Remembering Subhas Chandra Bose’s Strong Views Against Hindutva Politics

Kolkata: ‘Netaji’ Subhash Chandra Bose’s stinging indictment of Hindutva politics in a May 1940 speech in West Bengal’s Jhargram has been back in the discussion in Bose’s home state over the past few years. To be precise, a few lines from it.

The lines are: “The Hindu Mahasabha has sent monks and nuns with tridents in their hands begging for votes. Hindus bow in reverence at the very sight of trident and saffron robes. Hindu Mahasabha has entered politics by taking advantage of religion and has desecrated it. Every Hindu needs to condemn them.”

This part of his speech, in its Bengali original as well as English translation, has been doing the rounds on social media for the past few years. However, many started doubting its authenticity after Netaji researcher Chandrachur Ghose, in a social media post on January 24, 2022, cast doubts on the authenticity of the comment.

“This is how myth is created. Create a template of false propaganda and party workers will circulate. No one can/will produce the originals. Bose's collected works don't have it. I have checked Jugantar of that date. No news. Prime example of Left-Congress fakery,” he wrote in the post, in which Ghose also ‘tagged’ authors Vikram Sampath, Anuj Dhar and Kapil Kumar.

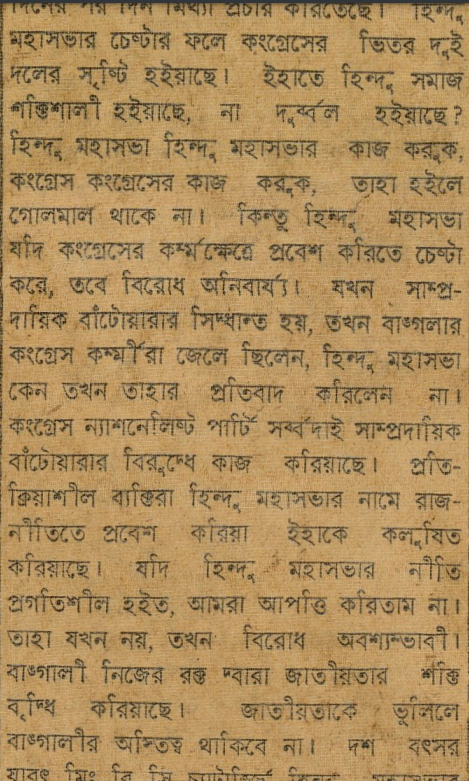

Prompted by requests from several persons for a fact-check, this journalist accessed the Anandabazar Patrika of May 14, 1940. Most of the social media posts using the comment had mentioned the date and the newspaper. A look at page 7 of that day’s Anandabazar Patrika, confirmed that the quotation in circulation is verbatim.

Subhas Chandra Bose's speech targetting Hindu communal politics published in May 14, 1940 edition of Anandabazar Patrika. Photo: Special Arrangement | Anandabazar Patrika

The speech of the May 12, 1940 meeting was published in the May 14 edition of the newspaper. On the 12th, a Sunday, Bose held organisational meetings at Jhargram town and then gave a speech at the Lalgarh ground for two hours and a half.

After this journalist pointed out in an article in Anandabazar Patrika’s April 13 issue how Bose’s comments were not only authentic but also consonant with his larger politics, Ghose admitted his mistake in a social media post.

“I was wrong about this, as despite several attempts I couldn’t find the report. However my central argument remains unchanged,” he wrote in a post.

In another, he wrote that “TMC & Left supporters… are entitled to be happy in their ignorance, but I reiterate that this in no way affects the facts I have presented & arguments I have made in ‘Bose’ & later. I stand by my analysis & interpretation of facts.”

While the authenticity of one single quotation should not, indeed, be treated as the basis of a researcher’s central arguments, it might be difficult for anyone other than Ghose to succinctly describe his “central arguments” or what his “analysis and interpretation of facts” exactly reveal in gist.

One of the points he stressed in his past work is that Bose, though critical of Hindu Mahasabha leader Vinayak Savarkar’s politics, held respect for the latter.

“Subhas Chandra Bose wasn’t ‘anti-Savarkar’,” Ghose claimed, adding, “Not only was the relation between Bose and Savarkar much more nuanced, but they also held each other in high regard despite their political differences.”

Personal respect may be a sphere of speculation but that Bose opposed communal politics, particularly those preached by Savarkar’s Hindu Mahasabha and Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League, is irrefutable.

The May 12 speech makes it clearer. He blamed Savarkar alone for the breakdown of the Congress’ alliance initiatives with the Hindu Mahasabha for Kolkata’s municipal elections in 1940.

In that speech, Bose also urged people to boycott Amritbazar Patrika and the group’s Bengali publication Yugantar, besides publications named Bharat and Matribhumi. They were “spreading lies day after day”, Bose alleged.

The call for boycotting four newspapers was based on his allegation that they were harming national unity efforts. Bose argued that at a time the Congress managed to wean the Muslim League away from Europeans in governing the Calcutta Municipal Corporation (CMC), which showed that Hindus and Muslims could together govern the country without the British, these pro-Hindu Mahasabha media constantly opposed the efforts.

This acrimonious relation might be why Ghose could not find Bose’s speech in that day’s Jugantar.

Some of the social media posts highlighting Bose's May 12 comments also include two more sentences — "Banish these traitors from national life. Don't listen to them." Bose did not say this referring to the Hindu Mahasabha. Here, he was referring to the right-wing section of the Congress — or the Congress high command of the time — that had "imposed" an "ad-hoc committee" on the Congress' Bengal unit in February 1940 amidst the heightening Bose-Gandhi conflict.

Unambiguous position

During the Lalgarh speech, Bose explained the Congress policy towards communal organisations. Referring to the Hindu Mahasabha and the Muslim League, he said, “None of them are our enemies, all the countrymen are our allies. Foreign imperialism is the only enemy.”

Bose explained that the Congress tried to reconcile with the Hindu Mahasabha (in March 1940) adhering to the party’s policy but “Savarkar ordered against any understanding with the Congress. That’s why the coalition efforts with the Hindu Mahasabha broke down.”

After this, when Congress found common ground with the Muslim League in municipal governance, they joined hands with the League. The main objective was to keep the British away from the municipality. Bose was keen on using municipal governance for mass contact.

In the May 12 speech, he asked, “The Hindu Mahasabha’s efforts have divided the Congress into two groups. Has it strengthened the Hindu society or weakened it?”

Bose said there would be no conflict if the “Hindu Mahasabha does Hindu Mahasabha’s work and the Congress does Congress’s” but “conflict is inevitable if Hindu Mahasabha tries to enter the Congress’ field.” By Hindu Mahasabha’s work, he meant religious work.

He alleged that “reactionary people” had entered politics in the name of Hindu Mahasabha and vitiated politics. He said, “Had the policy of Hindu Mahasabha been progressive, we would not have objected. When it is not, conflict is inevitable. Bengalis have strengthened nationalism with their own blood. Bengalis will cease to exist if they forget nationalism.”

Such an attack on the Mahasabha did not come out of the blue. The tempo had been rising since December 1939, when Vinayak Savarkar came to Kolkata to strengthen the Bengal unit of the Hindu Mahasabha. Bose had by that time launched the Forward Bloc within the Congress with the call for intensifying the freedom movement.

The 30 December 1939 issue of the weekly publication Forward Bloc, which he edited, strongly criticised Savarkar’s speech in Kolkata, saying it involved “tub-thumping” and “ill-laid emphasis.”

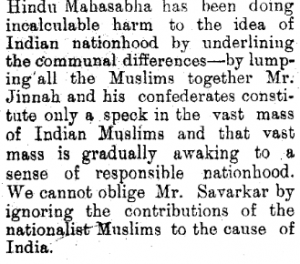

From December 30, 1939 issue of Forward weekly, which Subhas Chandra Bose edited. Photo: netajisubhas.org

The Hindu Mahasabha had been doing “incalculable harm to the idea of Indian nationhood” by highlighting communal differences, by “lumping all Muslims together,” it alleged.

The article called the Muslim League “rancorously mean” and the Mahasabha “raucously outrageous”. It was argued in the brief report that Congress had repeatedly tried to strengthen the national movement by engaging with both the Muslim League and the Hindu Mahasabha but these communal organisations spoiled such attempts.

“Mr. Jinnah and his confederates constitute only a speck in the vast mass of Indian Muslims and that vast mass is gradually awakening to a sense of responsible nationhood. We cannot oblige Mr. Savarkar by ignoring the contributions of the nationalist Muslims to the cause of India,” it said.

Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s accounts reaffirm Bose’s position as reflected in the previous paragraph. Mookerjee wrote, “Subhas once warned me in a friendly spirit, adding significantly, that if we proceed to create a rival political body in Bengal, he would see to it (by force if need be)... that it was broken before it was really born.”

Mookerjee – who later founded the BJP’s ideological-organisational predecessor, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) – considered it to be the “most unreasonable and unfair attitude to take up.” But Bose had decided to take communal forces head-on.

Bose’s philosophy has been the complete polar opposite of Hindutva's thinking. In this regard, he followed his Guru, ‘Deshbandhu’ Chittaranjan Das and Gandhi – both high priests of communal unity. Bose differed with Gandhi on the course and strategy of the national movement but not the nature of India. All of Das, Gandhi, Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru considered Muslims as integral to India and the British rule as the beginning of India’s subjugation.

In sharp contrast, in the last ten years, Prime Minister Narendra Modi repeatedly spoke of ‘thousand years of slavery’, in an obvious reference to the entire chapter of Muslim rulers “as subjugation” or “foreign rule.” This is the last remark Bose would have approved.

In an editorial titled ‘Towards Communal Unity’ published in the Forward Block weekly on 24 February 1940, Bose wrote, “Communalism will go only when the communal mentality goes. To destroy communalism is, therefore, the task of all those Indians – Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, Christians etc., who have transcended the communal outlook and developed a genuine nationalist me mentality.”

Bose’s work and words reflect a nationalist to the core of his heart. To him, the national interest of throwing out foreign power was of greater value than any other internal conflict of Indians. He tried to unite the whole of India cutting across religion, caste, and class lines. He criticised all forms of sectarian politics. He thought, every other internal conflict could wait and would be easier solved in a free India.

Also read: Modi's Portrayal of Netaji as a Hindu Militarist Does the Secular, Socialist Bose a Disservice

It is his one-point agenda of liberating India from foreign powers that led him to collaborate with Hindu Mahasabha and/or Muslim League in the early 1940s and to ally with the Axis Powers during WWII after his Great Escape.

As is well-known, before his internment in July 1940, Bose met both Savarkar and Jinnah. He offered Jinnah the post of independent India’s first prime minister in exchange for the League’s support of his movement. He found Jinnah to be preoccupied with the idea of Pakistan. Savarkar was, in Bose’s words, “seemed to be oblivious of the international situation and was only thinking how Hindus could secure military training by entering Britain’s army in India.”

Bose realised that nothing could be expected from the Muslim League or the Hindu Mahasabha for the country's freedom.

In his August 17, 1942 speech on Azad Hind Radio, Bose described Savarkar and Jinnah as “leaders who still think of a compromise with the British”. He said, “The supporters of British imperialism will naturally become non-entities in a free India.”

Bose may have been a little wrong in this assessment. Jinnah’s supporters among Indian Muslims may have deserted India at the time of Partition with their own parcel of land, but Savarkar’s supporters are now running the country, ironically trying to appropriate Bose’s legacy.

This article went live on April fifteenth, two thousand twenty four, at fifty minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.