A 387-Year-Old Dutch Lodge in Maharashtra's Vengurla Gets a New Lease of Life

Vengurla, a quiet beach town on the west coast of India, is looking forward to restoring a 387-year-old Dutch building to its former glory, hoping it will turn the tide and attract global tourists, at least from the Netherlands.

“The restoration will prove monumental for Vengurla – only if implemented well. It is crucial to preserving ‘our’ history,” said Dr Sanjeev Lingwat, who runs a homoeopathic clinic in town.

Dr Sanjeev Lingwat his clinic. Photo: Reuben Malekar

The 52-year-old Lingwat, a confessed history buff who would rather be exploring ancient caves and medieval hill forts in the town’s vicinity than spending long hours in a clinic, has been campaigning to preserve the crumbling colonial monument.

Historical records reveal that the building was abandoned by representatives of the Verenigde Oost-Indische Campagnie (VOC) or United East-India Company in 1685.

Yet, I was told, the Dutch stone house, variously referred to as the ‘lodge’ or ‘factory,’ was an archaeological marvel, listed as a protected monument in 1974 by the Maharashtra Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act of 1960.

Bauke van der Pol somewhere in Turkey in 1974 on his way to India, the then young Dutchman did an on road Eurasian trip from the Netherlands to India. Photo: Bauke van der Pol.

Bauke van der Pol, a Fries anthropologist-historian from Harlingen and author of the 2011 coffee-table book De VOC in India: A journey through Dutch heritage in Gujarat, Malabar, Coromandel and Bengal had visited Vengurla in 2010. He attributed its appeal in the popular imagination to the fact that “it is the only lodge from the VOC period in India that still exists".

Years of neglect had somehow pushed it into relative oblivion. Many among the present 12,000 or so citizens of Vengurla could not be bothered, nor were the Dutch back home, some 7,000 kilometers as the crow flies.

To be fair, the Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANP) news agency wired a story a decade ago – in June 2013 – about the Dutch building on the “verge of collapse”. It was picked up by the Dutch media including De Volkskrant, De Telegraaf, Het Algemeen Dagblad, Trouw, Het Parool, and De Reformatorisch Dagblad, besides some others from North Holland to Limburg, and Zeeland to Groningen.

Silence followed.

The Dutch factory, or “vakhar” (warehouse) in the native Indian language, would keep propping up in the local newspapers.

But that was it – nothing happened.

“Our hands are tied,” Rajan Girap, mayor of the Vengurla Municipal Council, told me. “It is the archaeological team’s job to restore such old buildings.”

I contacted Shekhar Samant, the editor-in-chief of Tarun Bharat, a popular newspaper in the local Marathi language, which had carried several stories on the Dutch “vakhar”.

The entrance to the estuary towards the Dutch 'vakhar'. Photo: Reuben Malekar.

He appeared skeptical but enthusiastic while letting out an important piece of information.

Samant was born and grew up in Vengurla, in close vicinity of the Dutch stone house. “We published a story on August 15, 2023, about a proposed restoration project. But you will have to contact the archaeological survey authorities to confirm the status,” he said.

I decided to have a look at its condition myself before contacting them.

A narrow lane in the old town led me to the building with a worn-out noticeboard nailed at its entrance: “Dangerous structure. Do not enter…!” it warned.

I continued in my quest, though cautiously, hoping that things wouldn’t fall apart. The four visible bastions and stoned-ramparts around the main structure looked as if they could give way at any moment.

The inner courtyard was covered in a jumble of thick shrubs and tall trees, with an assortment of creepers and climbers hugging the building on all sides.

The common Indian garden lizards were running riot on the broken walls of the main structure. It was as if nature had reclaimed the ghost lodge – providing cover from the vagaries of time.

One might as well turn this into a hotspot for the native wildlife to thrive.

But the empty liquor bottles strewn all around provided a telltale sign that the building was still serving a human purpose, as a refuge for the tipplers in town, away from the prying eyes of a conservative town, where drinking remains a social taboo.

The property appeared cramped and ill-planned. But then, even pieces of art when viewed at close quarters tend to appear more ordinary than you imagine!

Walking away from it and then turning back did provide a better view – the building looked like the “fine, luxurious lodge” described in a 1996 study by Frans Ambagtsheer and Leo Wevers, ex-architectural researchers at Technische-Universiteit Delft.

“Among the very austere VOC architecture, this lodge with its vaults and cassette stuccowork is really an exceptionally beautiful building,” they had noted.

Ambagtsheer and Wevers also explained that “by means of the architecture of the building the founders of the lodge, in 1637, obviously intended to underline its strategic and commercial significance”.

****

Vengurla is as far from India’s commercial hub, Mumbai (formerly Bombay), as is Winterswijk – where I stayed while pursuing a master’s programme at Radboud University – from the hustle-bustle of the Randstad. The coastal town is located on the southernmost tip of the western Maharashtra state and lies approximately 500 kilometres south of Mumbai, which also happens to be the state’s capital.

About 50 kilometres further south is Goa, the paradise for global tourists.

A typical, quiet afternoon in Vengurla. Photo: Reuben Malekar

A Portuguese colony until 1961, this tiny western Indian state with its sun-kissed sandy beaches has transformed over the decades from a mecca for hippie backpackers to a much sought-after destination for both foreign and Indian vacationers.

Vengurla lacks Goa’s magical appeal. It is modest on tourist trappings and oblivious to its natural charms. The untouched beaches, quaint old houses, and ancient temples render it a rustic and thoroughly native look.

It is the perfect weekend destination for those in search of some quietude.

However, the town’s residents seem dissatisfied with their anonymity on the global tourist map. The international tourists are all flocking to Goa, they grumbled.

I chanced upon Vengurla while on a family holiday five years ago. And decided to return, pulled by its simple charms.

The only person I knew there happened to be a Dutch lady, who had exchanged a couple of emails with my father, a journalist.

Hanny Mensing, an 85-year-old Nederlander, was living with her Indian partner in a small village called Math on the periphery of Vengurla.

On my first phone call, I would hear her heavily Dutch-accented English coupled with oodles of energy for someone born before World War II.

Hanny would welcome me into her house. “You are an independent journalist, I understand – I have been an independent translator all my life. We can skip the money part. You can stay here as long as you want.”

It was December and weirdly warm, except for the cool coastal breeze in the evenings.

The Dutch lady hadn’t the slightest clue about Vengurla’s Dutch connection until a year after she settled in Math.

“Before I came to India, I had never known about VOC’s presence here. In South Africa, yes, In Nederlandsch Indie or Indonesia, of course, yes, the Caribbean Islands – with the WIC (Westindische Compagnie, or the West-India Company), also yes – but India? It was simply not in the curriculum,” she exclaimed.

Hanny moved to Math in May 2008 and couldn’t be bothered about a “factorij” built by the Dutch as she got busy building her own house – “a nerve-wracking experience you should avoid at all costs,” she told me.

Nonetheless, the occasion came when her friends from the Netherlands came to visit. She faintly remembers it was sometime in 2009 or 2010 that she asked a three-wheeled auto-rickshaw driver she regularly hired to take her to the Dutch “vakhar” while out on an errand.

“I had to make plans for some outings before my friends arrived – you know, the Dutch and anticipating everything – and, without any Taj Mahal-like sightseeing attraction nearby, the only thing that popped up was the Dutch vakhar,” she winked.

The rickshaw driver appeared clueless. After seeking directions from multiple, equally uninformed passersby, they finally landed at what turned out to be a “gas station”, a distribution point for domestic cooking gas cylinders.

“Nobody there understood why anyone, least of all a foreigner, would be interested in looking at the garbage dump. Not even after the foreigner explained there was a certain link between ‘being Dutch’ and those ruins,” she laughed.

Hanny recalls walking toward the entrance and peering inside to find three to four shoddily clad men hovering around. “It was definitely not welcoming and certainly not very appealing for me.”

A few curious onlookers soon gathered around the auto-rickshaw suggesting her driver to take her away. They even gestured to her, not to step any further as it was raining rubble out there.

Hanny stepped back and never went there again. She discovered more about the “vakhar” in 2011, via Bauke van der Pol’s book.

The octogenarian who keeps busy developing her sacred garden with only Indian, native plants with the help of a two-workman army imagines the challenges the Dutch must have faced in the 17th century based on her own experiences.

Funnily, there’s communication chaos as she speaks English with a Dutch accent and they speak only Malvani (a close relative of the Marathi language with slight coastal variations, like Limburgish) language – they smile, say hello, and wave their hands to indicate if it’s ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a given task.

Moreover, the Indian work ethic doesn’t correspond with Dutch punctuality. More often than not, “I find it indeed often very difficult to deal with”, she stated.

****

The stone house in Vengurla could have long been forgotten and met with a quiet burial by now but for Dr. Lingwat’s patience and tenacity, and Tarun Bharat’s consistent reporting.

The homoeopath had taken time out from his clinic to pursue his “passion project” for over a decade now. He had lost count of the number of visits he made to the archaeological department’s regional office in Ratnagiri, a three-hour drive from Vengurla.

As the nation celebrated Independence Day, on August 15, 2023, the news about the restoration plan taking concrete shape was broken by Tarun Bharat.

An official document said the “restoration and conservation” work would be undertaken at an estimated cost of 28,416,860 Indian rupees (around 315,000 euros).

I spoke to Shantaram Khekade, a junior engineer tasked by the government to oversee the project. “We intend to give support to the structure of the building by using L-shaped steel pillars and also chop down the overgrowth around the factory,” he said.

The work was to be accomplished in 12 months, excluding four months of monsoon between June and September, when Vengurla experienced heavy rains.

I also contacted the Dutch embassy in India. Wichter Slagter, a Dutch official, was heavily interested in the restoration and development plans of this building but there was no cooperation mechanism between the embassy and the state’s archaeological team. "We have not been contacted by the archaeology department or the local authorities," stated Slagter, who serves as a deputy for political, public diplomacy and culture affairs for the embassy based in New Delhi.

Not much later – on February 15, 2024, Tarun Bharat published another story announcing the restoration work had begun. It was headlined, “Dutch Lodge in Vengurla to be conserved; Success for Dr. Sanjeev Lingwat’s follow-up”. It carried a photograph of the scaffolding around one of its bastions.

A beaming Dr. Lingwat described it as a “major development” in preserving the history of the town. “It will bring to life a glorious era when Vengurla was an important port in western India,” he said.

In his modesty, and to my surprise, he also thanked “the Dutch and especially Johan van Twist who built the lodge.”

This van Twist was a Dutch merchant, who arrived in the winter of 1636 as a VOC representative to do what the Dutch did best – negotiate a trade agreement with Sultan Mohammed Adilshah of Bijapur.

By New Year’s Eve of 1637, the Dutch merchant had convinced the sultan to grant the VOC access to markets in his kingdom. But trade wasn’t the only motivation, as some historical accounts pointed out.

The VOC and the Bijapur sultanate also devised a military plan to expel the Portuguese who had established themselves as masters of the Arabian Sea along much of the narrow Chile-like, continuous strip of land, locally known as the Konkan.

India’s western seaboard was a reservoir of foreign immigrants — Arabs, Jews, Siddis (Ethiopian military slaves), Portuguese and English — settled in pockets, some of them arriving several centuries ago.

As the latest entrants to the Indian Ocean trade world, the Dutch had their eyes set on the fabulous cargoes of pepper and spices introduced to the Western world by the Portuguese, their arch-rivals back home.

The Dutch traders were barred from important markets at Lisbon and Cadiz in Spain after their lot had broken away from Roman Catholicism to form Protestant churches in the latter half of the 16th century. And trade was difficult to establish in India so long as the Portuguese remained unchallenged in Goa.

Theirs was an old European rivalry about to be played out in this part of the Indian subcontinent.

The Dutch had already joined hands with their English counterparts to starve the Portuguese of trade and essential supplies and try to take over their possessions.

They had launched joint operations in the monsoon of 1621 to blockade Goa, but soon realised it was difficult to sustain them from Surat in India, where the English East India Company had gained a footing in 1612, and Batavia in the Indonesian islands, where the VOC had its eastern headquarters.

What they lacked was an ideal base close by to monitor and support the Goa blockade.

And so, the Dutch had zeroed upon the tiny port located a little north.

Vengurla was described by Dutch officer Philippus Baldaeus as “...a place very comfortable, not only for its plenty of wheat, rice, and all sorts of provisions but also for its proximity to Goa”.

It could serve as an ideal lookout post (uitkijkpost) over Portuguese activities in their paradise, which the Dutch merchant and historian Jan Huyghen van Linschoten wrote was full of “lovely women” and “streets covered in gold.”

The lure of Goa was hard to resist for the die-hard traders.

****

The Dutch lodge built in European style added a different spectacle to the landscape dominated by palm trees, which stood tall alongside the hills that sheltered the bay of Vengurla, except in the south, where the port was located for easy movement of boats.

Fishing boats parked on the Vengurla beaches with a flag of 17th century Maratha emperor Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj.

Today, this port has transformed – not with a modern touch, but geographically. Over time, the sea waters have pushed the sand up Vengurla’s coastline making it impossible for boats to reach the Dutch building which only remains accessible from land now.

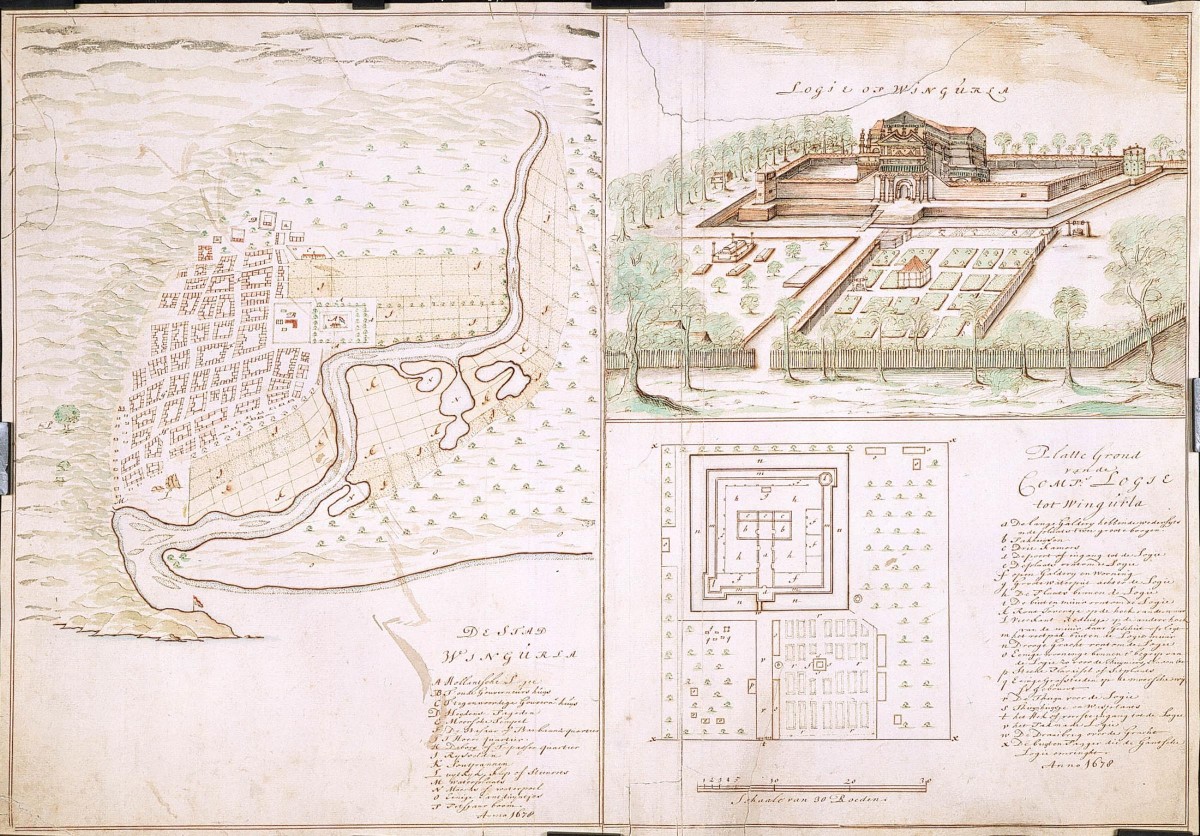

This remains contrary to what Isaac de Graaf – a Dutch cartographer – drew in 1678 where the Mandavi estuary waters can be seen kissing the property where this building is located.

Isaac de Graaf's work from 1678. Photo: Atlas of Mutual History Netherlands.

In 1637 – the foundation year – it was only a T-shaped structure surrounded by an earthen rampart and a defensive moat, which was only filled with water during the rainy season.

The strategic location across a swamp afforded a view of the navigable estuary, which served as an access to the nearby harbour. Further away lay a foul ground caused by the sunken Vengurla Rocks, some four nautical miles offshore. Navigating it was always fraught with dangers, especially for the uninitiated intruder.

The Vengurla Rocks are today home to a lighthouse and swiftlets – little birds who like to roost in the tiny caves of those submerged rocks. Also, the government is pretty serious about their conservation as gathered from official advisories!

Anyway back to the lodge where the strengthening of its defenses was taken up by the then-chief merchant Cornelis van Sanen who wrote to Batavia on November 17, 1643, seeking funds for a stone wall to replace the earthen works that couldn’t stand heavy rains. The proposal was duly honoured!

And today, you see the strong-stoned walls along with the surrounding bastions that you do!

The cancerous dilapidation today hasn't yet spread to the traces of this fort-like structure with extensive walls, strong bastions, and gates that would’ve been well protected during conflicts and emergencies by guards manning heavy cannons.

A shallow well, which would have served as the main water source, still lies intact. The confined spaces on the ground floor appear large enough to store food and other supplies.

The dilapidated first floor of the lodge. Photo: Reuben Malekar

The second floor remained more-or-less of the same orientation while the top-third floor, approachable by a staircase, was used as a watch-out tower by the factors which led the Goa offensive from 1636 to 1644, and later between 1657 and 1662.

Today, the roof of the third floor has disappeared – where the actual structure remains openly-exposed!

The lodge’s main purpose was to support the Dutch armada during the blockade of Goa, supplying water, food, and medical assistance, while also acting as a lookout post.

Vengurla was thus drawn into what historians call the “Crisis of the 17th Century Coastal Western India,” an outburst of naval warfare triggered by the Dutch-English joint offensive against the Portuguese.

The tiny port’s fortunes came to be closely associated with Dutch strategic and mercantile interests, and waxed or waned accordingly in the coming decades.

The naval superiority of the Dutch fleets over the slower and bulky Portuguese carracks played a key role during the conflict, hindering the movement of ships from Goa to Lisbon, Cadiz, Macao and China. It virtually paralysed Portuguese overseas trade of expensive goods.

On the other hand, the relatively peaceful relations between the Dutch and the Bijapur court, as well as the indigenous Marathas led by Shivaji, ensured a steady growth in Dutch trade.

By the mid-17th century, Vengurla was transformed into an important entrepot as the VOC established trade links all along the Indian Ocean rim – Surat, Hormuz, Basra, and the Red Sea on the one hand, and Malabar, Ceylon, Bengal, Batavia and Japan on the other.

The east side of the Dutch lodge as photographed from the southern edge: Photo: Reuben Malekar.

Commodities like cotton, molasses, hemp, grains, clarified butter, groundnuts, cloth, tobacco and spices were traded through Vengurla. Some of the local items of exports included coconuts, betel and cashew nuts, kokum oil, coir fibers, salt and cardamom.

However, the Dutch connection and thriving trade would last roughly five decades, until 1692.

****

Unlike the British, Portuguese and French, the Dutch presence in India was limited, in every respect. But their shared past with Vengurla does raise the query about a likely impact on the native society.

It hasn’t been long since the Chains of the Past report surfaced and took the Netherlands by storm, or the Slavery History Dialogue Group Advisory Board was set up on July 1, 2020, tasked with organising a dialogue within the country about the history of slavery and its impact on modern society.

In Vengurla, exploring the issue proved an impossible task. There is little awareness about the VOC and its wealthy Dutch merchants who travelled overseas to trade in early 17th-century Asia.

“If the Dutch were here in large numbers then where is the evidence? Have you found any graveyards?”asked Devdutt Parulekar, a well-respected and prominent advocate in Vengurla. In his opinion, exploring the aspects of Dutch slavery, or other ill practices, can be difficult in this small town’s popular imagination as very little is known of their near-half decade of activities in this region.

Devdutt Parulekar at his residence with a 'warli' (Indian indigenous tribal) art in the background. Photo: Reuben Malekar.

This perhaps gave the Dutch some benefit of the doubt, unlike their arch-rivals, the Portuguese, whose legacy in India is a mixed bag tilting on the negative side due to the forced conversions, inquisition, and their refusal to quit – Goa had to be liberated and reclaimed after more than four centuries under Portuguese rule.

The British, of course, were the chief colonisers for nearly 200 years and what their rule did to India has been well explained by historian William Dalrymple: “The economic figures speak for themselves. In 1600, when the East India Company was founded, Britain was generating 1.8% of the world’s GDP, while India was producing 22.5%. By the peak of the Raj, those figures had more or less been reversed: India was reduced from the world’s leading manufacturing nation to a symbol of famine and deprivation.”

Vengurla was also visited by American missionaries who did pioneer work in the fields of medicine and education in the 19th and 20th centuries. But the conversions to Christianity continue to rankle the Indian mind. “Through healthcare, their hidden agenda was evangelism or religious conversions,”said Prashant Apte, a corporator in the Vengurla Council – equivalent to a Gemeenteraadslid.

None of these negative aspects of imperialism seem to stick with the Dutch, at least in Vengurla.

Bauke van der Pol who has extensively researched the Dutch Indian historical relations – his latest work Dutch Heritage in Fort Cochin, Cannanore and Quilon will be released this year – explained that while interpreting this shared history “dualities remain prominent and should be explored further".

It is not unusual to find Indians who view the colonial occupations in a positive light, he said in a video call, but historical records do reveal traces of grave atrocities, including the trade of slaves at numerous VOC trading posts on the Indian coastline.

“The slaves at Dutch factories in India included a majority of the lower caste Indians,” explains van der Pol, who first came to India in 1974 for fun and would continue visiting later as a student at Leiden University to research an untouchable caste called the Pulayas in the southern Indian state of Kerala, where the Dutch were a colonial power.

The lower castes in India have historically been disadvantaged compared to the upper castes “which might help explain the duality within Indian society about their Dutch connection”, he added.

Hence, opportunities offered by the VOC might have helped the disadvantaged better their social positions in that era, according to van der Pol.

Rene Barendse, another Dutch historian with his academic roots in Leiden, writes in his renowned 2002 book The Arabian Seas: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century how the VOC put Vengurla on the international map, when “around 1670 it was still but a hamlet containing about 8,000 inhabitants”.

“The prosperity of Vengurla very much depended on the protection of the VOC and the demand of the ‘offensive fleets, sent by the VOC to blockade Goa’. Additionally, the history of this hamlet was intricately linked with the purpose of the VOC in Vengurla,” he suggests.

The Vengurla Jetty. Photo: Reuben Malekar

Barendse refers to the town serving as a refuge for upper-caste Saraswat Brahmins expelled from Bardes – a part of North Goa – which was then a part of the Estado da India (Portuguese State of India) where being Hindu was not an option during the Goa Inquisition – a move influenced by the Counter-Reformation (or Catholic Revival) taking place in Europe.

“The Inquisition engaged in forced conversions, persecutions of Hindus and the destruction of Hindu temples – when Vengurla might have offered the refuge needed in desperation,” he notes.

When I contacted Caroline van Overbeeke, spokesperson for Leiden University, during the New Year of 2024 for a bridge to Dr. Barendse – my request paid no heed. “I am very sorry, Reuben, but this person is not working at Leiden University anymore (but he did) many years ago”.

What Barendse’s keen assertions on Vengurla show are that the Dutch – who challenged Portuguese supremacy in Goa might have come to be viewed favorably here.

But what seems to have worked in their favour, at least in Vengurla, is the accounts of local historians – especially, Sachin Pendse, who died in 2018, and Nikhil Bellarykar – portraying fairly good, diplomatic relations between the Dutch and the native Marathas, specifically the iconic Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj who opposed the Mughal dynasty and founded the Maratha kingdom in 17th-century India.

“This is indeed as much about preserving Maratha history as it is about Dutch history," stated Dr. Lingwat.

Shivaji was well disposed toward the Dutch and wanted to revive trade at Vengurla, the Maratha historians contend, but after he died in 1680, the Marathas were pitted against the Mughal forces who blocked all trade routes in the region.

The Dutch too shifted their focus away after the factor at Vengurla received orders from Batavia to stop investing any more resources on the ‘uitkijkpost’ and instead report to Cochin, having secured control over and established their stronghold in the heart of present-day Kerala’s spice country.

The Dutch finally abandoned the property in 1693 and thus began Vengurla’s steady decline until it was ceded to the British in 1812.

After the British conquest of India, the Dutch lodge came to house the town’s administrative offices and the subordinate judge’s court, which functioned out of it until the late 1960s when the building finally fell into disuse.

The elderly in Vengurla recall the talk about preserving it during the prime ministership of Late Indira Gandhi – India’s Iron Lady – in the 1980s but by then the wooden furniture and fixtures were already stolen and the building was reduced to a haunted ruin. A grim reminder of a Dutch era gone by!

****

After my visit, Hanny Mensing and Dr. Sanjeev Lingwat have turned good buddies. They both keep busy with their lives – Hanny with her land and Dr. Lingwat with his expeditions to forts – and other historical places.

Hanny and Dr Lingwat with the workers from Bijapur. Photo: Sanjeev Lingwat.

He has a YouTube channel – updated frequently – and when he meets Hanny, it’s almost always a million photographs. Hanny calls him her “personal photographer” now and believe me: the man likes to capture everything – he really likes his camera.

On March 19, it was Hanny’s day out with Lingwat. “I get my first guided tour this afternoon,” she texted me.

The site has lost its abandoned status and is overflowing with life!

As observed by the Hagenaar or Hagenezen, as she corrected me recently when I loosely referred to her as a Den Haager, “there is a very alert supervisor and 15 very hard-working people – mainly women” working on restoring the lodge.

What’s more notable? They are from “THE BIJAPUR”.

It all started from the VOC-ambassador Johan van Twist’s diplomatic tour to Bijapur in 1637 on New Year’s eve to secure trading rights and today, ends with these Bijapuri men and women trying to bring back to it the shine and glory it deserves.

Well, at least for Vengurla and its folks!

This article went live on June twelfth, two thousand twenty four, at fifty-nine minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.