A Missed Shot: What Explains India’s Delay in the HPV Vaccine Rollout?

New Delhi: In her interim budget speech in February 2024, Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced that the government would encourage vaccination for girls for the prevention of cervical cancer. Prime Minister Narendra Modi reiterated the commitment in an interaction with Bill Gates in March 2024. However, more than a year later, India remains among the 46 countries that have still not introduced cervical cancer vaccine in their routine immunisation programme.

According to data from Global Cancer Observatory, India reported 1,27,526 new cervical cancer cases and 79,906 deaths in 2022, accounting for ~19% of cervical cancer cases detected and ~23% cervical cancer deaths globally. Approximately 60% of Indians die following a cancer diagnosis, with cancer related mortalities in women rising faster compared to men.

Cervical cancer is highly preventable, with its cause well understood

Infection with the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus (HPV) is the major cause for 95% of cervical cancer. 80%-90% women develop an HPV infection during their lifetime. While 90% of these infections and associated low grade lesions clear out by themselves, persistent, unresolved HPV infection causes cervical cancer. It takes 20-40 years for an HPV infection to cause cervical cancer, according to the WHO.

A combination of two preventive strategies are required to eliminate cervical cancer: vaccinating girls aged 9-14 years, before exposure to HPV; and regular HPV-based screening in women above the age of 25-35 (in India, cervical cancer screening is recommended for women above 30 years of age every five years).

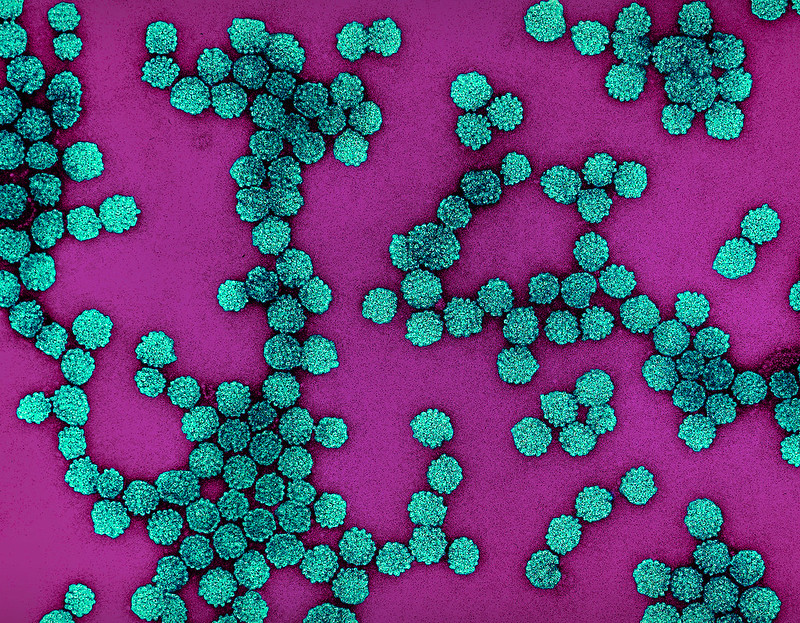

Colorized electron micrograph of HPV virus particles (teal) harvested and purified from cell culture supernatant. Captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Photo: NIAID/Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

HPV vaccines are highly effective (close to 100%) in preventing HPV vaccine type-related persistent infection. Evidence from the administration of the vaccines in 125 countries in the last two decades has demonstrated their safety.

Screening infrastructure in India is severely lacking; only 1.9% of Indian women (aged 30–49 years) have ever undergone cervical cancer screening.

HPV vaccine uptake in India is very low

HPV vaccines have been available in India since 2008. Currently, three vaccines are available in the market: Gardasil 4 and Gardasil 9 by Merck Sharpe & Dohme (MSD), and Cervavac by Serum Institute of India (SII). Gardasil 4 costs Rs 4,000 per dose, Gardasil 9 sells for nearly Rs 11,000 while Cervavac costs Rs 2,000 per dose. WHO recommends a single or two dose schedule for girls and young women aged 9-20 years.

Vaccines are made available to the government at considerable discounts to the market price; MSD reportedly sells its HPV vaccine to state governments for around Rs 350 per dose, and SII plans to provide Cervavac at "substantially, probably eight times, cheaper" price to the government.

“While there is no data for HPV vaccine coverage in India, it is very low. This is due to unaffordable prices of the vaccines and lack of awareness among people. Further, given that HPV is acquired sexually, there is a misconception among some parents that the vaccines might encourage young kids to get sexually active,” said a vaccine industry executive who did not wish to be named.

Top immunisation body endorsed HPV vaccines, yet no clarity on government’s plan

In June 2022, the National Technical Advisory Group for Immunisation (NTAGI) recommended the introduction of HPV vaccines in India’s Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP), with initial vaccination of girls aged 9-14 years, followed by routine immunization of 9 year old girls. NTAGI is the highest advisory body on immunisation in India and consists of independent experts who review data on disease burden, efficacy and cost effectiveness of vaccines to provide their recommendations for introduction of new vaccines in the UIP.

UIP provides free immunisation against 12 diseases to women and children in the country. The programme covers around 2.67 crore newborns and 2.9 crore pregnant women annually.

Nearly 3 years after NTAGI’s second recommendation, the government is yet to provide details regarding HPV vaccine rollout under UIP. Despite Sitharaman’s announcement in February 2024, no budgetary allocation was made for the initiative even in subsequent budgets announced in July 2024 and February 2025.

In January 2025, Union health secretary Punya Salila Srivastava said that the ministry was “strategising” on rolling out HPV vaccines in a “few months’ time”. Despite multiple calls and emails from The Wire, Srivastava and other senior health ministry officials did not respond to queries regarding steps taken by the government to include HPV vaccines in the UIP. This story will be updated if a response is received.

According to Fauzia Khan, a Rajya Sabha member from the Nationalist Congress Party and a former Minister for Health and Women & Child Development in the Maharashtra government, “It’s quite common to find big announcements being made in the budget, without any concrete allocation towards those issues. The unfortunate reality is that elections and political issues take centrestage even there.”

Vaccine supply critical for successful rollout

“Cervical cancer was identified as a public health problem, however, there were constraints related to adequate supply of vaccines and high costs. Also, under UIP, India has so far prioritised childhood vaccines. It is only recently that the conversation is moving towards a life-course programme, where adolescents and adults are also taken into account,” explained Dr Raj Shankar Ghosh, a veteran physician who is part of the Cervical Cancer Elimination Consortium-India, an initiative of public health experts and Indian and global health agencies focused on eradicating cervical cancer.

Speaking to The Wire, Dr. N.K. Arora, who was the chairperson of NTAGI’s HPV Working Group, said, “We had recommended the inclusion of these vaccines in the UIP even in 2017. Shortage of vaccines in the global market was a key constraint at that time. The recommendation was made again in 2022 in view of the impending approval for SII’s HPV vaccine. India would require 7.5 crore HPV vaccines when it starts the programme. Thereafter, the vaccine supply needs to be ensured for 1.3 crore 9-year-old girls for each subsequent year.”

After receiving market authorisation from Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI) in July 2022, Cervavac, India’s first indigenously developed vaccine against cervical cancer was commercially launched by Home Minister Amit Shah in January 2023.

Experts say India has the capacity to produce such vaccines at scale, partly due to infrastructure developed for Covishield production by SII, which received significant government support. With a capacity to produce 300 crore doses of all types of vaccines each year, SII is the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer. According to the vaccine industry executive that The Wire spoke to, SII’s current production of Cervavac is very low, largely due to lack of demand. However, they expected the capacity to increase to 7 crore doses of Cervavac by the end of 2025.

Given the lack of awareness about the vaccines and prohibitive pricing, large scale demand is only expected to come from the government through UIP.

“The government is expected to launch a tender for procurement of HPV vaccines by the end of this year,” said the vaccine industry executive. Similar reports of a likely tender had also surfaced in 2023 and 2024 as well.

“The government will not take a firm decision on rollout unless it receives a commitment for adequate supply from Merck and SII. My understanding is that SII has indicated its readiness to make such a commitment, so rollout should happen very soon," Ghosh, quoted earlier in this sub-section, said.

According to Ghosh, India has one of the best cold chain infrastructure for vaccines, leaving only the issue of training healthcare professionals and identifying centres for administration of the vaccine to be figured out. “These would not require a lot of time though,” he said.

India’s budgetary allocation for healthcare is abysmal; preventive healthcare is even more neglected

The government allocated nearly Rs 96,000 crore to the healthcare sector for FY26, 9.5% higher than previous year. The FY24 healthcare expenditure was 1.9% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), much lower than the 2.5% of GDP recommended under the 2017 National Health Policy, and far lower than the 5.4% spent by low and middle income countries.

India also does not prioritise preventive healthcare in its budget. As per the National Health Account Estimates for FY22, only 14% of healthcare budget is allocated towards preventive measures such as health screenings, immunisation programmes and public health education.

Despite shortcomings, UIP has succeeded in vaccinating large numbers of target population

To arguments claiming that the government may not be showing urgency on HPV vaccines given limited funds and the fact that any roll out would only reduce cancer incidence and mortality after a couple of decades, Arora said, “Since 2015, India has introduced seven vaccines under the UIP. Our country already has a massive infrastructure in place to ensure that vaccines reach the last person in the target population.”

India has a successful record of vaccination under the UIP. As of FY2023-24, 93.23% of eligible children have received full immunisation. India recorded its last polio case in 2011 and successfully eliminated maternal and neonatal tetanus in 2015.

“I believe that HPV vaccination is a matter of will. During the pandemic, India demonstrated the will to ensure that the population is adequately vaccinated against COVID, and was able to do so,” said MP Khan. Although not covered under UIP, India had administered 220 crore doses of COVID-19 vaccine by February 2023.

States in India take the lead, but only Sikkim maintains momentum

In 2016, Delhi began providing the bivalent vaccine to girls aged 11-13 years. Around 13,000 girls received the vaccine from 2016-2020. In 2017, Punjab began a limited drive for administering HPV vaccines, which was later discontinued. A study published in 2017 found that immunising 11-year-old girls for cervical cancer in Punjab would cost 0.028% of the state’s health budget, after considering the treatment costs for cervical cancer.

In 2018, Sikkim became the first state to introduce HPV vaccines as part of routine immunisation through schools across the state. According to Dr. Arora, Sikkim has continued its programme and covers around 80-90% eligible girls every year. NTAGI’s HPV Work Group attributed Sikkim’s success to strong political will, involving senior doctors in media discussions around the campaign, engaging parents through parent-teacher meetings and assigning one teacher as nodal person for HPV vaccination. Most recently, the Tamil Nadu government announced that it would provide human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines to all girls aged 14 and above, earmarking Rs 36 crore in the FY25-26 budget.

However, most states, including NDA ruled Andhra Pradesh, are waiting for the Union government's push through UIP to start government sponsored HPV vaccination.

In India’s neighbourhood, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka have introduced HPV vaccines in their national immunisation programmes. While India’s HPV vaccine rollout remains in limbo, millions of girls in the country remain at risk of developing cervical cancer.

Shania Ali is an independent journalist based in Delhi.

This article went live on April fourteenth, two thousand twenty five, at thirty minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.