The US Is the WHO’s Biggest Contributing Country. Its Exit Could Jeopardise the Agency's Work

On his very first day in office, US President Donald Trump announced Washington’s withdrawal of support to the World Health Organisation (WHO). The stated complaint is WHO’s supposed mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There could be some legitimate questions on how the WHO functioned during the pandemic. This is still being debated. But the reasons for a US withdrawal could be much more fundamental than what is being stated officially.

The WHO represents a world order of multilateralism, solidarity and internationalism that is facing numerous threats from multiple fronts. The US withdrawal needs to be seen as the culmination of a process of the delegitimisation and weakening of the WHO that started almost three decades ago.

Let’s look at the WHO’s funding architecture to understand the possible implications of the US withdrawal.

The WHO has two main funding sources. Its core funding comes from its member states. This funding is categorised as ‘assessed contributions’ (ACs).

A member state’s ACs are determined using UN funding criteria fixed in 1982 that factor in the size of that country’s economy and population. A majority of the WHO’s ACs come from the big powers of the world from the Global North like the US, UK and Germany.

ACs are ‘untied funds’, that is, the WHO can use them at its own discretion, once approved by the World Health Assembly, the WHO’s highest decision-making body composed of all member states.

In addition to this, the WHO receives ‘voluntary funds’ in the form of extra-budgetary funds (EBFs) from various development agencies, charities and private philanthropies, NGOs and other UN agencies.

These donor organisations may ask the WHO to use their EBFs for specific programmes that may be guided by their own priorities and agendas. In other words, the WHO may be constrained from using funds falling under the EBF category for programmes that it wants to prioritise, and therefore these are not ‘untied funds' – in that sense.

Starting in the 1980s, the quantum of ACs that the WHO received remained virtually frozen. Moreover, many member states could not contribute as well. The WHO had to depend more on EBFs from various organisations, which are for the most part ‘tied’ funds. Not without reason, there is fierce competition among organisations working on global health for these funds.

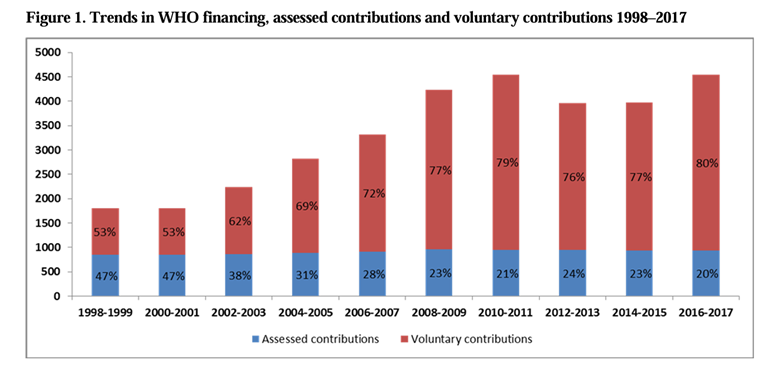

Source: Global Health Watch 5, Peoples’ Health Movement; adapted from WHO’s financing dialogue.

Although a sizeable proportion of EBFs came from UN agencies during the 1980s, private philanthropies (such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF)) and partnerships like the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation or GAVI are among the biggest contributors to the WHO today.

As far as individual countries are concerned, the US is the biggest donor. Although when one takes into account all countries as well as private and non-profit philanthropies, the BMGF is the biggest funding entity, followed by the US.

As an aside, the overall budget of the WHO is quite modest. It was roughly around $5 billion for two years (2020-21) – smaller than the budget of a sub-regional hospital in Germany or France.

Currently, ACs make up one-fifth of the total WHO budget, thus accounting for $1 billion. The US contributed one-fifth of the total donations made by individual countries. Thus, the US’ contribution to the WHO’s funding, in the form of ACs, was around $200 million.

A US withdrawal from the WHO would mean that some of these funds would not be available from the next funding cycle.

As stated before, the relative composition of ACs and EBFs has changed. EBFs comprised 20% of the total WHO budget in 1970. A big chunk of it largely came from other UN organisations.

However, over the years, the share of EBFs grew to around 80% by 2016-17 (Figure 1). Now, the US withdrawal from the WHO may increase the say of private philanthropy organisations further.

The road ahead

In April 2020, the Trump administration made a similar announcement of withdrawing its ACs. Several European countries responded by increasing their funding to the WHO, as did other member states. The crisis could be averted this time too.

In fact, there remains a lot of scope for member states to increase their individual ACs.

It is high time that the issue of increased ACs is reopened and new criteria evolved keeping in mind the new geopolitical realities and the increased role of LMICs in the world economy.

For instance, in the year 2022-23, the Indian government spent around Rs 100 crore on international cooperation. Only a part of it went to the WHO.

The WHO emerged from an atmosphere of global solidarity after World War II and the decolonisation of the ‘Global South’ as the UN’s specialist agency for health in 1948. It represented the aspirations of the developing South.

It was credited with multiple global achievements like the eradication of smallpox and the effective management of multiple epidemics. The Alma-Ata declaration of the WHO and its call for ‘Health for All’ by 2000 in 1978 was one of the most promising moments of the history of third world solidarity in health.

The WHO has been instrumental in developing technical capacities in the Global South, albeit with limited success.

The WHO has also been critical of the role of large transnational corporations and tried to regulate health-harming products. It raises concerns against patents and the monopoly of big pharmaceuticals. The influence of big pharma and transnational companies remains largely indirect in the WHO, through their presence in the boards of large philanthropies and alliances.

The major issue for the WHO now may not be about resources – the US withdrawal could be a reflection of the increasing hegemony of big money and the deep state in global politics.

Trump’s withdrawal could be seen as an assertion of more direct control over global health politics and the global order, in general, by the alliance of transnational capital and a conglomeration of right-wing states that Trump represents.

However, Trump’s move could also become a harbinger of change – a wider alliance might emerge from this crisis. These emerging economies of the world may come together on a scale larger than ever before and reinstate a sense of solidarity; and a more healthy and humane global order.

Therefore, Trump’s attempt to pull out the carpet from underneath the WHO may well help this global health body get bigger wings and fly higher.

Indranil is a health economist and a professor at School of Government and Public Policy in O.P. Jindal Global University.

This article went live on January twenty-fifth, two thousand twenty five, at forty-four minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.