B.B. Lal and the Making of Hindutva Archaeology

If there is one name in the history of post-independent India that has had a towering influence on the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), it is Braj Basi Lal, who recently passed away last month at the age of 101.

Lal's career biography ideologically maps the trajectory ASI took after India broke its colonial shackles. Lal began his career as an archaeologist with a commitment to empirical rationality as seen from his early writing in the ASI journal Ancient India in the 1950s. However, by the 1990s, he was known as a "bhagwa [saffron] archaeologist" for his spurious claims on Ayodhya, which provided an archaeological impetus to the eventual demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992.

As a young archaeologist, Lal was trained at the famous Taxila School of Archaeology in 1944. Led by Mortimer Wheeler – the last director general of the colonial ASI – this is considered to be the first school of field archaeology. It had an enduring impact on the trajectory of post-colonial Indian archaeology, as many students who attended went to become the director generals of the ASI, including B.B. Lal who headed the ASI from 1968 to 1972.

The first time I saw B.B. Lal was during unsavoury circumstances. It was a cold winter of 1994 during the Third World Archaeological Congress (WAC 3) held in Taj Mahal Hotel, New Delhi. As a young graduate student of archaeology, I was a delegate attending the WAC 3 – a gathering of international archaeologists held once in four years. The conference opened with disarray organisation, disordered logistics, and corruption allegations.

Palpably, an unofficial gag order prohibiting any discussion on the demolition of the Babri Masjid was floating in the glittering corridors of the five-star hotel. I heard muted voices of dissent and the simmering tension in the air threatened to disrupt the conference.

On the last day of the conference, an ugly fistfight broke out on the stage of the hotel's regal ballroom. The national and international delegates sat in stunned silence. Amid a heated discussion and vociferous slogan shouting, a group of senior Indian archaeologists led by B.B. Lal and right-wing archaeologist S.P. Gupta were seen rushing onto the stage.

B.B. Lal. Photo: Twitter@ASIGoI

They snatched the microphone from the Indian delegates who had come up to the podium to read a petition for WAC-3 to pass a resolution condemning the demolition of the Babri Masjid. The conference ended wretchedly, with the WAC Council boycotting the official closing ceremony in protest.

Also read: Ayodhya: Evidence From Excavation Does Not Support Asi’s Conclusion About Temple

B.B Lal's role in transforming the ASI from a sedate government organisation excavating diverse pasts of this ancient nation to something that has been trying to prove the archaeological veracity of the ancient Hindu epic tradition is indelible.

It's because of his 'Archaeology of the Mahabharata Sites' project in 1950-52 that the earliest link between the Hindutva ideology and archaeology could be dated. Unlike the 19th century excavations of sites mentioned in Chinese travel literature by Alexander Cunningham, which had unambiguous historical origins, Lal explicitly attempted to correlate events and sites mentioned in the Mahabharata to archaeological excavations at Hastinapura and explorations of Mathura, Kurukshetra, Banawa, Panipat, Ahichchhatra, and other sites.

This led him to the controversial assertion that the pre-Buddhist Painted Grey Ware (PGW) found at these sites was associated with the Mahabharata.

PGW was identified in Ahichchhatra in 1946. During the Hastinapur excavation, it was culturally interpreted. B.B. Lal emphatically correlated PGW with Period II in Hastinapur, thereby controversially pushing the date of the events in the Mahabharata to 1000 BCE. However, in his conclusion to the excavation report of the Hastinapur excavation published in Ancient India (1954), he noted with caution that "the evidence is entirely circumstantial, and until and unless positive ethnographic and epigraphic proofs are obtained to substantiate the conclusions, they cannot but be considered provisional.”

Lal’s project was driven by the faulty logic of correlating material culture of the PGW with ethnicity – Aryan. Lal’s effort was mimetic of British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler’s equally problematic correlation between the material culture of Cemetery ‘H’ at Harappa and the notion of the invading hordes of Aryans. And now more than 70 years after his claim, there has been no evidence to suggest any relationship of PGW with the Aryans.

Again, in the 1970s, a joint project of the ASI and the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, Shimla, on the 'Archaeology of the Ramayana Sites' headed by Lal, who was motivated by the same concerns, led to excavations at Ayodhya, Sringaverapur, and Nandigrama. Importantly, Lal’s team undertook three seasons of excavations (1975–76, 1976–77, and 1979–80) in Ayodhya. But no detailed report of the site was ever published.

Only two minuscule reportages were published in the ASI’s Indian Archaeology: A Review (IAR). This excavation confirmed that Ayodhya was first occupied in the 7th century BCE.

Lal's most significant discovery was that of the earliest Jain terracotta figurine (4th century BCE) and Roman Rouletted Ware (1st-2nd century CE). This evidence showed that Ayodhya was not just part of the brisk ancient trade route, but it was a multicultural site. There was no mention of a Hindu temple at the site. The short excavation reportage in IAR ironically stated that the entire period after the 11th century “was devoid of special interest”.

However, it was in 1990 when the Ram Janmabhoomi movement was jolting the political climate in India, and more than 10 years after he had excavated Ayodhya, Lal, in an influential article in a Hindu propaganda journal, Manthan, announced that he had recovered Hindu temple pillar-bases during the excavation.

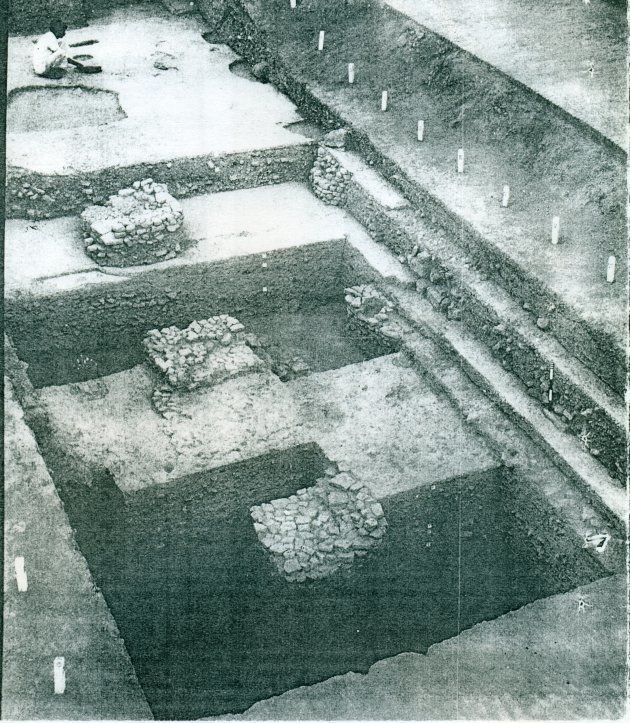

Pillar bases excavated by B.B. Lal (1970s). Photo: Courtesy Supriya Varma

Also read: Archeologist Who Observed Dig Says No Evidence of Temple Under Babri Masjid

Lal forcefully asserted his authority as an eminent ASI archaeologist behind his egregious claim that remains of a Hindu temple existed under the Babri Masjid. He allegedly provided false archaeological justification for the claim that the Hindutva fundamentalists were making about the Babri Masjid. Archaeology was irrevocably pushed into the greatest political crisis of postcolonial India.

Lal’s assertion about the presence of temple debris under the mosque had led to an acrimonious debate among archaeologists and historians in India. He led a group of historians and archaeologists, along with his collaborator S.P. Gupta, who provided archaeological justification to the political project of Hindu fundamentalism.

With this, the project of Hindutva’s appropriation of archaeology’s scientific legitimacy to pursue its divisive politics reached its logical conclusion on December 6, 1992, when the Babri Masjid was demolished.

Along with this project, Lal is also the progenitor of the other favourite Hindutva archaeological project – 'Aryanization of the Indus Civilization'. This basically means deceptively force-fitting archaeological evidence of the Harappan civilisation (3300-1800 BCE) with the Vedic civilisation (1500-600 BCE) and creating a new ethnic category called the 'Vedic-Harappans' – the authors of the 'Out of India' theory.

This project disputes the movement of the Aryans from the West, and asserts, without much evidence, that the Harappans were indigenous Vedic Aryans. This is a speculative premise devoid of any material data on the ground through which the Harappan civilisation becomes the birthplace of the indigenous Aryans who spoke the proto-Indo-European language and spread throughout the Eurasian world.

The centre of this process of 'Aryanization' – the practice of reading Aryan elements into Harappan material culture – is the river Saraswati, which, thanks to specious scholarship by Lal, moved from the mythological to the archaeological realm. I say specious because in all of his official ASI publications that dealt with the Harappan site of Kalibangan that Lal excavated, he never used the word 'Saraswati'.

He excavated the site of Kalibangan from 1960-69, but published the report only 34 years after the end of the excavation. In the meanwhile, in non-official publications, Lal routinely postulated the idea that the monsoon-fed Ghaggar-Hakra paleo-channel was actually the Vedic river Saraswati, without archaeological, geological, or hydrological evidence.

If Lord Rama was the divine centre of the property dispute at Ayodhya for Lal, then Goddess Saraswati was the celestial pivot of the making of the Vedic Harappans.

The influence of Lal was so endemic that by the late 1990s and early 2000s his students had taken firm control of the research trajectory of the ASI. Among his most prominent students are B.R Mani, who directed the ASI excavation at Ayodhya; Amarendra Nath, who excavated Rakhigarhi (1997–98 to 1999–2000); R.S. Bisht, who was the director of the short-lived Saraswati Heritage Project (2002-04) and directed the excavation at Dholavira (1989–90 to 2004–05). Today numerous students of Mani, Nath and Bisht head various departments of the ASI.

During my ethnographic work at the ASI at the site of Baror in Rajasthan in 2005, an archaeologist had said: "All senior archaeologists in the ASI have right-wing sympathies. They might not be the RSS pracharaks, but they are openly with the BJP. It is no secret that R.S. Bisht was always close to S.P. Gupta, and B.B. Lal, who, as we all know, are 'bhagwa' archaeologists. The Saraswati project has always been on the back of the minds of the RSS people. It was perhaps secondary to the Ram Janmabhoomi issue, but it was always important."

Ashish Avikunthak is a professor at the University of Rhode Island and the author of Bureaucratic Archaeology: State, Science, and Past in Postcolonial India (2021) published by the Cambridge University Press.

This article went live on October tenth, two thousand twenty two, at sixteen minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.