Fact Check: Old Data, New Spin in PM-EAC Report on India’s Population

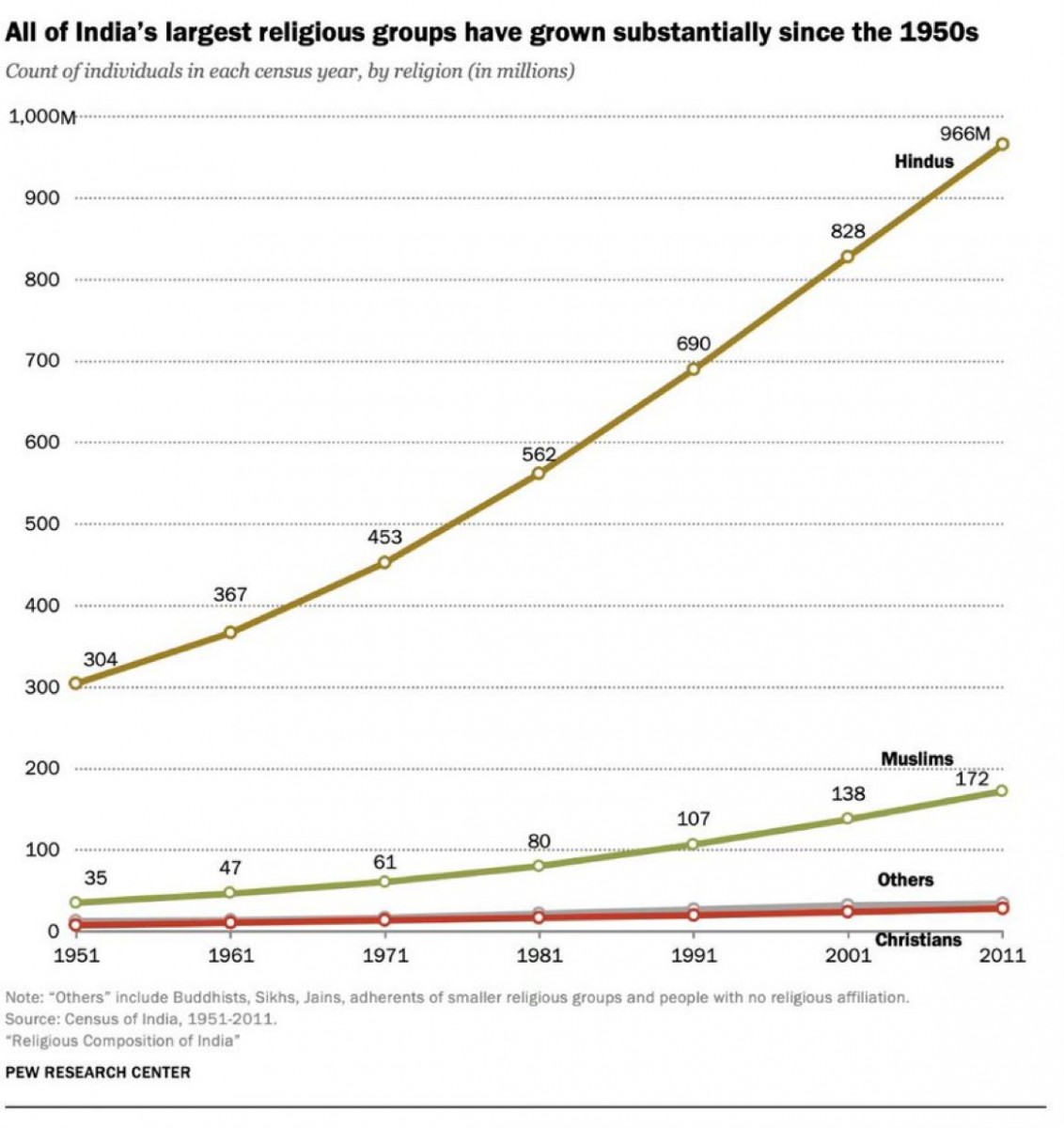

New Delhi: A report from the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (PM-EAC)– using old data, but with a new spin – has made headlines. The so-called revelation from this paper is that the share of minorities in India’s population increased between 1950 and 2015, while the share of Hindu population dipped. What this report did not seek to highlight, however, is that populations of all religious groups in India are continuing to grow from 1950-2011.

Source: Pew Research

The timing of this report – bang in the middle of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, during which the Bharatiya Janata Party has run an openly anti-Muslim campaign and engaged in scare-mongering – raises serious questions. Then the way it is being cited in sections of the media appears to be yet another attempt to further the BJP’s false narrative. Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself, at a political rally last month, referred to Muslims as “those who have more children” – and so take away a chunk of India's resources. He was repeating a slur BJP leaders have used before. Earlier, at least one BJP member of parliament introduced a private member's bill demanding a law to 'control' population growth.

There is evidence that if anything, population growth/stabilisation is directly linked to women’s literacy, empowerment, child mortality levels and other socio-economic variables. If the PM-EAC was to look at the same (i.e. old Census) data it is citing, through the lens used by serious demographers, it will find that both ‘Hindus’ and ‘Muslim’ rates of growth are much higher in north India, as opposed to south India. But the choice of the ‘religion-axis’ for reheated material served up just now is not surprising.

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman had talked about constituting a committee on this in her interim budget speech this year – the budget she presented on the eve of election. That speech was perhaps a harbinger of how population growth would become a centre point of discussion during the election.

She had said:

"The Government will form a high-powered committee for an extensive consideration of the challenges arising from fast population growth and demographic changes. The committee will be mandated to make recommendations for addressing these challenges comprehensively in relation to the goal of ‘Viksit Bharat’."

This statement in her speech did not make a reference to any particular religion but the opposition, perhaps because of the BJP’s track record, had interpreted it as a statement targeting minorities.

However, in making this statement, the finance minister contradicted what her own ministry had said in the Economic Survey 2018-19, which she herself tabled in Parliament.

The Economic Survey had said:

"India is set to witness a sharp slowdown in population growth in the next two decades."

"[The] population projection at the national and State level upto 2041 show that India has entered the next stage of demographic transition, with population growth set to slow sharply in the next two decades."

So while the Economic Survey presented in 2019 said there was a sharp slowdown in population growth, her budget speech in 2024 said the population has been rising at a fast pace. There is absolutely no demographic data available to say that the slowdown in the Indian population growth rate reversed between 2019 and 2024.

The Economic Survey presented in 2019 also didn't present any concern on Muslims being outliers in the declining trend of population growth. However, Shamika Ravi, a member of the PM-EAC, and other authors of the paper released on May 7 titled 'Share of Religious Minorities: A Cross-Country Analysis (1950-2015)' have sought to indicate this concern in the paper; Ravi has also repeated it in her commentary to the media.

This was quickly picked up by some media outlets which reported the claims verbatim. The Population Foundation of India has termed the reporting misleading and alarmist. “The media's selective portrayal of data to highlight the increase in the Muslim population is an example of misrepresentation that ignores broader demographic trends,” said Poonam Muttreja, Executive Director, Population Foundation of India.

“According to the Census of India, the decadal growth rate for Muslims has been declining over the past three decades. Specifically, the decadal growth rate for Muslims decreased from 32.9% in 1981-1991 to 24.6% in 2001-2011. This decline is more pronounced than that of Hindus, whose growth rate fell from 22.7% to 16.8% over the same period. The census data is available from 1951 to 2011 and is quite similar to the data in this study, indicating that these numbers are not new,” the Foundation’s statement continued.

Facts on ‘Muslim’ rates of growth

BJP leaders like Modi are not just discriminatory when they single out one community – Muslims – and hold them responsible for India’s population growth; they are also unscientific and wrong. All analysis suggests that the total fertility rate or TFR among Muslims, as across other religions, has declined in the past few decades.

Former head of Mumbai-based International Institute of Population Sciences and noted demographer K.S. James wrote in a piece back in 2021 saying that across all religions in India, Muslims had registered maximum population growth between census periods of 1951-61 and 2001-2011. However, the Muslim population growth rate reduced by seven percentage points while the Hindu rate had dropped by three percentage points only.

It must be clarified that Muslims traditionally had a higher TFR as compared to other religious groups. Therefore, the baseline, from which the decline has to be measured is higher. So, any decline in TFR of Muslims would naturally be higher in quantum than any other group as they had a bigger scope of decline. But this does not take away the fact that PM Modi's description of Muslims bearing unusually high numbers of children was misleading.

An analysis done by 'Ideas For India' last year had also found that the gap between TFR among Hindus and Muslims has only reduced over time – thereby meaning that the difference in the number of children born to the people of different religious groups has become nearly minimal.

In the light of these facts, how should one make sense of Modi's and his partymen's statement?

"Political leaders are parochial…this narrative suits them. The hype around the issue gives them a visibility [of being concerned about population growth]," N. Bhaskara Rao told The Wire. Rao was the member of MS Swaminathan Committee on Population Control. The Commission submitted its report in 1994.

India’s population trajectory not surprising

India has not conducted a census since 2011, but other reliable global surveys suggest that it has recently overtaken China, and is now the most populous country in the world. However, given demographic trends in India and China over time, there have been surprises when the world learnt this.

What has simultaneously happened is that India has achieved 'replacement levels' of population growth. If a woman gives birth to 2.1 children, on an average,it is called 'replacement fertility rate'. A country achieving a replacement level fertility rate is a milestone in the story of stabilising population growth.

The number of children that a woman gives birth to is called total fertility rate or TFR. India's current TFR, according to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-5, is 2.0. This makes India go slightly under the replacement levels required as per replacement fertility rates.

Replying to a question from CPI(M) MP John Brittas in the Rajya Sabha on July 19, 2022, minister of state for health Bharti Pravin Pawar had claimed that the Union government had succeeded in achieving population control.

"[The] efforts of the government have been successful in reining in the growth of population," she said, referring to the current TFR, replacement level fertility rate, contraceptive usage going up and crude birth rate declining.

Not once has any parliamentary reply in the last ten years, on population growth, identified Muslims as being the “problem”.

The world has also taken note of India's declining TFR.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) said in November 2022, "The good news is that India’s population growth appears to be stabilising…A total of 31 States and Union Territories (constituting 69.7% of the country’s population) have achieved fertility rates below the replacement level of 2.1."

An article published in March this year in The Lancet said India's TFR is going to decline further. It may reach 1.75 by 2027.

BJP’s politics, never mind the facts

It seems like the BJP government wants to have its cake and eat it too.

While one minister celebrates success in population control, others claim that the 'rising' population is a cause of concern – in an attempt to further their polarising politics.

Previously, BJP MP Rakesh Sinha presented a private member's bill titled 'Population Regulation Bill, 2019, in the Rajya Sabha. The Bill called for penal action against people who have more than two children, withdrawal of social and financial benefits from them, and debarring them from applying for government jobs or contesting elections.

A reference note on population control by the reference division of the parliamentary library states Sinha withdrew the Bill on the insistence of BJP's Mansukh Mandaviya – also the Union health minister.

"The criticism of the bill states that it will widen the gap between the poor and the rich," the note states. "The poor will suffer if benefits under public distribution schemes or other government-funded schemes are taken away from them," it added.

Uttar Pradesh chief minister Adityanath's office released a press statement on July 11, 2021 – World Population Day – saying that increasing population was the root cause of many problems in the society.

This statement had come on the heels of the UP's state law commission releasing a draft copy of Uttar Pradesh Population (Control, Stabilisation and Welfare) Bill the same year. It was open for public comments till July 19 – for eight days after the chief minister’s office's statement came out on the 'evils of population growth’.

That Bill, just like BJP MP Sinha's Bill, also said that people having more than two children would not be allowed to contest local body elections. It said the government's social and financial benefits, including the ration supplied through the public distribution system, would be restricted for people not following the two-child norm.

The Uttar Pradesh Bill also put the onus on women, saying their sterilisation was the best possible means to control the population. This, when there is more than enough data to suggest that the burden of having less children has disproportionately fallen on women.

Even though the BJP's politicians have been toying with the idea of a legal instrument to tackle the issue of population growth the past few years, the Modi-led Union government has been saying in parliamentary replies on several occasions that it was not in favour of any population control bill, The Wire's analysis of all such answers given in the last ten years reveal.

All those answers, in fact, lauded the efforts of the Modi government in bringing down the fertility rates without singling out any religious group – a success that the BJP leaders not don't seem to claim in their political speeches.

Thought currently BJP ally and Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar has said on several occasions that educating girls is the best way to stabilise the population. He has often repeated this claim, but he only drew sneers and insults from the BJP when he did it last in the Vidhan Sabha. Nitish was with the Mahagathbandhan at the time.

Interestingly, the union finance minister's interim budget speech and other BJP leaders have referred to ‘fast population growth', even though India’s seminal data collection exercise, the Census, has been delayed for at least three years now – making it impossible to get a completely accurate picture.

This is the first time in the history of the country that the Census has been delayed without citing a cause after the pandemic. Citizens have also not been told when it will be conducted.

"Without a census, the finance minister's statement was one in the blind and merely a political one," Rao said.

Rhetoric apart, where’s the policy?

The population of China, after increasing for several decades, has started declining – a trend that will eventually be true about India as well.

But before the India population starts declining, which is not expected until 2067 as the above chart shows, India is going to face major policy challenges on various fronts. India will be a nation of young people.

"There are so many Indians in this age group that roughly one-in-five people globally who are under the age of 25 live in India," said research by the Pew Research Center.

Its research also said people under the age of 25 account for more than 40% of India’s population.

"A high-powered committee, if at all needed now, is to visualise how the young people are going to get jobs and how we are going to provide education to children and the younger generation," Rao said.

Rao is not the only one to worry about this. Even the Economic Survey 2018-19, referred to above, had expressed these concerns.

The Economic Survey had said, "Depending upon the trajectory of labour force participation during 2021-41, additional jobs will need to be created to keep pace with the projected annual increase in working age population."

It had projected that the working population will grow roughly from 9.7 million per year during 2021-31 to 4.2 million per year from 2031-41.

With unemployment rates soaring sky-high currently, according to recent reports from the International Labour Organisation and several others, it is difficult to imagine how India as a nation will be able to provide jobs to the humongous population.

Worse, several reports, even the government's own studies, like the India Skills Report 2021, suggest that nearly half of India’s graduates, currently, are unemployable. During the ongoing election campaign, opposition parties have raised the unemployment issue time after time – and the Modi regime has failed to come up with constructive solutions.

The other big challenge is related to providing secondary education and higher education, especially higher education. According to the government's own latest estimates, the gross enrolment ratio (percentage) is a little more than 50% and for higher education (18-23 years) is merely 27.3%.

Healthcare is going to be a significant challenge also to deal with in both the scenarios – before and after the population starts declining.

"If India’s hospital facilities remain at current level, the rising population over the next two decades despite the slowdown in population growth rate will sharply reduce per capita availability of hospital beds," the Economic Survey had warned.

Once the population of India starts declining after the 2060s, India will be a country of elderly people – something that China and Japan are experiencing now. There would have to be a special policy in place for the care of the ageing population.

India has already lost momentum in reaping benefits from the ‘demographic dividend’ which it should have done, recognising its people as its strength. Now, blinded by its ideological predilections of ‘Muslim growth rates’ and in ignoring facts, not gathering enough data and taking a scientific view of it and therefore not preparing for the future – an ageing population – it may be getting ready to miss another bus.

This article went live on May tenth, two thousand twenty four, at twelve minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.