Infrastructure Isn’t Enough: Lessons For Swachh Bharat From W.G. King and the Madras Model

It has been 90 years since William G. King passed away on April 4, 1935, yet his visionary efforts in public health remain remarkably relevant today.

King (1851-1935) was the sanitary commissioner of Madras from 1892 to 1905, a professor of hygiene at the Madras Medical College and later inspector-general of civil hospitals in Burma. He is best known for pioneering preventive public health initiatives and advocating systematic sanitation as foundational to community well-being.

The allocation of resources between preventive sanitation and curative medicine is an enduring dilemma in public health policy, vividly exemplified by King's tenure as Madras's sanitary commissioner.

King's advocacy for sanitation-driven initiatives and his persistent critique of colonial authorities' policy to prioritise curative medicine over preventive infrastructure including systematic sanitation, sanitary engineering and public health education echo contemporary debates, especially in the context of programs like India's Swachh Bharat Abhiyan.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Madras Presidency was grappling with severe public health crises, including cholera, plague, smallpox and malaria. Epidemics frequently ravaged populations, exposing profound deficiencies in the colonial public health infrastructure.

In response, by 1890, the majority of local governments in colonial Madras had sanitary boards, a sanitary engineer and allocated funds for sanitation projects.

It was the public conscience of many sanitarians in the colonial bureaucracy, focused on bringing advances in preventive medicine and sanitary engineering to the worse-affected populations, that laid the early foundation of Madras's public health infrastructure. Their efforts in creating an autonomous body of “certified sanitary inspectors”, working in close cooperation with the medical establishment and local governments in the presidency, more than a century ago, have never been more relevant.

King was notably critical of the Indian Medical Service and the Indian Civil Service for neglecting rural sanitation. He believed empowering local communities through sanitary education would create a strong and respected foundation for public health.

In 1895, largely due to King's insistence, the Madras Medical College launched a compulsory sanitary inspector's course – unique even compared to contemporary British standards. By 1908, the duration of this course was extended to five months, admitting only matriculates and making bacteriological demonstrations compulsory. By 1909, Madras employed 683 sanitary inspectors, a number cited by the British government of India as exemplary.

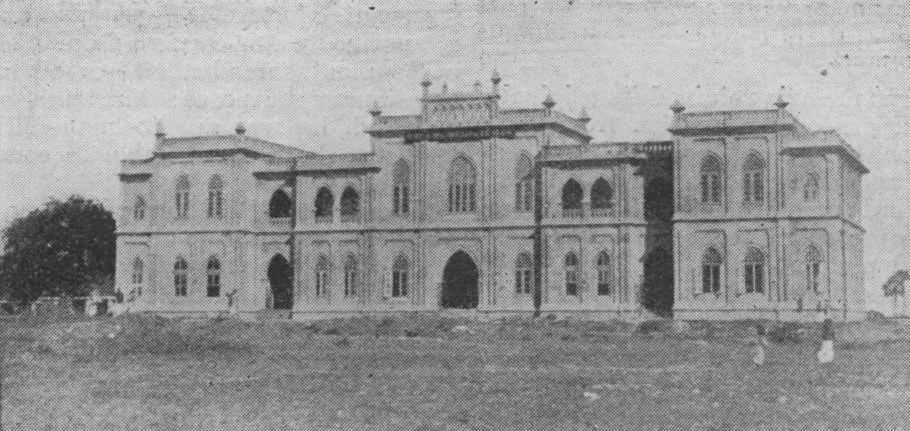

The establishment of the King Institute, named in his honour, became central to further public health developments. In this photo the institute is seen in 1914. Photo: Unknown author/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain.

King understood that sanitation was not just a technical issue but one deeply intertwined with people’s daily lives. He wanted sanitation inspectors to have intimate knowledge of local customs and conditions. He welcomed the opportunity for training in new advances in sanitary engineering and fought hard to develop a course that was not only well attuned to the tropical climatic conditions of Madras, but also modern in its technical application.

His aim was to institute a “diploma in sanitary science as applied to the tropics” for sanitary inspectors in Madras that could ultimately build the public health infrastructure of the presidency in the long term, rather than serve the immediate, mainly commercial goals, of the colonial authorities at the time.

King is known to have pioneered rural relief measures like “itinerating dispensaries”, where medicines were distributed directly in villages along with instruction pamphlets written in the vernacular in Madras. This approach aimed not only at immediate relief but also fostered greater cultural sensitivity among British medical officers, who, King argued, would learn more about local conditions through direct engagement.

Despite facing substantial resistance from his medical peers, who often viewed sanitation expenditure as superfluous, King persisted. He firmly believed in creating a cadre of trained, knowledgeable and empathetic sanitary inspectors who could effectively bridge the gap between colonial authorities and local communities. These inspectors were tasked strictly with sanitary duties and intentionally separated from curative medical roles to maintain clarity and efficiency in their mandate.

However, King's steadfast commitment eventually put him at odds with powerful colonial interests, particularly regarding malaria control. His insistence on addressing malaria through environmental measures – like improved drainage and the elimination of mosquito breeding sites around irrigation projects – clashed directly with colonial economic priorities that favoured pharmaceutical solutions such as quinine distribution.

King's insistence led to his exclusion from leadership at what is today the King Institute of Preventive Medicine, highlighting the colonial administration’s preference for economically convenient solutions.

King's foresight and advocacy gained posthumous validation. Decades after his tenure, his ideas profoundly influenced Madras's public health framework.

The establishment of the King Institute, named in his honour, became central to further public health developments.

His emphasis on systematic training and localised sanitary solutions such as tackling water-borne diseases and setting up sustainable drainage works laid the groundwork for subsequent expansions in preventive medicine across the region. By the early 1920s, following the Government of India Act of 1919, Madras introduced a complete district health service incorporating King’s ideas extensively.

Parallels between criticisms of Swachh Bharat and King's criticisms of colonial policies

Today, India's Swachh Bharat Abhiyan resonates with King's legacy, being a nationwide campaign initiated to promote sanitation and eliminate open defecation. Launched in 2014, the policy represents a significant recognition of sanitation's critical role in public health.

However, despite notable successes in increasing access to toilets and enhancing cleanliness awareness, the program continues to encounter criticisms reminiscent of those raised by King more than a century earlier.

Critics of the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan highlight several parallels to King's struggles, particularly regarding the emphasis on infrastructure without sufficient investment in developing a scheme for the education, training and certification of sanitary inspectors who are familiar with local language, culture and public works infrastructure.

Building toilets, while vital, does not automatically translate into their usage or improved hygiene practices unless accompanied by specialised training in sanitation and socio-cultural engagement at the neighbourhood level.

Drawing from King’s critique of colonialism’s preference for quick fixes over prevention, critics warn that sanitation systems – unless supported by ongoing public health education, active collaboration with public works departments, and grassroots engagement – may deteriorate or be abandoned.

Furthermore, King's insistence on tailoring sanitation strategies to local customs and environmental conditions provides a crucial lesson for modern initiatives. For instance, Swachh Bharat's uniform national targets and construction standards sometimes overlook regional ecological and socio-cultural diversities, underscoring King's point that effective sanitation requires highly localised, culturally sensitive interventions.

Still, the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan's efforts to prioritise sanitation within national health policy must be recognised positively. Its ambition to mainstream sanitation aligns closely with King's long-held belief that preventive measures could significantly enhance public health outcomes and economic productivity. This alignment underscores a progressive shift from mere symptomatic treatment toward addressing underlying public health determinants, a principle King passionately advocated.

King’s work invites contemporary policymakers to reflect critically on the enduring importance of balancing curative and preventive public health measures. His experiences in colonial Madras highlight the necessity of robust public health pedagogies and education, localised strategies in collaboration with related departments like the PWD and drawing from community health and development, and adequate financial commitment to preventive health infrastructure.

As we mark 90 years since King's death, revisiting his advocacy provides valuable insights into constructing resilient and effective public health systems capable of confronting present and future challenges.

Aarti Kawlra is a social anthropologist affiliated to the French Institute of Pondicherry, and academic director of the education collaboration programme, Humanities Across Borders at the International Institute for Asian Studies, Leiden.

Vignesh Karthik K.R. is a postdoctoral research fellow of Indian and Indonesian politics at KITLV-Leiden; and author of the forthcoming book The Dravidian Pathway: The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and the Politics of Transition in South India (C. Hurst & Co/ Westland Books/Oxford University Press 2025).

This article went live on June sixteenth, two thousand twenty five, at thirty-eight minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.