Patel Was Not the Sole Architect of the Integration of Princely States; Nehru Too Deserves Credit

As the country waves flags and celebrates the 75th anniversary of India’s independence, it is also time to take stock. What did India’s founders and citizens dream of, how has India fared, what have been our challenges and successes?

The Wire’s reporters and contributors bring stories of the period, of the traumas but also the hopes of Indians, as seen in personal accounts, in culture, in the economy and in the sciences. How did the modern state of India come about, what does the flag represent? How did literature and cinema tackle the trauma of Partition?

Follow our coverage to get a rounded view of India@75.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

"The thirsty traveller had been given a pot with no neck or bottom but with nine holes. But India’s master potter made it whole” – this is how Rajmohan Gandhi, one of India’s finest historians, describes Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s “work of unifying India” in his biography Patel: A Life (1991).

The tribute is well-deserved. In the year marking 'Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav', we must remember that it was the Iron Man of India who successfully integrated almost all the 560 princely states into the Indian Union. To realise the historic importance of this task, it is useful to turn to another page in Gandhi’s book, in which he quotes Winston Churchill, Britain’s haughty prime minister, as saying India should be divided ”into Pakistan, Hindustan and Princestan”.

With the partition of India and creation of Pakistan, the British empire achieved one of its objectives before exiting the largest of its 57 colonies. Had it succeeded in the second objective, India would have been balkanised into a large number of independent nations ruled by princes. But that was not to be. And the credit for preventing this denouement should go mainly – although not solely – to Patel.

As a result of partition, India had lost an area of 364,737 square miles and a population of 81.5 million. With the integration of princely states, an area of nearly 500,000 square miles (almost equal to that of the provinces directly ruled by the British) with a population of 86.5 million (not including Jammu and Kashmir) was added to the Republic.

As a civilisational entity, India has a history of over 5,000 years. But it never was a single and united political entity, ruled as it was by succession of kingdoms in different parts of its vast landmass. The closest that an empire came to achieving political homogeneity over a large part of ancient India was during the reign of Chandragupta (324-300 BC). But considering the very weak ways of communication prevailing at the time, it cannot be said that the Mauryan empire had established a uniform kind of political control or administration throughout its territory. Thus, India became an independent nation-state for the first time in its long history only after August 15, 1947.

Patel himself put it aptly: “The great ideal of geographical, political and economic unification of India, an ideal which for centuries remained a distant dream, and which appeared as remote and as difficult of attainment as ever, even after the advent of Indian independence, was consummated by the policy of integration.”

Also read: India@75: Why Does Deprivation Still Exist to This Extent?

A humungous task, (almost) peacefully accomplished

The most noteworthy aspect of the integration of states was how peacefully it was accomplished in most of them, the only exceptions being Jammu and Kashmir, Hyderabad, Junagadh and Manipur. This became possible principally because the people residing in these states desired to be part of independent India as strongly as those in British-ruled provinces. They identified themselves as Indians first, and not as subjects of princely rulers.

After all, in terms of social and economic relations, language, customs, etc., there was no difference whatsoever between the people in princely states and their counterparts in British-ruled provinces. In most places, the two mingled freely. This created a natural common bond between them. Strengthening this bond, and using it for the larger cause of India’s independence, was one of the greatest accomplishments of the freedom movement led by the Congress.

The All India States Peoples' Conference (AISPC) or Praja Mandals, a platform of popular movements against pro-British princely rulers, was an ally of the Congress in this nationalist mission. The link between the Congress and AISPC (established in 1927) was somewhat tenuous in the beginning. Mahatma Gandhi initially advocated a policy of non-interference in the affairs of princely states, more as tactics than as strategy.

However, as India’s freedom struggle grew in intensity, Congress leaders, especially Jawaharlal Nehru, began to espouse the cause of people’s supremacy over their rulers in princely states. Indeed, Nehru became the ‘permanent’ president of AISPC in 1939 and served in this position almost till India’s independence.

A photo of Jawaharlal Nehru with the Indian national flag. Photo: Unknown author/Wikimedia Commons, Public domain

Two other factors contributed to the peaceful integration of princely states. One, after the end of World War II, the British realised that they could not continue even their indirect rule in India through the ‘Paramountcy of the Crown’ over princely states. The Indian Independence Act of 1947 passed by the British Parliament recognised only the two dominions of India and Pakistan. The Act also stipulated that paramountcy would lapse with the creation of these two dominions, which meant that the princely states had to accede to either India or Pakistan. Mountbatten, the last Viceroy, made it clear that accession should follow the principle of geographical contiguity. As a result, all the princely states in the Indian dominion, barring Jammu and Kashmir, had no option but to accede to India.

Secondly, the Congress leadership also took care to mollify the princes by granting them ceremonial titles like ‘Rajpramukh’ and privy purses (which were abolished by Indira Gandhi in 1971). V.P. Menon, who served as secretary in the ministry of states and was Patel’s most trusted aide, writes in his monumental work Integration of the Indian States:

“The alternative to a peaceful and friendly settlement of the States’ problem was to allow political agitation to develop in the States and to create, especially in the smaller ones, dire confusion and turmoil. Anyone conversant with the conditions in the country after partition must be aware of the inherent dangers of such a course. The situation demanded stability and we had to take strong action against any agitation of which anti-social elements might take advantage. The only course therefore was to negotiate a friendly settlement with the rulers. If we expected them to hand over their States unconditionally and for ever, we had of course to give them something in return. It could not be ‘heads I win, tails you lose.’…By the time the Constitution came into force on 26 January 1950, we had integrated geographically all the States and brought them into the same constitutional relations with the Centre as the provinces.”

Speaking about the speedy yet smooth integration of princely states, Prime Minister Nehru said in September 1948: “Even I who have been rather intimately connected with the states' people’s movement for many years, if I had been asked six months ago what the course of developments would be in the next six months since then, I would have hesitated to say that such rapid changes would take place… The historian who looks back will no doubt consider this integration of the states into India as one of the dominant phases of India’s history.”

Also read: On Independence Day, Hyderabad Remained a Vast Hole at the Centre of New India’s Map

Police action in Hyderabad

One of the hardest problems Patel faced was the integration of the Hindu-majority princely state of Hyderabad, which was under a Muslim ruler. Since it was located in the heart of India, the Nizam could not have remained independent (which was his wish) or become a part of Pakistan (which was Jinnah’s wish).

Behind his unwillingness to accede to India was a fanatical and militant socio-religious force of 200,000 Razakars led by Kasim Razvi. They threatened the Indian government by saying, “The Nizam is willing to die a martyr and lakhs of Muslims are willing to be killed.”

In his preface to Menon’s book, veteran journalist M.V. Kamath writes: “According to VP, ‘Every time any action against Hyderabad was mooted, the communal bogey was put forward as an excuse for inaction.’ (But) the Razakars had gone berserk. It was only when it was clear that no alternative remained, did the Government of India take the decision to send Indian troops into Hyderabad on 13 September 1948. It was a swift operation that barely lasted 108 hours. The Hyderabad Army surrendered on the evening of 17 September. The number of dead was a little over eight hundred. VP said, ‘There was not a single communal incident in the whole length and breadth of India throughout the time of the operation…Had the Nizam acceded to India in August 1947, he would have won the affection of his subjects. It is axiomatic that no nation can afford to be generous at the cost of its integrity and India had no reason to be afraid of its shadow.’”

Junagadh, another Muslim-ruled Hindu-majority princely state on the coast of Gujarat, followed a different route to become a part of the Indian Union. The Nawab acceded to Pakistan despite his state’s non-contiguity with the newly created Muslim nation. Samaldas Gandhi, a respected Congress leader, formed a government-in-exile of the people of Junagadh.

Ultimately, Patel ordered forcible annexation of Junagadh. The Nawab fled to Karachi, where he established a provisional government! A plebiscite was held on February 20, 1948, in which 99.95% of the population voted to join India.

Manipur merged with the Indian Union on September 21, 1949 following the signing of the Instrument of Accession by Maharaja Bodhchandra Singh and V.P. Menon and Assam governor Sri Prakasha for the Government of India.

Jammu and Kashmir is the only erstwhile princely state that defied a solution. Even the nature of the problem has materially changed in the past seven decades since its genesis in the turmoil of India’s partition and because of the unending hostility between India and Pakistan. But that is a subject whose examination is beyond the scope of this article.

Also read: A Largely Unfair Assessment of Nehru Seen Through His Debates With the Other Leaders

Let’s not forget: Nehru was PM, not Patel

Finally, an enduring myth needs to be busted. True, Patel, as the minister of states (he was also the minister of home affairs) tasked with their integration into the Indian Union, deserves the main credit for accomplishing a herculean task. But a popular belief, deliberately bolstered in the past eight years after Narendra Modi became prime minister, has now acquired the status of an irrefutable historical fact – namely, that Patel is the sole architect of this mission. By erecting the world’s tallest Statue of Unity as a monument to him in Gujarat, Modi has personally endorsed this myth.

But history tells a different story. Patel was the deputy prime minister in a government headed by Prime Minister Nehru. It is foolish to think that any minister, even a deputy prime minister, can act independently in the Indian system of governance. Nehru kept himself abreast of all the important developments pertaining to the princely states. Furthermore, as we have seen earlier, Nehru was intimately associated with the issue since he was, after all, president of the AISPC.

In fact, in his presidential address at the AISPC session in 1946, he sternly warned the maharajas that those who refused to join India and India’s constituent assembly would be considered hostile states.

Finally, Nehru, along with Patel, wielded enormous influence in the constituent assembly, in which the princely states had a significant number of seats. All the pertinent points concerning the integration of princely states were discussed in the cabinet, which was headed by Nehru, as well as in the constituent assembly. Nehru also chaired the states' committee in the constituent assembly, which prepared the Constitution of the Indian Republic. Occasionally, differences arose between him and Patel, and they both turned to the Mahatma for guidance.

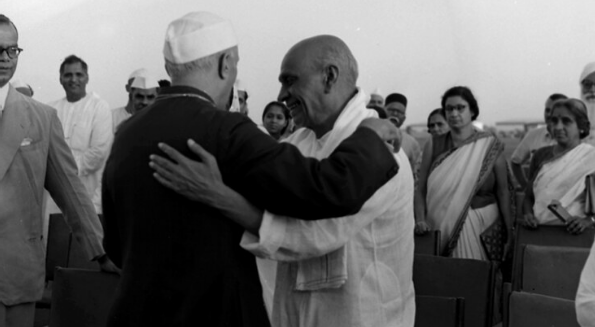

Jawaharlal Nehru with Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. Photo: Public Resources.org/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Patel’s role in the integration of princely states has been exaggerated by the Modi regime precisely because of its intent on maligning and erasing Nehru’s contribution in the freedom movement and in the making of modern India. However, a grateful nation that is truthful to its own history would hail both its great sons for accomplishing a mission of humungous magnitude that changed the destiny of India.

Sudheendra Kulkarni served as an aide to former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and is the founder of the ‘Forum for a New South Asia – Powered by India-Pakistan-China Cooperation’. He is the author of Music of the Spinning Wheel: Mahatma Gandhi’s Manifesto for the Internet Age. He tweets @SudheenKulkarni.

This article went live on August twenty-first, two thousand twenty two, at zero minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.