Why India Must Make the Roy Bucher Papers on Kashmir Publicly Accessible

Last week, The Guardian published a story about the Indian government’s unwillingness to grant researchers access to a set of files relating to developments in Jammu and Kashmir during the years 1947 to 49 – the turbulent period before and after its accession to the Indian Union.

The records in question were handed over by Sir Roy Bucher, the second and last British Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, to the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML). As NMML has stored them in its “closed” category of manuscripts, they are not accessible to any researcher.

I know this for a fact because my RTI intervention to make them publicly accessible is also mentioned in passing in The Guardian story.

The reporter said she had spoken to an unnamed government source who appeared to be privy to the contents of some of these papers.

She was told that the Ministry of External Affairs is reluctant to drop the “closed” tag fearing probable adverse impact on India’s international relations. The papers also contain correspondence between high level government functionaries (and we know this for a fact from publicly available documents) whose sensitivity apparently remains undiminished even after the passage of more than seven decades. This despite the NMML head’s supposed recommendation to the government to throw open these papers to researchers.

While this seemed like yet another news report about the tendency of government to err on the side of secrecy instead of transparency, one scholar was quick to note that Bucher's papers have been available at the National Army Museum, London, for a long time and chided The Guardian for not knowing better than to publish its story. Another scholar tweeted that he had read scholarly works citing these papers and accused The Guardian of "careless reporting which could help bigots". Others joined the fray, claiming the news report was politically biased.

The accusations were unnecessary because the issue at the heart of The Guardian story is quite simple: Shouldn’t the Bucher papers held in India be available to researchers in India so that those who cannot afford – or have no desire – to travel to London may access them?

General Sir Francis Robert Roy Bucher, Former Commander-in-Chief, Indian Army. Photo: GODL-India

Who was Sir Roy Bucher?

Francis Robert Roy Bucher was born in North Leith, Edinburgh on 31 August, 1895. He studied at the Edinburgh Academy and was commissioned from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst as a Second Lieutenant in the Indian Army in 1914.

According to the profile of the Chiefs of the Indian Army published on its official website, Bucher saw action during both world wars. After World War II, he was appointed General Officer Commanding, Bengal and Assam Area and later posted as the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Eastern Command in 1946. He was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army in January 1948 and served until 15 January, 1949.

He was awarded the Military Cross for his services during World War I and made a Companion of the Order of the Bath and later Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire. His first wife, Edith Margaret Reid, died in Bangalore in December 1944. Later he is said to have married Maureen Helen Susan Gibson in Calcutta in February 1946. Sir Roy Bucher passed away in 1980.

The story of the quest for the Roy Bucher papers

Readers will remember my article about J&K’s Instrument of Accession (IoA) published here in 2016. That article also raised quite a storm.

Some readers generously conferred on me the title “Pakistani agent” simply because the contents of the multi-colour electronic copy of the IoA accessed from the National Archives of India (NAI) matched with a re-typed version published on some website maintained in that country. I will respond to that criticism on an appropriate occasion this year.

While continuing my research on the circumstances surrounding J&K’s accession to India and its aftermath, I came across the name of Sir Roy Bucher in certain records in the NAI.

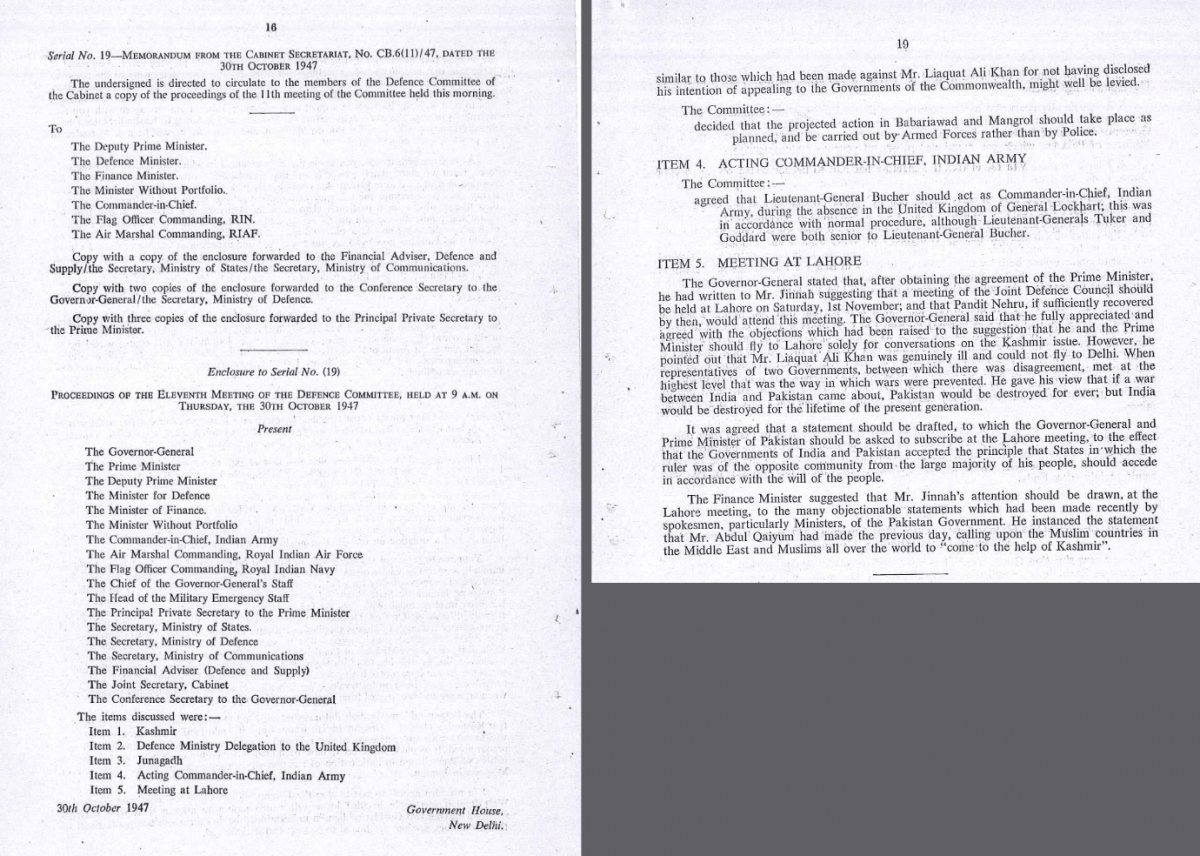

In the minutes of the meeting of the Defence Committee held on October 30, 1947 (when the battle to protect lives and property from invaders pouring into J&K from across the border was raging), Sir Roy was appointed to stand in for General Sir Robert McGregor Macdonald Lockhart – independent India’s first Army Commander-in-Chief, who was to travel to the UK. Interestingly, the committee made this choice over two other Lt. Generals – Tuker and Goddard – who were senior to him.

The reasons for this selection are not mentioned in those minutes. These and other related documents are also available on microfilm at NMML in the collection known as the Lord Mountbatten Papers, a subject to which I will return in the concluding section.

Extracts from the minutes of the Defence Committee’s meeting held on October 30, 1947.

After discovering that several files relating to J&K affairs from that era which originated in the ministries of Home, Defence, States and External Affairs had not yet been transferred to NAI, I decided to move my search to NMML, whose catalogues are publicly accessible on its website. The paper-based index of manuscripts in NMML’s holdings is accessible to any researcher on demand.

In this manuscript index, I spotted an entry about an interview of Sir Roy Bucher conducted by the noted biographer B.R. Nanda. The date of the interview is not known, nor is its provenance mentioned in the document. From a reading of its text, one gets the impression that the interview was conducted in India during one of Sir Roy’s visits after his retirement. In two places, Sir Roy mentions some papers relating to the J&K operations of 1947-48 and the related correspondence with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, which he had handed over to NMML.

Referring to this file, Bucher tells Nanda:

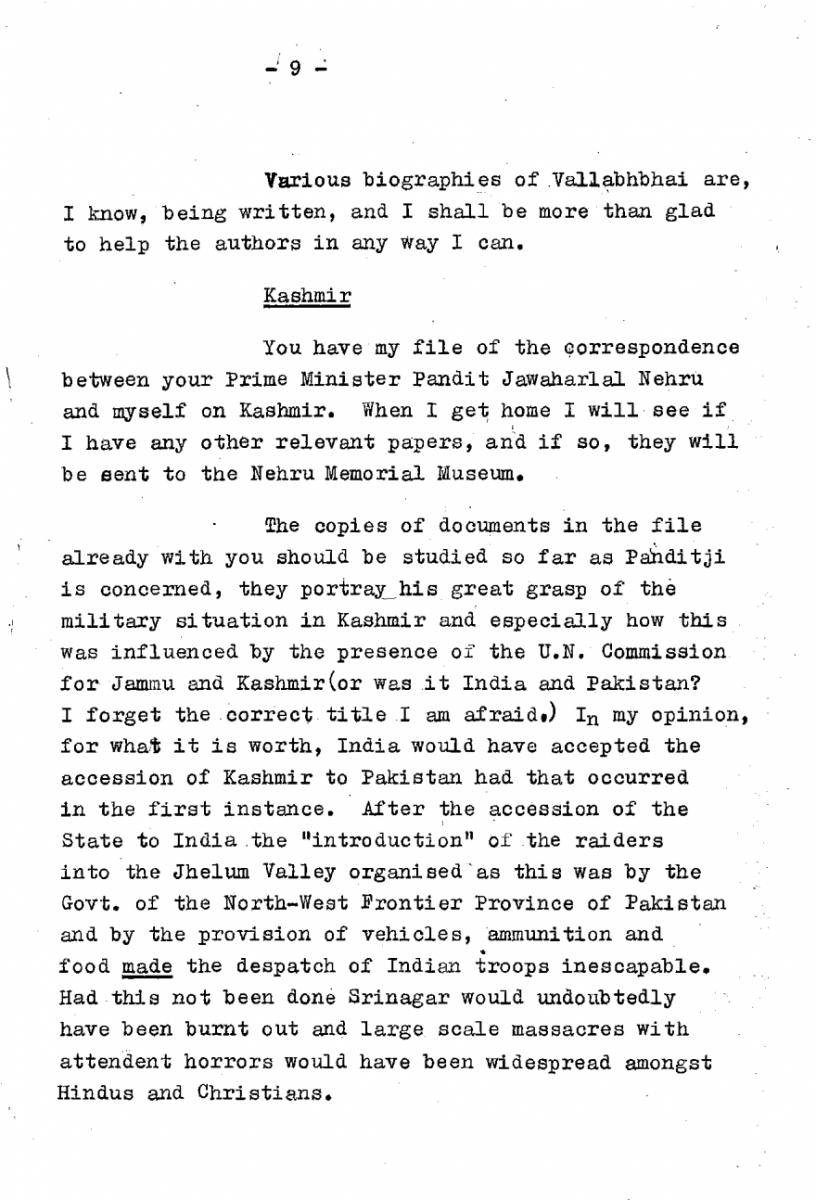

Photo: Extract from the record of Sir Roy Bucher’s undated interview conducted by B.R. Nanda.

“You have my file of the correspondence between your Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and myself on Kashmir. When I get home I will see if I have any other relevant papers, and if so, they will be sent to Nehru Memorial Museum.

"The copies of documents in the file already with you should be studied so far as Panditji is concerned, they portray his great grasp of the military situation in Kashmir and especially, how this was influenced by the presence of the UN Commission for Jammu and Kashmir (or was it India and Pakistan? I forget the correct title, I am afraid). In my opinion for what it is worth, India would have accepted the accession of Kashmir to Pakistan had that occurred in the first instance. After the accession of the State to India the “introduction” of the raiders into the Jhelum valley organised as this was by the Govt. of the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan and by the provision of vehicles, ammunition and food made the despatch of Indian troops inescapable. Had this not been done Srinagar would undoubtedly have bene burnt out and large scale massacres with attendant horrors would have been widespread amongst Hindus and Christians.”

Later on in the interview, Sir Roy refers to more papers he had handed over to NMML:

“…In one of his letters Panditji wrote:

“I do not know what the United Nations” I am quoting – “are going to propose. They may propose a cease-fire and what the conditions are going to be I do not know. If there isn’t going to be a cease-fire, then it seems to me that we may be faced with an advance into Pakistan and for that we must be prepared.”. I assured my Prime Minister that all steps would be taken to meet any eventuality; the next happening, so far as I was concerned, was when Sardar Baldev Singh” [the then Minister for Defence] “rang me up on the phone and said” “Go ahead.” I asked: “Go ahead with what?”. He replied: “Go ahead with the cease-fire.” My reply was: “Well it is a jolly difficult job for me as a Commander-in-Chief to tackle and you have the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan in the country.”. The answer was that I had to go ahead. So I drafted out a signal to General Gracey, the Commander-in-Chief in Pakistan; a copy of this is I know, in the file in the Museum now…”

Extracts from the record of Sir Roy Bucher’s undated interview conducted by B.R. Nanda.

NMML’s policy does not permit more than a third of the total length of such manuscripts to be photocopied. So, I sought copies of only four pages of relevance to my research which are reproduced above.

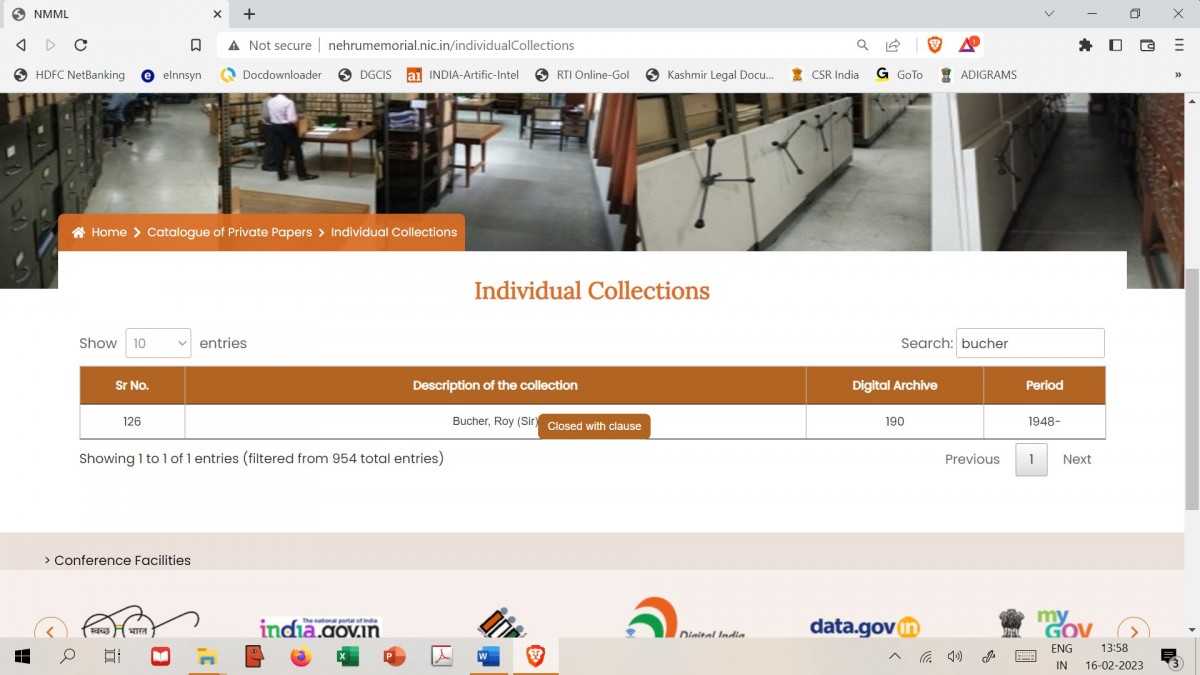

The next step was to look up another catalogue of manuscripts for the papers that Sir Roy Bucher said he had handed over to NMML. The catalogue entry mentioned that these papers were “closed” for public scrutiny. NMML staff manning the manuscripts section confirmed that I cannot access the Bucher Papers because of the Union government’s instructions to keep them confidential. At the time of writing, NMML’s online catalogue also confirms the “closed” status of the Bucher Papers.

Photo: Screenshot of the NMML online catalogue indicating the “closed” status of the Bucher papers.

The RTI interventions

Here was a challenge.

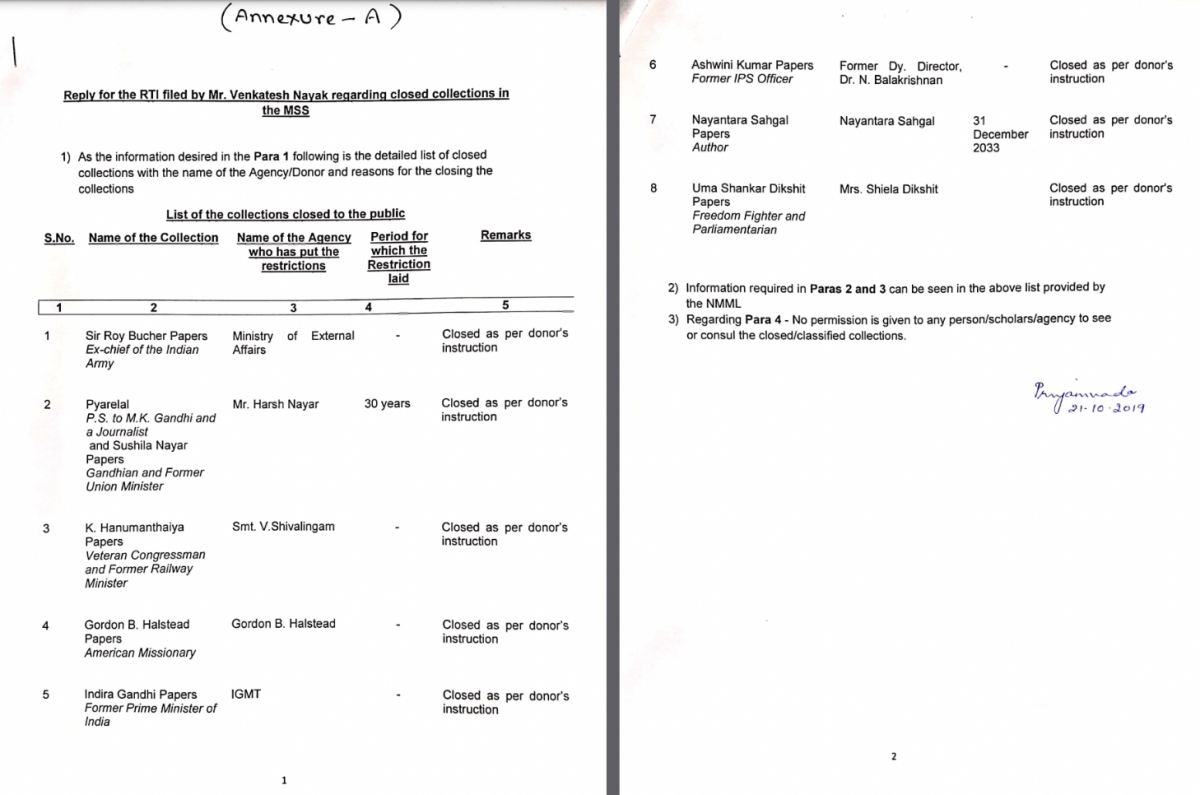

Sir Roy told Nanda that the papers he had handed over to NMML must be studied. How does one study them if access is denied? So, in October, 2019, I submitted an online RTI application to NMML seeking the complete list of documents and records that are closed to the public under instructions from any government agency; the date of their receipt at NMML; the name of the agency which issued such instructions and the period for which confidentiality of the records are to be maintained as per such instructions. I also sought inspection of the Bucher Papers for a period of five hours with an additional request to make arrangements to supply copies of the documents that I would identify during the inspection.

Within 20 days of receiving my RTI application, NMML’s Central Public Information Officer (CPIO) replied that no permission may be given to any person/scholar/agency to see or consult the closed/classified collections i.e, the Bucher Papers in this case.

The CPIO also supplied a list of papers that were closed for public scrutiny which include the papers of Mahatma Gandhi’s Private Secretary, Pyare Lal, former Prime Minister Smt. Indira Gandhi, noted author and niece of Pandit Nehru Nayantara Sahgal, former Chief Minister of Karnataka Kengal Hanumanthaiah, former Governor of Karnataka Umashankar Dixit, an American Missionary Gordon B Halstead- and a former IPS Officer, Ashwini Kumar. Informal chats with NMML staff before the RTI intervention was made had revealed that their own catalogue of archival papers that are in the “closed” category was under compilation and in no way complete.

The Bucher papers figure on top of the list which NMML supplied under RTI and the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) is shown as the agency which put the restrictions on public access. However, in the remarks column it is mentioned that the papers are “closed as per donor’s instruction.”

This claim runs contrary to what Sir Roy said in his interview with Nanda – that he wanted the papers he had handed over to be studied. Surely, he was the donor and not the MEA. Unless a covering letter under his name and signature seeking confidentiality for these papers is produced, the contradictions between what he said in the interview and NMML’s claims will remain unresolved.

Photo: Extract from the RTI reply received from NMML’s CPIO in 2019.

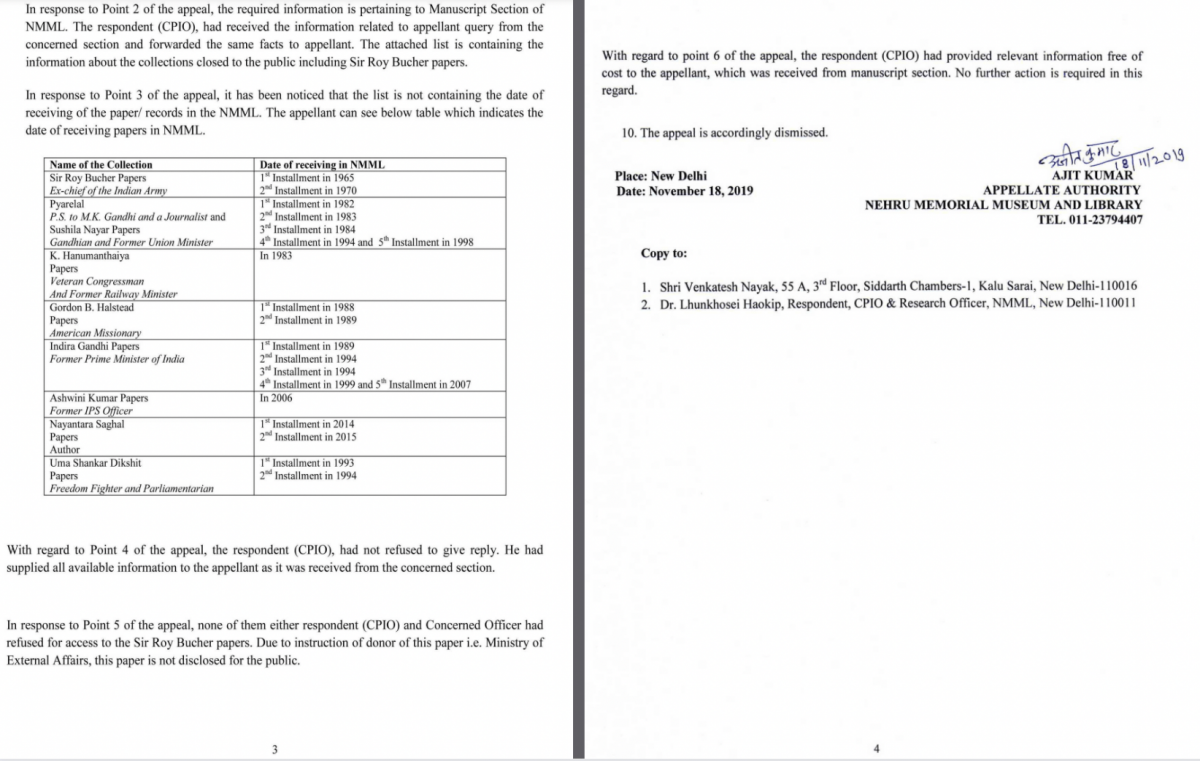

Dissatisfied with NMML’s reply, I filed an appeal challenging the refusal to allow inspection of the Bucher papers and the absence of dates on which the archival documents closed to the public were received in their holdings. NMML’s First Appellate Authority (FAA) dismissed the appeal stating that the CPIO had not rejected access to the Bucher Papers under the RTI Act by invoking any of the permissible exemptions.

Instead, access was being denied as per instructions of the 'donor', namely the MEA. The FAA also provided a list of dates on which the papers “closed” to the public were received from the donors. Sir Roy is said to have handed over his papers to NMML in two instalments – in 1965 and 1970.

Photo: Extracts from the order issued by NMML’s FAA.

Aggrieved by the repeated refusal to permit access to the Bucher Papers, I submitted a second appeal to the Central Information Commission (CIC) in January 2020. Several grounds were cited in favour of disclosure. The CIC heard the case 21 months later, in September 2021 and directed NMML as follows:

“Keeping in view the facts of the case and the submissions made by both the parties, the Commission observes that the objective of the Appellant in National interest. Therefore the Commission directs the CPIO to take up the matter with the higher officials of the Respondent Authority and cite this order of the Commission and secure the necessary permission from them before sharing the information with the Appellant.”

During the hearing, in addition to several other grounds I had argued that the Union government had announced a policy decision in June 2021, to declassify documents relating to war and operations archives, so there ought to be no obstacle in allowing access to the Bucher Papers.

The CIC did not call for the papers to examine them for their sensitivity to make a determination about their disclosure in the larger public interest despite my specific prayer in the appeal. The Commission also passed the buck to NMML and MEA and merely aligned my arguments in favour of disclosure with what it deemed to be the objective of “national interest.” The CIC did not give NMML or MEA any timeline to comply or even report back on the action taken with its direction.

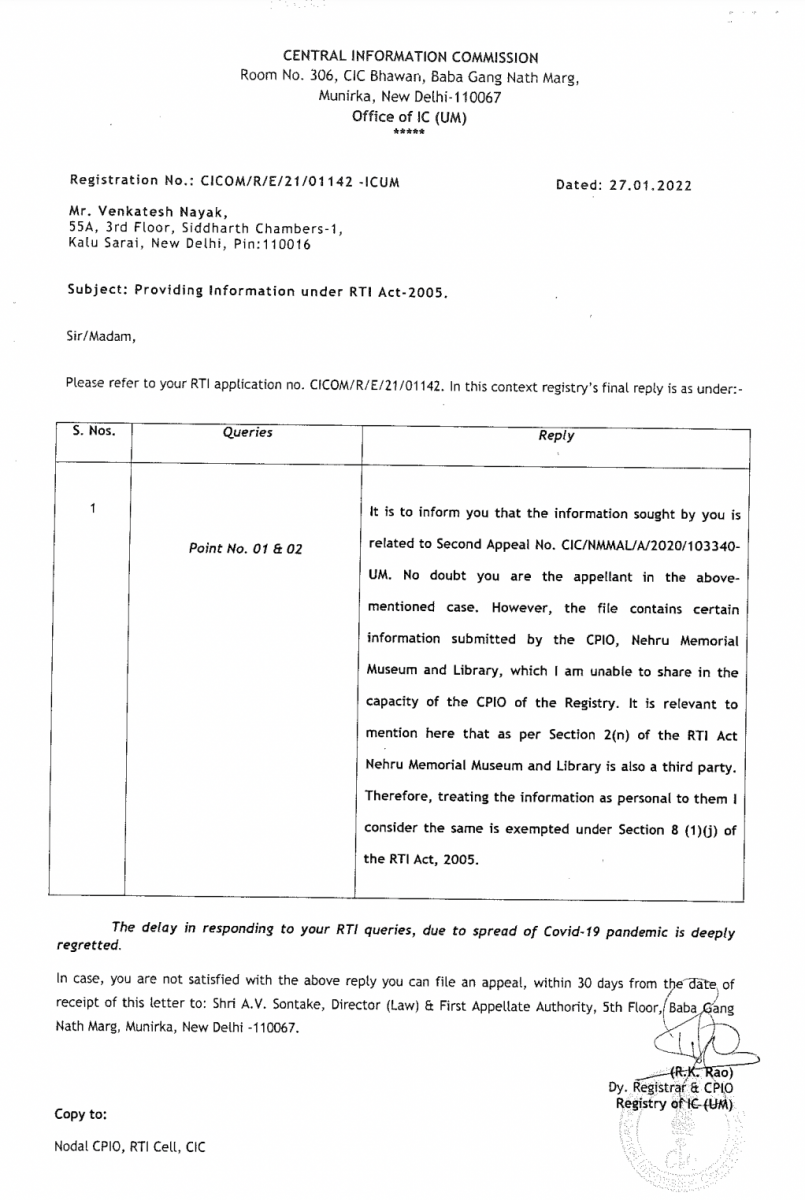

I waited for a response to the CIC’s order until December that year. As there was complete radio silence, I submitted a second RTI application, this time to the CIC, to inspect my case file. The CIC’s CPIO refused to permit inspection of my own file saying that it contained submissions from NMML. The CPIO treated NMML as a ‘third party’ and their submissions as information ‘personal’ to them and invoked the privacy exemption under Section 8(1)(j) under the RTI Act!

Photo: Copy of the rejection order issued by the CIC’s CPIO in January 2022.

I found the CPIO’s reply so stupefying that I did not even attempt an appeal against it. NMML being an autonomous institution under the Union Ministry of Culture has legal personality and can sue or be sued in a court of law. But to grant it the protection of privacy which is permitted only to natural persons under both the RTI Act and Article 21 of the Constitution amounts to misapplication of the fundamental right to privacy.

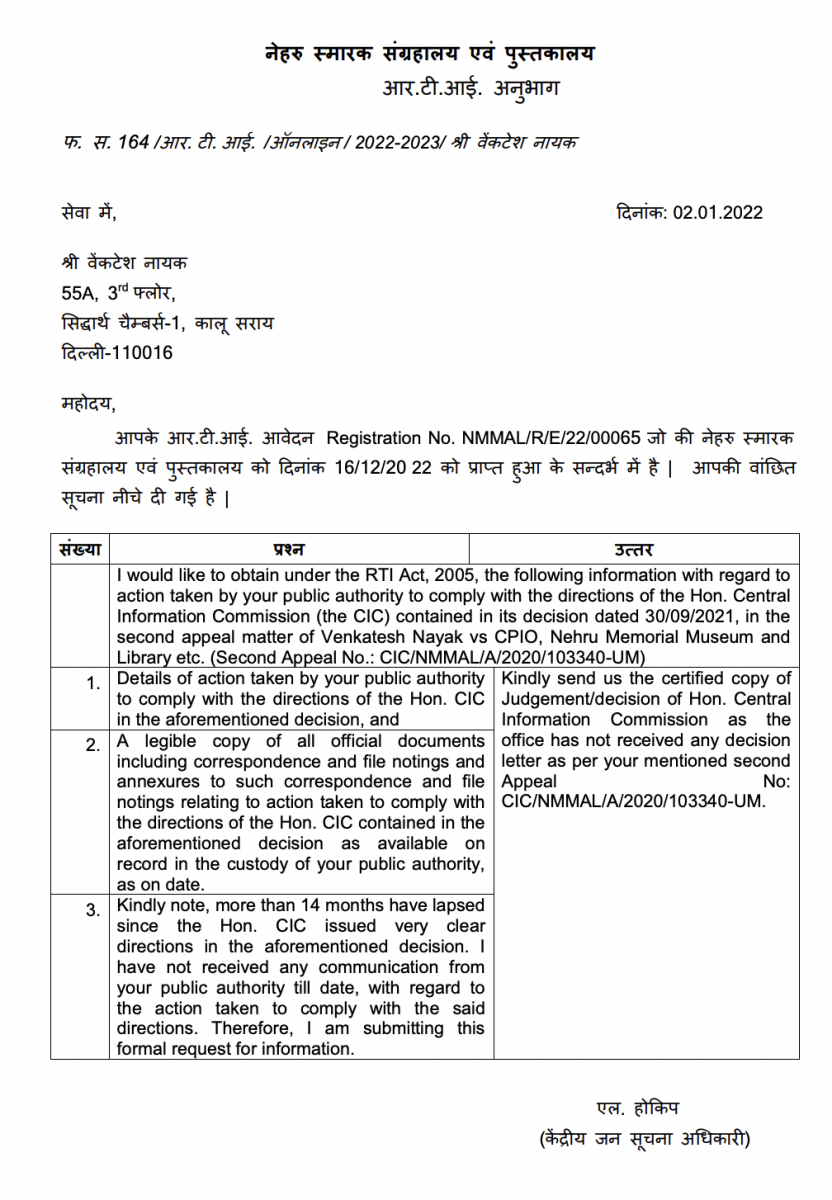

After waiting for more than a year for information regarding compliance, in December 2022, I filed an NMML RTI application with NMML, the third in this series, seeking details of action taken on the CIC’s direction to approach the MEA to open up the Bucher Papers.

Believe it or not, NMML’s CPIO claimed that they had never received a copy of the CIC’s order and that they would look at it if I were to be so kind as to send them a ‘certified copy’ of the same. The CPIO did not bother to sign the reply uploaded on the RTI Online Facility. I am still waiting for a signed copy to be delivered by post.

Photo: Copy of the NMML CPIO’s reply of January 2023.

As this matter seems to be moving rapidly into the theatre of the absurd, I have decided to entertain myself some more. So, another RTI application has been filed, the fourth in this series and the second with the CIC, seeking proof of despatch and delivery of its order to NMML. The CIC always sends its orders and hearing notices by Speed Post, so there ought to be a record of this information in its files. A reply is eagerly awaited.

So, to all those who noted, quite correctly, that the Bucher Papers are available in London’s National Army Museum, I would like to say that what the UK did for transparency is laudable but it is their business. Researchers in India surely deserve public access to records being held in our government’s locked-up almirahs. As taxpayers we foot the bill for the infrastructure set up to safeguard confidential documents; NMML and MEA are merely the custodians.

It is our fundamental right to demand access to documents that have a bearing on our past. The sparkling bauble called the Koh-i-noor or a king’s sword or exotic sculptures carved in stone or cast in metal alone do not make up India’s cultural heritage. Intellectual heritage is very much a part of that hoary legacy and it cannot be satisfactorily reconstructed when crucial source documents are lying under lock and key.

Some remaining questions

The Bucher Papers saga has thrown up several questions that need answers.

First, without examining the papers in NMML’s holdings, how can we pass judgment that they are merely copies of what is housed in London’s National Army Museum? Sir Roy himself was unsure if certain papers he mentioned in his interview with Nanda are in the files he handed over to NMML. He promised to go back home and double check if anything was missing. Granted, the National Army Museum might have a list of documents which were apparently shared with NMML. Is the list comprehensive enough to cover all papers handed over in 1965 and 1970? How do we know unless the two sets of papers lying thousands of miles apart are compared with each other?

Further, if some papers are accessible in a foreign country in offline mode, do they become accessible to everybody, everywhere? If that were the case, NMML ought not to have spent taxpayers’ money to microfilm hundreds of pages from the Lord Mountbatten Papers which form part of the Broadland Archives housed in the University of Southampton, UK and bring them back to Delhi. Scholars could have been left to fend for themselves using whatever means available to access those records in the UK. Interestingly, even NMML was not permitted to access some portions of the Mountbatten Papers relevant to India from the Broadland Archives, but that is another story.

Second, if Sir Roy gave the papers to NMML, when and how did they end up at the MEA’s door for a decision regarding public access? When Sir Roy is clearly the donor, does the MEA have the authority to bar disclosure to the public and why does NMML hold that the Papers are closed as per the donor’s instructions? Who instructed the maintenance of confidentiality? Sir Roy (highly unlikely as per his interview, plus the fact that some of his papers are accessible in London), or the MEA?

Third, which law, rule or regulation or executive instruction is the source of MEA’s power to bar access to the Bucher Papers? Is it the Manual of Departmental Security Instructions, 1966, used by every government office that stores “top secret”, “secret” and confidential” records? By the way, this Manual itself is a secret document and the CIC refused to direct its public disclosure in one of my failed RTI interventions. So, we do not know for sure how and by whom official documents may be classified and declassified.

Fourth, if the Bucher Papers have been accorded a security classification under this Manual, is it being reviewed by NMML every five years as per the statutory mandate under the Public Records Act, 1993 and the Public Records Rules, 1997. Is NMML sending an annual compliance report to the Director, National Archives of India (NAI)?

Fifth, who in the MEA overruled NMML’s reported recommendation to throw open the Bucher Papers to the public, if The Guardian report is an accurate account of the latest developments? The Papers are more than 70 years old. So the onus of proving that the sensitivity of the papers endures is a very heavy one and that burden must be discharged by the government to the satisfaction of the citizenry.

Sixth, contrary to what is reported by The Guardian, there is no 25-year or other time limit for declassifying sensitive documents that are labelled “top secret”, “secret” and confidential” by babus. Under the Manual of Office Procedure, the Union government is empowered to classify records in this manner till eternity or even destroy them without ever making them public. However, the RTI Act has an overriding effect on all these records maintenance practices to the extent of inconsistency. This is the unspoken basis of the CIC’s order to NMML to approach the MEA to make the Bucher Papers public.

Seventh, the scheme of the Public Records Act prohibits the transfer of classified government records to the NAI. So, if the Bucher Papers are classified “secret” or “confidential” how do they continue to remain in NMML’s custody when such classified papers cannot be held lawfully even by the NAI? Does this imply, that MEA’s fiat against the disclosure of the Bucher Papers is based on a mere policy decision of the government which has endured over more than five decades? If so, can it survive when tested against the stringent requirements of transparency under the RTI Act? This is the secondary purpose of my RTI interventions.

Eighth, the primary purpose of demanding access to the Bucher Papers is to ascertain facts contained in them to interrogate some of the theories and myths surrounding the government’s stance with regard to J&K. Growing up, many lads in our peer groups in school and college bought hook, line and sinker, various conspiracy theories about how Jawaharlal Nehru did not give the Indian Army the freedom to ‘liberate’ territories grabbed by the tribesmen invaders even though it had the upper hand, and how Lord Mountbatten or – according to some utterly vulgar claims – Lady Mountbatten influenced Nehru to refer the dispute to the United Nations (as if he was the dictator of the country who did not bother to consult his Cabinet before making this decision). Unfortunately, such fanciful literature is more easily accessible to the people than the documents-based output of scholars.

Everybody on the sub-continent has the right to know the truth and that too from the horse’s mouth. Sir Roy effectively held command of the armed forces for a major part of the Kashmir operations in 1947-48. He appears to have held a particular view of how things shaped up during that difficult period. If the transcript of interviews of soldiers who returned from the Kashmir operations is publicly accessible at NMML, thanks to the efforts made by Gen. Kodandera Subayya Thimmayya to record them (I have read them, but could not get copies as they are typed on sheets of paper thinner than an onion peel), there is no justifiable reason why the Bucher Papers should be under wraps. That is, unless such disclosure is likely to harm certain pet narratives bandied about as “the authentic version of the history of those times.”

Last but not the least, given the ever-growing popularity of alternative facts and the vigorous efforts to manufacture and disseminate revisionist, divisive and supremacist narratives of the past, it is all the more important to equip the citizenry with the actual facts and the tools required to make sense of them.

In my humble view, it would be wrong to say that we should leave the history research to historians who have the academic tools to do so. The phenomenon of ‘citizen journalism’ would not have emerged if news reporting were the sole preserve of journalism and mass communication graduates. When satellites are being designed and handed over to ISRO for launch by students and young graduates who are yet to cut their professional teeth in that institution or at NASA, and para legal volunteers are available in the thousands to help people who do not have easy access to professional lawyers, history research cannot remain restricted to the domain of an elite few. Knowledge production and dissemination were the monopoly of the upper castes and the elite classes across the globe for more than two and a half millennia. In the 21st century, we can avoid the folly of creating newer categories of privilege in this domain of human industry.

Venkatesh Nayak is Director, Commonwealth Human Rights, New Delhi. Views are personal.

The copyright for all papers exhibited in this write-up which were sourced from NMML, vests with the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library.

The copyright for all papers exhibited in this write-up which were sourced from NAI, vests with the National Archives of India.

This article went live on February twenty-first, two thousand twenty three, at thirty minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.