Aurangzeb's Afterlife and the Chhaava-fication of Indian History

An emperor who died in 1707, and his rather modest grave, have become the subject of heated debate, tensions and even an excuse for violence in 2025. Aurangzeb has been used as an emotive issue by the Hindu Right for decades now, before which the British colonials too found him to be an easy villain. The Wire's Jahnavi Sen speaks to historian Dr Ruchika Sharma and author Parvati Sharma about the Mughal ruler's life and policies, the political use of his figure to try and vilify Muslims, and the growth of propaganda claiming to be history.

You can read a full transcript of their conversation below.

§

Jahnavi Sen: Hello, and welcome to The Wire.

I'm Jahnavi Sen, and we're here today to talk about why an emperor who died in 1707, and his rather modest grave, have become the subject of heated debate, tensions, and even an excuse for violence in 2025. We're talking, of course, about Aurangzeb, and how calls for the destruction of his tomb in Aurangabad, which has been renamed Sambhaji Nagar, led to violence in Nagpur.

Aurangzeb has been used as an emotive issue by the Hindu right for decades now, of course by the BJP, but also before that by the Shiv Sena in Maharashtra. The most recent trigger for his name being dragged into contemporary politics is a film, Chhava, which follows the rule of Maratha king Sambhaji, Shivaji's son, and his capture, torture, and execution by the Mughals under Aurangzeb.

Bringing up Aurangzeb, or other rulers who have been portrayed as villains, does not seem to be about history for the Hindu right. Instead, it's an attempt to hold Muslims in today's India responsible for the wrongdoings of these kings. For that attempt, it becomes essential to paint history in completely black and white strokes. Some rulers have to be brave, courageous saviours, while others are evil, cruel, and out to destroy Hindus.

Maharashtra chief minister Devendra Fadnavis had in 2023 referred to those posting positively on social media about Mughal emperor Aurangzeb as ‘Aurangzeb ki aulaad’ or the children of Aurangzeb, and claimed that they were the ones responsible for communal tensions in Kolhapur.

More recently, he has rued the fact that Aurangzeb's tomb is an ASI monument and so can only be removed using legal means. He was responding to his party colleague and MP, Udayanraje Bhosale, who wanted a JCB bulldozer taken to the site immediately. After initially praising Chhava for showing the truth, Fadnavis has also now blamed the movie for the communal violence in Nagpur. Samajwadi Party MLA Abu Azmi, who called Aurangzeb a good administrator and not a cruel leader, was immediately suspended from the state assembly without even being given a chance to make his case.

The portrayal of Mughals as the enemy is not specific to Maharashtra. None other than PM Narendra Modi himself has referred to India's 'thousand years of slavery', claiming that colonialism began much before the British came to India. Streets and areas named after Mughal rulers have been deftly renamed. Chhava is also one among many movies made to push the same kind of black and white history.

To talk about all of this, I have with me today Dr Ruchika Sharma, who is a historian and also runs a YouTube channel to counter misleading historical narratives, and author Parvati Sharma, who has written historical profiles of several Mughal rulers. Thank you both so much for joining me.

If I could start with you, Ruchika. One of the most common refrains we hear when we are talking about Aurangzeb is the thousands of Hindu temples he destroyed during his rule. Now some historians like you have pointed out that A, this number is likely an exaggeration and B, it seems like his motivations were more mixed. They could have been political, because there were other times during his rule in which he gave grants to temples.

Could you talk a little bit about that, his actions and his likely motivations?

Ruchika Sharma: Absolutely. I think 100% the thousand mandir destruction bit is a complete exaggeration. It is hyperbolic. And I think the entire idea, as you very correctly summarised in your introduction, is to hype up the idea that the Muslim rulers, especially like Aurangzeb, were very brutal. We have a proper calculation done by Richard Eaton in his Temple Desecration – this very fascinating essay that he has written, which is I think 100-page long, it is almost like a booklet. And I would certainly ask all of your viewers to read it. It is a brilliant book and really needed in times like these. And in his calculation, from 1192 to 1707, there are only 80 temples which were demolished, out of which Aurangzeb is responsible for around 10 temples. And that is the number that we have. So, from 1,000, it comes down to 10.

But if you look at the list of temples that he has patronised and the non-Muslim saints that he has patronised, the list is much longer than 10. And this is something that is completely not talked about. In fact, for me as a historian as well, this was a much later learning because this is what we are always taught, even in schools, and even in undergrad history, etc., very rarely do we talk about or do students know that Aurangzeb actually had patronised temples and he had given grants. And we have inscriptional records, you know, like ASI, 18, 19th century reports of the colonial people. We have records from temples like say Gopinath Temple, and we have an inscription over there, dated 1699, by this person called Nauniddh Rai, who says that I have got this temple built and the temple tank built, and the money was given by Aurangzeb. And it is a Shiv temple. And fascinatingly inscription says that Aurangzeb gave the grant so that Aurangzeb's reign and Shiv's austerity can prosper forever. It is fascinating that both of them are used in the same sentence, almost as equal. So, it is a fascinating inscription.

We have a massive farmaan in Chitrakoot, which is very near to Ayodhya. And the temple is called Balaji Temple. And the grant was given to the mahant of that time, called Mahant Balak Das Nirvani. The farmaan is absolutely genuine, because once it was discovered, it was then ratified by Irfan Habib, Shireen Moosvi, Athar Ali, who are the stalwarts of Indian history. And they all consider it to be an authentic Aurangzebi farmaan. And it goes on to detail how many bighas of land is going to be given. And if you look at the temple also, it is built in this very char-chala style roof, which is basically this style of architecture which started from Jahangir's reign onwards, where you would build what is called as the Bangla roof as well, which even Noor Jehan had for her father, the tomb of I'timad-ud-Daulah in Agra. So, you have something very similar being built over there. It is gorgeous in itself as a temple.

Then you have a Dauji Maharaj temple in Mathura. It says the nakkarkhana in the temple was built by Aurangzeb. There is a Kedarnath temple associated with the Kumar Swami Math, which was rebuilt by Aurangzeb because it required repairs. And then there are a list of saints that he patronised as well. So you have Mangaldas Bairagi, Garibnath Sanyasi who fascinatingly received a khilat, which is a very fascinating thing that happened in the Mughal Empire, which is like the set of robes that the emperor wears. And it has eight parts of it. So, you will have the belt, you will have the turban, you know, so on and so forth. And if all of it or parts of it are given to you, it is considered to be a huge honour because it is once worn by the emperor. So, it is imbued with his benediction. If it is given to you it means you are really held in high regard and you are sharing in his benediction. He was given the Khilat, right. Then we have Ram Jeevan Gosai, who was given the Beni Madho Ghat, the grant of Beni Madho Ghat.

We have these two very good examples. One is, of course, in Guwahati, we have this temple called the Umananth Temple. And the inscription, I think, is still there. This grant was given to the priest of the Umananth Temple called Saudaman Brahman. When Aurangzeb attacked Assam, the Ahom Rajas were patronising this particular temple and they were giving grants to Saudaman Brahman. But Aurangzeb, instead of revoking those grants, said we are going to continue these grants for you, but I am going to give you additional grants as well. So, it is a very fascinating display of what we today call this, quote unquote, ‘Aurangzebi soch’ and the ‘Aurangzebi mindset’, which we generally tend to think that he was a temple destroyer, etc. But no, you have this. He gave protection to this saint in Banaras called Bhagwant Gosai. His son wrote to Aurangzeb saying they are not letting my father do his prayers in peace and I need you to intervene. So he did intervene and he issued a farmaan saying, if anybody upsets Bhagwant Gosai, then you are an enemy of the crown. It is a huge thing that he is coming out in defence when the popular idea today is that he was probably the reason why the saints were not able to practice their daily rituals. But that is clearly not the case in a lot of examples.

The Mahakaal temple, probably the most famous grant that he has given, we have farmans of the Malvas of Subedar, which say that there is this tradition in the Mahakaal temple, which is that the Nandandeep – this particular light that needs to be always lit for Shiv – must be always lit. Therefore, the Malvas of Subedar under the auspices of Aurangzeb are giving grants of four sayars of ghee. So, every time you need four sayars of ghee, it will come from the land grant which has been given to you, the taxes will go to you.

So, we have so many of these examples. I think this has happened like four, five years ago, when somebody had put an RTI to the NCERT, on this particular statement that the NCERT had in its book. And it is one of those very good books, the JNU authors, professors, etc. have edited it and all of that, which said that if Aurangzeb broke temples, he also gave grants to temples. And NCERT wrote back saying we do not have records of Aurangzeb [giving grants], which was completely bewildering. But he did give grants to temples. I do not want to sort of drag the whole thing, but I have even more examples of temples that he gave grants to. There is a bigger list.

So, just to sum up, I think the reason why this happens is, I will certainly come to the colonial bit, because I think they are the ones who start this whole drama. But taking it to this level is certainly the right-wing's doing today, wherein you cannot even say that, no, but there are good things that Aurangzeb also did. He had a different policy, he had Rajputs under him, 33%, so on and so forth. Now, there is a huge list of things that I can talk about, which can be considered as, quote unquote, ‘good policies’. I would not do it as a historian, because I think that is very juvenile to do good policies and bad policies. But in the popular sphere they are his good policies, that he was benevolent, and he did this and that. But nobody talks about that. And if somebody wants to talk about it, I think they suspend him and all of that. I do not know what was Abu Azmi's motivation to do this. But I think it is very important that we talk about both sides, because so far we have been telling an incomplete history of Aurangzeb in the public sphere.

Members of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal stage a protest demanding the removal of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb's tomb, at Aazad Maidan in Mumbai, Monday, March 17, 2025. Photo: PTI/Shashank Parade

Jahnavi: Another thing that people say about him is about the brutality of his rule. But if we were to look at it in medieval India, how different was Aurangzeb's rule in terms of the brutality alone, compared to both other Mughal rulers and also other rulers at the time in different parts of the other kingdoms?

Parvati Sharma: I do not know if I can answer this. I think Ruchika may have more details on Aurangzeb's part, I am not sure if I am qualified to be able to compare between him and others. But I would say that rulers tended to be brutal and authoritarian. There was a great deal of concentration of power, but also a great deal of power that was delegated.

There were times in which warfare was common, executions were common. I mean, it was a different time.

But that said, perhaps just to talk a little bit about why we are even contrasting or wanting to find, as I think Ruchika was hinting at, why are we having to feel the need to advocate for or say that perhaps you are more brutal, less brutal. And we are feeling the need to do this, partly, because I think something funny is happening in the way that we are engaging with history. I mean, there are many, many reasons for it, the colonial period that you hinted at, the British needed a bad guy. And the immediate predecessors to the British were the Mughals. Mughals had huge legitimacy, even in their most decrepit, crumbling when the Mughal emperor was a husk, he was still highly legitimate. The Shah Alam, who was after the Battle of Buxar, there is nothing to him, there is no power whatsoever. He is legitimate even in the eyes of the Marathas, who give him nominal suzerainty. They accept robes and other sort of symbols of rule from him. A century later, Bahadur Shah Zafar is the focal point of the 1857 mutiny. And in this case, it is the people who come to him, the sepahis who come to him, not the elite. And as a result, the colonial state has a great deal invested in trying to get rid of them. Of all the princely states that we had, I think almost all of them continue to exist, even today. [But] the Mughals are disappeared from history. And then you need to delegitimise them, which they do by suggesting that they were autocratic, despotic, dissolute. And of course, Aurangzeb is the best villain that you can find.

Later on, perhaps even in nationalist Indian history, when the nation is being built, again, you need a kind of counter, right? So you are building a new secular state, and you build it against, you need a communal villain, and who better than Aurangzeb? Which is why even when we were studying history, like you said, Aurangzeb is the one villain that we have in our history, which is otherwise comprised of basically good people. Everyone from the Harappans onwards is working to create the Indian state, except this one chap.

And then now what's happening is that we have a situation that all of these things have been going on in our consciousness, subconsciousness for decades, and we have a situation where we have the study of history becoming increasingly urgent, I mean, it's obsessive. And I'm talking about popular history, social media history, WhatsApp history – some of it is very good, and you [Ruchika] do great work, some of it is very bad – but it's there and a huge amount of people are consuming it. So at one level, there is a massive amount of obsessive interest in wanting to know the past, but secondly, there's this strange idea that historians need to be unbiased. Whichever side you are on, the other side is biased, and this side is unbiased, without any examination of the fact that all historians are biased, history written by human beings. And at the third level, I think perhaps what is happening is that at the academic level, both in schools and in colleges, the study of history is declining. The textbooks are being hollowed out, students are not enrolling to study, I know of at least one history department that is in imminent danger of being shut down. So what we are getting is an obsessive interest in knowing things in facts, or knowing things in bite-sized instalments of the past, but without being invested or interested in the idea of scepticism, or doubt, which is I think, the main skill of a historian – to question everything. That's the first thing you do, because you have all these sources, you do not go blindly trusting anything.

Therefore, then you are able to get to a point where Aurangzeb must either be good or must be bad, right? We have to either defend him or condemn him, without being able to feel that people contain multitudes, all of us we contain multitudes. So, imagine some 17th century, 18th century emperors invested with this unimaginable amount of power – you're full of contradictions.

Jahnavi: I wanted you to come in on the part about, you know, yes, we've all grown up hearing, particularly about Aurangzeb – whatever facts you may or may not remember, you remember that he reimposed jizya. And like both of you mentioned, this did begin with British colonialism. So, I wanted to talk more about that and also maybe specifically about why he was the one who was so easy to make the one one bad guy.

Ruchika: I think I'll come to the colonial bit later, because I think the fault somewhere also lies with the fact that even till date, history is somewhere down the line still in the colonial mould, right. So, if you look at, for example, this comparison that you were doing with, say, Aurangzeb and vis-a-vis other Mughal rulers, the colonial people had this idea of Akbar being the 'good Muslim' and the epitome of the good Muslim, because he's, quote unquote, ‘secular’. And then Aurangzeb is the bad Muslim, because he's not secular, he's a religious bigot – that's the term that they often use for him.

But if you actually look at the histories of both these, there are a lot of similarities, Akbar started this policy of putting Rajputs in the mansab jagir system. Aurangzeb took it to a new level. So, if it was around 15-20% under Akbar, it was around 33% under Aurangzeb. Two of his best men were both non-Muslims, Mirza Raja Jai Singh and Jaswant Singh. In fact, almost all the wars that he's fought against the Marathas have been fought by Rajputs for him. So this idea that somehow Aurangzeb is the polar opposite of Akbar is not borne out in a lot of his policies.

Jizya is a very interesting example. I think we don't realise how much jizya changed, starting with Akbar, all the way to Aurangzeb. It has a history of its own. I think you can actually tell the history of the Mughal Empire just by telling the history of jizya. It's so interesting. So, Akbar starts off by putting a ban on it around 1562-63, and then he resumes jizya around 1575, and then puts a ban again in 1579.

Now, throughout this, there is a very interesting thing happening between Akbar and the Muslim conservatives in his reign. Initially when he bans it on principle, because

Akbar, credit were due, had a mind of his own. If you read, say, Athar Ali on Akbar and his religious views, you'll see he's a very avant-garde person. He's really ahead of his time. He thinks about why should we do tradition, why should we have taqlid, we should have akhlaq. So he bans it because of his own foresight, thinking that this is a discriminatory tax. He also bans the Hajj tax. But then the Muslim conservatives are not okay with this, because this is a tax that has historical precedence and has always occurred. So he falls out of favour with the Muslim conservatives, but he wants to win them back. So, in 1575, he brings it back. But at the same point of time, he, still cannot garner favours with the Muslim conservatives, because as a ruler, he cannot always follow what the Muslim conservatives want him to do, he is ruling over a vast non-Muslim majority. And he has a lot of policies which might not comply with, quote, unquote, the Sharia.

So when he reimposes it in 1575, he's trying to win them back, but he can't. So in 1579, he puts it back in the bank again, with a very controversial document called the mahzar, in which he declares himself as the mujtahid, which is like the sole interpreter of the Quran. He calls himself Sultan al-Islam, a very fascinating title that nobody had given before him, not even the Khalifas, etc. And then from 1579, all the way till Shah Jahan's reign, jizya is not reimposed. Then Shah Jahan is the first person to reimpose it – usually people think it's Aurangzeb, but Shah Jahan does it. J.F. Richards has a very good thesis on this – Shah Jahan uses Islam as a very interesting factor. A lot of people think Aurangzeb is the person who caused the decline; the decline of Mughal Empire, according to me, started with Jahangir, because he gave over-promotions, he wasn't the most efficient ruler. I think Akbar knew this, which is why he didn't want Jahangir. He wanted the crown to skip a line, he wanted it to go to Khusrau. But anyway, Jahangir sort of sowed the seeds for it.

Then Shah Jahan had to do the damage control. He had to cut down on the sabar ranks and the mansabdar, etc. I won't go into the details. And reimposing jizya is part of that, part of gaining financial capital. And then it's put back, it's banned again. And then Aurangzeb puts it back, reimposes it 10 years after he becomes the king. So that's very important, if he was just doing it because this was something austere, and he was a religious bigot, he would have done it the moment he won Samugarh and he knew that he's now the badshah. But he didn't do that. So this clearly was a financial decision. He also brings back the pilgrimage tax.

The jizya in itself is very interesting – reimpositions and banning and all of that. And Aurangzeb is just one of the part of it. Another thing there – because you mentioned even nationalists thought of Aurangzeb [in a certain way] – so I would like to bring in Nehru and Discovery of India, where he thought that somehow before Aurangzeb, the Mughals had created a culture of cosmopolitanism that Aurangzeb pounced upon. And one thing that comes to mind is his banning of music. But there have been new studies on it, Katherine Butler Schofield has a very good article on it, where she says that there are only two sources that say that he banned music. One is, of course, this very notorious source by Niccolao Manucci, Storia do Mogor, who himself says that a lot of his stuff is based on bazaar gossip. So we are very thankful he's clarified that for us. He's also the person who gave us this salacious gossip of Jahanara (Shah Jahan's daughter) and Shah Jahan being in some incestuous liaison. And then this person called Khafi Khan [who wrote] Muntakhab-al Lubab, they both say that he banned music. Niccolao Manucci says he banned music around 1653, when his lady love Heerabai Zainabadi died, who was a musician. They said he was so distraught that he banned music. But in 1658, Niccolao Manucci himself tells us that when his coronation happened, there was music. And he gave 7,000 rupees to Khushwant Khan Kalwant, who was one of the greatest musicians of his time under Aurangzeb. Then in 1665, Jean-Baptiste de Bernier tells us there was music in Aurangzeb's court. And the lady love of the later half of his life, Udaipuri Bai, was also a musician. So I think this idea that there was a summary ban on music, that he tried to create a culture of hatred – I think it's completely exaggerated. And if you actually look at the details, the devil is in the details, you don't really find it.

I think the British were not interested in the details. If there's one thing that they were not interested in, it's in the [details]. They did a very superficial history of India. And it suited them to have somebody like Aurangzeb, because then they could create the enemy. In the 1857 revolt, as Parvati mentioned, the people who got the maximum punishment were Muslims. They were considered to be the people who had masterminded the 1857 revolt. And the Hindu bankers and merchants, so you had Choonamal and Bhavani Shankar in Delhi, they had funded the British. So they became the friends. And you had a lot of princely states who also did not support the 1857 revolt. So this idea that 'This is basically how Muslims are, they're brutal, they kill us, they rape our women' – so there was this exaggerated idea of how many English women were raped and all of that. And Aurangzeb somehow becomes the face of all of that. He's the person, this is the mindset.

But at the same point in time, the English are also in awe of the Mughal empire. They also want to rule as ruthlessly as they think in their mind that the Mughals did. So therefore, they use them in their architecture, they shift their capital to Delhi because it has the Mughal legacy. So I would think that the British had this very interesting relationship of awe and hatred towards the Mughals. The hatred bit was reserved for people like what they thought was Aurangzeb. So I think in the popular sphere, it starts with these people, the colonial people, sowing the seeds. And then of course, because the Hindu right was then, it was born in the British times. So they have then taken it to multitudes now.

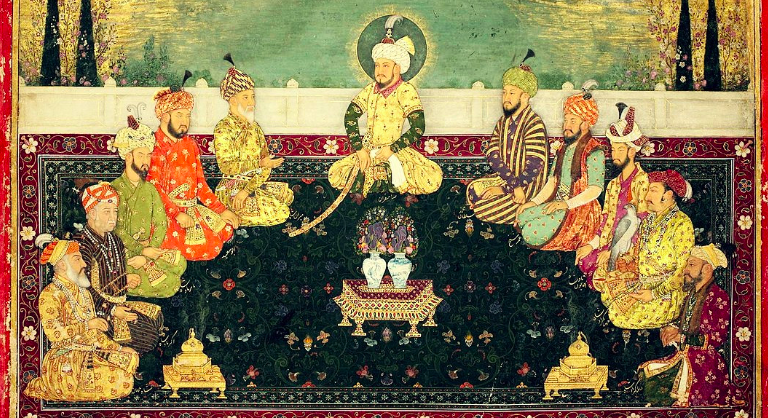

Group portrait of Mughal rulers, from Babur to Aurangzeb, with the Mughal ancestor Timur seated in the middle. On the left: Shah Jahan, Akbar and Babur, with Abu Sa'id of Samarkand and Timur's son, Miran Shah. On the right: Aurangzeb, Jahangir and Humayun, and two of Timur's other offspring Umar Shaykh and Muhammad Sultan. Created c. 1707–12. Photo: CC BY-SA 3.0 igo

Jahnavi: I want to come back to something you were saying about the fascinations with history today and this sudden boom in history telling. A part of that we are seeing in popular culture. The way we started this discussion was around the film Chhaava, and maybe that's the one in recent times that we've seen lead to actual violence on the streets. But there have been films like this that have been coming out at a very rapid pace over the last few years. Parvati, would you define these films as propaganda?

Parvati: Yes. Very much so. Because they are concertedly pushing for a certain

kind of, not just a narrative. A narrative is still one thing, and you can have narratives being created. They are also pushing for a certain kind of demonisation of a particular community. By and large, it tends to be Muslims, but it can also be liberals, 'Urban Naxals', JNU – there is a whole film on JNU. So in the sense that it is creating enemies and instigating violence of thought if not action, in this case action has resulted against these supposed enemies, they are certainly propaganda in the sense that they are not encouraging any kind of reflection or thinking or you know independent investigation of your own. They are certainly propaganda because they are to be swallowed whole and then they are to be reacted to, they provoke a reaction, that is what they are meant for.

Ruchika: I also think just to add, I think there is a deliberate creation of binaries in these movies. For example Prithviraj, the movie constantly shows Prithviraj calling himself as a Hindu. That would have never happened because this term – that I am a religious person known as Hindu – would have never existed in Prithviraj's time. His entire army is wearing saffron; this connection of saffron with Hinduism is such a later innovation. In all probability they were wearing whatever colours they were wearing. And what is fascinating is Ghori's army is all in green, so it is just this very weird motley of today's ideas and today's stereotypes put on to history, and you have a depiction like this.

I have not seen the movie Chhaava, but I have heard from sources that it's very violent and there is a lot of exaggeration etc. Judging by the previous movies that I have

seen, you know you can actually make a distinction, so you have on one hand movies like Mughal-e-Azam and then you have Jodha Akbar, and then you have movies like Prithviraj, Tanhaji and then Chhaava, even Padmavat falls into that fold. There is a deliberate creation of the Muslim monarch who is certainly always putting kohl in his eyes, he has this very menacing glare. If you look at Ranveer Singh, he really typifies that with Alauddin Khilji. And they do things which are not human, for example they will show Alauddin Khilji eating raw meat – this would have been unthinkable, he is the Sultan, he would eat probably the best cooked meat out there. So this is hilarious. So this idea is deliberately being created, this othering is done.

But if you have movies like Mughal-e-Azam and Jodha Akbar, that is not how they portrayed emperors. They had their own set of historical inaccuracies, Jodha Akbar is all premised on a fictional character Jodha, we do not know if she existed or not.

Parvati: Right, and in Mughal-e-Azam we more or less know that Anarkali did not exist.

Ruchika: Did not exist right, it was a complete creation of this British writer, who called her the name 'Pomegranate Kernel', which is how the Anarkali thing comes about. So anyway, both of these movies had this idea that Mughals are a part of India, and whatever they did, they did for India, this othering is not done in both these movies, which is what I like in these movies. This other complete othering, I doubt it existed during the Mughal times. I mean it is not even the small details like oh Jodha does not exist, oh Anarkali does not exist, over here it is like oh but this idea of the Hindu just does not exist, and your entire movie is premised on it. So I think it is a very dangerous thing, because cinema has an impact, so many people including Fadnavis himself said Chhaava has caused the Nagpur violence, so you can actually imagine, but there is no responsibility that, oh if it is going to cause violence, should we be really showing things that did not exist.

Jahnavi: And not just showing, he was pushing it, he said it did a great job of portraying the truth.

Ruchika: Exactly, right, so should we be pushing an agenda, and should makers themselves just to earn a lot of blind money, etc., be doing movies like this. I think there has to be some modicum of responsibility that even makers of such movies need to take.

Parvati: I think that the contrast between narrative and propaganda – you mentioned Mughal-e-Azam, that is a great example because it is completely inaccurate, there is no Anarkali, unfortunately. And even in terms of the idea of a forbidden romance for a Mughal prince, that film has a class angle. She is a dancing girl, he is a prince, Akbar cannot abide this transgression of class, which does not actually exist at the time. Plus on top of that, there is actually a record of Salim, later Jahangir, falling in love with somebody. Akbar did not approve of that particular rishta for some reason but Salim insisted, and Akbar gave in, it is recorded in the Akbarnama. So if a prince wanted to marry someone, he would. But the film is playing to a certain kind of idea of India at the time, because the narrative at the time is about class, movement across class, but it is inclusive. It is pushing us forward towards thinking about ourselves in better ways.

And you contrast it with Prithviraj, you mentioned it just now and it reminded me of how two-three years ago, I was coming back on a long taxi ride from Noida, and we started talking, the driver and I. Initially we agreed on one point, something he had done, some traffic, almost we had an accident, and both of us agreed that he was right, the other guy was wrong. After that we had no point of agreement whatsoever on any issue, from politics to culture, and we ended up at Prithviraj. He had been saying things, I had been contradicting him; I had been saying things, he had been contradicting me. We came to Prithviraj, and he was saying things that he had picked up from the movie, and I was saying no, this is not true.

We were stuck in a traffic jam, he turned to look at me and said, ‘Madam, ek baat bolo, aap bura mat maneyga (Madam, can I say something don't feel bad).’ I said, ‘Nahi, boliye (No, say).’ He said, 'Madam, aapko kuch bhi knowledge nahi hai (Madam, you really have no knowledge).'

And I was thinking it's true for him, because he has his sources, the way I have my sources. I am reading books, or articles, or whatever, he is watching movies, he is watching YouTube videos, he is reading his WhatsApp forwards, those are legitimate sources, and as legitimate as mine. This gap is huge, and getting huger by the minute, and I really don't know how it is to be bridged. But this is the effect of propaganda, this is what propaganda does, it says there is this one truth, that's it.

A still from 'Chhava'.

Ruchika: I'd actually like to add to that, since you brought this example. Just yesterday, I had given a byte to a news channel, and they had played it as a reel on Instagram, and at least four to five people commented saying, ‘Arey aapko kuch nahi paya, aap Chhaava dekh kar aao (You don't know anything, you should watch Chhaava).’ So this idea that we'll tell a historian, who has qualifications in history, you must go learn history from a Bollywood movie, that is the level that popular history in India is playing at. I've gotten a lot of flack for this, but I think historians are also responsible, because they don't talk about history as much as they should. But this idea does certainly exist, that what Bollywood is depicting must be the truth, because it already somehow panders to our preconceived notions, and now you have it right there on the massive screen, so it must be true. That impact is something that people take on, and then you see it on the streets, in communal tensions etc., which is very important.

Jahnavi: This has been a really interesting discussion, and before we close, Parvati, today we published an article you wrote in The Wire, which was fascinating, and I would encourage all our viewers to go read it, and it talks about this time when Jahangir actually destroyed

someone's grave because he was so angry with the way that sultan had treated his father. But one of the other points you make in this article is, the people who are out to destroy Aurangzeb's grave, they do not necessarily want to say that they are morally better than Aurangzeb in certain ways. They are differentiating against him for purely religious reasons, and for they purported way he treated Hindus, but not saying that we want equality, and he did not want it, and that is the problem.

Parvati: But in a sense they do. So this is because when I was reading about what was going on with Aurangzeb, suddenly I remembered that exactly this kind of thing had happened once in Jahangir's life. Jahangir's life is full of all kinds of interesting incidents, which he records himself in the Jahangirnama, so it is a fantastic record of that time and of a person.

This happens in 1617, so it is about two years before Aurangzeb was even born, so he cannot be held responsible for any of this. Jahangir goes to Mandu. Shah Jahan has gone off to conquer the Deccan, and Jahangir is following in his wake, and he is having a great time travelling through the country, and settles in Mandu for some months. Then he goes to take a little tour, and he comes to the grave of Sultan Nasiruddin, who had died in 1510.

He is very upset, and he says that this chap, Nasiruddin, had poisoned his father. For this sin, it seems even when Sher Shah Suri came, according to Jahangir, he came and he had his retinue beat the grave with sticks. Then Jahangir comes and starts kicking it, and he gets everyone else to kick it, and then this is not enough, it is not satisfactory. So he has the grave dug up, he has the remains taken out, and first he thought, thinks he will burn them – but then, and this is one of the interesting things about history, and Mughal history, is that fire is considered divine, sacred, so then how can you pollute fire with this terrible man's remains – so then he has them thrown into the Narmada.

I think it's really weird, this incident comes out of you from the blue, why is he doing it, why is he getting so agitated? It's possible that it is because he himself has a very complicated relationship with his father. He's the apple of his eye, he's the boon that comes, but then he turns out to be the greatest disappointment of Akbar's life, he rebels against him, Akbar himself really stays on the throne for way too long, as far as Jahangir is concerned, he rebels, he goes off, there are even rumours that Akbar thought that Jahangir had tried to poison him. So maybe there must be very complicated feelings in his mind about his own father. Maybe he is trying to say, I am not this, I am better than this. So therefore this performative punishment of this man for committing patricide. It's possible, I mean, who knows what it was.

Now, if the Hindu right wants to attack Aurangzeb, stomp on his grave, I don't know what, run a bulldoze over him – there's nothing to bulldoze – what are they trying to say? I think that the fundamentalists, the Right generally across the world, and for the Hindu right certainly, it's very hard for them to think consistently, or with any particular intelligence.

So, they do say this, it is said all the time, people are saying Hindus are the most tolerant, we are the most tolerant, and then, and I found somebody saying this, a member of the VHP in one of these protests, so-called, "We are the most tolerant, but we will not let anyone who takes Aurangzeb's side live."

There's a desire to show yourself as better, but an inability actually to do so, because the whole point of it has nothing to do really with history, because of the conflation of Mughals with Muslims, which has been happening at least for decades. I mean, the 'Aurangzeb ki aulad' is now, but the 'Babar ki aulad' happens at the time of the Babri Masjid. That word, that phrase is coined then, so that's more than 30 years that this conflation has happened. So when there is a protest against Aurangzeb, a threat to attack Aurangzeb, the threat is to Indian Muslims today, because the two have been so fused.

Ruchika: Just to add, since you brought Nasir Khilji, Jahangir was also believing a rumour. Nasir Khilji never poisoned Ghiyasuddin Khilji. We have no evidence to prove that. But it's fascinating, the rancour that he has towards that grave. Considering it's a grave.

Parvati: And he has no connection with this man.

Ruchika: Exactly. I mean, it's been long time. He's just stumbled upon [the grave], and somebody's told him this, that this guy had done this. And Nasir Khilji is again, for Mandu history, he is like the Aurangzeb of Mandu history. He's not considered very nice. A lot of issues happened during his time. He's also the last ruler of the Malwa Sultanate. After him, this Rajput guy, Medini Rai, comes in. So he, poor guy, had to struggle a lot. He was also considered somebody who was a debauch, and he had a lot of women, something that we don't associate with Aurangzeb. So I think this was also a rumour that must have been very famous at that point in time.

And clearly Jahangir's rancour, like you very correctly said, comes from his own regret. In fact, the regret is also shown against the rancour that he shows towards his own son, when Khusrau rebels against him. The punishment that he gives to Khusrau is blinding him, because there is a Turko-Mongol taboo that you cannot spill royal blood. You cannot kill somebody who's royal, right? So, you will only blind him, so that it takes away his ability to become king again. You can never dream of becoming a king because only able-bodied person can.

But for the people who supported him [Khusrau], two of his best friends, the punishment is, they wrap those people in ox skin and have them paraded in the markets of Agra, to the extent that, so basically, the skin will shrivel up, right? So you will die of asphyxiation. This is what happens to them. So, the rancour that he has against Khusrau is also I think, mirroring the fact that – and Akbar was never like that with Jahangir. I think he died with this regret that his son is in bagawat against him, and he wrote letters saying, Sheikhu Baba, you should come back to me, I'm ill, meet me once before I die, and all that. I think Jahangir was on his own high trip. What's fascinating is, after he finishes off Khusrau, he goes finishing off everybody, and I'm going to come back to this whole idea.

One of the persons who was killed as a result of it is Guru Arjan Dev, because there is this idea that Guru Arjan Dev supported Khusrau, put tilak on his head as the next ruler. So, even though Akbar gave a grant to Guru Arjan Dev, now he is the enemy of the state. It's a clear political motive, it's from Guru Hargobind onwards, spinned as a religious thing. Similarly, Noor Jahan's husband is also punished like that, Ali Quli Istajlu. He's also killed in association with the fact that he was very close to Khusrau, his own son who had done bagawat against him. So, he treacherously creates this plot where he gets one of his governors to kill Ali Quli Istajlu, Noor Jahan's first husband.

So like I said, the details are very important. Vut as a country, firstly, we have an interest in history, but that void is now being filled by a lot of people who are not historians. That's primarily because historians are not filling it. So, somewhere down the line, it is our fault. And they consider this to be the only thing, this idea that I will open a book. I think Twitter had this whole thing of asking Grok, right? And we'll just ask Grok and believe whatever Grok is saying, even for history. And I'm like, although I appreciate that a lot of the RW propaganda is being busted, but at the end of the day, it's still not a book. It's still not something that historians have written about, compiled, talked about. So, I think as a nation, what can really heal us is good public history, but we don't have that.

Jahnavi: We draw this programme to a close for now. Thank you both so much for joining. Thank you all for watching.

This article went live on March thirtieth, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-four minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.