The 1970s Indian Economy: A Period of Growing Strains and the Nation's Fight Against Poverty

The year 1971 was marked with several ‘big victories’ – in politics, cricket and in war – all of which had long term implications for India. The national mood was buoyant, even if the country continued to struggle with endemic problems.

Fifty years later, we look back at those times and evoke some of that mood. In a series of articles, leading writers recall and analyse key events and processes that left their mark on a young, struggling but hopeful nation.

Fifty years ago, in 1971, there were two landmark events for India. The Bangladesh war and the quick victory achieved by the Indian forces. And, Indira Gandhi’s thumping victory in the general elections due to the evocative slogan of 'Garibi Hatao’ which brought poverty alleviation to centre-stage in Indian politics.

Undoubtedly, each of the decades since Independence has brought new challenges due to the fast-changing global situation and India trying to find its feet, internally and externally. The decade of 1970s was no different since there were big global changes which impacted India, a young nation struggling with poverty and backwardness; having emerged from colonial rule just 23 years before.

1971 reflects the global and the internal challenges in a continuum with the events shaping India since the mid-1960s. These may be listed as difficulties with Pakistan, economic challenges following the drought of the mid-1960s, Vietnam war, the persistence of the Cold War, continuing balance of payment difficulties and so on.

Poverty and contradictory pulls

The terrible drought in East India in the mid-1960s setback India’s development and aggravated poverty. It led to the country’s greater dependence on the western powers for aid. There was massive import of food and also one of the biggest devaluations of the currency in 1966 from Rs 4.76 to Rs 7.5 to a dollar. India faced issues at its borders with wars in 1962 and 1965 and this led to a rapid increase in defence expenditures and massive import of arms which dented the fight against poverty. Mrs. Gandhi realising the need for food self-sufficiency went in for Green Revolution.

The droughts led to upsetting the economy’s balance and the country went for plan holidays for three years – 1966-69. There was a slowdown of economic growth compared to the pre-1965 period. So, the acceleration of growth after 1950 – such a jump has not been witnessed even later – came to an end. The Left and the Socialists were critical of the government because poverty had got entrenched. Disparities rose with big business growing rapidly while the lot of the poor hardly changed. The Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices (MRTP) Act was enacted to check the growth of the monopolies which was a result of crony capitalism indulged in by Indian Big Business.

From the late 1960s, economic regulations were tightened. The MRTP Act of 1969, nationalisation of 14 large commercial banks, the same year the Patent Act of 1970, the Industrial Licensing Policy of 1970, and the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA) of 1973 are given as famous examples.

Also read: 1971: The Year India Felt Good About Itself

The right-wing forces in the country were opposed to planning since they have been ideologically against government intervention in the economy. Though the Fourth Five-Year Plan was revived in 1969 after the three-year holiday, the planning process itself was weakened. Planning requires an overall conception of what the country wants to achieve in the economic sphere. But increasingly after the plan holidays, it was individual goals that became more important and not how they fitted in the overall vision. So, it increasingly became the sum of what individual ministries wanted rather than how the goals of each ministry would be achieved through the plan. So, for instance, employment, education and health became secondary or residual aspects.

The economic crisis of the mid-1960s also sharpened the conflict in the Congress Party. The right-wing tried to control the party but Mrs Gandhi allied with the centre-left forces and fought back and the party split. Mrs Gandhi proceeded to nationalise major private banks and abolition of the privy purses. Bank nationalisation was also necessitated by the need to spread banking into rural areas to cater to the needs of the ongoing Green Revolution. It was also required to liberate the banks from the grip of the owners who used them to fund their own companies.

The country was getting impatient with the promise of poverty removal. The peasantry was in distress after the drought in the mid-sixties and this led to peasant leaders forming their own parties. Further, continued poverty led to the armed insurrection of the Naxalite movement in 1967 in the Eastern parts of India. This was a result of the disillusionment of the youth with the development policies in the country. This was also reflected in the emergence of the angry young man in the films in the early 1970s.

All this resulted in contradictory pressures on policies from the Left and the Right. The weak consensus between these polar opposites that the Congress represented was shattered and led to confusion in policy. This was the backdrop to the events in the 1970s, especially in 1971.

Also read: How Indira Gandhi Defeated the Combined Opposition and Finished off Feudal Forces for All Time

The 1971 war

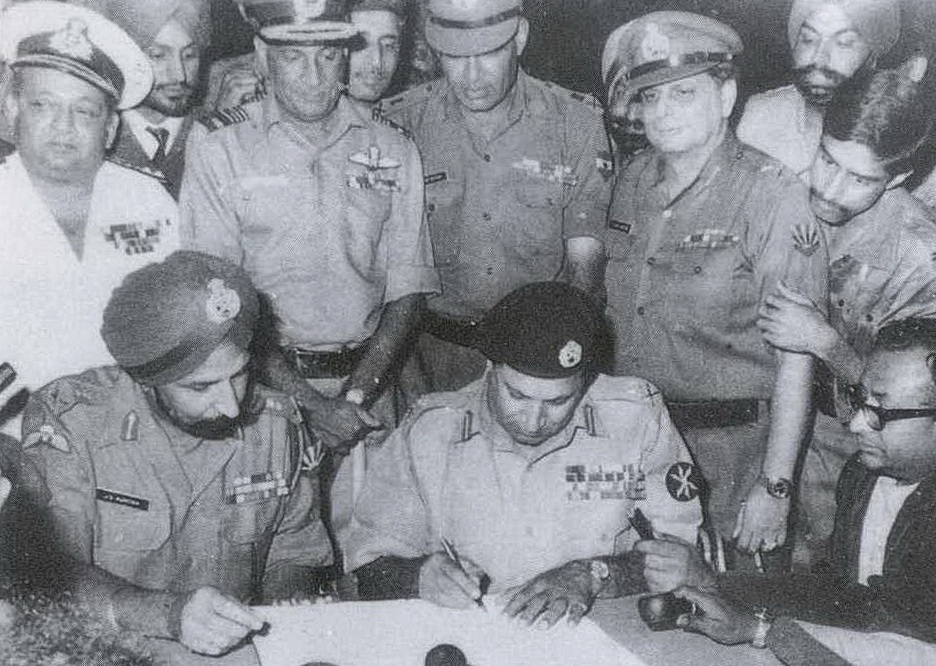

Post the 1965 war with Pakistan, there were simmering problems in the neighbourhood. These came to a head in 1971. Pakistan tried to suppress the Bengalis in the then East Pakistan and now Bangladesh. A resistance movement by the name of Mukti Bahini led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was set up with the help of India to liberate East Pakistan.

A massive flood of refugees from East Pakistan fleeing the growing oppression of the Pakistani army came to India and strained its resources. At the peak, their number was 12 million. The Indian army struck on December 3, 1971 so that the Chinese could not intervene across the Himalayas and also so that India could be seen to have been very patient before striking.

The war, the preparations for it and the burden of the refugees over a year added to the economic burden on India. Mrs Gandhi also moved for a strategic alliance with the USSR to counter the US and this marked a low in the relationship with the US. To stall India’s advancing army in East Pakistan, the US moved its seventh fleet into the Bay of Bengal. However, the speed of Indian advances and the collapse of the Pakistani forces surprised everyone and warded off any confrontation between India and the US.

In 1971, Mrs Gandhi returned to power with a thumping majority because of her firm handling of the East Pakistan situation and the clever and emotive slogan “Garibi Hatao”. However, the economic situation deteriorated in the early 1970s and Mrs Gandhi in spite of winning by a big margin faced growing political difficulties.

Lieutenant Gen Niazi signing the Instrument of Surrender under the gaze of Lieutenant General Aurora. Photo: Indian Navy website/GODL-India/Wikimedia Commons

The Indian economy in 1971

The 1971 census measured the population at 548.2 million, growing at 2.22% in the decade of the 1960s. This was the fastest growth of any of the decades since Independence and was a result of a decline in the death rate due to improvements in the health infrastructure. Of the total, 439 million or 80% were in rural areas. Of the rural population, 125.7 million were characterised as agricultural workers and of this, agricultural labourers constituted 37.8%.

The workforce in 1971 was 184 million, thus, agriculture employed 68.3% of the workforce. The share of agriculture labour rose sharply to 37.8% compared to 1961 when it was 24%, indicating that marginal farmers were losing land. This was possibly the impact of the Green Revolution, which was concentrated in a few pockets and that accentuated inequalities. Organised sector employment at 18.75 million was 10.2% of the total.

The services sector at 30.4% grew faster while the primary sector at 49.4% (including agriculture) continued to decline. This indicated the continuing structural change in the economy with the share of agriculture in output falling rapidly while its share in employment declined slowly. Indian economy continued to diversify with industrialisation proceeding apace. However, the formerly industrialised state of West Bengal continued to deindustrialise due to labour militancy and industries shifted to Maharashtra and Gujarat.

The rural-urban divide continued to grow as more and more infrastructure came up in urban areas, and agriculture and rural areas continued to languish. This was the result of the policy of trickle down followed since Independence. It was also the consequence of the dominance of the urban lobbies in policymaking.

Former PM Indira Gandhi with M.S. Swaminathan (left) inaugurating the Krishi Vigyan Mela at IARI in 1968. The two wars had dented India’s fight against poverty. Gandhi realising the need for food self-sufficiency went in for Green Revolution. Photo: MSSRF

The black economy too continued to grow. From an estimate of 4-5% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 1955-56, it grew to 7% by 1970 as per the Wanchoo Committee Report. This led to growing policy failure and also the discrediting of government intervention in the economy since public services suffered. Crony capitalism flourished in this period enabling strong monopolies and oligopolies to flourish in the economy with political protection. This was concluded by the Hazari Committee Report in 1969.

To industrialise more quickly, resources were needed and the highest marginal tax rate reached 97.5% in 1971 when Mrs Gandhi was the finance minister. The attempt was not only to collect resources but also cut luxury consumption. White goods remained in short supply and there was a waiting period to buy them which led to their black marketing; there was a premium on getting a two-wheeler or a telephone. In spite of the high tax rates, resources remained short.

National income grew at 1.4% but the per capita income declined by 0.9% in 1971-72 in continuation of the trend of a slowdown since 1966. Agriculture production responded to the Green Revolution with productivity rising while the area under cultivation remained unchanged. Food and non-food production declined slightly compared to the previous year but was much more than in 1965-66. Thus, the net availability of cereals and pulses at 467.3 grams per day remained satisfactory. Index of industrial production increased from 104.3 to 110.2 in 1971-72.

Inflation moderated in 1971 with the wholesale price index rising 5.6%. In fact, even this was driven by the manufactured products index which rose by 10% while the primary articles index rose by 1%. Consequently, terms of trade moved against agriculture. But the lull in price rise was temporary since prices galloped in the next two years.

Also read: The Year When Indian Cricket Came of Age

Globally, the US went off the gold standard and there was a dislocation of the Bretton Woods system in 1971. Rupee got pegged to the dollar. Foreign exchange reserves were at Rs 480.4 crore and remained at a comfortable level due to the continuing aid of about Rs 1,000 crore. This helped cover the current account deficit.

India returned to the path of planning with the Fourth Plan which targeted growth and self-reliance. These were the lessons of the drought of 1966-67. Globally, the Vietnam war continued to escalate with the heightened Cold War. In the US, youth protests against the war escalated putting pressure on the US government so that it could not fully pressurise India.

To conclude, 1971 was eventful due to the war to liberate Bangladesh and Mrs Gandhi’s big victory using the 'garibi hatao' slogan. She became an undisputed leader of the Congress party and also the country. But the strain on the economy grew even though it recovered from the lows of the severe drought of the mid-1960s.

Arun Kumar is Malcolm Adiseshiah Chair Professor, Institute of Social Sciences and author of Indian Economy since Independence: Persisting Colonial Disruption and Indian Economy’s Greatest Crisis: Impact of the Coronavirus and the Road Ahead.

This article went live on March tenth, two thousand twenty one, at fifty-five minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.