What We Know About the Last Few Days of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose's Life

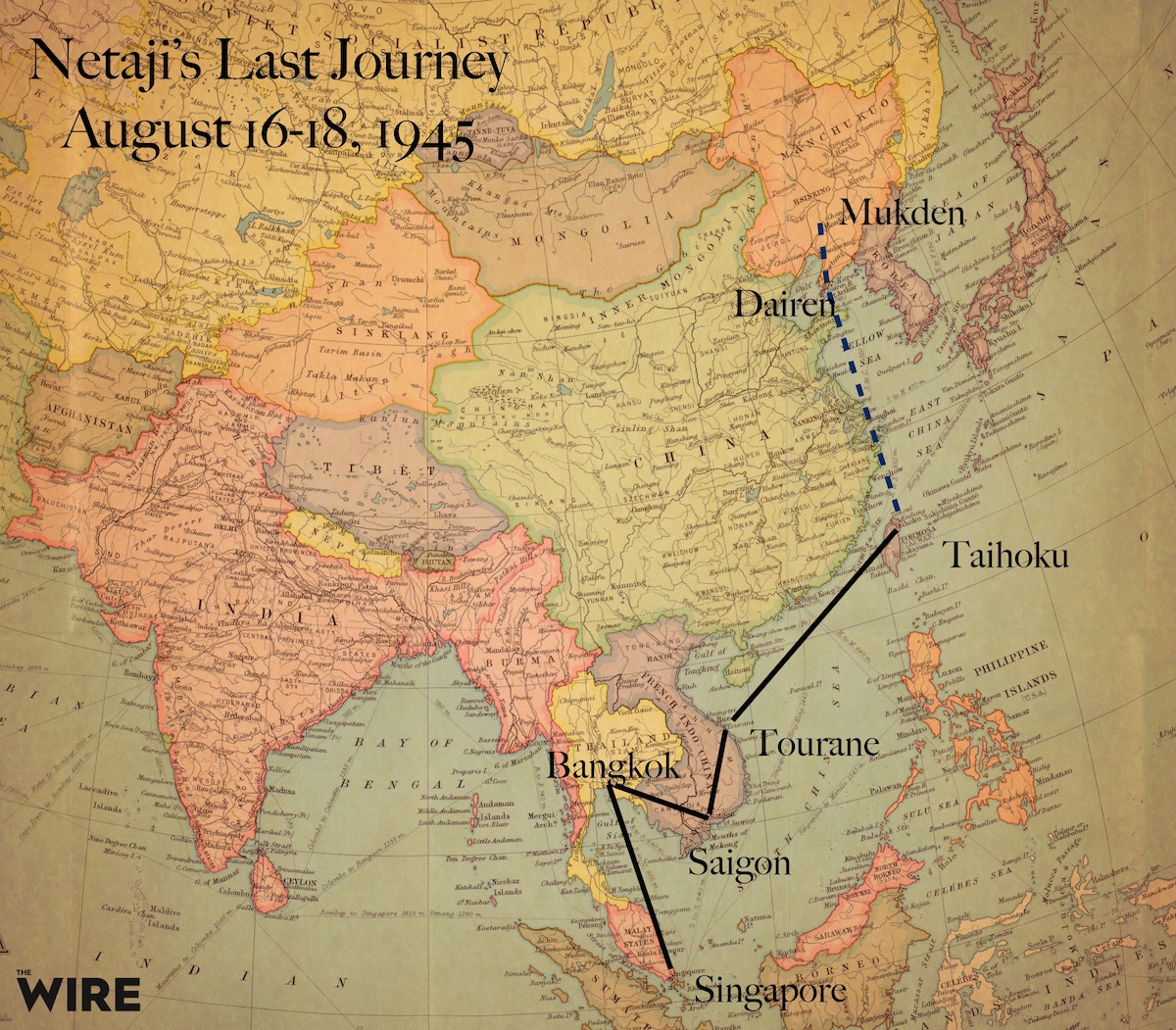

Today marks the 75th anniversary of the death of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, who perished in a plane crash in Japanese-occupied Taiwan on August 18, 1945.

By the second week of August 1945, World War Two had all but ended in Asia. Japan was on the ropes anyway but the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ensured its quick surrender. Japan's allies in Asia knew they had to prepare themselves for what was to come. Dr Ba Maw, ex-prime minister and head of the Burmese State, was making arrangements for his journey to Tokyo. José Paciano Laurel, president of the Republic of Philippines, was already in Japan, and other leaders of the Axis states in East Asia were preparing to formalise their surrender.

Japan had just a few days before its soldiers laid down their arms. The war was over. But Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, prime minister of the Provisional Government of Free India (PGFI) and chief of the Indian National Army (INA), had other plans. His mission to free India of British rule remained to be accomplished.

Bose returned to Singapore from Seremban on the evening of August 13. Japan’s surrender was not India’s surrender. Many ideas must have crowded Netaji’s mind. He conferred immediately with his military and civil chiefs. The cabinet discussion went on throughout August 14. Bose hinted that he was inclined to stay and face surrender with the rest. His cabinet wanted him to go – somewhere, anywhere. Bose kept thinking about the many alternatives.

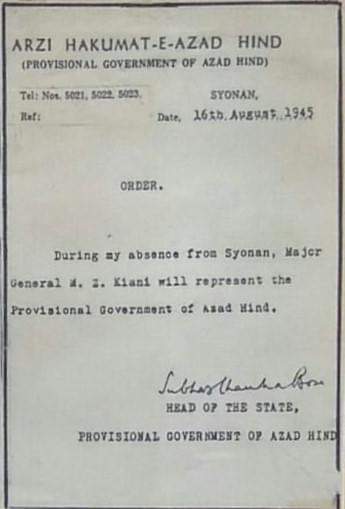

General M.Z. Kiani was given the charge of INA in Singapur and Malaya.

The Japanese armed forces virtually collapsed after August 15. There was little advice to be obtained from them in Singapore. Bose decided to leave. General M.Z. Kiani was given the charge of INA in Singapore and Malaya. Debnath Das was sent a secret telegram on August 16 morning to Bangkok, stating that he should take care of the INA treasures and keep them secretly.

Netaji arrived at Bangkok, then the seat of the PGFI, before noon on August 16, 1945. He went to the headquarters of the Indian Independence League (IIL) and met members of the Azad Hind Government and informed them that Japan has surrendered.

Netaji handed over charge to General J.K. Bhonsle of the INA in Bangkok. The cash in hand at Bangkok was disbursed to pay two-three months advance salary to the INA warriors, and to hospitals and other Indo-Thai charitable associations.

The INA treasure were in 17 sealed boxes with descriptions of the contents. The boxes were kept in Netaji’s bedroom. The place was guarded by the INA military police.

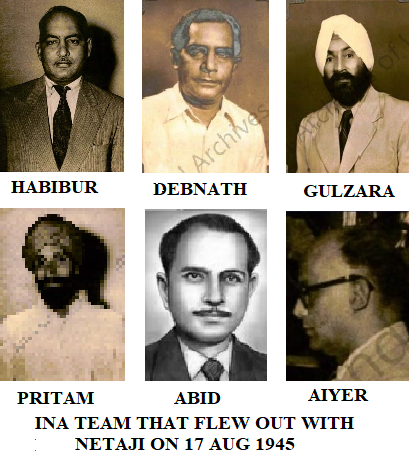

On the midnight of August 16-17, 1945, Bose collected all officers at his residence and discussed with them various plans. He chose S.A. Aiyer, Debnath Das, Colonel Habibur Rahman, Captain Gulzara Singh, Colonel Pritam Singh and Major Abid Hasan to fly out with him to a safe place. None of them were informed where they were flying to. But they presumed that they were heading for Dairen, where Netaji would explore Soviet asylum for the future struggle.

Later that night, Netaji sat with his personal valet Kundan Singh to check the contents of the steel treasure boxes. He got the boxes repackaged for taking along with him on the journey.

Also read: The Treason Trial of Netaji That Never Happened

The last journey

At about 6 am, the officers assembled at Bangkok airport. The Japanese were discussing that it would be difficult to conceal such a big party. Netaji told General Isoda that it was essential that he be accompanied by a number of officers as his primary objective was to continue the struggle for India’s freedom and not just to hide himself.

The team took off for Saigon in two planes accompanied by some Japanese officers. Netaji left with two small and two large suitcases containing the valuables. The team reached Saigon at around 8-9 am. What was unexpected was that the Japanese in Saigon could not provide a separate plane for the INA men. The Allied powers had instructed them not to fly any plane without their permission. However, there was one plane waiting at the aerodrome to fly to Tokyo, with 11 already on board. They could carve out one space from there for Netaji. Netaji strongly refused to accept this offer. He wished to take the entire team with him. The INA officers, for the sake of Bose's safety, agreed to let him go but with one person for company. Netaji chose Habibur, to which the Japanese agreed.

The team took off for Saigon in two planes accompanied by some Japanese officers. Netaji left with two small and two large suitcases containing the valuables. The team reached Saigon at around 8-9 am. What was unexpected was that the Japanese in Saigon could not provide a separate plane for the INA men. The Allied powers had instructed them not to fly any plane without their permission. However, there was one plane waiting at the aerodrome to fly to Tokyo, with 11 already on board. They could carve out one space from there for Netaji. Netaji strongly refused to accept this offer. He wished to take the entire team with him. The INA officers, for the sake of Bose's safety, agreed to let him go but with one person for company. Netaji chose Habibur, to which the Japanese agreed.

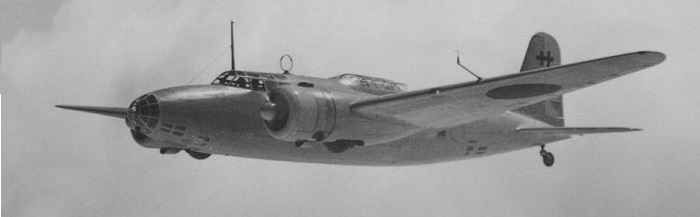

The plane was a two-engine bomber with the capacity of carrying one tonne load. Eleven Japanese were already there, waiting for Netaji. When Netaji arrived General Isoda asked him to board the plane. Netaji replied, “I am not going, I am waiting for the second car.” The treasure was in the second car.

When the car arrived, the boxes were found to be fairly heavy. The pilot was reluctant to take the additional weight, but Debnath Das and Pritam Singh catapulted the boxes inside. Netaji’s request for accommodating another person in addition to Habibur was met with a choice – either the boxes go or the third person. Netaji chose the former. The engine of the plane had already started roaring. The bomber took off from Saigon at 5:20 pm, August 17.

The bomber plane Ki-21.

While the passengers were having a night’s halt at Tourane, the pilot detached the machine guns, its ammunition and anti-aircraft gun that were fixed to the plane, to reduce weight.

The plane took off from Tourane at sunrise, August 18. It reached Taihoku (Taipei) at noon. It was filled with gasoline to capacity. The team was headed for Dairen (Dalian) in Manchuria to drop off Shidei. Netaji agreed to go with him and to Mukden (Shenyang), the capital of Manchuria. It took off at around 2-2:30 pm.

The seating arrangement inside the plane remained the same. Four crew including two pilots in front, General Shidei behind them on the right. Netaji besides the petrol tank, on the left of Shidei, Habibur behind Netaji. Lieutenant Colonel Sakai behind Shidei. Major Kono, Lieutenant Colonel Nonagaki, Captain Arai and two others in the rear. Netaji’s baggage was near his feet.

No sooner was the plane was airborne, at about an altitude of 20-30 metres, there was a sound of an explosion followed by three-four loud bangs. The plane nosedived. The propeller on the left side of the plane fell off. On crashing beyond the concrete runaway, the plane broke into two.

Also read: Netaji, Now Appropriated by the Rightwing, Was Unflinching in His Commitment to Religious Harmony

The crash affected different persons differently. Seven people ultimately survived, with various degrees of injuries. Netaji was covered in petrol, and he had to rush out of the debris through the fire. Habibur followed him. Netaji’s clothes and his body caught fire. Once outside, Habibur took off Netaji’s sweater and clothes with great difficulty and laid him down on the ground. Major Takahashi, one of the survivors, made Netaji roll on the ground to put out the fire. Netaji’s body and face was scorched with heat and his hairs singed. Habibur’s hands and right side of face were burnt but his clothes did not catch fire. He too lay by Netaji’s side.

Shortly afterwards, Netaji along with the other injured persons were taken to a small military hospital – more like a first-aid treatment centre – nearby. Netaji’s condition was the most serious. He was burnt all over, and his skin had taken on a greyish colour, like ash. His heart too had burns. His face and eyes were swollen. His burns were of the severest type, third degree. He had a high fever but surprisingly, he was in his senses.

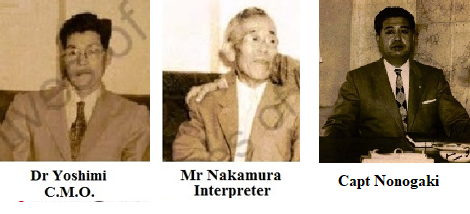

The chief medical officer, Dr Yoshimi, opined that Netaji was not likely to survive till the next morning. Ointment was applied all over his body; his burns were dressed and he was bandaged all over. He was given three intravenous injections, and six other injections for his heart. Some blood from his body was let out and a blood transfusion given. Netaji was conscious at the beginning, so an interpreter, Juichi Nakamura, was called to assist Netaji speak to the Japanese personnel if desired.

Also read: Laying to Rest the Controversy Over Subhas Chandra Bose's Death

At 7-7:30 pm, Netaji’s condition deteriorated. In spite of administering stimulants, his heart rate and pulse did not improve. Slowly, his life ebbed away. He breathed his last shortly after 8 pm. Dr Yoshimi made out a medical certificate on his death, writing his name as ‘Chandra Bose’ in Japanese. Dr Yoshimi, Dr Tsuruta, two nurses, Nakamura, Habibur Rehman and one military policeman were by Netaji’s bed side at the time of his death. Immediately after Netaji passed away, the Japanese stood up and paid respect to his body, saluting. Habibur knelt by Netaji’s bed and prayed.

Besides Netaji, the crash resulted in the death of Lieutenant Colonel Shidei and all four crew members, all sitting in the front.

The remaining five

Gulzara Singh, Pritam Singh, Abid Hasan and Debnath Das flew out of Saigon to Hanoi on August 20. Ayer was taken to Tokyo on the same day. All five received the news about Bose's death on August 20. General Bhonsle, in Bangkok, was updated about the accident and subsequent death on the night of August 18, when he received three telegrams in succession from 11 pm onwards.

Cremation

Netaji was cremated on August 20 at Taihoku. With communications in shambles and amidst utter confusion in the ranks and files of the Japanese, the local authorities avoided taking the responsibility of recording or declaring the death of a leader of a foreign friendly nation. It is believed that they changed the name on the death certificate to Ichiro Okura. The ashes were collected in a wooden urn and kept at the Nishi Honganji Temple at Taihoku.

Official announcement

The official Japanese radio announcement on Netaji’s death was made on August 23. The news spread all over the globe. Indians were dumbstruck by the tragic news. To many, the death was unbelievable. They took it as yet another deception planned by Netaji to escape from the clutches of the Allies.

The Allied Forces too did not believe the news at first. (You can read more about their investigations here.)

The route the flight took.

The IIL investigation

The IIL carried out an investigation in late 1940s-early 1950s and brought out a report in 1953 stating that while it agrees with reports that Bose passed away on August 18, 1945, the aircraft crash had not been an accident but an act of sabotage.

They said the Japanese officials could neither risk shielding Bose from the Allies lest he resurfaced, nor hand him over to them and endanger relations with Indians. So, to save themselves from the wrath of both India and the occupation forces, Japanese officials diverted the route of Bose's plane, separated him from five of his six associates and manipulated the crash. The plane crash was deliberate.

Also read: The Dishonesty of Those Who Exploit and Abuse the Name of Netaji

The treasures

The Japanese army engaged some people to pick up valuables scattered next to the crash site. They were told that the charred jewellery belonged to Bose. The search continued till it became dark. After collecting the articles, they were put in an 18-litre gasoline tin can and sealed. At the army headquarters, Lieutenant Colonel Shibuya transferred the contents to a wooden box and sealed it once again. The wooden treasure box, 3’ x 2½’ x 2’, was sent to Tokyo on September 5 with Habibur, under the custody of Sub Lieutenant Hayashida, together with Bose’s remains.

Ba Maw halted overnight at Taihoku on August 23, 1945, on his way to Tokyo. His plane carried the box containing the remains of Lieutenant General Shidei on August 24.

Rickety plane

From a series of article published in the Japanese edition of Yomiuri Shimbun from Tokyo from August 27 August to September 4, 1969, we find an interview with Lieutenant Colonel Shiro Nonogaki, himself a pilot and a survivor of the crash, where he recorded that the plane “failed previously on landing in Singapore when the propeller was bent. The plane was damaged when it crash-landed there. The propeller was not replaced but it was just provisionally mended by hammer. It is presumed therefore that a blade of the propeller previously damaged and mended provisionally was torn off as the pilot stepped up the pitch of the propeller rotation. During the time of War many such planes were in commission but then we had not the least idea that the plane was such a rickety piece.” Nonogaki continued, had he known that the plane was so dangerous, he would have suggested the reduction of more load.

There is no information in the public domain of any investigation on the reasons for the crash. It's possible that the three Netaji files still held as 'classified' in Japan hold the key.

Sumeru Roy Chaudhury is an architect graduated from IIT, Kharagpur. He was the chief architect of the CPWD. He has studied the Netaji files and related documents in detail.

This article went live on August eighteenth, two thousand twenty, at eight minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.