Silchar (Assam): Taj Uddin Laskar, 43, is a mason and works as daily-wage labourer in the construction sector. Due to the pandemic, he was homebound and without work for more than a year. Working on residential plots has its drawbacks, as most people are not keen on employing a workforce who haven’t yet got the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. When asked if he could book himself an online slot, Taj Uddin said, “I have never gone to school, cannot read or write, and do not even have a smartphone, how am I supposed to book an online vaccination slot?”

Digital access

Digital inaccessibility affecting vaccinations led to temporary loss of employment opportunities for not just Taj, but an estimated 10 lakh construction workers in the state of Assam. The digital divide was laid bare within days of the Indian government announcing its nationwide digital vaccination drive for youth. With only 21% active smartphone users, Assam has the lowest number of smartphone users among all states in India; the state’s percentage is far below the national average of 33%. It is therefore not surprising that out of 3.1 crore people in Assam, only 30% of its young people have a smartphone. Out of those 30% youth with digital access, only a slim portion has been able to book a vaccine slot digitally in the first few attempts. The remaining has been glued to their electronic devices, refreshing the CoWIN site in hope of an empty slot.

Taj Uddin Laskar at work. Photo: Pompy Paul

One such young woman, Sagorika Chakraborty (28), a guest lecturer of physics at Cachar College, Silchar, narrates how she would constantly log in and out of the CoWIN portal,hoping to find vacant slots. Sagorika decided to book vaccine slots for her and her younger brother as soon as the Indian government announced it was extending its nationwide digital vaccination drive to the youth on May 1, 2021. “It hardly took me five minutes to register with CoWIN, but the actual struggle starts after that,” said Sagorika. Without any success in finding empty slots the during day, the brother-sister duo tried waking up early, as there was hearsay that the site has less traffic in the morning hours. Both the siblings would take turns to wake up at 4 am to search and book empty slots, but to no avail. “It was practically impossible to find empty slots over CoWIN, those who could book themselves a slot must be very lucky.” After daily attempts for about a fortnight, Sagorika stopped looking for empty slots online and started waiting for the offline vaccination drive to start for 18+.

While almost all Indians above the age of 18 faced issues with online vaccine registration and booking, things were even worse for those living in the periphery of the country. Cachar district in Assam is one of the most remote districts in India. The district shares an international boundary with Bangladesh, has limited smartphone users and poor internet penetration.

Also read: What Explains the Private Sector Not Being Able to Fulfil its 25% COVID Vaccine Quota?

Another local, Prasanna Shuklabaidya, 44, who runs a laundry shop in the Second Link Road area of Silchar, said, “I have a feature phone and I use it to contact my customers to collect and deliver clothes.” Expressing his anguish over the online mode of booking vaccine slots, Shuklabaidya said, “If it wasn’t for the one-week special vaccination drive on a walk-in basis organised by the district administration, Cachar in early June, I’d probably not be inoculated till now and that would have affected my already pandemic-hit business.”

Digital literacy

According to research published in 2018 by the Digital Empowerment Foundation, about 90% of rural India’s population is digitally illiterate. In a situation like this, the COVID-19 digital immunisation programme’s inequitable planning leaves a gap in its execution at the grassroots level and further worsens the existing socio-economic imbalance in our society. The possession and the ability to operate a computer and/or smartphone in both urban and rural areas are also scarce.

| Basic Digital Skills

|

Rural | Urban | ||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Basic Computer Skills | 12.6% | 7% | 37.5% | 26.9% |

| Basic Internet Skills | 17.1% | 8.5% | 43.5% | 30.1% |

Source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, 2019

Vaccine shortages

“A lot of locals had to go to cyber cafes to book themselves a vaccine slot as they do not have internet access. Many came to me, as I run a stationery cum printing shop. I tried and helped as many as I could,” says Milu Rani Sutradhar, head of the Meherpur gram panchayat.

“We had proposed four vaccination centres for the Meherpur gram panchayat, but only one vaccination centre was assigned in the area, and that centre too was functional for just one day when 230 adults were vaccinated on a walk-in token system,” said Sutradhar.

“Presently, no centre in Meherpur gram panchayat is providing vaccination as there is an acute shortage of vaccines,” she added.

Milu Rani Sutradhar, head of the Meherpur gram panchayat, in her stationery shop. Photo: Pompy Paul

Poor vaccine distribution and digital illiteracy are the two important factors affecting the vaccination drive in this part of the country. Rural India is home to 70% of India’s population and yet the divide is gaping in terms of vaccines administered in urban areas and rural areas. The shortage is true of much of Cachar district, where according to the CoWIN dashboard, only 53% of the population has received the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine – less than the national average of 58%. As for the state of Assam, 65% of total vaccination doses have been administered in the state thus far, according to CoWIN dashboard.

Vaccine accessibility

Online registration and booking of slots not only leave the marginalised behind in the vaccination drive but also disproportionately benefit those with internet access, modern gadgets, literacy, time at hand and an overall better socio-economic status.

It is a given that while most urban dwellers with easy access to resources will get vaccinated, the same is not the case with the rural populace. Inequitable planning of the COVID-19 immunisation programme leaves a lacuna in the implementation of the programme at the grassroots level.

Many from Cachar district drove to neighbouring districts of Karimganj and Hailakandi to get their jab, as and when they could not find a slot in their area of residence.

“Yes, having a vehicle has its benefits. I could drive myself and my brother to a vaccination centre in Lala, in Hailakandi district, as it was impossible to get a slot in my area,” said Pallav Singh Yadav, a 26-year-old resident of Meherpur gram panchayat in Cachar district.

“Because of the inter-district travel ban in Assam, there was heavy police patrolling on the highway and they would only let vehicles pass after showing e-registration slips. However, I didn’t mind driving the distance because I got the slots after trying for five consecutive days due to high traffic on the CoWIN site,” added Pallav.

Volunteering and community aid

In order to reduce the stretching divide, a lot of young people in Cachar have volunteered to book slots for those who were unable to do so themselves. Local youth, both in their individual capacity and those affiliated with social organisations, have provided people with digital support.

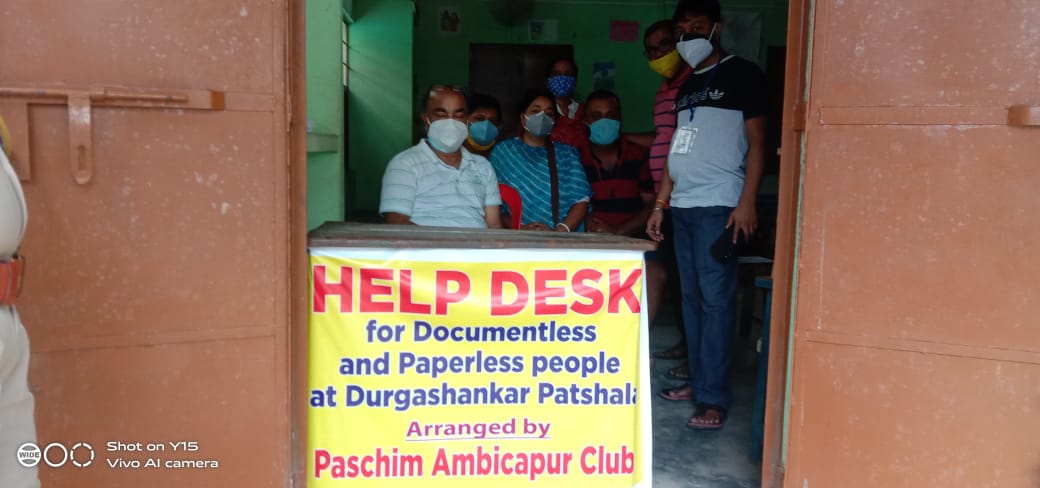

The Paschim Ambicapur Club in Silchar is a socio-cultural club. Noticing the troubles people were facing while booking COVID-19 vaccines, the club decided to step in. It provided assistance to those without any valid identity or documents with online vaccine slot booking, and also helped with crowd maintenance in one of the busiest vaccination centres in Cachar. “We assisted people from all sections of society with vaccine registration and slot booking over CoWIN. It was difficult for us initially as there were long queues for vaccines and most people who came for vaccination didn’t own personal phones,” said Aritra Dhar, a social worker with the club.

Also read: Nine Months Later, 25 Takeaways From the World’s COVID-19 Vaccination Programme

“Most people that I booked vaccine slots for were smartphone owners and internet users, and despite that, they were unable to book a slot over CoWIN,” said Shobraj Chakraborty, who runs a music store in Silchar. “This tells you how tedious and exclusive the process could be even for those who are technologically fluent.”

“High traffic on the CoWIN portal during the booking makes the process difficult and hence I could only book a slot after not less than five attempts,” said Saikat Das, a local youth who helped in creating a database of phone numbers of ambulances and other emergency services across the state. Saikat, in his personal capacity, also helped three people by booking online vaccine slots for them.

Paschim Ambikapur Club Covid Help Desk. Photo: Aritra Dhar

Remedial measures

A smaller number of smartphone users and poor internet penetration has jeopardised equitable chances of receiving the vaccine. Taking into account the plight of those who were unable to access vaccines through online registration, the district administration of Cachar started a special walk-in vaccination drive in all 28 wards of Silchar municipality and eventually also in gram panchayats that fall under the Silchar Anchalik panchayat.

“Around 49000 beneficiaries have been vaccinated with Covidshield across the 28 wards of Silchar in a week’s time. A GP wise vaccination campaign was also taken up across all 8 medical blocks with walk-in registration for all people above 18 years of age,” reported Cachar’s district administration.

People from all sections benefitted from the special walk-in vaccination drive, but it was especially helpful to those belonging to vulnerable communities and without access to digital resources. People like Taj Uddin Laskar and Prasanna Shuklabaidya would have been still unvaccinated if not for the walk-in drive. The special drive was also beneficial for people who could not book an online slot despite having digital literacy and access. The fact that a record number of people turned out for the district’s walk-in vaccination shows that it was a success, especially for those who couldn’t acquire the vaccine through online registration and booking.

“Online booking is done to taunt the poor like us,” concluded Taj Uddin Laskar. “We can barely afford to live.”

Pompy Paul is Silchar-based independent journalist and researcher. This story was reported under the National Foundation of India Fellowship for independent journalists.