Maiden Pharma, the Company Whose Syrup Killed Gambian Children, Is a Habitual Offender

New Delhi: Maiden Pharmaceuticals Ltd., the Haryana-based company that manufactured and exported the cough syrup that took the lives of 66 children in the Gambia, is a repeat offender and has also lied about being WHO-certified on its website, The Wire has learnt.

Twenty-four hours ago, the WHO issued an alert against four products made by Maiden because they contained diethylene glycol and ethylene glycol. The metabolism of these two compounds in the human body leads to significant liver and kidney damage.

This is why the US has a tight limit of just 0.2% of diethylene glycol in polyethylene glycol when polyethylene glycol is used as a food additive. Maiden’s cough syrups themselves required polyethylene glycol.

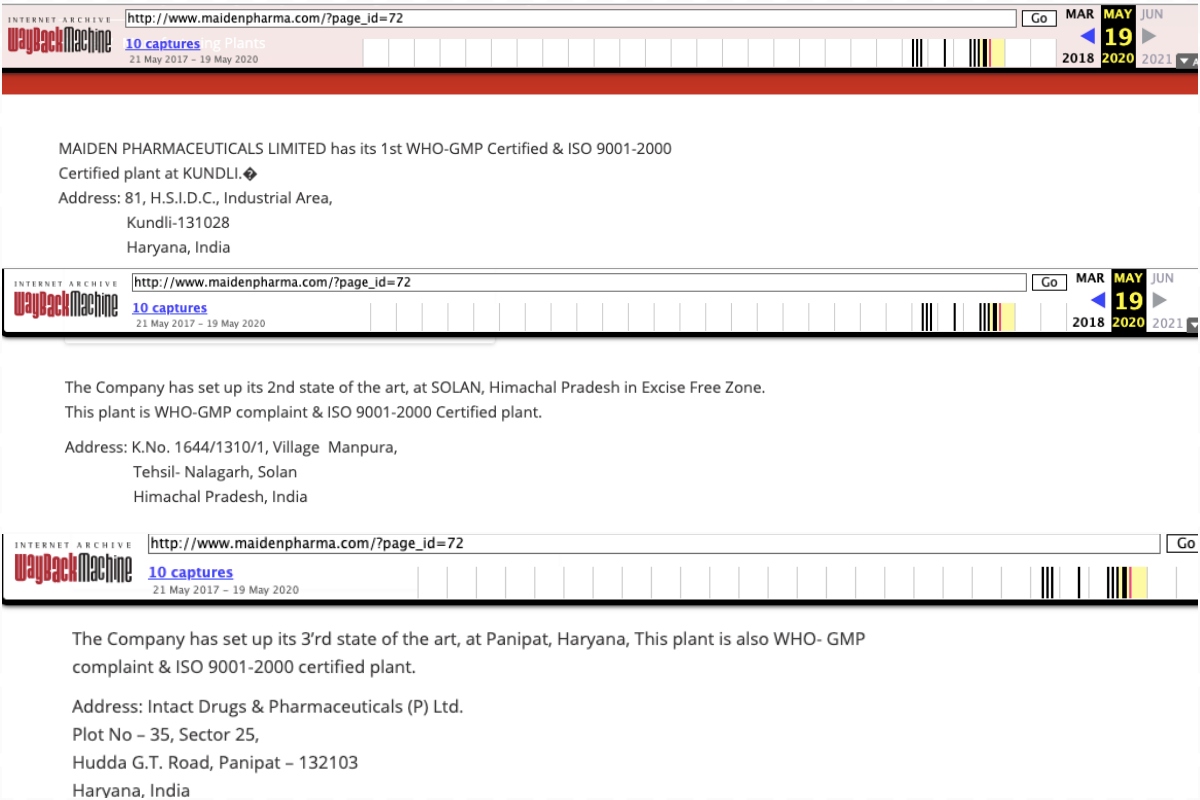

The company has claimed in the past on its website that its manufacturing facility in the Kundli district of Haryana had been certified by the WHO as complying with ‘good manufacturing practices’ (GMP).

(The website hasn’t been accessible at least since the WHO’s announcement yesterday. The Wayback Machine has a snapshot dated May 19, 2020, of a page on the Maiden website that claims its Kundli was WHO-certified.)

The same page claimed that two other plants operated by the company, in Panipat in Haryana and Solan in Himachal Pradesh, were “WHO-GMP compliant”. It was unclear if Maiden was claiming that these facilities had also been certified by the WHO.

Either way, a WHO spokesperson told The Wire that the organisation had done no such thing: “This manufacturer has not been inspected nor any of its products assessed in any way by the WHO.”

Collage showing Maiden Pharmaceuticals' claim on its website that its manufacturing sites are certified by the WHO as complying with ‘good manufacturing practices’. Collage: The Wire

Employees of Maiden didn’t respond to attempts to contact them over phone and email.

(A cursory search on two websites, iafcertsearch.org and 99corporates.com, also didn’t list Maiden among the Indian companies with ISO 9001:2000 certification, as the same Maiden webpage claimed. However, The Wire couldn’t further ascertain this.)

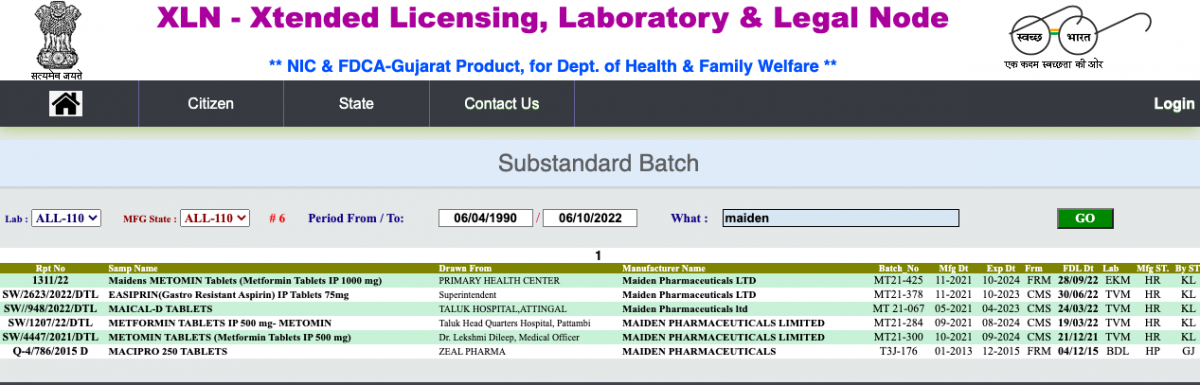

The Wire also found that Maiden has repeatedly produced substandard drugs in the past, yet was allowed to continue to operate. According to the eXtended Licensing, Laboratory and Legal Node (XLN) database maintained by the Government of India, at least two state governments – Kerala and Gujarat – have repeatedly warned of the company’s illegal practices.

(The state officials didn’t warn anyone in particular, but once the XLN database has an entry from a state authority, it is considered to be a red-flag.)

The eXtended Licensing, Laboratory and Legal Node (XLN) database maintained by the Government of India shows that Kerala and Gujarat governments have repeatedly warned of the company’s illegal practices.

Kerala authorities found Maiden’s products to be of substandard quality at least five times in 2021 and 2022. All of these units had been manufactured in Haryana.

Health department officials had picked up tablets of metformin – used to treat type-2 diabetes – from a taluk headquarter hospital in Palakkad in March 2022 and from a primary health centre in Ernakulam in September 2022. Both sets failed the dissolution test: the drug wasn’t able to dissolve properly in a given amount of time, thus failing to release the active ingredient into the body.

So the officials labelled the samples “not of standard quality”.

Another tranche of the same tablets failed the same test in Kerala in December 2021.

Also Read: Inside the Fight To Decide How Pure India’s Drugs Need To Be

Another drug, labelled ‘Easiprin’, picked up from a hospital in Kannur in June 2022 failed the salicylic-acid test – meaning the drug contained too much aspirin. Aspirin-poisoning has symptoms ranging from ringing in the ears to drowsiness and acute dehydration. Tablets of Maical-D, used to treat vitamin D and calcium deficiency, failed tests that checked their functional activity.

Maiden had manufactured these samples of Easiprin and Maical-D in its Kundli and Panipat plants.

Likewise, in 2015, authorities in Gujarat reported that samples of Macipro, a drug containing the popular antibiotic ciprofloxacin, had failed the dissolution test. This batch had been manufactured in Maiden’s Solan plant.

Note that the WHO has presently accused Maiden of contamination, whereas Kerala’s and Gujarat’s complaints aren’t concerned with contaminants.

This said, the questions hanging over the Haryana state drug control authorities are clear. Why didn’t their office take suo motu cognisance and investigate Maiden? Why did they not check for GMP violations?

Haryana state drug-controller Manmohan Taneja didn’t provide a definitive answer to The Wire. He only said he’d have to check the records. “Our entire focus is currently on the ongoing investigation” of the four cough syrups. “We will look for the track-record as our investigation proceeds,” he said.

According to Taneja, a team of experts from the Central Drug Standards Control Organisation (CDSCO) – India’s nodal body for drug standards – had collected additional samples of the syrup from the implicated batch for further tests on October 3. “The result should come within 10 days.”

(For every batch marketed, the manufacturer is required to retain a certain number of “control samples” from the same batch for future investigation.)

He explained that polypropylene glycol is added to the cough syrups to make them soluble. In the process, the manufacturer also added diethylene glycol (DEG) and ethylene glycol, which are contaminants because they have extremely toxic effects on the human body.

So, he said, the CDSCO has taken some samples of the polypropylene glycol for tests as well.

Asked if the team found any other physical lapses on the plant, he said, "We were not looking for any physical contraventions. At the moment, the entire focus is on the two contaminants."

Also Read: The Dangerous Irrationality of How Indian Regulators Classify Substandard Drugs

Taneja also claimed that these four products in question now had not been supplied in Indian markets. As far as export was concerned, it was only limited to the Gambia.

What is also to be noted is that the CDSCO team went to the company's plant on October 3, yet it did not issue any statement. It took the WHO to reveal the tragedy. The Wire tried contacting the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) on Thursday also, but in vain.

A collage shows the front labels and the back labels of the four contaminated products: Promethazine Oral Solution, Kofexmalin Baby Cough Syrup, Makoff Baby Cough Syrup and Magrip N Cold Syrup. Credit: WHO

WHO awaits India's response

Meanwhile, the WHO has told The Wire more than 70% of children who died in the Gambia were under the age of two years. The case fatality rate (CFR), that is the proportion of children dying vis-a-vis who got the disease of active kidney injury (AKI) due to the drug, was very high. "As of September 30, 2022, about 78 cases of AKI had been reported including, tragically, 66 deaths (CFR 85%)," the WHO has said.

The WHO also told The Wire that they are awaiting the response from CDSCO and its inspection report. It also clarified that four syrups were procured by the Gambian agencies directly and the WHO was not involved in the procurement.

The WHO was not aware if any pre-qualification test was conducted before the drugs were shipped to the Gambia. Neither the DCGI nor the CDSCO has said anything to this effect.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) speaks following his re-election during the 75th World Health Assembly at the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, May 24, 2022. Photo: Reuters/Denis Balibouse

Indian pharma companies a worry for LMICs?

The 66 deaths in the Gambia are not the first tragedy caused by sub-standard drugs manufactured in India. In the past, several low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) have either complained about receiving sub-standard drugs from India or have blacklisted Indian firms – damaging Indian claims of being the "pharmacy of the world". These incidents also raise questions about the laxity shown by Indian authorities in acting against the erring firms. One such example can be understood from a complaint from Vietnam.

On December 23, 2013, Deepak Mittal, the Indian consul general at Ho Chin Minh City in Vietnam, wrote to India's health ministry that the former had blacklisted 46 Indian companies for supplying substandard drugs.

"In view of the fact that a large number of Indian companies have been listed as defaulters by the Vietnamese authorities, it is requested that necessary background checks on these companies may kindly be undertaken in India to see if there are complaints against them from other countries and steps be initiated to penalise them for bringing bad name to the Indian pharma industries abroad," the Indian embassy wrote to the Union health ministry. Mittal attached a list of companies which were blacklisted.

Also Read: India’s Drug Testing Has a Big Blind Spot: Officials Rarely Check for Impurities

About two years later, T. Prashant Reddy, an advocate, filed a Right To Information (RTI) application with the health ministry to know what action was taken. He was told that following Mittal's letter in December 2013, the health ministry asked the DCGI to look into the issue in a letter dated January 2, 2014. About a month later, the DCGI asked all state drug controllers to investigate and keep the DCGI informed. But until April 2014, the health ministry did not receive any response. That is all the ministry could say.

In fact, a working paper released in 2014 highlighted the double standards of Indian manufacturers while supplying drugs to African countries. "Some Indian drug companies segment the global medicine market into portions that are served by different quality medicines," it said.

"While the notion of export grade marketing is familiar in other sectors such as agriculture, it appears to exist for medicines also, with Indian manufacturers exporting lower quality goods to Africa. They can do this because, presumably, African regulatory oversight is weaker (resulting in fewer registered products) as compared to middle-income countries, and because of reluctance to sell the worst medicines in India itself," the paper added.

The paper was authored by four researchers from the National Bureau of Economic Research – an American non-profit organisation. The Indian government and Indian pharmaceutical associations rejected the paper, saying it was meant to "tarnish the image of India".

A chemist shop in Mumbai. Photo: Reuters/Shailesh Andrade/Files

Indian-manufactured cough syrups also have a history of causing DEG poisoning due to contamination, even within the country. At least 13 children died in Himachal Pradesh earlier this year due to the consumption of syrup that was contaminated with DEG. Before this tragic event, drug regulators had found the firm’s drugs to be substandard at least 19 times – yet it continued to operate, just like Maiden Pharmaceuticals continued to operate even after the Kerala and Gujarat government flagged the substandard drugs.

Coincidentally, a new book on lapses in the Indian drug regulation system begins with the saga of DEG poisoning. In The Truth Pill: The Myth of Drug Regulation in India, Dinesh Thakur – the Ranbaxy whistleblower – and Prashant Reddy – the lawyer mentioned earlier in the story – talk about DEG poisoning leading to the death of 11 children died in Jammu in 2019. They too suffered from acute kidney injuries – just like the Gambian children. Some of the children who died in Jammu were as young as two months old, while others were six years.

This article went live on October sixth, two thousand twenty two, at forty-six minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.