The Unsettling ‘Resettlement Card’, or My Family's Memories of Partition

“So, where are you from, originally?” asked the man I had recently matched with on a dating app. My current location was Delhi. “I’ve been in Delhi since I was 12-days-old, but I was born in Rohtak,” I said. “But, I belong to neither place: Delhi was a consequence of economic migration for my parents and Rohtak was just an accidental home”. Surprised, he probed for details and I relayed in as few words as possible the itinerant lives of my 1947-Partition refugee grandparents and their subsequent generations. At the end of my little monologue, he said he’d like to hear more of it when we meet; probably the only polite response to a potential dating partner with inexplicable nostalgia.

My mother grew up in my birthtown, but her parents’ home was in a village now untraceable on Google Maps (it’s probably renamed): ‘Bagh Kukarey’ in Jhang Maghiana (as it was then called), Panjab, of present-day Pakistan. As for my paternal side – dadi maa (grandmother) and dad (grandfather) left Lahore and migrated to Simla (where my father was born) and then moved around on postings for dad’s civil servant’s job across the Indian (or East) Punjab state as it got further divided into Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana.

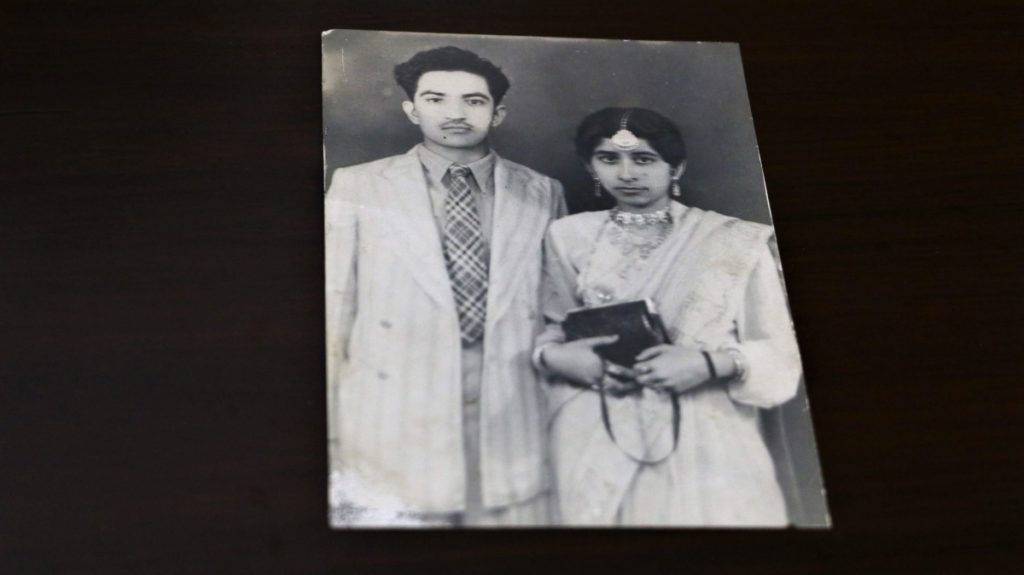

A picture of the paternal grandparents as newly weds, taken in Lahore, post-1945. Credit: Author provided

Until 2017, I grew up hearing that dadi maa and dad had relocated to Simla – that teemed with British India’s offices and government servants, one of whom was dad – before the borders were redrawn. It led to the belief that this set of grandparents, unlike the maternal ones – nani maa (grandmother) and pitaji (grandfather) – had escaped the worst of communal violence. The former had mostly happy stories to recount and since they outlived nani maa and nanaji – with dadi maa being around till 2017 – Lahore became a more relatable home in my mind. I would have been a Lahori, if it hadn’t been for the Partition, I tell almost everyone.

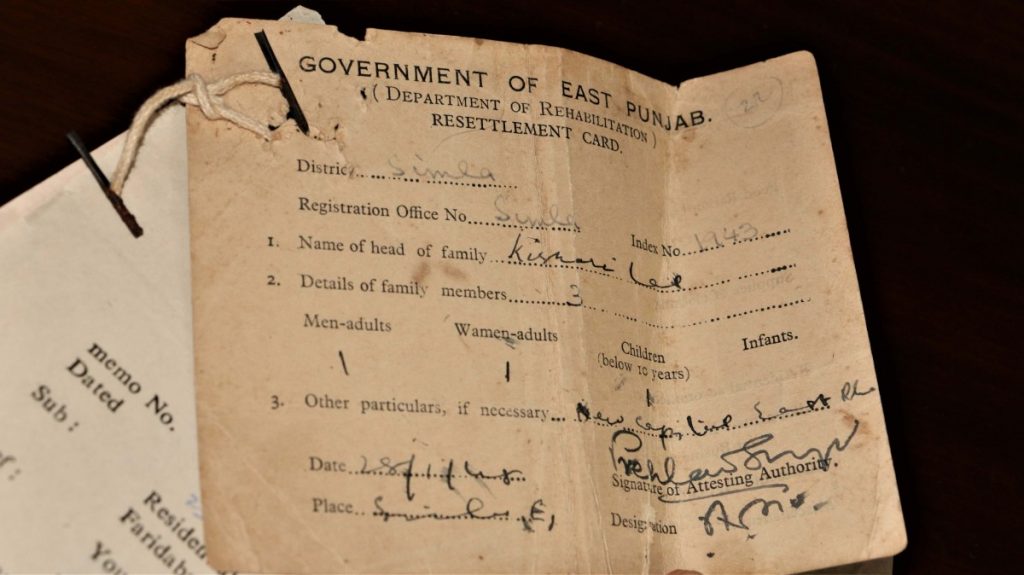

A few months after my grandmother – the last of my direct grandparents – passed away in 2017, I made a trip to her house in Rohtak, searching cupboards for nothing in particular but with the longing to find a keepsake. Little spiders broke into sprints as I removed layer after layer of books and diaries. Without ceremony, I ended up holding a set of brittle, yellowing and dusty papers, among which was one that decided the fate of my family: a resettlement card. It was unassuming at the size of a passport, yet my hands quivered. Titled ‘Government of East Punjab (Department of Rehabilitation)’ the card recorded one person each under “men-adults, women-adults, and children (below 10 years)”. With dad’s name under “name of head of family”, the other two digits were dadi maa and my uncle, born May 31, 1947. It recorded the registration office as Simla and was, strangely, dated January 28, 1948.

Resettlement Card. Credit: Author provided.

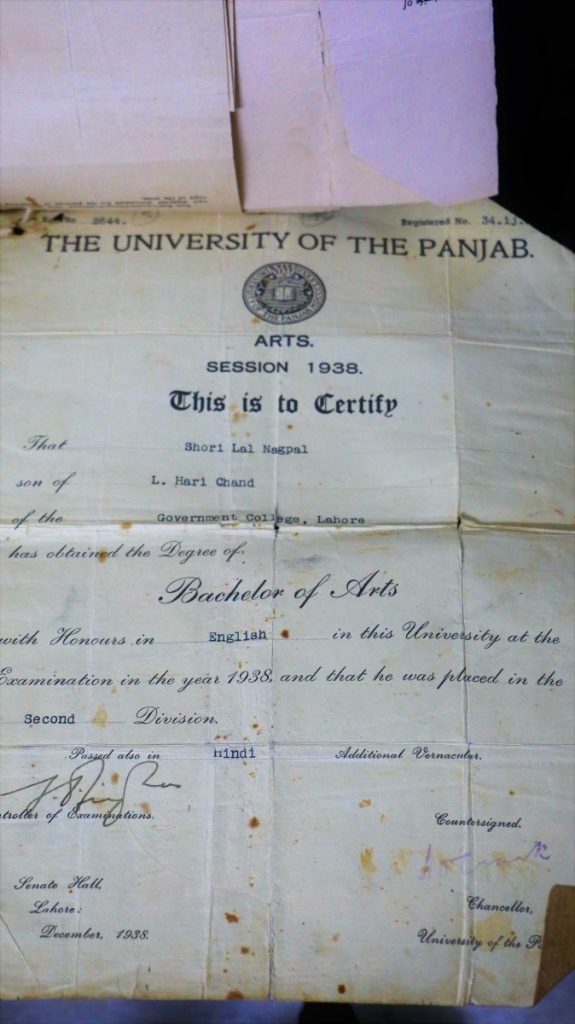

But, they were supposed to have migrated ahead of the Partition. Was it a story they had made up to bury the details of their relocation and all that they saw and experienced? Was their story beyond speaking and recollection? The only nugget I did know from this side of the family: chote dad’s (grandfather’s younger brother) BA final exams were interrupted due to Partition. He used to live with his brother and his wife (my dad and dadi maa) then. Several months later, his university had sent letters to offer degrees conditionally. Willing students would have to serve at refugee camps they were directed to and would receive degrees upon completion of the specified duration. He managed to complete the task and his degree as well.

On the other hand, nani maa and pitaji had fled through a combination of walking and bullock cart rides, carrying just one rupee, while all their valuables stayed buried inside the courtyard of their house that had a khirnee tree with delicious fruits. The old pitaji’s mother perished due to illness on the way. Lighting a funeral pyre for her as per their Hindu custom meant attracting the wrong kind of attention. So, they buried her in the forests they were passing. Pitaji always shuddered while narrating these ordeals.

But, there was never a story about how dadi maa and dad had travelled. There were plenty about their Lahore, though; all cheery details. I know well about the trinkets at Anarkali Bazaar; and can recite in my sleep the Persian couplet written on Noor Jahan’s mausoleum. Lahore was the city chote dad, from where he had caught a bus to Amritsar, to escape a beating from his brother for performing poorly in matriculation exams. It was the place of placeable belongings like Government College, Lahore, where dad completed his BA (Honours) in English, in 1938 (This BA degree was also found in the bundle of documents). Dadi would describe even the coordinates of her childhood home in Lahore, but would say she didn’t remember much about the time of Partition. They had relocated “much before”, would be her response. The inherited memories were like my own. But perhaps, trauma had ways of masking itself; forgetting could be an everyday striving of the afflicted.

Grandfather's BA degree from Government College, Lahore. Credit: Author provided

It was likely that the resettlement card was issued at a later date. Or, that they had, indeed, circumvented the worst of Partition. But, it is beyond belief that they had no difficult memories of what transpired around that time. A document, that would normally be considered reliable proof or admissible fact, had punctured my inherited memory and unsettled this immigrant family’s micro-history. It is, nevertheless, an invaluable document to prove citizenship of the country, if need be. Yet, there is no one to piece together the events that brought about this resettlement card. While chote dad, now 91, lives in America, distance and his hearing troubles make communication impossible. Moreover, his memory seems to have developed gaps. When my brother visited him last year during a work-trip to US, chote dad could not recognise him; he had forgotten the very existence of my brother. He remembered all other things and family members, up until his last visit to my home in Delhi in 2012.

I turned to my father, who’s volunteered to be keeper of micro-histories. It was still the old narrative: “shifted before the Partition; don’t know about how they came”. “Any memories of Partition flare-ups that they relayed?” I asked. He went on to describe his mother’s aunt, who belonged to an extremely wealthy family that “kept arab ki ghodey (Arabian horses)” in those times, and was consequently, more vulnerable in the time of communally motivated loot and rioting. “The women all jumped into the well in the house and the aunt somehow remained close to the surface instead of drowning”. He began to well up. “Amid the fleeing and destruction, her Muslim servant spotted her, rescued and shielded her in his house for a long while,” he choked on his words. She was reunited with family when the military came on its rounds to find people left behind. I knew it was the end of recollections for now.

I picked up one of dad’s scribbling diaries, that he used to keep until he passed away a decade ago. Among the pages filled with details of the electricity metre, birth dates of family members and favourite lines from the Bible, Gita or Quran, a page was titled ‘Anti-depression measures’. There were seven pointers. I never knew this person or what his mind was battling. I only knew the one who’d wear a smile and quote Iqbal: “Khudi ko karr buland itna, k har taqdeer sey pehley khuda bandey sey khud poochey, bataa teri razaa kya hai” (Develop the self so, that before every decree

God will ascertain from you: “What is your wish?”)

Akshita Nagpal is a New Delhi-based multimedia journalist who has written for The Caravan, The Hindu, Deccan Herald and Kafila amongst other publications and has shot non-fiction films for digital portals.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.