No SIR, Women and Migrants Have a Right to Vote

As Babasaheb Ambedkar observed, in India’s parliamentary democracy, “‘one [wo]man, one vote; one vote, one value’ is our political maxim”, but the contradiction is that while we have “in politics, equality; in economics inequality” thrives, leading to “fabulous wealth and abject poverty”.

In this scenario of extreme inequality, Mahatma Gandhi had a talisman for public service: “Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest [wo]man whom you may have seen, and ask yourself, if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to [her]him.”

Will the poorest Bihari voters benefit in any way from the special intensive revision (SIR)? Or do they stand to lose their legitimate citizenship, all social security benefits and perhaps even liberty?

More than 1,00,000 people in Assam have been categorised as 'D-voters' till date under suspicion of being undocumented Bangladeshis, with thousands languishing in detention centres. In Bihar’s first draft electoral roll released on August 1 itself, the Election Commission (EC) has erased more than 6.5 million voter names, equivalent to the population size of Serbia.

Even Rashtriya Janata Dal leader Tejashwi Yadav apparently made a mistake by claiming that his name was not on the list. This faux pas indicates the confusion among voters and the quality of the draft list, and how farcical it is to conduct an SIR in 60 days. In his latest press conference he has also said that more than three lakh households on the voter list have ‘0’ as their house number. So why is the EC in such a hurry?

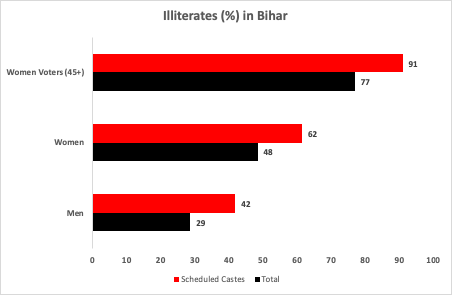

Chart via author. Source: 2011 Census.

Bihar is a state where virtually half the women are illiterate (48%) as per the 2011 census. Amongst women above 45 years, 77% cannot read a form. Amongst Dalits in this age group, the figure is 91%.

Now all Bihari voters, even if semi-literate, are supposed to search for their names on this new draft list. If their names are missing, then the burden is on them to submit two forms along with documentary proof before September 1.

Scroll has confirmed that 55% of those summarily excluded from the draft roll are women, despite the century-long international suffragette movement to ensure women earned the right to vote. Preliminary analysis by The Hindu also indicates higher voter deletions in Muslim-majority districts and those with high out-migration.

Bihar also has amongst the largest proportion of internal migrants. 3.5 million of those deleted have apparently either permanently migrated or could not be traced. So a population the size of Mongolia which was allowed to vote in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections has now been summarily expunged.

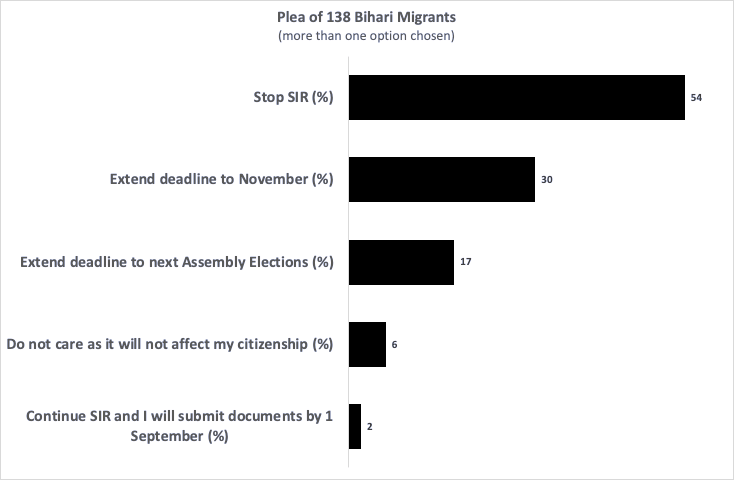

So, 138 Bihari migrants living in Bengaluru, Delhi, Bhilwara and Balotra have submitted individual statements to the Supreme Court to highlight their plight. In distant lands, away from their homes battling hunger, slave wages and inhumane living conditions, more than half who have submitted these testimonies with the support of civil society collectives had not even heard of the SIR before we informed them. Sameer Khan summarised their plight aptly as, “mazdooron ko kuchh malum nahi hai (labourers know nothing).”

Let us consider three scenarios. First, if any of these migrants are deleted from the draft rolls as untraceable (we spoke to them before August 1), few would have any idea as most had left their voter cards in their villages and thus cannot enter their voter ID into the EC's website to know their status. Even if they were aware, around a third did not have any of the 11 documents required by the EC to be re-included in the list.

In contrast, 99% said they had an Aadhaar card, 89% a bank passbook, 80% a PAN card and 70% a ration card. These findings are similar to the phone survey by the Stranded Workers Action Network. Despite the Supreme Court’s order on July 10, the EC in its counter affidavit has made no commitment to including the easily available Aadhaar, voter or ration cards. This begs the question raised by the SC – is this an exercise designed for mass inclusion or exclusion?

Second, even if the EC were to expand the list of eligible documents, only 11% of migrants had been able to submit their forms online, let alone upload documents. As Surendra Mahto in Bengaluru said, “form bharne ki jaankari nahi hai (we don’t have information on how to fill the form).”

The average cost of returning home to Bihar was around Rs 4,500 across the four cities, a quarter of their monthly wages. Most complained that they could not go back.

Guddu Kumar in the Rajasthani city of Bhilwara, for example, stated, “main factory me do saal se kaam karta hu aur gareeb ghar ka eklauta kamane wala hu (I have been working in the factory for the past two years and I am the only breadwinner for my poor family).”

Sahil Mohammed, who works in a hotel, also complained, “chhutti nahi hai, malik nikal denge (I don’t get leave; my employer will fire me).”

Anita Devi, who does housekeeping work for a private company, echoed, “chhutti nahi milti, bachhe ke saath jaane mein taklif hoti hai (It is hard to get leave, it is tough to travel [back to Bihar] with children.

Chart via author.

Lastly, what if they are declared dead? How will they go to the courts to prove that they are “alive” and “citizens”? The EC in its latest affidavit has even refused to publish the list of deleted persons and the reasons why they were not included in the draft rolls.

Most of these migrants survive on meagre wages and face substantial discrimination. Their average monthly income is merely Rs 16,182.

Most labourers we met in Bengaluru were living in squalid conditions, with seven to ten migrants housed in a room, sharing mattresses by work shifts. Many Biharis work at the Krishnarajendra Market that was once a historic battlefield and some also moonlight as delivery agents for mobile apps to save some money to send back home. Now, most of these hard-working souls would not even be aware if their names have been struck off voter rolls.

As per Yogendra Yadav and Rahul Shastri’s calculations based on population estimates, this may be the largest voter disenfranchisement in the world in the 21st century.

The cancer of SIR also threatens to spread. The EC has apparently already started meetings for the rollout of an SIR in Manipur and possibly in Delhi and West Bengal. For the last two years Manipur has been simmering with ethnic strife with more than 50,000 people in refugee camps. Even as the government plans to shut down all refugee camps by December, is the cleaning of electoral rolls the most important priority?

As Bihari migrant Santosh Kumar, who works in a factory in Rajasthan’s Bhilwara, pleaded, “SIR … ise turant roka jaye (please stop this SIR immediately).”

Will Indian electoral democracy survive, SIR?

I am grateful to various civil society collectives in four cities and Utkarsh Singh, Pratishtha Choudhary, Shuchi Gupta and Palakh Saldhi as research volunteers.

Swati Narayan is faculty at the National Law School of India University in Bengaluru.

This article went live on August twelfth, two thousand twenty five, at forty-five minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.