Before Warsaw’s Children Were Sent to Their Death, They Performed a Play by Rabindranath Tagore

May 9 was Rabindranath Tagore's birth anniversary.

The destruction of Europe’s Jews picked up momentum after the Wannsee conference of January 20, 1942. The Treblinka death camp, located just 50 miles north-east of Warsaw, was the Nazis’ camp of choice for deportations out of the Warsaw ghetto. Commissioned in early July, 1942, Treblinka became fully operational on July 23. By August 5, it had murdered over 97,000 Warsaw ghetto deportees. Then, on Thursday, August 6, Treblinka received its largest-yet human cargo of 10,085 ghetto inmates and, by the next day, dispatched all of them to their death.

Among the victims that day were about 200 child orphans and the director of the orphanage they came from – Janusz Korczak. But the grisly end to their lives is not why we remember these luckless kids and their intrepid mentor today, but something they had all been part of only a few days prior to their death. An event that invests these destroyed lives with a rare dignity, a poise scarcely associated with the victims of a genocide. The anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore’s birth is as good a time as any to look back to that extraordinary event – not least because the event in question pivoted around a play written by the poet.

Sunday, July 19, 1942 saw Janusz Korczak’a wards at the Dom Seirot orphanage in the Warsaw ghetto stage a production of Rabindranath’s 1912 play Dakghar (The Post Office).

Dakghar tells the story of Amal, an incurably sick child languishing in the home of his adoptive uncle, in the final days of his tragically short life. The doctor has decreed that Amal mustn’t leave his room or be exposed to sunshine or rain, lest his chances of recovery should recede even further. But the world outside, with its multitude of sights, sounds and smells, beckons to Amal all through the long autumn’s day, powerfully, irresistibly. He sits at his tiny window, making friends with whoever happens to pass by: kids his age playing merrily at their many games; an itinerant dairyman vending his wares; the comically self-important village watchman; a loquacious little flower girl; the bumptious village headman throwing his weight around endlessly.

Of everyone he meets, Amal eagerly enquires where they come from, what their life is like, and what kind of people they get to meet in course of their day. There is also the wandering Fakir, the man after the child’s heart, who weaves tales of wonder and beauty, half real, half imagined, about far-away lands, deeply stirring Amal’s lively imagination and filling him with longing for the unknown and the unseen. The boy dreams of a letter the king will some day send him through a new post office coming up acroos the road to his window, and asks everyone about that letter. Some mock his naivete, others feel sorry for him. But, as disease takes hold of him completely and he begins to sink, the king’s herald arrives with word that the king himself planned to visit Amal later that night and had meanwhile sent the royal physiciam to check on his young friend’s health.

Unlike the village doctor who had quarantined Amal, the noble physician throws open every window and every door of his room so that starlight and sweet air can enter it freely. Comforted and happy, Amal drifts into peaceful sleep, never to awake again.

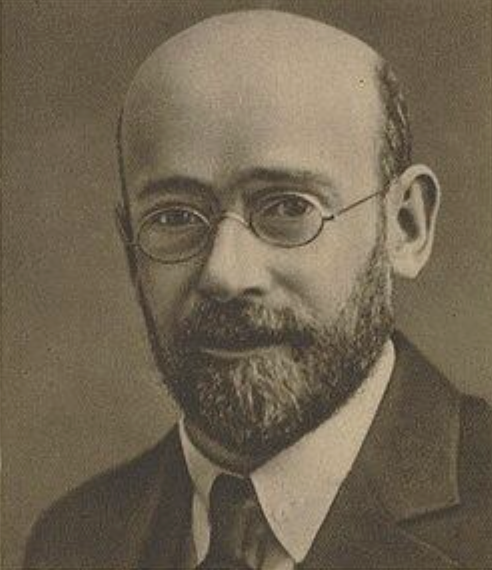

Janusz Korczak.

“Amal represents the man whose soul has received the call of the open road," Rabindranath wrote once. For the orphans of Dom Seirot, that call of the open road must have come via The Post Office as a rare call to freedom.

Shut in within the cruelly narrow limits of the ghetto where over 450,000 humans had been squeezed into a mere three square kilometres of living space; dogged daily by food shortages and with precious little access to decent healthcare; and, perhaps most crucially, weighed down by anxiety about the future – Janusz Korczak's children could readily identify with Amal as he yearned to touch, with his hands and his eyes, the wide world outside his claustrophobic little room. The simple story-line and the lyrical tone of its telling couldn’t have failed to move both the actors and the audience.

No one at that point could have known what fate awaited them less than twenty days later, but it’s a fair guess that, for many of those present at the performance that summer evening in Warsaw, The Post Office was as a breath of fresh air, a deliverance, however evanescent, from the crushing hopelessness that had come to define life at the ghetto.

I don’t think Korczak made it known why he had selected Dakghar, and not some other play, for that Sunday evening’s programme. His diary – at any rate the diary entries made around that date – provides no clue, though it does speak about the evening with Korczak's trademark wry humour:

The next day, that was yesterday – the play. The Post Office by Tagore. Applause, handshakes,smiles, efforts at polite conversation. (The chairwoman looked over the house after the performance and pronounced that though we were cramped, that genius Korczak had demonstrated that he could work miracles even in a rat hole.)

That is why others have been allotted palaces.

Korczak with his kids and colleagues before the war. Photo: Public domain.

Rabindranath Tagore’s was surely not an unfamiliar name in Poland.

He had been widely translated into Polish, with The Post Office claiming the distinction of having been translated the most – five – times. That being so, Korczak, a distinguished writer himself of both juvenile fiction and non-fiction, could scarcely have been unfamiliar with the poet’s work. The Post Office, therefore, could only have been an informed choice for a stage production and not a random one.

Indeed, I will argue that Korczak selected a play by Tagore because there were several important points at which Korczak’s world view converged with Tagore's. For one, both were secular humanists. And for another, both remained unapologetically non-conformist all their lives. Though born Jewish, Korczak was not religious, much less a Zionist, although he suffered immeasurably on account of his Jewish identity, both during the war and in the immediate pre-war years.

A well-known paediatric doctor, he lost his position on major Warsaw hospitals because he was a Jew; his very popular weekly programme on Warsaw radio was abruptly shut down; and he was eased out of the directorship of a major non-Jewish orphanage which he had helped build and grow. At the same time, he wrote in Polish, not in Hebrew or Yiddish, annoying Zionists no end. And though he visited Palestine a few times while on vacation – and greatly liked the idea of living on a kibbutz – he never contemplated leaving Poland for Israel/Palestine. Korczat was a reformer, an ardent socialist in his sympathies, not a conservative traditionalist. Like Rabindranath Tagore in far-away India, he often found himself at odds with his social and intellectual environment.

Korczak's children in happier times. Photo: Public domain.

And perhaps there was an even deeper affinity between these two men. Both were indefatiguable champions of children’s rights. A Korczak orphanage was modelled on a ‘people’s republic’: it had its own mini parliament where the inmates legislated on the do’s and the don’ts, the rights and the duties for all residents; it had its tiny court adjudicating and settling disputes; it had a library, an orchestra and a theatre group of its own.

As early as in 1919, in his well-known book titled How to Love a Child, Korczak proposed that the three basic rights every child was entitled to were: the right of today (or the right of every child to be respected for what it is, and not just as a future adult); the right over its own death; and the right of the child to be what it wants to be.

As far ahead of its time as this vision was, this charter of children’s rights would, one suspects, have earned unqualified approbation from Tagore who had built his own Santiniketan school on the model of a self-governing children’s society underpinned by defined rights and bolstered by defined responsibilities which no adult could challenge.

The play Dakghar foregrounded the poet’s recognition that not only a child had as much right to know the world as any adult, but also that, in a very real sense, it might actually know more about the essence of life than adults gave it credit for. Korczak, who never married or had children of his own, lived only for his children. He had given up his flourishing medical practice so he could give his orphanages his undivided attention, though he continued to write his hugely popular children’s fiction till very nearly the end. When the ghetto was built and the orphanage was obliged to move out of its roomy Warsaw city premises and into its cramped new quarters inside the ghetto, he insisted on moving in, too, though, as a widely-respected man whom practically everyone knew, he had the option of staying back. May be it was then that he wrote: “You do not leave a sick child in the night, and you do not leave children at a time like this”.

I have little doubt that Janusz Korczak selecting Dakghar for a production to be mounted by his children in the shadow of impending disaster could not have been fortuitous.

A memorial plaque in Warsaw. Photo: Public domain.

Running an orphanage for Jewish children inside the ghetto was a daily struggle and incredibly more so as the ‘final solution’ began to play out. Supplies were growing more scarce by the day even as new orphans needed to be taken under Korczak’s wing with never-failing regularity: adult death from starvation, malnutrition and infectious disease was rampant in the ghetto. And yet Korczak and his small team of dedicated child activists defied every odd to try and shield the children from the worst for as long as possible. As the deportations to the death camp – euphemistically referred to as ‘transfer to the East’ by the Nazi authorities – began in deadly earnest in the third week of July, 1942, however, they sensed they would have reached the end of the road.

It was probably late on August 5 (or early on August 5) that Korczak was notified of the ‘transfer’ of the children scheduled for the next day. At that point the Polish Resistance in Warsaw again sent word to Korczak that they were prepared to smuggle him out to safety. Korczak declined. He couldn’t very well abandon his children to their fate when they needed him most. He would stay with them for as long as it was possible to do so.

On August 6, 1942, Korczak and his colleagues walked the children – between 192 and 196 of them – to the designated pick-up point at the ghetto’s northern exit. Extant accounts of that final journey differ wildly from one another. Some have the children turned out in their best clothes, walking cheerfully through the ghetto’s centre, with Korczak calmly helping two tiny tots along with his two hands. Some other witnesses draw a bleak picture of bewildered kids dragging themselves along, as Korczak, his head bowed and his eyes averted, trudged on in their midst together with his other colleagues. That was the last the world saw of Korczak and his children.

Korczak and his children, at the road’s end. Photo: Public domain.

The night after his children had staged The Post Office – Korczak was to turn 64 the next day – his diary entry read:

It’s a difficult thing to be born and to learn to live. Ahead of me is a much easier task: to die...I should like to die consciously, in possession of my faculties. I don’t know what I should say to the children by way of farewell. I should want to make clear to them only this – that the road is theirs to choose, freely.

Here was a man, weary to the bone, contemplating death -- his own. But he still hoped, even as the shadows of hell were about to shroud his world, for his children to be able to walk a road after their own hearts – a road whose call had been brought to them by a child like themselves, like themselves an orphan: Amal of The Post Office. In the event, though, his children’s road ended, together with Korczak’s own, at Treblinka’s gas chambers. The day was August 7, 1942.

That was one year to the day after the poet who wrote The Post Office had passed on.

Anjan Basu can be reached at basuanjan52@gmail.com.

This article went live on May tenth, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-six minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.