Why Has India Forgotten Ahmed Kathrada?

When Walter Sisulu – a giant among South Africa’s anti-apartheid leaders who spent 25 years in jail – passed away on May 5, 2003 at the ripe old age of 91, India’s then prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee said in his tribute: “We shall remember him for his warmth and personal simplicity. He was a rare political personality who had a stature that did not depend on status.”

This tribute appears in the autobiography of another legendary personality in the same struggle, Ahmed Kathrada, who venerated Sisulu as his mentor and “father”. Indeed, Vajpayee’s words accurately describe Kathrada’s personality too. For he belonged to that golden generation of South Africa’s selfless freedom fighters to whom transitory status meant nothing; their immortal stature was formed in the crucible of lifelong struggle and sacrifice for the lofty dream of building a better world.

When it comes to celebrating high achievers among members of the diaspora, we Indians are so status-obsessed that we often ignore, even forget, those with stature that does not depend on power or wealth – especially if they are not from Europe or America. For example, Kamala Harris, Rishi Sunak, Sundar Pichai and Satya Nadella have become household names in our country. True, they have remarkable accomplishments to their credit.

But does anyone remember Ahmed Kathrada? The name is unfamiliar to most Indians. Even a vast majority of people in our political and media establishments would be dumbstruck if asked about him. This is extremely sad. All the more so since India’s freedom struggle had such a defining influence over South Africa’s liberation struggle. Furthermore, the values for which he struggled all his life – non-racialism, non-sexism, inter-religious harmony, equality, justice and human dignity – remain universally relevant even today.

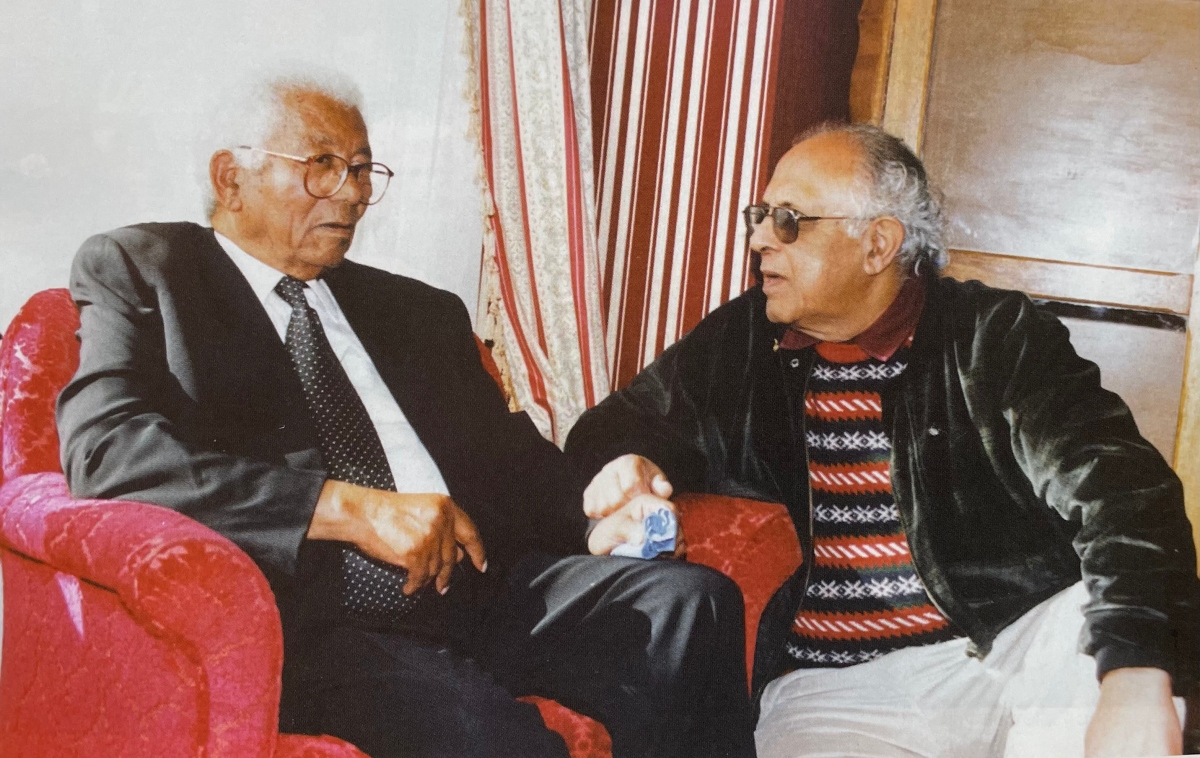

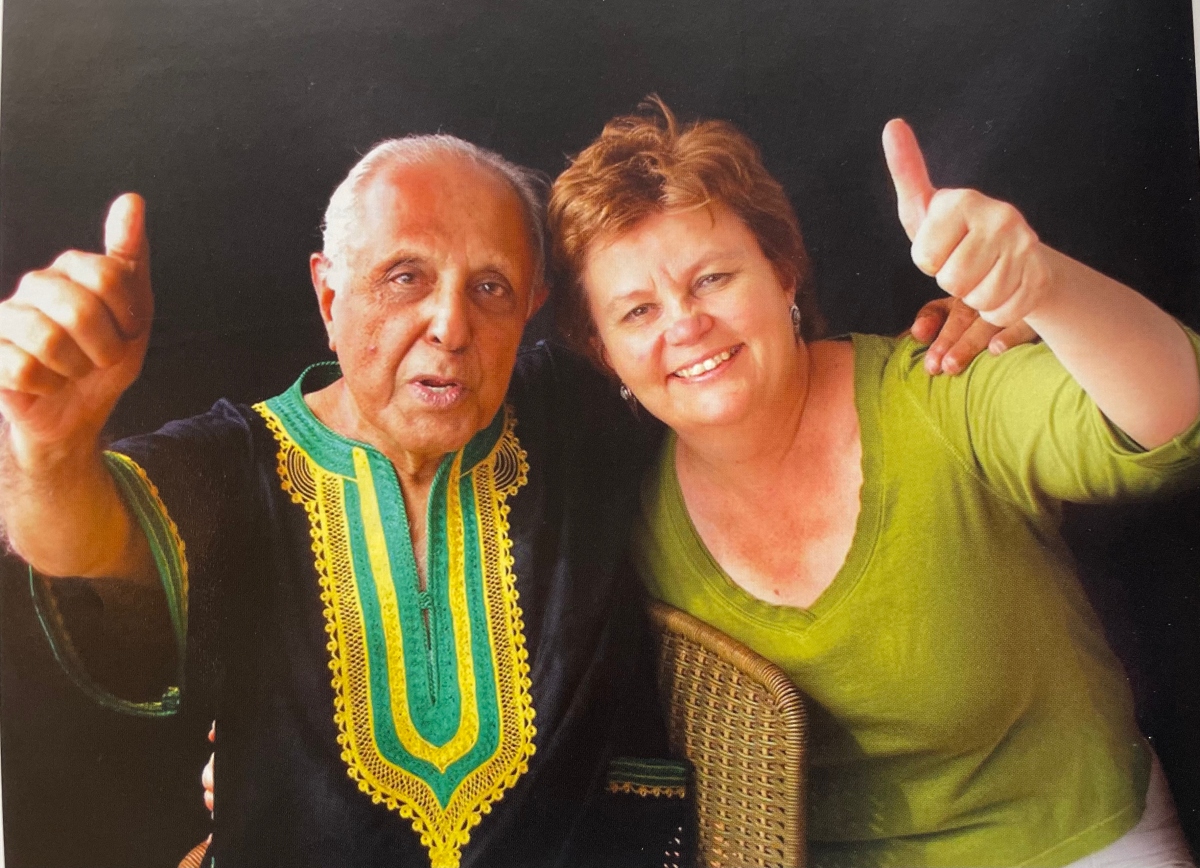

Kathrada (right) regarded Walter Sisulu, a stalwart of the African National Congress, as his 'father'. Photo courtesy: Ahmed Kathrada Foundation

A communist ‘satyagrahi’ since the age of 12

Kathrada (1929-2017), a person of Indian origin in South Africa – his Bohra Muslim parents hailed from the village of Lachpur in Gujarat – was a towering leader of the anti-apartheid movement. He was one of Nelson Mandela’s closest comrades. In terms of struggle and sacrifice, he almost equals the globally revered icon of South Africans’ epic fight against over three centuries of oppressive white minority rule. He spent 26 years in apartheid prisons – that is, just one year less in incarceration than his leader. For 18 years, he was a jail-mate of Mandela in the notorious apartheid prison on Robben Island near Cape Town. In the remaining six years in Pollsmoor Prison, too, Mandela and he were companions.

One of the heroes of the revolution along with Mandela, Sisulu and Oliver Tambo (who served as the ANC President from 1967 to 1991), he was also a highly respected intellectual and writer. His Letters from Robben Island (1999) and his Memoirs (2004) are among the finest chronicles of the battle against tyrannical white rule.

Kathrada began his political activism at the tender age of 12 – as a member of the Young Communist League of South Africa. “From the moment I became involved in politics as a schoolboy,” he would write many years later, “I realised that unacceptable as my own circumstances were, the lot of my African colleagues and leaders — Mandela, Tutu, Sisulu, Tambo, Mbeki — who would become household names, was infinitely worse.”

His childhood hero was Dr Yusuf Dadoo, a respected leader in the Indian community. Though a communist, Dadoo accepted Mahatma Gandhi “as our guide and mentor”. Gandhi, who lived in South Africa for 21 years (1893-1914), had started the non-violent satyagraha or passive resistance in 1906 against laws that discriminated against people of Indian origin. Mandela, Sisulu and others in the African National Congress were deeply influenced by Gandhi’s non-violent struggle in India. (The name of ANC itself was inspired by INC, the Indian National Congress.)

When Kathrada was 17, he was arrested for the first time for his participation in “passive resistance” against the “Ghetto Act” (Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representative Act), which segregated the Indian community from others. For some time, he worked as a journalist with The Passive Resistor, a newspaper edited by Ismail “Chota” Meer, a brave leader of the South African Indian Congress. In 1943, he collected funds for the Bengal famine relief. More about Meer and his wife Fatima Meer a little later.

Also Read: Gandhi's Ideas Against Use of Violence to Achieve Political Objectives Ring True Today

Agit-prop activities of the ‘Picasso Club’

The savagery of the Second World War made the young idealist in Kathrada a passionate participant in the anti-war campaign of the Non-European United Front. He writes in his memoirs: “The atrocities and carnage of the Second World War, the premeditated cruelty that it exposed us to, encapsulates the great moral tragedy of the twentieth century.”

This was the time when he was influenced by left-leaning singers, poets and artists like Paul Robeson, Pablo Neruda and Pablo Picasso. During the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign, Kathrada and some of his friends formed what became known as the “Picasso Club” in Johannesburg. He had probably read Picasso’s article, "Why I became a communist" (1945), in which the renowned painter wrote:

"My joining the Communist Party is a logical step in my life. Through design and color, I have tried to penetrate deeper into a knowledge of the world and of men so that this knowledge might free us. In my own ways I have always said what I considered most true, most just and best and, therefore, most beautiful. But during the oppression and the insurrection I felt that that was not enough, that I had to fight not only with painting but with my whole being…I have become a Communist because our party strives more than any other to know and to build the world, to make men clearer thinkers, more free and more happy."

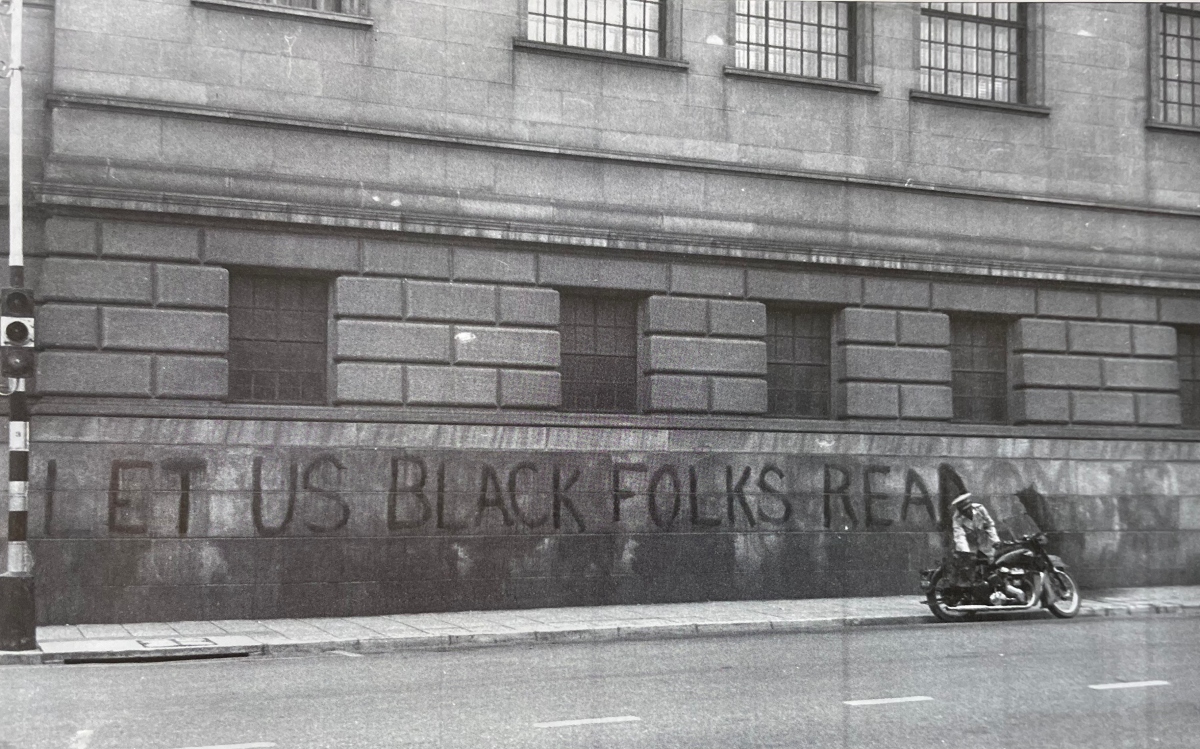

Besides distribution of pamphlets, and putting up posters, the Picasso Club took to political graffiti. One of their slogans that caught the attention of both the public and the authorities was “Let Us Black Folks Read” along the walls of the Johannesburg Public Library, which was for the exclusive use of whites. The municipality erased it. After some days, Kathrada and friends returned to the wall and painted a new slogan that said, ‘We Black Folks Ain’t Reading Yet!’

The slogan painted by the Picasso Club on the walls of a Whites-only library in Johannesburg. Photo courtesy: Ahmed Kathrada Foundation

He marched fearlessly to the prison in Robben Island

Kathrada was jailed 18 times. The last was in 1964, when he was sentenced to life imprisonment in the Rivonia Trial, along with Mandela, Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and other ANC freedom fighters. Incidentally, Mandela, Sisulu and Kathrada are the only three leaders who appeared in the three major trials that form inspiring chapters in the history of the anti-apartheid movement: the Defiance Campaign (1952), Treason Trial (1956-1961) and the Rivonia Trial (1964).

Kathrada was fearless in the advocacy of his principles. For proof, read some of the answers Kathrada gave in his cross-examination at the infamous Rivonia Trial, which is regarded as “the trial that changed South Africa”.

Q: Did you have confidence in those irresponsible leaders of the ANC?

A: I have said that I regard the leadership of the ANC as responsible. I have the fullest admiration for their courage.

Q: You are a member of the Communist Party?

A: I am.

Q: Whose aim and object is to secure freedom for what you call the oppressed people of this country?

A: For what are the oppressed people in this country.

Q: Which involves the overthrow of the government of South Africa?

A: That is so.

Q: By force and violence if necessary?

A: When and if necessary.

Kathrada knew the price he would have to pay for his fearlessness. Prison became his home for the next 26 years, 3 months and 4 days – 9,593 days. After he had served some years in jail, the apartheid government offered to release him – but not other black leaders of the ANC. He refused the offer, saying, “I do not want to be freed alone. All my comrades should be released.”

Last month, I visited Robben Island near Cape Town. Desolate and dreary, its very location makes it look far away from civilisation. Even in prison, the apartheid regime enforced discrimination. Life was harsher for blacks than for Indians and Coloured people.

“If I had to use a single word to define life on Robben Island, it would be ‘cold’,” Kathrada writes in his memoirs. “Cold food, cold showers, cold winters, cold wind coming in off the sea, cold warders, cold cells, cold comfort…Contact of any kind with the outside world was minimal…In all the years I spent on Robben Island, I only once looked up at the night sky from outside my cell. It was on the night of the earthquake, when all our cells were unlocked and we were moved outside into the courtyard.” During daytime, prisoners had to do hard physical labour.

Prison life steeled his relationship with the two leaders he admired the most. “In half a century of knowing Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu, I came to know one sure thing: it is impossible to speak of the one without mentioning the other. Two distinct and unique individuals, these two struggle leaders were inextricably bound by their foresight, courage, wisdom and shared experiences.”

He narrates an interesting fact about how he, Sisulu and other prison mates helped Mandela write his autobiography on Robben Island, with a plan to have it published for his 60th birthday in 1978. Mac Maharaj, a senior ANC leader kept in the same prison, was due to be released in December 1976. He was tasked with smuggling the manuscript out. Mandela began working on the manuscript in January 1976. But, as Kathrada writes, it was a risky plan.

“Chronicling Mandela’s life was illegal and dangerous. Discovery would result in harsh collective punishment…knowledge of it was to be limited to those directly involved. Because most of the writing would have to be done at night, Mandela feigned illness and was excused from the daily work schedule. He slept for a few hours while the cellblock was deserted and wrote deep into the night…Early morning he would give Walter and me the written pages for comment. The final draft was then transferred to sheets of rice paper by Mac Maharaj and Laloo Chiba in miniscule script… Madiba’s originals were rolled up inside empty cocoa canisters and buried in our garden.” (Madiba is a title of respect for Mandela, deriving from his Xhosa clan name.)

Although Mac Maharaj successfully managed to smuggle the manuscript, it could not be published for Mandela’s 60th birthday. The efforts, however, were not fruitless. The manuscript formed the basis of his internationally celebrated autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, published in 1994.

Mandela’s comrade, friend, advisor

Kathrada was released in 1989, just four months before Mandela. One of his abiding interests after his release was Robben Island. Knowing this, Mandela, who became South Africa’s first democratically elected president in 1994, appointed him as the chairman of the Robben Island Museum Council in 1997. Designed with a keen focus on both history and aesthetics, it quickly earned recognition by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. It has now become a must-see place for foreign tourists coming to South Africa. The museum prominently displays Kathrada’s wise words that express its raison d'etre:

“While we will not forget the brutality of apartheid, we will not want Robben Island to be a monument of our hardship and suffering. We would want it to be a triumph of the human spirit against the forces of evil, a triumph of wisdom and largeness of Spirit against small minds and pettiness; a triumph of courage and determination over human frailty and weakness; a triumph of the new South Africa over the old.”

After the triumph of the struggle against apartheid, and the installation of the ANC government, some extreme left-wing black activists started criticising Mandela’s legacy and his vision of South Africa as a “rainbow nation” in which the whites too had an equal place. He had famously said, “I am opposed to white oppression. But I am also opposed to black oppression.” These extremists were exploiting the anger among poor black Africans, who suffered from underdevelopment and lack of economic opportunities. What Kathrada said about this situation, in an interview to National Public Radio (NPR) in the US a few months before his death, is a testimony to his wisdom.

"Anger, revenge, are negative emotions. If one harbors those emotions, you suffer more. And that is where our very progressive policy of forgiveness [came from], in which the ANC started with the transformation from apartheid to democracy – forgive. Don't harbor hatred and revenge.”

He made another perceptive observations about whites in Africa. "We live in a South Africa [where], unlike other colonial countries where the colonists went home after freedom, our oppressors were South Africans, born and bred in South Africa. And not a few thousand, but a few million. So we had to get our people to understand that these are not a few thousand that you can drown in the sea."

Kathrada also played a key role in the establishment of the Nelson Mandela Foundation in Johannesburg in 1999. In his 'Foreword' to Kathrada’s autobiography, Mandela writes: “Ahmed has been so much part of my life over such a long period that it is inconceivable that I could allow him to write his memoirs without my contributing something. Our stories have become so interwoven that the telling of one without the voice of the other being heard somewhere would have led to an incomplete narrative.”

The two comrades addressed each other affectionately as ‘Madala’ or old man. Mandela’s death on December 5, 2013 was a profound personal loss for Kathrada. In a moving eulogy, he said:

“Madala, while we may be drowned in sorrow and grief, we must be proud and grateful that after the long walk paved with obstacles and suffering, we can salute you as a fighter for freedom in the end. Farewell, my dear brother, my mentor, my leader. With all the energy and determination at our command, we pledge to join the people of South Africa to perpetuate your ideals. When Walter died, I lost a father, and now I have lost a brother. My life is in a void and I don’t know who to turn to.”

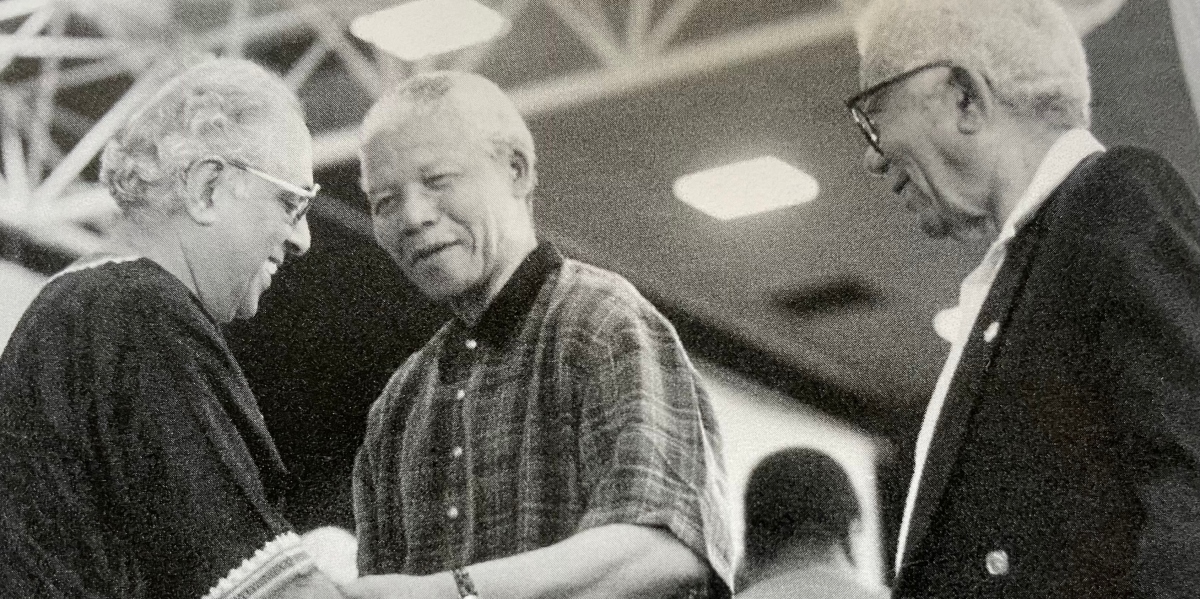

'Heroes of Freedom': Mandela , 27 years in jail with Kathrada, 26 years in jail, and Sisulu, 25 years in jail. Photo courtesy: Ahmed Kathrada Foundation

The umbilical cord connecting Gandhi and the anti-apartheid struggle

In recent years, some academics and black activists in Africa have painted Gandhi as a racist. They deny any Gandhian influence over the struggle against apartheid. Therefore, I would like to add here a few lines about Kathrada’s editor, Ismail Meer, and his illustrious wife Fatima Meer, both of whom were Mandela’s close associates in the anti-apartheid movement. They were also Kathrada’s lifelong friends. This digression is necessary to recall the now largely forgotten, and even falsely contested, umbilical cord that connected the anti-racist struggle of Indians under Gandhi’s leadership in the early part of the 20th century and the subsequent larger struggle of the ANC against apartheid.

Fatima Meer, acclaimed Gandhian scholar and anti-apartheid activist, authored Nalson Mandela's authorised biography. Photo: By arrangement

Fatima’s father, Moosa Meer, a migrant from Gujarat, was a trusted associate of both Gandhi and Mandela. He was the editor of Indian Views, a newspaper that opposed the white-minority government. Fatima and Ismail Meer played a pivotal role in cementing the relationship between the Indian community, ANC, and important black leaders such as Mandela, Sisulu, Tambo and Chief Albert Luthuli (who headed the ANC from 1952 to 1967, and was awarded the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in leading the non-violent anti-apartheid movement).

As Ismail Meer, who was greatly influenced by the writings of Jawaharlal Nehru, has recorded in his autobiography, A Fortunate Man, “It was the Passive Resistance Campaign of 1946 by Indian South Africans against the Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act that laid the seed for the 1952 Defiance Campaign (the largest scale non-violent resistance ever seen in South Africa and the first campaign pursued jointly by all racial groups under the leadership of the ANC and the South African Indian Congress); the 1955 Congress of the People (which brought together the African National Congress, the South African Indian Congress, the South African Coloured People’s Congress, the South African Congress of Democrats and the South African Congress of Trade Unions into a non-racial united front); the birth of the Freedom Charter (which visualised the abolition of all racial discrimination and the granting of equal rights to all, with its electrifying slogan, 'Freedom in Our Lifetime’); and the Treason Trial of 1956 (in which 156 people, including Mandela, were arrested and subsequently found not guilty; however, some of the defendants, including Mandela, Sisulu and Kathrada were later convicted in the Rivonia Trial in 1964)."

Fatima Meer (1928-2010) herself forms another close and proud link between Indians’ and black Africans’ struggle against racism. She was imprisoned for working closely with Winnie Mandela (Nelson Mandela’s first wife) in the Black Women’s Federation. She authored Mandela’s authorised and internationally acclaimed biography, Higher Than Hope. She was also a renowned Gandhian scholar-activist. She gives a perceptive description of how South Africa transformed Gandhi, in her book Apprenticeship of a Mahatma – A Biography of M.K. Gandhi:

“On the 18th of July, 1914, twenty-one years after his arrival, Mohan accompanied by his family, left South Africa. He had come to the country as a young man of twenty-three, a semi-Englishman. His host, on meeting him, had wondered how he could afford to keep such an expensive-looking dandy. His tastes had continued to be expensive for a while, but they had changed through the intermingling of thoughts and experiences. Now he left the country bearing all the signs of a man who would soon be recognised as a saint — As Christ became the Saviour, Muhammed the Prophet, Gautama the Buddha, the little boy frightened of the dark became the Mahatma and paid the price of all Mahatmas."

I had the privilege of meeting her in Durban, when I accompanied Prime Minister Vajpayee to attend the Non-Aligned Movement Summit in 1998. The precious gift she presented to me at her home – South African Gandhi, a 1200-page book edited by her – has preserved for me memories of this courageous and gentle-faced fighter for human freedom and dignity.

Kathrada in his memoirs writes with deep affection about Ismail and Fatima Meer. “The passing of Ismail Meer on 1 May 2000 not only left a vacuum in my life but, as I wrote to his widow Fatima and their family, ‘left South Africa poorer. May the example of his life serve to nourish the ideas and practices for which he devoted so much of his time and energy.”

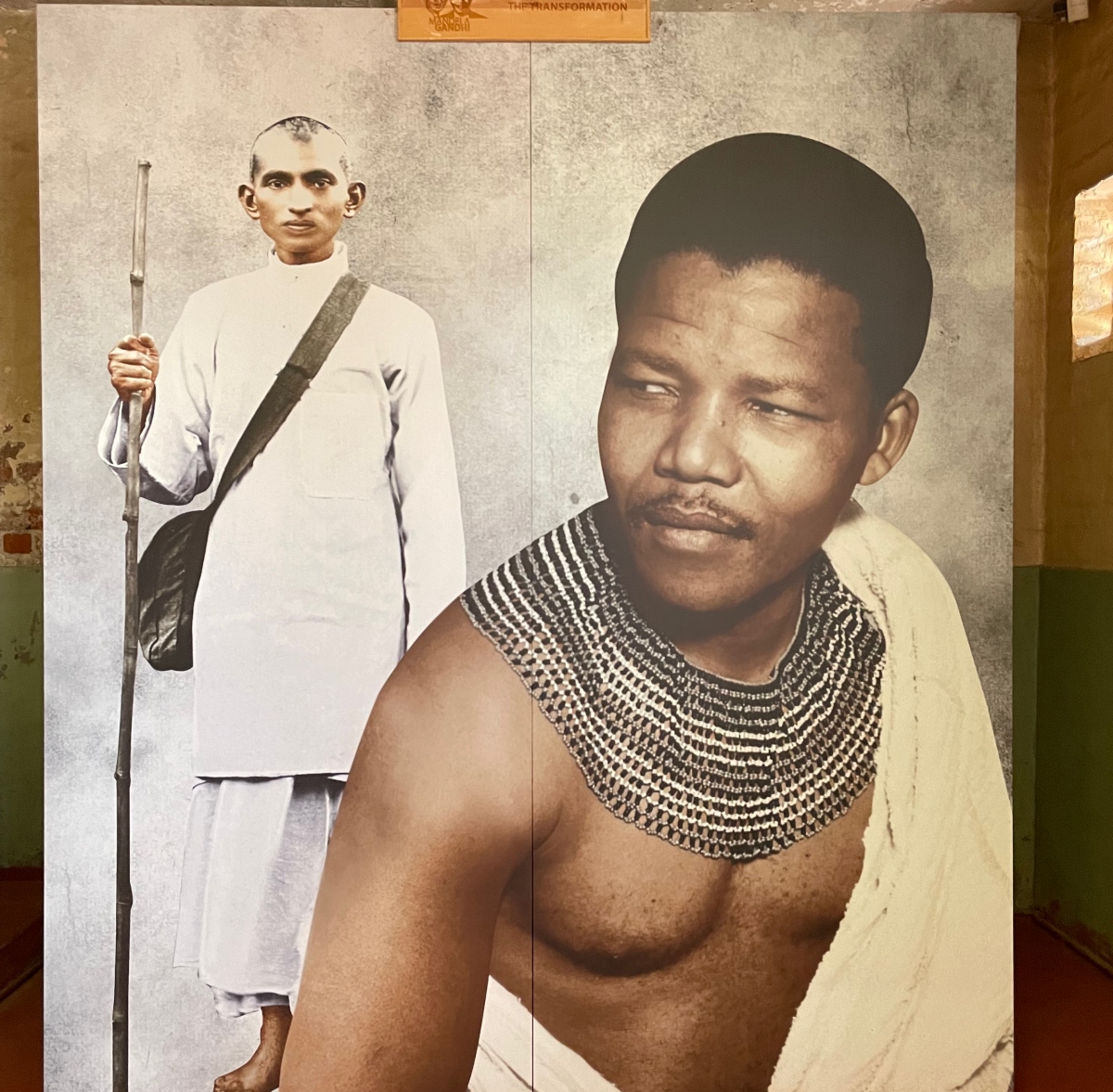

Mahatma Gandhi's nonviolent satyagraha had a profound influence on Nelson Mandela. An exhibit at Mandela-Gandhi Museum in Johannesburg. Photo: Sudheendra Kulkarni

Embodiment of modesty, humility and incorruptibility

Kathrada personified not only courage but also modesty and humility, qualities that come to those who have walked in the shadow of death and are transformed by the pain of prolonged jail life. He never hankered after power. After the success of the revolution in 1994, President Mandela offered him a ministerial position in his Cabinet, which he refused. Instead, he chose to serve Mandela as his Parliamentary Counselor. Both his leader and he retired from state office in 1999. Thereafter, till the end of his life he continued to be an influential voice committed to taking South Africa along the path of non-racialism, non-sexism, and pro-poor governance free of corruption.

Such was his moral courage that, a year before his death on March 28, 2017, he publicly criticised South Africa’s then President Jacob Zuma (who belonged to the African National Congress) when the latter got embroiled in corruption scandals. Two Indian businessmen, Rajesh and Atul Gupta, who were extremely close to Zuma, were the kingpins in these scandals. Kathrada wrote an open letter asking Zuma to resign: “Dear Comrade President, don’t you think your continued stay as president will only serve to deepen the crisis of confidence in the government of the country?”

Zuma was ultimately forced to resign in 2018, and was also arrested in June 2021. His arrest sparked violent attacks on the Indian community in Phoenix and other parts of the country. Before Kathrada died, he told his wife and a close colleague to communicate a message to President Zuma to stay away from the funeral. In accordance with his wishes, he was buried with Islamic rites. Also, in line with his belief in multi-religious unity, his funeral commenced with Muslim, Christian, Hindu and Jewish prayers.

This is not surprising because Kathrada had friends and comrades who belonged to different religions. His closest friend, also his jail mate, was Ishwarlal Laloo Chiba. After his release from prison, he married Barbara Hogan, who had herself been sentenced to ten years of imprisonment in the early 1980s for her participation in the anti-apartheid struggle. “I support the freedom of people to worship as they see fit, but I believe in a secular state,” he writes in his memoirs.

Ahmed Katharda with his wife Barbara Hogan, who was jailed for ten years for her participation in the anti-apartheid struggle. Photo courtesy: Ahmed Kathrada Foundation

India’s cultural pluralism fascinated him

Kathrada’s autobiography is replete with praise for Gandhi, Nehru and India in general. He especially admired India’s plural culture. “My own views on multiculturism,” he wrote, “are best summed up in a passage by Gandhi: ‘I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any.’”

Throughout his prison term he received letters from friends who had travelled to India. “Without exception, they had been profoundly impressed and excited by what they found there. I could not understand what they found so pleasant. Born and educated in South Africa, they had all grown up, as I did, with a mental picture of a vast country besieged by famine, malnutrition, disease, undesirable poverty, communal strife, lawlessness, corruption and filth.”

He then writes: “It was only when I went to India myself, after my release, that I understood the enchantment, and realised that the picture sketched by the media in the West was grievously distorted, with so much emphasis on the negative aspects of the country that we were ignorant of the hospitality, warmth, simplicity, cultural richness and beautiful architecture of the subcontinent. Unfortunately, Third World countries all too frequently fall victim to slanted reporting that relies on sensationalism and unfavourable news at the expense of the positive.”

My visit to Ahmed Kathrada Foundation in Johannesburg

We Indians should keep alive the memory of this great freedom fighter not only because he was of Indian origin, not only because he was Mandela’s alter ego, but for another reason that is important for both contemporary India and contemporary South Africa. And I came to know about this reason when I visited the headquarters of the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation in Lenasia, Johannesburg, which is devotedly carrying forward his mission to “deepen non-racialism and to promote the values, rights and principles enshrined in the Freedom Charter and the Constitution of South Africa”.

One a cool morning last month I drove from my hotel in Sandton, the main business district of Johannesburg, to Lenasia, some 40 kilometers away on the city’s outskirts. The apartheid regime created this township exclusively for the Indian community in the days of racial segregation. Even today a majority of its residents are people of Indian origin. Although they have been living in South Africa for many generations, the streets are still named after Kashmir, Lucknow, Bombay, Bangalore, Mahanadi and so on.

The office of the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation was buzzing with activity – young volunteers, both black and Indian, female and male, were immersed in their tasks. It has 30 youth clubs across the country and aims to create 100 of them within the next few years. Here I met two leading office-bearers of the Foundation – Neeshan Balton, its executive director, and Ismail Vadi, its board member, a former member of parliament and provincial minister. They told me that the African National Congress, which successfully led the struggle against apartheid, is no longer what it was in the days of Mandela and Kathrada. “ANC is faction-ridden. Economy is not in a good condition, especially for the poor. Youth unemployment is as high as 50%. There is racial tension between Indian and African communities. Moreover, the corruption scandal involving the Gupta family and former President Zuma has badly damaged the reputation of Indians. Therefore, we need to build a new generation of leaders committed to the better values of the liberation movement – integrity, honesty, welfare of all South Africans without any distinction or discrimination. We cannot live in the past.”

Religious leaders carrying South African flags walk near a looted shopping mall as the country deployed the army to quell unrest linked to the jailing of former South African President Jacob Zuma, in Vosloorus, South Africa, July 14, 2021. Photo: Reuters/Siphiwe Sibeko/File Photo

If this is the contemporary South African situation that necessitates preservation of the legacy of noble souls like Ahmed Kathrada, there is also something happening in contemporary India that has created the same need. “Unfortunately, the politics of communal polarisation in India is creating divisions between Hindus and Muslims in the Indian community in South Africa,” Balton and Vadi said to me. “Some Hindutva forces are active here. The Muslim community has become inward-looking. Its Muslim identity has become stronger and its Indian identity, especially among the youth, is becoming weaker.”

It was painful to hear this because unity of the Indian community across religious, caste and linguistic lines was one of the proud achievements during Gandhi’s time in South Africa and the subsequent period of the anti-apartheid movement under Mandela’s leadership. Surely, the Indian government, India’s political parties (especially the BJP), our religious-cultural-business organisations, our Gandhian organisations and all other civil society organisations have a major responsibility to cement the cracks that have surfaced both between black Africans and the Indian community and also within the Indian community itself.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi met Ahmed Kathrada during his visit to South Africa in July 2016, and tweeted: “Dr. Ahmed Kathrada is a hero and a great source of inspiration. So delighted to meet him.” In January 2017, the Government of India donated two million rands (about Rs 90 lakh) to Ahmed Kathrada Foundation “in recognition of the important role it plays in South Africa and to support the Foundation in fulfilling its activities”.

Dr. Ahmed Kathrada is a hero & a great source of inspiration.So delighted to meet him. pic.twitter.com/dnPl5UzDzQ

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) July 9, 2016

This gesture was laudable. But certainly more needs to be done, especially in India, to preserve the memory of this great Indian-South African. Why not an Ahmed Kathrada University in Gujarat? Why not a Gandhi-Mandela Museum for India-Africa Friendship with a gallery devoted to Kathrada? Why not an award in his name to honour those South Africans rendering great service in furtherance of the common ideals of India and South Africa? Why not invitation to members of the youth clubs of Ahmed Kathrada Foundation to visit India – and reciprocal visits by India’s youth leaders? Letting his name go into oblivion in India would be a disservice to the ideals that animated our own freedom movement and that ought to guide our nation’s future.

Sudheendra Kulkarni served as an aide to former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and is the founder of the ‘Forum for a New South Asia – Powered by India-Pakistan-China Cooperation’. He is also the founder of Gandhi-Mandela Centre for India-Africa Friendship. He is the author of Music of the Spinning Wheel: Mahatma Gandhi’s Manifesto for the Internet Age. He tweets @SudheenKulkarni.

This article went live on December sixteenth, two thousand twenty two, at forty minutes past one in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.