How a Book of Urdu Poetry Came to be Printed in Kutch in 1860

In 1860, a book of Urdu poetry was published by a printing press at Bhuj, the capital of the kingdom of Kutch. At a time when most princely states in Gujarat, Rajasthan and Maharashtra did not have a printing press, how did print reach the remotest corner of western India? And why was the book printed in Urdu, a modern Indian language with no ostensible local connections in Kutch? And why did it mostly contain verses in praise of officials of the East India Company?

§

“I don’t even know where Baboo Saheb is right now,” complained Ghalib in a letter written on June 5, 1853 to his Agra-based friend, Munshi Hargopal. “Is he up in the hills of Mount Abu or has he come to Bharatpur? There is no reason why he may have gone to Ajmer. After enduring what seems to be a never-ending wait, I now write to you. In your reply to this letter, you should let me know what you think could be the reason for the delay in his response.”

Jani Behari Lall, alias Baboo Saheb, was a man on the move in the 1850s. And the arena of his peregrinations was Rajputana, a sprawling territory fractured into 16 princely states, big and small, all under the overlordship of the Hon’ble East India Company through its Rajputana Agency, instituted in 1832. The Agent to the Governor-General, generally a military officer, was the paramount authority. He was based in Ajmer but summered in the pleasanter climes of Mount Abu.

Munshi Hargopal had introduced Jani Behari Lall to Ghalib earlier in the year in Delhi. Though Jani was already a prolific poet, he immediately adopted Ghalib as his ustad in Urdu poetry by offering a nazrana of a hundred rupees. As a further favour, he presented the royal court of Jaipur, where the ruler Sawai Ram Singh (1833–1880) had just attained adulthood, with a compilation of Ghalib’s verses. This was in the hope that Ghalib would be granted a cash award or a monthly allowance. And Ghalib was now keen to hear the outcome of Jani’s efforts.

Ghalib had had numerous disappointing encounters with the rich and powerful and was not very hopeful of success. His panegyrics had either been ignored by the royal addressees or he had been choused out of the monetary awards by unscrupulous intermediaries. Jani Behari Lall was, however, not cast in that mould.

§

Jani Behari Lall alias Baboo Saheb. Photo provided by author.

Steeped in the courtly practices of Rajputana, Jani Behari Lall hailed from a family of bureaucrats who were settled in Bharatpur for a few generations. They were Gujarati Nagar Brahmins, a community whose members traditionally occupied the highest administrative posts in the princely courts of Rajputana and Saurashtra. For example, during the long twilight of the Mughal empire in Gujarat, Raja Chhabilaram (1665-1719) and his family wielded great influence on its political affairs. In the early nineteenth century, Ranchhodjee Amarjee (1768-1841), succeeded his father and brother as the dewan of Junagadh. Both of them were scholars whose Persian correspondence was compiled to serve as epistolary exemplars. Ranchhodjee, besides other works, also wrote a Persian history of western Saurashtra titled Tarikh-i-Sorath va Halar. The domination of the Nagar Brahmin community in Gujarat, whose number would never have exceeded a hundred thousand, in the higher echelons of bureaucracy, as well as other fields such as literature and academics, continued well into the 20th century.

Members of the Jani clan (the name is a corruption of Yagnik, a category of priests) had occupied positions in the administrative hierarchy in the kingdom of Bharatpur for generations. Often, these positions were hereditary, but aspirants still needed to acquire the necessary expertise. In early 1853, when Ghalib was waiting to hear from him, Jani Behari Lall was the naib-vakeel or deputy emissary of Bharatpur to the Agent to the Governor-General in Rajputana. But he had not taken the traditional route to get there.

Born around the year 1810, Jani studied at the English school in Agra, a mere fifty miles to the east of Bharatpur. Jani was among the first generation of north Indians to receive a formal education in English. He later moved to Benares where he studied at the Sanskrit College. By the time he completed his education, Jani, like many other educated young men of that time, was well-versed in Sanskrit, Persian, Arabic and English. But he developed a special affinity for a language which had coalesced into definitive shape only in the late eighteenth century: Urdu.

The details of Jani Behari Lall’s early career are hazy and conflicting. He may have started his career as a teacher in the 1830s at the school established by Baboo Fateh Narain, a scion of the ruling house of Benares. In 1843, he was teaching at the Victoria College, Benares. When a newly appointed principal attempted to restructure the educational system in Benares and unify the Sanskrit and English sections, Jani was among the teachers who were at the receiving end of these reforms. Eventually, Jani decided to explore other career options.

In the mid-1840s, Jani Behari Lall joined the sixty-second regiment of the Bengal Native Infantry. He was the regimental schoolmaster. Jani travelled to many places in Bengal with his regiment going as far east as Dhaka. This was the period when the East India Company vigorously followed a policy of expansion through wars and conquered Punjab and a large part of Burma. The Doctrine of Lapse was also used to annex Indian royal states. Its army was always on standby, ready to march at short notice. Jani must have had the opportunity to observe these political machinations at close quarters for the eight years that he was with the Native Infantry. This stint also gave him the opportunity to develop relationships with European officials in the military and administrative cadres.

When his elder brother, Jani Bankey Lall, who was the vakeel of the state of Bharatpur at the Rajputana Agency, died in the early 1850s, Jani Behari Lall was requisitioned by the Bharatpur Maharaja to act in his stead as naib-vakeel. After the ruler, Balwant Singh, died in 1853 leaving behind an infant son, Bharatpur entered a period of uncertainty. Jani Behari Lall might have played a crucial role in ensuring a successful transition until Jaswant Singh (1851–1893) was placed on the gaddi.

From 1854, Jani Behari Lall had a new role in the same setting. Instead of being a vakeel of an Indian state, he was now munshi or secretary at the Rajputana Agency. Working closely with the Agent, he might have managed diplomatic correspondence with its sixteen ward states. This role required a command over both Persian and English, besides local languages.

In May 1857, most regiments of the Bengal Native Infantry, including the sixty-second in which Jani had served, mutinied. It was a turbulent period for the East India Company as its officers tried to ensure that the mutiny did not spread to Rajputana. Though they could not thwart it, they were, through a combination of fortuitous circumstances, able to quell it at short notice. Unlike the ruling nobility in the environs of Delhi, none of the Rajput states, especially Bharatpur, supported the mutineers and this proved to be the decisive factor. The rebellion in the kingdom of Kutch, adjoining Rajputana, was also subjugated in a similar manner.

The East India Company, as part of its policy to exert better control in the aftermath of the rebellion, decided to depute Indians who had worked in its establishment to oversee the administration of its client states. And so it was that Jani Behari Lall found himself designated the dewan or chief minister of Kutch in 1858.

§

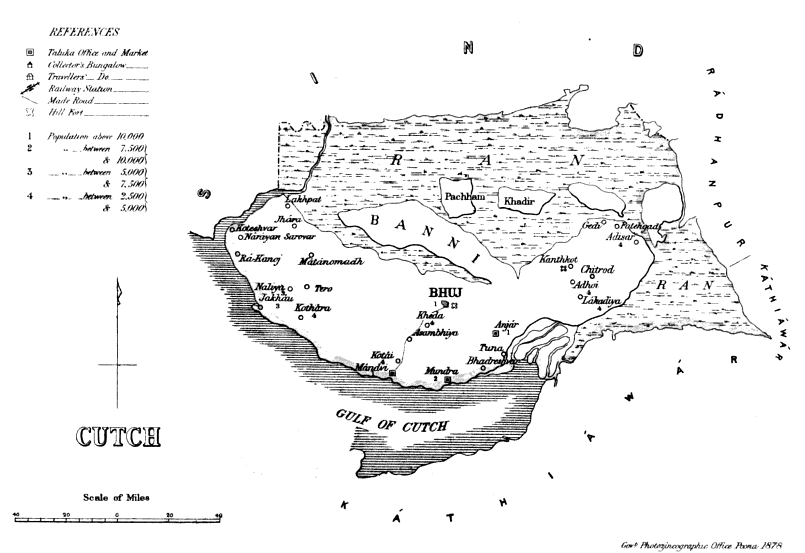

Sandwiched between the two large provinces of Sindh and Gujarat and bounded by inhospitable salt-caked deserts, Kutch might seem a place where nothing significant transpired. But that was far from the reality. Kutch had its fair share of action: border skirmishes, assassinations, fratricides, and, once, in 1741, a Kutchi prince named Lakhpat, emulating the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, usurped his father’s kingdom and imprisoned him until he died. Its long coastline facilitated a thriving maritime economy and Kutchi ships called at Indian Ocean ports from Zanzibar and Muscat in the west to Sumatra and Java in the east. Besides a brisk trade in salt and agricultural produce, Kutch was the entrepôt for African slaves and Malwa opium. Its importance in 18th century trade networks of western India can be gauged by the fact that Tipu Sultan of Mysore had established a “factory” in Bhuj to further his international trading interests.

An 1878 map of Kutch.

After Tipu Sultan’s death in 1799, this investment provided the East India Company with an excuse to establish direct contact with the kingdom of Kutch as they sought to claim his assets. They soon deputed a Political Resident to Kutch, and within two decades, in 1819, manoeuvred to depose the reigning king. His five-year-old son was installed on the throne with the titular name of Maharao Deshalji II. When Jani arrived in Bhuj in 1858, Deshalji, now in his forties and unwell, still occupied the gaddi.

Jani Behari Lall, as a dewan who had been imposed on the state, might have faced a hostile reception from the numerous power centres in the Kutchi court. But by deftly defusing a succession crisis which had been precipitated by Deshalji who wanted his younger son to succeed him rather than the crown prince, Jani seems to have established his clout. As a means of exercising effective administrative control, Jani compiled and codified all the extant local laws. And perhaps, it was to print this Kutchi law code that Jani Behari Lall requisitioned a printing press.

Having spent his youth in Agra, Jani Behari Lall would have been very familiar with the printing press and its products. The Agra Akhbar, the first Urdu newspaper from the city, began its career in 1831. Agra’s first Persian weekly newspaper, Zubdatul Akhbar, came into existence in 1833 and was long-lived. The Agra Mission Press and the Secundra Orphanage Press, both established in the late thirties, printed prolifically in many languages. By the 1850s, the cities of Lucknow, Delhi and Allahabad had also emerged as major print centres. One can imagine Jani as a diligent peruser of newspapers and a buyer of printed books in Urdu and Persian. One of his verses goes thus: “I am in love with books, say Raazi; because a book is a man’s best friend.”

§

The printing press at Bhuj was known as the Kutch Durbar Press. It was the first to be established in a princely state of Rajputana or Saurashtra. No further details are forthcoming about the press which Jani set up but it seems to have become operational in 1859. The lithographic press, could have been sourced from either Bombay or Ahmedabad and a trained printer might have accompanied it.

It was from the Kutch Durbar Press that the aforementioned Urdu book was published in Hijri 1277 (October 1860). And it was a book of poetry composed by Jani Behari Lall who wrote Urdu verse under the pen name (takhallus) of ‘Raazi’. Titled Muntakhab Qasaid va Ghazaliyat [Selected Qasidas and Ghazals], the book runs 175 pages. Lithographed on cream-coloured locally made paper, the text is neatly laid out in two columns with generous margins. The scribe who copied the lithographed text was Miyanji Abdulla bin Miyanji Ibrahim, a native of Mandvi, the largest port in Kutch. Abdulla wrote in a steady but slightly cramped style. The floral embellishments are, however, ineptly done. The print quality of the book is mediocre as might be expected in a newly set up lithographic press, perhaps operated by an inexperienced lithographer. The inking is uneven in most pages rendering the text illegible at places. The text does not contain a dibacha (foreword) or taqriz (laudatory blurbs), standard features of contemporary Urdu poetry books.

The first third of the book comprises the qasidas or laudatory poems. The recipients of praise from Jani’s pen are mostly European military officials ranging from lowly lieutenants to colonels commanding his regiment. Jani would have worked with them during his stint in the Bengal Native Infantry. He also includes an application for redress, written in the form of a long poem, addressed to the principal of Benares College in 1844. His ghazals, which account for more than half the book, were judged as competent by his contemporaries, even if he verged on prurience occasionally.

The highlight of the book is a biography of Jani Behari Lall himself, composed in Persian verse by a Kutchi poet named Munshi Amin Ahmed Sahba. Though it is composed in the highfalutin’ style characteristic of such encomiums, the qasida traces Jani’s career from his early days in Agra and Benares to his exploits in the Rajputana Agency at Ajmer and Mount Abu before he arrived in Kutch. He then mentions the high regard with which he was held by senior officials of the East India Company. At Kutch, he credits Jani with establishing the rule of law. Some of the biographical details in this article account are based on this qasida.

As a prominent Urdu poet, Jani Behari Lall features in many tazkiras (biographical dictionaries of poets), but their authors, such as Lala Sri Ram who wrote Khumkhana-e Javed, do not seem to have seen this book. Nor has Malik Ram, who profiled Jani in his account of Ghalib’s contemporaries, Talamiza-e Ghalib.

§

After the death of Maharao Deshalji in 1860, Jani Behari Lall could not long survive the change in regime at Kutch. He returned to Bharatpur in 1861 where he enjoyed a long tenure as the vakeel. In the mid-1870s, he was appointed guardian of a teenage Sajjan Singh, who had just become the ruler of Mewar. He seems to have been associated with the Bharatpur court even in the 1890s and was in receipt of a pension until his death in 1897.

Mirza Ghalib. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Whether the relationship between Mirza Ghalib and Jani Behari Lall endured after 1853 is not known, but Ghalib did get a cash award of three hundred rupees from the Jaipur court thanks to Jani’s intercession.

Jani continued his literary activities and published numerous books, most of them printed at the Matba Mufeed-e-Aam, an Agra printery which also published a few of Ghalib’s works. His works, available in a few libraries, include a grammar of the Arabic language, a handbook of the Persian and English languages, and Urdu translations of Persian classical texts such as Gulistan, Bostan and Anwar-i Suhayli. He is also known to have written an autobiography which is lost.

Not much has survived of Jani’s legacy, including his papers and correspondence. A dharamshala built in Samvat 1941 (1884/85) by Jani Behari Lall and his nephew Jani Ganapati Lall in memory of Jani Bankey Lall is all that survives in Bharatpur.

The Kutch Durbar Press established by Jani Behari Lall was the sole printing press in all of Kutch for the next ninety years. The Kutchi court clamped down on printing activities to the extent that even newspapers printed elsewhere could not be imported into the kingdom. It was only after Indian independence that private printing presses could be established in Kutch.

Murali Ranganathan is a writer and historian researching the 19th century with a special focus on print history and culture.

This article went live on September twenty-ninth, two thousand twenty three, at forty minutes past five in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.