrelentingly take on the high and mighty and persevere in the righteous path. An Election Commissioner is answerable to the Nation. The people of the country look forward to him so that democracy is always preserved and fostered.[…] Independence must be related, finally, to the question of ‘what is right and what is wrong’. A person, who is weak kneed before the powers that be, cannot be appointed as an Election Commissioner. A person, who is in a state of obligation or feels indebted to the one who appointed him, fails the nation and can have no place in the conduct of elections, forming the very foundation of the democracy. An independent person cannot be biased. Holding the scales evenly, even in the stormiest of times, not being servile to the powerful, but coming to the rescue of the weak and the wronged, who are otherwise in the right, would qualify as true independence. Upholding the constitutional values, which are, in fact, a part of the Basic Structure, and which includes, democracy, the Rule of Law, the Right to Equality, secularism and the purity of elections... would, indeed, proclaim the presence of independence. Independence must embrace the ability to be firm, even as against the highest. Not unnaturally, uncompromising fearlessness will mark an independent person from those who put all they hold dear before their Karma.…

It is important that the appointment must not be overshadowed by even a perception, that a ‘yes man’ will decide the fate of democracy and all that it promises (emphasis added)."

The essence of the rationale for the decision of this judgment, therefore is independence of Election Commissioners and their insulation from executive interference. Independence, in this context, “must embrace the ability to be firm, even as [sic] against the highest”.

Watch: 'Modi Govt's EC Bill Undermines Its Independence, Should Be Struck Down if Passed'

How far does the Bill follow the rationale of SC ruling?

A quick look at the table below is sufficient to show the extent to which The Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Terms of Office) Bill, 2023, follows the rationale anchoring the Supreme Court ruling.

| Section No. | Description | Supports independence | Reduces independence |

| 5 | Only current and former secretaries to the Government of India, who are persons of integrity, who have knowledge of and experience in management and conduct of elections, can be appointed as ECs or CEC. |

| X |

| 6 | Search Committee consisting of Cabinet Secretary and two other Secretaries to the Government of India shall prepare a panel of five persons for consideration of the Selection Committee, for appointment as CEC and ECs. | X | |

| 7 (1) | Selection Committee will consist of— (a) Prime Minister; (b) the Leader of Opposition in Lok Sabha; and (c) a Union Cabinet Minister to be nominated by the PM. | X | |

| 7(2) | Appointment of CEC and other ECs shall not be invalid merely by reason of any vacancy in or any defect in the constitution of the Selection Committee. | X | |

| 8(2) | The Selection Committee may also consider any other person than those included in the panel by the Search Committee. | X | |

| 9(2) | The CEC and ECs shall not be eligible for re-appointment. | X | |

| 9(3) | Where an EC is appointed as CEC, his term of office shall not be more than six years in aggregate as the EC and CEC | X | |

| 10(1) | The salary, allowances and other conditions of service of the CEC and other ECs shall be the same as those of the Cabinet Secretary: | X | |

| 10(5) | Where the CEC or an EC had retired from the service of the Central Govt or a State Govt prior to appointment as such, the aggregate period for which the encashment of unutilised earned leave he shall be entitled to, shall be subject to a maximum period as admissible to the Cabinet Secretary. | X | |

| 11(2) | The CEC and ECs shall not be removed except in accordance with the provisions contained in the first and second provisos respectively of clause (5) of article 324 of the Constitution. | X | |

| 15 | Save as otherwise provided in this Act, the conditions of service relating to travelling allowance, medical facilities, leave travel concession, conveyance facilities, and such other conditions of service as are, for the time being, applicable to the Cabinet Secretary, shall be applicable to the CEC and ECs. | X | |

| 2 | 9 |

As can be seen, only two sections are likely to support the ECI’s independence whereas nine will work towards reducing it. The remaining sections are of a general nature which do not have any implications for the institution’s independence, or lack of it.

Clearly, while the Bill observes the letter of the SC judgment by way of making a law, it overwhelmingly, if not completely, violates the spirit or the rationale for the judgment. As the court observes in para 227 of its judgment:

"…it was intended all throughout that appointment exclusively by the Executive was to be a mere transient or stop gap arrangement and it was to be replaced by a law made by the Parliament taking away the exclusive power of the Executive. This conclusion is clear and inevitable…"

Barriers to the exercise of independence by the ECI

By providing for three levels of barriers in the Bill, the government has tried its best to ensure that the Election Commission is not able to function independently under any circumstances:

- Eligibility criteria for EC and CEC appointments (Section 5 of the Bill): Only current and former secretaries to the Government of India (GoI), that is, only those who have been part of the executive for long are to be considered for these positions. How independent can such persons be of the executive is a matter of opinion.

- Procedure for shortlisting candidates (Section 6 of the Bill): It will be a case of bureaucrats choosing bureaucrats – the search committee comprising the cabinet secretary and two other secretaries to the GoI, will shortlist as EC and CEC hopefuls, persons who have been diehard members of the executive for years.

- The composition of the selection committee (Section 7(1) of the Bill): Whereas the Supreme Court judgment had suggested a committee comprising the prime minister, leader of the opposition, and the chief justice of India, the Bill replaces the non-executive element of the chief justice of India with “a Union Cabinet Minister to be nominated by the PM.” With two of the three members of the selection committee hailing from the executive, how can anyone even dream of an Election Commission acting independent of the executive!

Also read: ‘Umpire Cannot be Subordinate to Team Captain’: Election Commissioners Bill Raises Questions

Seeing the judgment and the Bill in a larger context

It must be said unambiguously that while the Supreme Court judgment of March 02, 2023, was a distinct step forward for protecting democracy in the country, the proposed Bill takes two steps backward in that process.

One also needs to point out that the Supreme Court’s decision regarding the composition of the selection committee was possibly influenced, at least to some extent, by the prayers in the petitions before the court. [Disclosure: an organisation that this writer is associated with, Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), was one of the petitioners in the case before the Supreme Court].

The experience of appointments by similar collegiums or committees – of the director, Central Bureau of Investigation, central information commissioners and chief information commissioner, among others – broadly shows that this method has not always resulted in the best possible or the most appropriate recommendations. Maybe there is a need to break new ground on this aspect.

One’s suggestion regarding the need to break new ground is not meant to distract attention from the current task of opposing the passage of the Bill in both houses of Parliament. It goes without saying that the Bill is damaging to democracy and must be opposed at all costs.

Why breaking new ground is necessary

The criticality of the position of the ECI, the CEC and ECs in a democracy demonstrates the urgency for a new perspective on the issue. The criticality of the institution is clearly stated early on in the SC judgment (para 41):

"The Chief Election Commissioner and Election Commissioners stand on a far higher pedestal in the constitutional scheme of things having regard to the relationship between their powers, functions and duties and the upholding of the democratic way of life of the nation, the upkeep of Rule of Law and the very immutable infusion of life into the grand guarantee of equality under Article 14 (emphasis added)."

In a similar vein, the SC judgment also describes the uniqueness of Article 324 of the Indian Constitution which provides for the establishment of the ECI (para 219):

"However, it is equally clear that Article 324 has a unique background. The Founding Fathers clearly contemplated a law by Parliament and did not intend the executive exclusively calling the shots in the matter of appointments to the Election Commission (emphasis added)."

The proposed Bill has been made in pursuance of Article 324(2) of the Constitution which says, among other things, that “the appointment of the Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners shall, subject to the provisions of any law made in that behalf by Parliament, be made by the President”.

It is in this context that the court examines Article 324(2) in depth in a section of the judgment titled ‘Articles in the Constitution, which employ the words “subject to any law” to be made by Parliament as contained in Article 324.’ This examination in the judgment, from para 34 to para 49, ends with the observation, “No further discussion is needed to conclude that Article 324(2) is unique in its setting and purpose (emphasis added)”.

Stressing the importance of the ECs’ role, the court observes:

"We have already elaborated and found that core values of the Constitution, including democracy, and Rule of Law, are being undermined. It is also intricately interlinked with the transgression of Articles 14 and 19. Each time, on account of a ‘knave’, in the words of Dr. Ambedkar, or again in his words, ‘a person under the thumb of the Executive’, calls the shots in the matter of holding the elections, which constitutes the very heart of democracy, even formal democracy, which is indispensable for a Body Polity to answer the description of the word ‘democracy’…” (Para 226).

The SC contrasts ECI’s uniqueness in contrast to that of the comptroller and auditor general of India while comparing Articles 324 (2) and 148:

"On a comparison of both the Articles, the difference is stark and would justify the petitioners’ contention that in regard to the appointment of the Members of the Election Commission, having regard to the overwhelming importance and the nearly infinite plenary powers [,] they have in regard to the most important aspect of democracy itself, viz., the holding of free and fair elections …” (para 228).

The court finally concludes, “In the unique nature of the provision [Article 324 (2)] we are concerned with and the devastating effect of continuing to leave appointments in sole hands of the Executive on fundamental values, as also the Fundamental Rights… (emphasis added).”

It is these very pointers by the Supreme Court regarding the need to keep alive ECI’s uniqueness that have prompted one to think of a new perspective on the issue, of breaking new ground.

The “not so” new ground for a fresh perspective

However, it may surprise many that what one is referring to as ‘new’ ground was actually explored by Constituent Assembly member, Professor Shibban Lal Saxena, who moved an amendment to a proposal made by Dr B.R. Ambedkar. The significance of the amendment is such that it deserves to be quoted extensively:

"Mr. President, Sir, I must congratulate Dr. Ambedkar on moving his amendment. As he has said, his amendment really carries out the recommendations of the Fundamental Rights Committee and in fact the matter was so important that it was thought at one time that it should be included in the Fundamental Rights. The real purpose is that the fundamental right of adult franchise should not only be guaranteed in practice. He has explained to us that he has tried to make the Election Commission wholly independent of the Executive and he therefore hopes that by this method the fundamental right to franchise of all the individuals shall not only be guaranteed but that it shall also be exercised in a proper manner so that the elected People will represent the true will of the people of the country. After a careful study of his amendment I have suggested my above amendments to carry out the real purpose of Dr. Ambedkar’s amendment in full.

What is desired by my amendment is that the Election Commission shall be completely independent of the Executive. Of course it shall be completely independent of the provincial Executive but if the President is to appoint this Commission, naturally it means that the Prime Minister appoints this Commission. He will appoint the other Election Commissioners on his recommendations. Now this does not ensure their independence. Of course once he is appointed he shall not be removable except by 2/3rd majority of both the Houses. That is certainly something which can instil independence in him, but it is quite possible that some party in power who wants to win the next election may appoint a staunch party-man as the Chief Election Commissioner. He is removable only by 2/3rd majority of both Houses on grave charges, which means that he is almost irremovable. So what I want is this that even the person who is appointed originally should be such that he should be enjoying the confidence of all parties--his appointment should be confirmed not only by majority but by two-thirds majority of both the Houses. If it is only a bare majority then the party in power could vote confidence in him but when I want 2/3rd majority then it means that the other parties must also concur in the appointment so that in order that real independence of the commission may be guaranteed, in order that everyone even in Opposition may not have anything to say against the Commission, the appointments of the Commissioners and the Chief Election Commissioner must be by the President but the names proposed by him should be such as command the confidence of two-thirds majority of both the Houses of Legislatures. Then no person can come in who is a staunch party-man. He will necessarily have to be a man who will enjoy the confidence of not only one party but also of the majority of the members of the Legislature. Then alone he can get a 2/3rd majority in support of his appointments. I therefore, think that if the real purpose of the recommendations of the Fundamental Rights Committee is to be carried out, as Dr. Ambedkar proposes to do this by amendment, then he must provide that the appointment shall […] be by the president subject to confirmation by a two-thirds majority of both the Houses of Parliament sitting and voting in a joint session. […]

I want that in future, no Prime Minister may abuse this right, and for this I want to provide that there should be two-thirds majority which should approve the nomination by the President. Of course there is danger where one party is in huge majority. As I said just now it is quite possible that if our Prime Minister wants, he can have a man of his own party, but I am sure he will not do it. Still if he does appoint a party-man and the appointment comes up for confirmation in a joint session, even a small opposition or even a few independent members can down the Prime Minister before the bar of public opinion in the world. Because we are in a majority we can have anything passed only theoretically. So the need for confirmation will invariably ensure a proper choice. Therefore, I hope this majority will not be used in a manner which is against the interests of the nation or which goes against the impartiality and independence of the Election Commission. I want that there should be provision in the Constitution so that even in the future if some Prime Minister tends to be partial, he should not be able to be so. Therefore, I want to provide that whenever such appointment is made, the person appointed should not be a nominee of the President but should enjoy the confidence of two-thirds majority of both the Houses of Parliament."

The Supreme Court judgment also quotes the Constituent Assembly member’s amendment with approval and notes that the amendment was not accepted because of opposition from some other members. The result was the existing Article 324(2) saying that the President will appoint the CEC and ECs “subject to the provisions of any law made in that behalf by Parliament.” The kind of Bill that has been introduced is proof of Constituent Assembly member Saxena’s foresight!

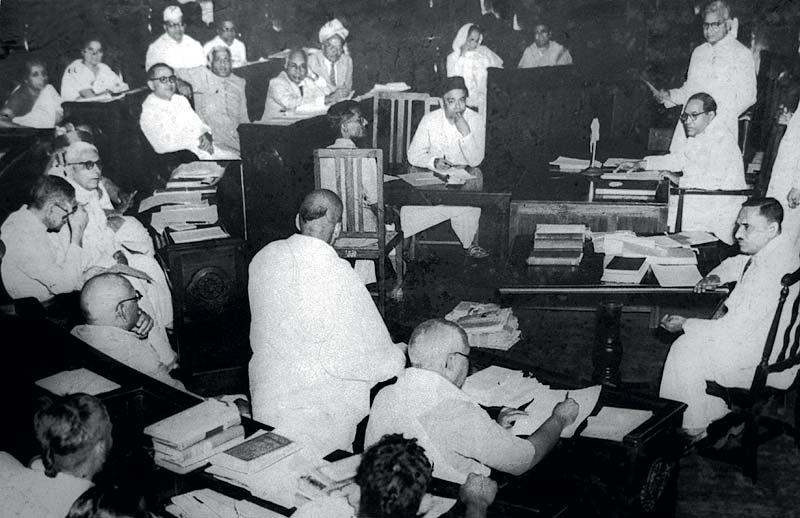

A Constituent Assembly of India meeting in 1950. B.R. Ambedkar can be seen seated top-right. Photo: Unknown author, Public Domain,

A citizen’s proposal for EC and CEC appointments

Following Constituent Assembly member Saxena’s lead, here is a proposal for a procedure to appoint the CEC and ECs:

1. An existing committee of parliament or a new committee formed for this purpose to propose the eligibility criteria for appointment as EC/CEC.

2. The committee’s proposals would then be placed before parliament, requiring approval by two-thirds majority of the members of parliament present and voting.

3. Once the eligibility criteria are approved by parliament, the same committee should be entrusted with the task of searching for and selecting individuals for the position of ECs/CEC.

3.1 The committee should invite nominations of and applications by individuals considered appropriate for and interested in being appointed as ECs/CEC.

3.2 Out of the nominations and applications received, the suitable candidates should be shortlisted by the committee.

3.3 The interviews of short-listed aspirants by the committee should be conducted in open hearings, accessible for viewing by the general public through video-transmission.

3.4 After the hearings, the committee should select individuals proposed to be appointed as ECs/CEC.

4. The next stage would be for the committee to send its recommendations to parliament for consideration.

5. The committee’s recommendation should be considered approved by parliament only if approved by two-thirds of the members of parliament present and voting

6. Once approved by parliament, the recommendations should be sent to the President for assenting to the appointments.

7. Once appointed, such persons should occupy their positions for six years or the age of 75 years whichever is earlier. Persons above the age of 69 years should not be appointed so that each appointee has a tenure of six years.

8. The stipulations of point 7 should apply to each appointment independently. Every EC should have a tenure of six years and every CEC should have a tenure of six years.

Critics might say that the proposed system will be very time consuming and may even term it impractical. This may well be true, given the way parliament functions, or does not function, these days. But if India has to move towards a really functional and substantive democracy, parliament and parliamentarians have to learn to be responsible.

This is the only option if the uniqueness of the Election Commission and its critical role in sustaining democracy is recognised and accepted.

Jagdeep S. Chhokar is a concerned citizen.

This article went live on September first, two thousand twenty three, at thirty minutes past one in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.