The consecration ceremony of the Ram temple in Ayodhya earlier this year sparked a renewed communal frenzy on social media in India, with users starting full-fledged campaigns calling for reclamation of what they believe are lost Hindu temples currently under the Muslim possession.

Hordes of India’s far-right influencers are enthused by these new endeavours and are rapaciously trawling the internet for whatever they can find to substantiate their case. Of late, they seemed to have found a new preoccupation: The medieval Persian texts of Kashmir.

The political discourse in India is undergoing a rapid degeneration and quite frequently, a lot of Indian commentaries — ironically, under the rubric of “decolonisation” — are redeploying the same tropes and conventions that the colonial Indologists of yore had originally devised. The most vulnerable categories of these exploits are the medieval-era manuscripts, especially the hagiographies (tazkira) dedicated to Sufi mystics and histories (tarikh) written in Persian.

Anchored in a cultural and social milieu different from ours, these texts ought to have been understood through the conscientious interpretation of historians.

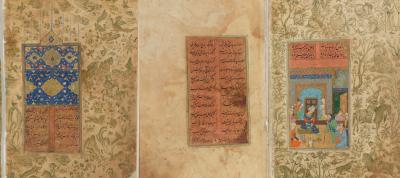

Illuminated manuscript of ‘Bustan’ by Saadi Shirazi, copied by Kashmiri calligrapher Abul Hassan Rizvi in 1505 AD. Picture: Hakim Sameer Hamdani (2024).

But wider availability of their English translations on the internet have allowed for them to be mined for particular anecdotes and stories that are removed from their original contexts and repurposed to shore up narratives they were not originally meant to serve.

Muslim structures, Hindu walls

My attention was first drawn to it a couple of years ago when a popular rightwing handle ‘True Indology’ on X (formerly Twitter) tweeted out a thread on Khanqah-e-Moula mosque in Srinagar.

It was accompanied with the claim that Khanqah, whose foundation was laid in the 14th century by an Iranian Sufi mystic Mir Sayyid Ali, was constructed on a razed Hindu temple. Although the handle posted passages from a 400-year-old Persian text, Baharistani Shahi, to corroborate the claim, he mis-identified his source as Zakhiratul Muluk – a 14th century political treatise composed by Sayyid Ali that ironically has no details about any of his undertakings in Kashmir.

The Hindu origins of Khanqah in Srinagar is not a recent development though. From Walter Lawrence’s Valley of Kashmir (1895) to Pandit Anand Koul’s felicitously written Archeological Remains in Kashmir (1935), a number of books authored around late 19th and early 20th centuries appear to have mentioned it.

Citing government records, historian Mridu Rai refers to a 1924 protest by Kashmiri Pandits demanding a right to “erect a covering” over the shrine, reaffirming their historical attachment to the Muslim shrine that was once a temple.

The controversial provenance of Sayyid Ali’s hermitage in Srinagar is elaborately explained in the four volume Tarikh-i-Hasan (1887) by Peer Hasan Shah, a celebrated 19th century Kashmiri historian

In Hasan’s telling, the demolished temple housed “120 icons of Mahadeva” and belonged to a monk named Shahpur. He narrates a story of an encounter between Sayyid Ali and the monk in which both engage in a competitive display of miraculous feats. The monk loses out and embraces Islam. The temple is destroyed, and a mosque is erected.

The dissonance between Persian texts

But this version of story is incompatible with an earlier description of the place mentioned in an endowment deed signed by Mir Sayyid Ali’s son when he presided over the construction of the hermitage in late 14th century.

Dated 1395, and preserved by the custodians of Khanqah, the covenant makes no mention of a temple, but adds that the dwelling place of Qutubuddin Shahmir, the Kashmiri ruler at that time, was dismantled to accommodate the hermitage. The document also refers to the place before the mosque as a land measuring “308 yards in length and 120 yards in breath” that was “without a fence.”

This is not to say that Hasan is concocting the account. Instead, he draws on previous Persian works – Waqiat-i-Kashmir (1765), Tohfat-ul-Ahbab (1642), Tarikh-e-Haider (1620), Baharistani Shahi (1614) – all of which have reproduced the story of the monk told originally in Tarikh-e-Sayeed Ali (1579).

Written nearly two centuries after the khanqah was built, this 16th century manuscript forms the earliest extant source for this claim. But now, new historical scholarship is putting in perspective the contents of Tarikh-e-Sayeed Ali, allowing us to fully decipher the intent and purpose of these medieval Muslim hagiographies.

A fresh effort to unknot history

Abdul Qaiyum Rafiqi, a veteran scholar of Persian studies, was first to observe that the levitating monk story featuring in Tarikh-e-Sayeed Ali was reworking of similar account mentioned in Ibn Battuta’s travelogue, The Rihla (1355), which in turn appears to have been borrowed from Fawaid-ul-Fuad, a collection of sayings of the saint Nizamuddin Awliya of Delhi, compiled probably at the turn of 13th century.

“The destruction of temples and “chastising the infidels” has been a popular theme with Persian chronicles and hagiologists in general,” Rafiqi writes in a 100 page long introduction to the second edition of his meticulous English translation of Tarikh-e-Sayeed Ali which was released recently by Gulshan Books.

Rafiqi has gone beyond translating the 16th century manuscript. He has engaged with the text very critically to the point that a number of assertions originating from it are called into question. Those include the claims that the 15th century Kashmiri Sultan Zayn-ul-Abidin was taken as a prisoner by Timur; or that Shihabuddin Shahmir, an earlier Muslim Sultan, expanded the Kashmiri kingdom to as far as Iran and imprisoned Feroz Shah Tughlaq of Delhi.

This critical approach is consistent with his previous work Sufism in Kashmir in which Rafiqi explains, among other things, how Khat-e-Irshad (Letter of Guidance), mentioned first in 17th century hagiological text Futuhati Kubrawiya, has a doubtful authenticity. A local Sufi practice (in vogue at least till mid 20th century) of holding a penitent religious procession between Khanqah-e-Moula in Srinagar and the shrine of Sheikh Noor-ud-Din in Budgam is rooted in that letter.

History repurposed to serve communal politics

By contrast, the other Persian texts that were translated into English in recent times such as Tohfat-ul-Ahbab and Baharistani Shahi have evaded similar engagement. As a result, it is common to find the content from these texts being siphoned towards social media or even big screens to serve divisive political ends. The Kashmir Files invokes Ahbab to make sweeping claims about Kashmir, Islam and its Muslim inhabitants.

There’s no denying that persecution of non-Muslims took place in Kashmir during medieval times. The Rajatarangini of Jonaraja, a more authoritative Sanskrit source, gives reliable accounts of Sikander Shahmir, the ruler and his deputy Suhabhatta as they laid waste to the temples, and presided over a campaign of forcible conversion to Islam of the “twice born.”

Ahbab recounts stories of Nurbakshi Sufi missionaries pulling down at least 56 temples in Kashmir, 22 of which the translator Kashinath Pandit is accurately able to trace in the 12th century historical text Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, implying that these accounts are not exaggerations.

Illuminated manuscript of ‘Bustan’ by Saadi Shirazi, copied by Kashmiri calligrapher Abul Hassan Rizvi in 1505 AD. Picture: Hakim Sameer Hamdani (2024).

But when mapped against the larger trajectory of the Sultanate period in Kashmir, these episodes strike more as interludes (that are deeply enmeshed with the processes of consolidating political power) than as consistent state policy.

The idea of syncretic past

The vocabulary of Jonaraja, the author of Sanskrit text, while he describes Sikander’s temple breaking spree is also interesting because he likens the Muslim king to Harsha Deva, a previous Hindu ruler of 11th century who is also known for his iconoclasm.

It’s remarkable that he isn’t distinguishing Sikander by his Muslim faith (that colonial Indologists would later do), and admonishes him and Harsha Deva in equal measure. Jonaraja also legitimises the Muslim Shahmirid rule over Kashmir by connecting the pedigree of its first Sultan to Arjuna of the Hindu war epic Mahabharata, and proclaiming that he was blessed by a Hindu deity in his dream. Of 2,150 verses that Srivara, another Hindu chronicler of Kashmir writes, 800 alone extol the Muslim ruler of that time.

Jonaraja recalls an episode when Shihabuddin Shahmir’s Hindu minister Udayashri recommended that the Sultan must melt a brass image of Buddha to mint new coins as the treasury had been emptied. But the king remonstrates him saying he does not want to be remembered as someone who “plundered the image of God.”

This shows that early Muslim rule in Kashmir was characterised by a spirit of tolerance. Thus, the claim made 200 years later in Tarikh-e-Haider, ascribing the destruction of a temple in Bijbehara to Shihabuddin, naturally becomes contestable.

These nuances, that stand in sharp relief to the communally-loaded modern day rhetoric, also pervade the long list of Persian texts composed in Kashmir during the Muslim rule.

The author of Shahi pays homage to Kashmir’s 8th century Hindu king Lalitaditya by giving him an Islamicised name, Zulqarnain. In Tarikh-e-Haider, the author compares the founding of Srinagar city at the hands of Raja Pravarasena in the 6th century with the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur laying the foundation of Baghdad.

Illuminated manuscript of ‘Bustan’ by Saadi Shirazi, copied by Kashmiri calligrapher Abul Hassan Rizvi in 1505 AD. Picture: Hakim Sameer Hamdani (2024).

As part of the research work to write Tarikh-e-Hasan, its author travelled to Rawalpindi to procure a rare volume of Kashmir’s ancient Sanskrit history Ratnakar-purana which was preserved by the descendants of Mulla Ahmad, a poet laureate at the Shahmirid court who had translated it into Persian.

As Chitralekha Zutshi observes in her book Contested Pasts, Kashmir’s Persian texts are not only dialogically connected with its Sanskrit histories, but also carry their unique imprint.

The irony of ‘decolonisation’

It was, however, the colonial historiography led by European scholars such as H.H. Wilson and Georg Bühler that accelerated the periodisation of Kashmiri history into the categories of Hindu and Muslim. It had the effect of deracinating the Sanskrit texts like Rajatarangini and Vishnudharmottara Purana from localised context, suturing them to notions of an overriding Hindu antiquity that bound Kashmir with India.

This refashioning of Rajatarangini as expression of Indic civilisational spirit, Zutshi argues, elided its place within the Persian historical tradition.

Eventually, the Persian historical tradition declined and the manuscripts were scavenged to fish out anecdotes that appeared to re-inscribe what architect and historian Hakim Sameer Hamdani calls a “paradigm of conquest and domination” which became (and wrongly so) a frame of reference against which the Muslim edifices of Kashmir, such as Khanqah-e-Moula were judged.

In this sense, Rafiqi’s rigorous exegesis of Sayeed Ali’s tarikh reverses some of the excesses of the colonial Indology that a lot of people are taking a leaf from, paradoxically, to “decolonise” India.

Shakir Mir is a Srinagar-based journalist. He tweets at @shakirmir.