Senthil Balaji Case: SC Verdict Cements ED's 'Illegibility' in Law, its Power to Take Custody

The Supreme Court has recently delivered its judgement in V. Senthil Balaji v. State case, deciding two crucial issues connected with Section 167 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) – first, whether the Enforcement Directorate (ED) is entitled to obtain an accused’s custody thereunder; and second, in case it is, whether such custody can be obtained when the first 15 days after arrest have elapsed. The court answered both questions in the affirmative, conferring upon the ED the power to obtain an accused’s custody despite its officers not constituting the police, and holding that the requirement of the first 15 days was so inextricably tied up with the facts in CBI v. Anupam Kulkarni that it didn’t constitute a general binding rule.

In this piece, I discuss the court’s treatment of the issue of the ED’s power to obtain custody, proposing that the instant case has the effect of further constituting the ED as an entity highly illegible in law, which can conveniently shapeshift into different avatars based on the greatest rights-restrictive interpretation of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA).

Also read: How the Enforcement Directorate Has Become an Excessive Directorate

I make this argument in the following manner – first, I discuss the groundwork upon which the court was to decide the instant case, which concerned the binary of police and judicial custody, along with the ED’s divergence therewith; and second, based on this groundwork, I discuss the ED’s powers to obtain an accused’s custody, arguing that the unreasoned pursuit of an omnipotent ED is all that stands as reasoning.

Entrenched binaries and institutions beyond binaries

The powers of the ED to effect arrest are provided under Section 19 of the PMLA, which requires superior ED officials to have a "reason to believe" in a person’s guilt. Pursuant to Section 19(3) of the PMLA, all persons arrested must be presented before a judicial magistrate within 24 hours. The trajectory of events after the accused’s production before the magistrate, therefore, is in question.

“Custody” – as explained in Gautam Navlakha v. NIA – is the period for which the accused is present either exclusively with the police to allow them to undertake “custodial interrogation” or in a jail, where the police are ordinarily forbidden from entering and interrogating. This binary of police and judicial custody necessitates all forms of custody to fall under either two categories. As a corollary, it forbids custody to an entity not constituting either the court or the police, which is commonsensically derivable from the text of Section 167(2) and is fairly entrenched in case law.

The text of Section 167(2) equips the magistrate to detain an accused in “such custody as he thinks fit”, while the first proviso thereto states that only custody “otherwise than in custody of the police” may exceed 15 days. The term “otherwise than in the custody of the police”, it must be noted, can only mean judicial custody, for there is no actor other than the police or the court that can obtain the accused’s custody. This proposition can be verified both from the design of other laws that forego this twisted terminology, as well as case law that attempts to fit all kinds of custody of the accused within these two categories.

The Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002, for example, contained Section 49(2)(b) that amended Section 167(2) of the CrPC for offences committed under the former, creating a regime for shifting an accused to “police custody from judicial custody”. This amendment was upheld by the Supreme Court in Maulavi Hussein Haji Abraham Umarji v. State of Gujarat, with the court noting that “the acceptance of application for police custody when an accused is in judicial custody is not a matter of course” [25]. A similar regime of shifting custody is provided u/s 43D(2)(b) of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, which again creates a regime for shifting custody, noting the existence only of police and judicial custody –

“Provided…that if the police officer making the investigation…requests, for the purposes of investigation, for police custody from judicial custody of any person in judicial custody, he shall file an affidavit…”

Further, proviso (b) to Section 167(2) expressly notes the binary of police and judicial custody, forbidding the magistrate from approving police custody for an accused who wasn’t physically produced before them. Even in Gautam Navlakha, it must be noted that the issue solely concerned the characterisation of house arrest as either police or judicial custody – for only such characterisation would have the effect of making the accused eligible to obtain default bail under Section 167(2) [107].

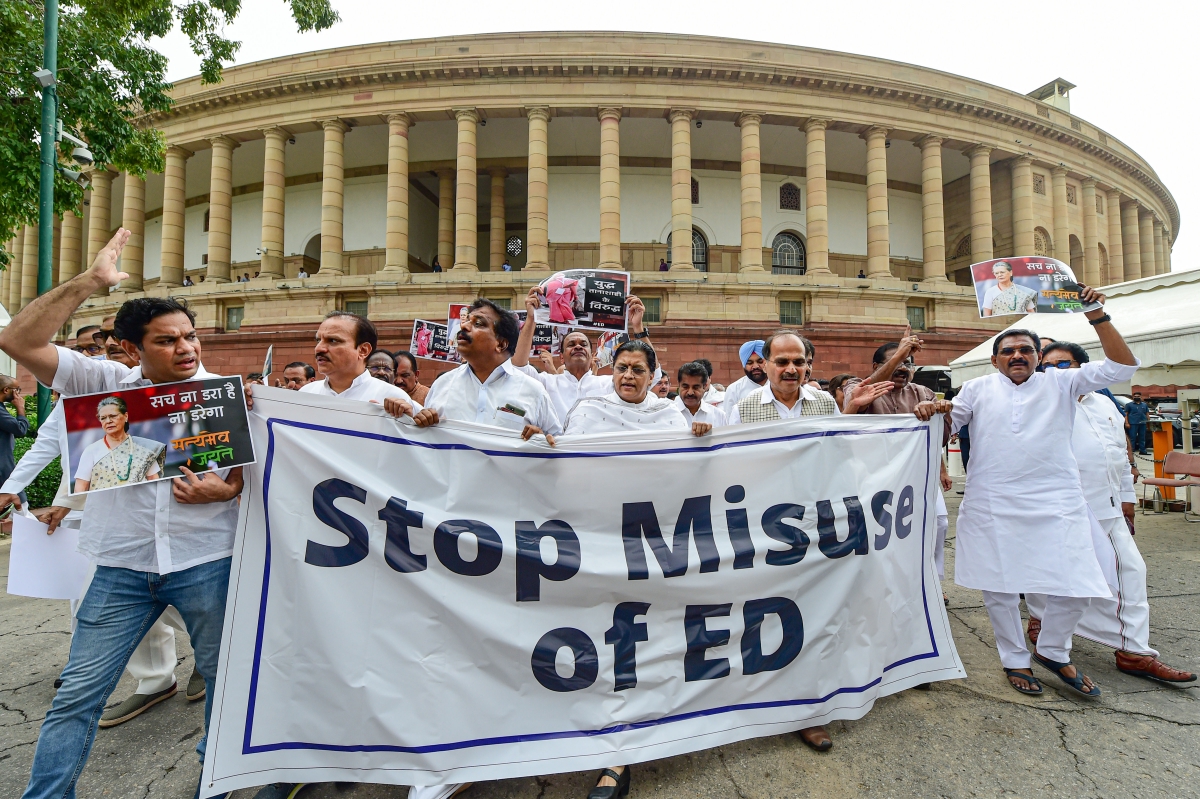

Congress MPs holding banner and placards stage a protest march at Parliament House complex to express their solidarity with the party Chief Sonia Gandhi who has to appear before the Enforcement Directorate in connection with the National Herald case, in New Delhi, July 21, 2022. Photo: PTI/Kamal Kishore

It is clear, therefore, that the provisos to Section 167(2) envision only “police custody”, and “custody otherwise in the custody of the police” (interpreted as judicial custody), forbidding the magistrate from authorising the alternative forms of custody of the accused, with entities that aren’t the police or the court. On this basis, in case the ED seeks to obtain the accused’s custody, it must demonstrate its character either as the police or as a court.

Here lies the problem – the Supreme Court in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary vs Union of India, in order to bolster the strength of the ED to obtain confessions and make them relevant under Section 25 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (IEA) – specifically held that “it is unfathomable as to how the authorities [of the ED]…can be described as police officer”, relying on unsatisfactory case law whose standards require an identity of functions between the impugned agency and the police for the former to qualify as such [438].

The court also upheld the constitutionality of Section 50 of the PMLA that confers upon the ED judicial powers of examining witnesses, with lying to the ED punishable with up to seven years in prison under Section 193 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. On this basis, the court noted that the ED dons a judicial hat at the summoning stage u/s 50. At the same time, however, the court held that if a confession was obtained post-arrest, the judicial hat is lost, and the confession again becomes irrelevant under Section 25 of the IEA, observing the following –

431. “…However, if his/her statement is recorded after a formal arrest by the ED official, the consequences of Article 20(3) or Section 25 of the Evidence Act may come into play to urge that the same being in the nature of confession, shall not be proved against him.”

Since Section 25 of the IEA expressly uses the term “police officer” to negate the relevance of confessions, the only way in which a confession can be irrelevant post-arrest is if the entity obtaining it becomes a police officer. The court held, effectively, that the ED loses its judicial hat after it arrests, now becoming the police. While this observation doesn’t sit well with the court’s holding that the ED generally doesn’t constitute the police, an alternative construction attracting the applicability of Section 25 is unlikely. On this basis, the ED is a court for summoning purposes, the police for arresting purposes – and yet, isn’t really the police.

Escaping Binaries – Senthil Balaji on ED custody

The above was the groundwork for the court to navigate in Senthil Balaji, implying that it could either have held that the ED, not being the police generally, could not obtain custody for the purposes of interrogation, or it could employ Choudhary’s observations on the post-arrest (police) character of the ED, making it eligible to obtain custody.

The Supreme Court – along with two judges of the Madras high court – chose neither, instead holding that Section 167(2) doesn’t create a binary between police and judicial custody at all. The court held – interpreting Section 167(2) divorced from provisos (a), (b) and (c) – that the presence of the words “such custody” therein obviates the requirement of the custody-obtaining entity being the police –

85. “One shall not confuse such powers conferred under the statute with the police power, however, when it comes to application of Section 167(2) of the CrPC, 1973 such an authority has to be brought under the expression “such custody” especially when the words “police custody” are consciously omitted. Therefore, the ratio laid down in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary (supra) has to be understood contextually, in its own perspective.”

The words “police custody” and “judicial custody”, as Abhinav has noted, though absent from the body of Section 167(2), are present under both provisos. The structure of Section 167(2) is such that the provisos become determinative of the kinds of custody that can be allowed – this is because while the body empowers the Magistrate to allow “such custody as he thinks fit”, proviso (a) states that he can allow custody without the police beyond fifteen days, meaning that he can allow custody with the police only for fifteen days. As discussed above, proviso (b) states that while police custody can only be authorized only through the accused’s physical production in court, judicial custody can be authorized through the accused’s online production, and proviso (c) states that no second-class Magistrate can authorize police custody. It is clearly discernible that Section 167(2) is wholly premised on the distinction between police and judicial custody, and does not envision custody beyond these categories.

Balaji, the accused under Section 4 of the PMLA, made another argument on the basis of the scheme of the PMLA and CrPC before the Madras HC – he argued that the threshold of arrest u/s 19 of the PMLA is that of a “reason to believe” accused’s guilt, and the ED can obtain such reasons only through the interrogation it undertakes at the summoning stage u/s 50. Pursuant to Choudhary (and contrary to Nandini Satpathy v. P.L. Dani), the individual summoned before the ED u/s 50 doesn’t enjoy a right to remain silent, and a refusal to cooperate through uttering false information constitutes an independent offence. On this basis, Balaji argued that if one has already undergone interrogation where one was legally bound to tell the truth, and based on such interrogation (and other investigation), the ED had “reasons to believe” that he was guilty, what purpose could be served by further custodial interrogation through post-arrest ED custody?

The tie-breaker judgement of the Madras HC, however, repelled this contention, holding that there was “one small fallacy in the…argument” [136], which is the following –

145. “Once it is stated that the Code of Criminal Procedure applies, then these persons, namely, the Director, the Deputy Director, the Assistant Director, who are not police officials can take advantage of every provision under the Code of Criminal Procedure to obtain, in their opinion a logical conclusion to the trial process. If that step requires further investigation then they have every right to seek custody.”

This “fallacy”, according to the Madras HC, is that even though the ED has all possible resources to definitively pinpoint one’s guilt before effecting arrest, they should still be able to seek custody, because it is their right. This reference to a fallacy, it is submitted, points to no fallacy at all, for the only justification the Court finds for repelling this argument is an unreasoned pursuit of an omnipotent ED.

Conclusion

The instant case, therefore, has the effect of further entrenching the ED’s illegibility, which – when seen with Choudhary – creates an entity with the following characteristics:

- The ED is generally not the police (Choudhary, [438]).

- The ED is a court for the purposes of summons under Section 50 of the PMLA and can compel one to answer its questions, and can prosecute one for perjury for lying to it. (Choudhary, [431])

- The ED can, during the stage of summons, extract confessions from an accused, which would be relevant under Section 25 of the IEA. This is because of (1) – the fact that the ED is not the police.

- The ED can validly effect arrest under Section 19 of the PMLA when it has “reason to believe” that a person is guilty of an offence under the PMLA (Choudhary, [322]).

- After the ED arrests, Section 25 of the IEA somehow becomes applicable, though the ED still isn’t the police (Choudhary, [431]).

- Despite the occurrence of the substantial interrogation in (2) that would have created the “reason to believe” in (4), and the post-arrest “police” character of the ED in (5), the ED still isn’t the police (Balaji [84]), but is entitled to custody u/s 167(2) (Balaji [85]).

This state of affairs, to say the least, is highly incoherent and unprincipled – Choudhary was premised on strengthening the ED to the greatest possible extent, creating an entity that is deliberately illegible in law, with the court sitting comfortably with its shapeshifting character. The instant case builds on this illegibility – entrenching it deeper instead of attempting to escape it.

Kartik Kalra is a student at the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru.

This article went live on August twenty-ninth, two thousand twenty three, at fourteen minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.