Subhas Chandra Bose, Meghnad Saha and the Birth of the National Planning Commission

Subhas Chandra Bose was shining bright on the Indian political firmament in the mid-1930s. His unflinching commitment to the anti-colonial struggle, in spite of years of imprisonment and exile, had raised his popularity all over the land.

He was even well-known abroad; his book The Indian Struggle had been a success, and he had been featured on the cover page of Time magazine. It was in this scenario that Bose delivered his (rather long) presidential address at the 51st annual session of the Congress at Haripura in February 1938. In it, he outlined the strategy for socioeconomic development that India would largely follow for the next several decades.

Bose started his speech with a detailed analysis of the workings of the British Empire.

He went on to elaborate the fundamental rights that citizens would enjoy in the future nation. He assured listeners that "the culture, language and script of the minorities and of the different linguistic areas shall be protected…All citizens are equal before the law, irrespective of religion, caste" and envisioned that "state shall observe neutrality in regard to all religions."

Next, Bose turned the focus on the blueprint for economic and industrial advancement.

In his typically confident tone, he declared, "I have no doubt in my mind that our chief national problems relating to the eradication of poverty, illiteracy and disease and to scientific production and distribution can be effectively tackled only along socialistic lines" and hence one of the first duties of the future national government "would be to set up a commission for drawing up a comprehensive plan of reconstruction."

Bose explained the importance of agricultural modernisation, abolition of Zamindari and land redistribution would not be enough and hence, "industrial development under state ownerships and state-control will be indispensable."

Thus, it would be the duty of the planning commission "to carefully consider and decide which of the home industries could be revived …and in which sphere large scale production should be encouraged."

In a poke at the Gandhian purists, he declared that "we cannot go back to the pre-industrial era" but then recognised the necessity to minimise the evils of big corporate-backed industrialisation and the importance of "reviving cottage industries where there is a possibility of their surviving the inevitable competition of factories."

All of this was not futuristic speculation. Congress cabinets were in power (however limited) in seven provinces following the electoral success in the 1937 provincial elections.

Now Bose reminded the Haripura delegates that, in October 1937, the seven labour ministers had already met to work out a uniform programme for "education, health, prohibition, prison reforms, irrigation, industry, land reform, workers’ welfare etc."

It was also in this context that the new president took a stand diametrically opposite to Gandhiji’s. He declared that there was no question about the Congress party withering away after the British left. "On the contrary, the Party will have to take over power, assume responsibility for administration and put through its programme of reconstruction. Only then will it fulfil its role."

Bose concluded the section by asking the soon-to-be-set-up Planning Commission to "work for comprehensive scheme for gradually socialising our entire agricultural and industrial system."

The first steps for policy-driven industrialisation had, of course, already been taken at the August 1937 session of the Congress Working Committee in Wardah. The CWC had empowered the provincial ministries to appoint an ‘interprovincial Committee of Experts’ for ‘national reconstruction and social planning.’ It was realised that ‘extensive surveys and the collection of data’ was essential and special mention was given to ‘comprehensive river surveys… for the development of hydro-electric and other schemes…[by] large-scale state planning’.

The words echoed the socialist spirit of Jawaharlal Nehru who, in his presidential address at Faizpur in December 1936, had stated that "only a great planned system for the whole land and dealing with all these various national activities, co-ordinating them, making each serve the larger whole and the interests of the mass of our people…can find a solution.…"

Jawaharlal Nehru speaks to a refugee. Photo: GOI, Public domain

However, not surprisingly, such words had alarmed the right-wing of the CWC and a significant section of businessmen and actual work had been slow.

Bose’s own thoughts had been crystallising on this well before Haripura.

In January 1938, in an interview with Rajani Palme Dutt for The Daily Worker, he had stated that he wanted India "to move in the direction of Socialism."

Also read: Remembering Nehru as a ‘Friend of Science’

A more elaborate view comes from his speech (titled Municipal Socialism) at the Bombay Corporation in May of that year.

Drawing upon the comprehensive work he had himself witnessed in Vienna, Bose urged his audience to understand that "today a modern municipality has to furnish not merely pure drinking water, roads, lighting, etc., but it has to provide primary education and it has to look after the health of the population …[including] infant mortality, maternity" and even banking.

And, once in office, president Bose took it upon himself to speed up things.

In May 1938, he chaired a special CWC session of the seven chief ministers where setting up of industries and sharing of power resources was the focus. A couple of months later, in July, he asked for an early conference with Ministers of Industry to assess the existing industrial scenario "as preliminary to the appointment of the Expert Committee to explore possibilities of an All-India Industrial Plan."

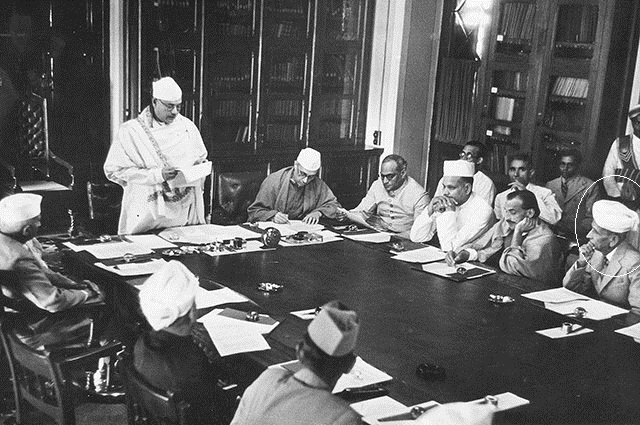

Subhas Chandra Bose addresses the first meeting of the National Planning Committee in 1938, Bombay. Others present include Chairman Nehru, Patel, Kripalani, Meghnad Saha, M. Visveswaraiah. Photo: Twitter/@Advaidism

It must be noted that while three decades of neo-liberalism may make many frown at such ideas today, in the 1930s, socialism-based state industrialisation was the most acceptable model to many Indian thinkers.

Not only the formal leftists, but Rabindranath Tagore’s Letters from Russia and Jawaharlal Nehru’s Soviet Russia are replete with admiration for what they felt would redress 150 years of unbridled capitalist-imperialist loot of the land. Various aspects of planned industrialisation were being discussed.

In August 1938, the prestigious ‘Modern Review’ carried a special issue covering a wide range of articles on industrial planning – with Acharya Prafulla Chandra Roy, professors S.S. Bhatnagar and V. Subrahmanyan, and A.R. Dalal among the authors. The legendary Sir M. Visveswariah and the economist N.S. Subba Rao had written books on the subject.

At the session of the Indian Science Congress, the president, Jnan Chandra Ghosh (the future director of IISc, Bangalore) elaborated on the necessity to bridge the basic sciences and industries. As Nehru summed it up in a letter to young Indira, "Everybody talks of planning now…The Soviets have put magic into the word."

But, one man was perhaps the most strongly motivated of them all – physicist Meghnad Saha.

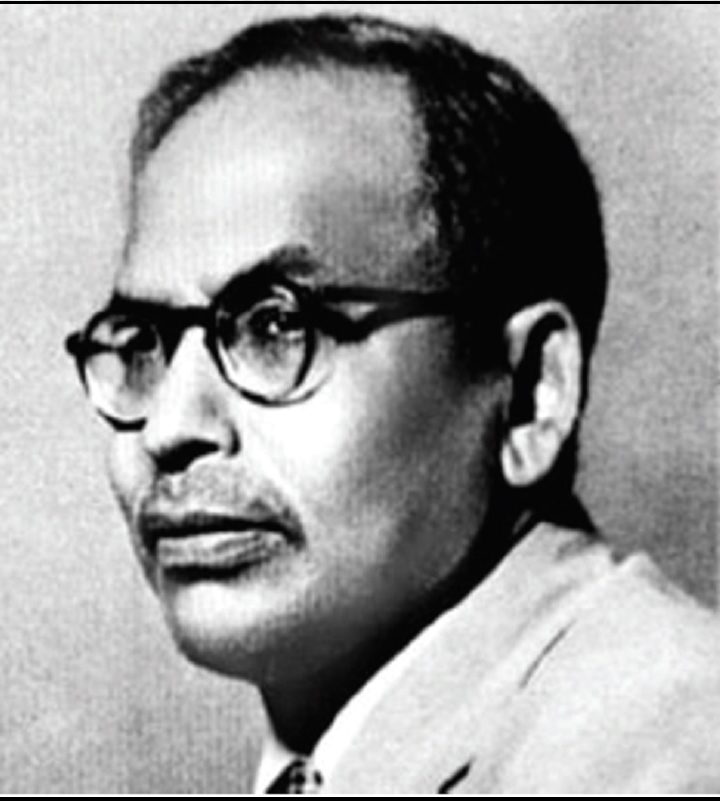

Meghnad Saha. Photo: Public domain

A nationalist, who had dabbled with anti-colonial struggle during his studenthood, Saha’s rise – from the humble (and often humiliated) 'low' caste origins in rural Bengal to one of the stars of the international astrophysics fraternity – remains inspiring to this day. And, it is probably for this upbringing that he had absolutely no ‘soft nostalgia’ for serfdom-based rural life.

Hence, not content with his bright scientific career, Saha started the journal Science and Culture which became a steady source of research updates and scientific temperament, and counted Bose among its admirers.

A strong advocate of ‘large scale industrialisation’, Saha’s August 1938 essay 'The Philosophy of Industrialisation' hit hard at what he perceived to be the futility of ‘Gandhian’ cottage industries and bluntly stated that many Congress leaders "themselves have no clear-cut philosophy of action for national reconstruction" evoking a counter from Gandhian cottage industries advocate, J.C. Kumarappa.

It was at this stage that Saha invited Bose to the annual session Indian Science News Association. Here, at the questionnaire session, Saha wanted ‘Rashtrapati’ Bose to tell the audience if India was "going to revive the philosophy of village life, of the bullock-cart – thereby perpetuating servitude" or was there going to be "modern industrialised nation" to redress "the problems of poverty, ignorance and defence?"

Also read: Infinite in All Directions: Nobel's Women, Meghnad's Caste, Tantalum's Decay

If the latter was the answer, would Congress "establish a National Research Council and mobilise the scientific intelligentsia of the country," Saha asked.

Bose tackled the broadside with frankness. He conceded there were differences within the Congress on this matter, but then assured the audience that, within the party, "the rising generation are in favour of industrialisation."

Bose went on to elaborate that since India was "still in the pre-industrial stage," the industrial revolution was inevitable. The critical question was, according to him, whether "industrialisation, will be a comparatively gradual one, as in Great Britain, or a forced march as in Soviet Russia. I am afraid that it has to be a forced march in this country."

His thoughts about national reconstruction and autonomy involved "growth and development of the mother industries, viz., power supply, metal production, machine and tools manufacture, manufacture of essential chemical, transport and communication industries."

To achieve this, "technical education and technical research" (free from stifling bureaucratic control) would have to be updated with a "clear and definite plan" to send students abroad so that they can return and set up and join new industries. The big need of the hour was a "permanent National Research Council."

And all this demanded a strong multi-tiered collaboration between politicians and scientists.

Bose stressed that "national reconstruction will be possible only with the aid of science and our scientists" and concluded with words that would resonate to this day:

"We, who are practical politicians, need your help, who are scientists, in the shape of ideas. We can, in our turn, help to propagate these ideas and when the citadel of power is finally captured, can help to translate these ideas into reality. What is wanted is far reaching co-operation between science and politics."

The conference of Ministers of Industry was organised at Delhi in early October 1938. The ministers were present as were J.B. Kripalani (Congress secretary), G.D. Birla, Sir M.V. and Meghnad Saha. In his welcome address, Bose pointed towards the paradox that "unemployment may become worse as a result of scientific agriculture" but hoped that since "India is a country with resources similar to those of the United States of America," planned exploitation of the superabundant natural wealth would serve the people.

He cited his favourite example, that of Soviet Russia which had been "no better than India…but within the last 16 years she has passed from a community of primarily half-starved peasants to one of the primarily well-fed and well-clothed industrial workers."

He emphasised that the Soviet example "deserves our careful study and attention, irrespective of the political theories on which this State is based…"

An image of V.V. Giri on a stamp of India. Photo: GODL-India

The conference concluded with the decision to appoint a Planning Committee. It would submit its initial report within 4 months to the CWC and then get enlarged to a more inclusive All India National Planning Commission. V.V. Giri (the future president of India) was entrusted with the setting up of the commission. Immediate emphasis was placed on the ‘national importance that industrial and power alcohol should be manufactured in India and the necessary raw material, chiefly molasses’ procured from the ministries of Uttar Pradesh, Madras, Bombay and Bihar.

Of course, Bose knew he would need help. And who better than the only one in the CWC who shared his socialist dreams – Nehru.

For most of 1938, Nehru had been abroad, canvassing for the Indian cause. Bose’s letter of October 19 found him in Spain. The warm tone reveals this was the high noon of their political (and also personal) bonding.

"You cannot imagine how I have missed you all these months…I hope you will accept the Chairmanship of the Planning Committee. You must if it is to be success."

Nehru accepted without hesitation because, he felt, "It is a good thing to begin thinking on right lines and make others do so" and "because I am intensely interested in planning."

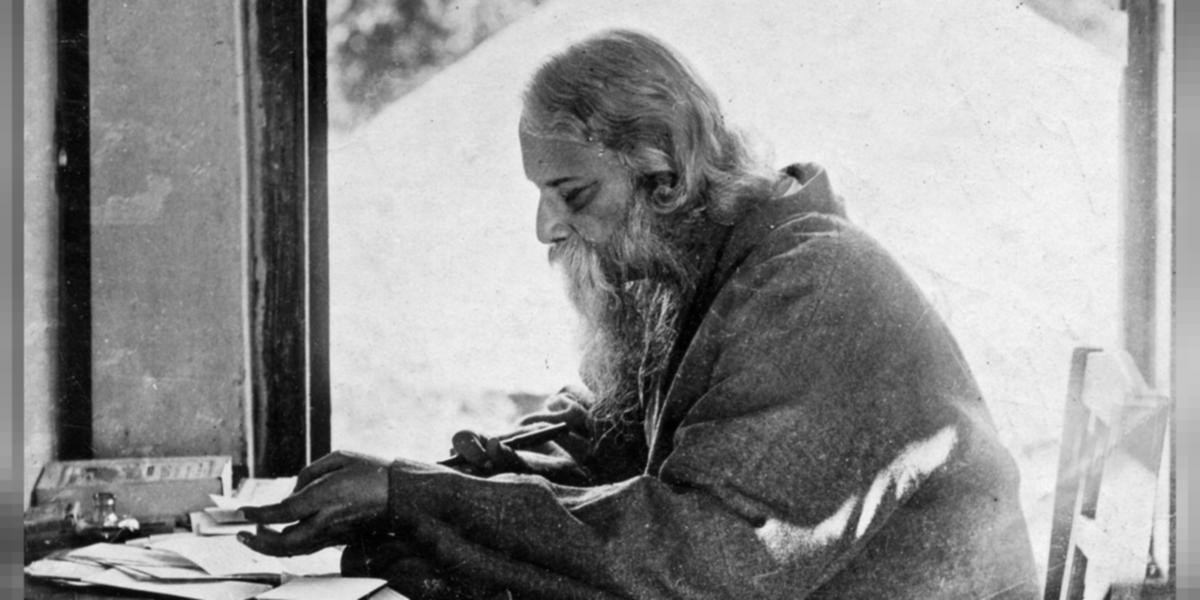

Saha must have felt assured with the proceedings, but, he realised it would be better if Bose continued to be at the helm. To bolster support, he approached ‘the sun’ of India’s cultural world, Rabindranath Tagore. In sharp contrast to what one would expect from a ‘poet of nature’, Tagore’s love for scientific advancement was neither new nor casual. He had been a promoter of formal technical education, since the early Swadeshi and Khadi days. Hyper-enthusiastic Swadeshi enterprises which often ended in ridiculous failure, and ‘the cult of the charka’ were not his forte. The great scientist Sir J.C. Bose had been his lifelong friend. He considered Nehru and Bose as the only ‘two genuine modernists’ among the national leadership.

Rabindranath Tagore at work in his study at Santiniketan. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

So Saha travelled to Shantiniketan and using numerical data explained how industrialized harnessing of natural resources had increased per capita productivity in the West while India lagged behind.

Tagore was impressed "by the forceful way Saha called for shunning all useless ancient tradition." He agreed, "There is no spiritual solace in suffering and disease…and without scientific education and industrialisation, our heritage, whatever its greatness, was bound to get reduced to dust."

Under Saha’s persuasion, Tagore wrote to Nehru, "I have had a long and interesting discussion with Dr Meghnad Saha… as you have consented to act as the President of the Committee formed by Subhas for the guidance of the Congress, I would like to know your views on the matter." He also expressed his interest to Bose.

When the All India National Planning Committee met in Bombay on December 17, 1938, under Nehru’s lead, it counted 15 experts. Besides Sir M.V. and Saha, it included scientists like Nazir Ahmad and J.C. Ghosh, economists K.T. Shah (who served as Secretary) and Radha Kamal Mukherjee. The businessman lobby – also prime Congress financiers – was well represented by Sir Purshottamdas Thakurdas, A.D. Shroff, Walchand Hirachand and Ambalal Sarabhai. Trade union leader N.M. Joshi and cottage-industry advocate J.C. Kumarappa were there as well, as were V.V. Giri and the ministers. It did seem representative of the multitiered complexities (and contradictions?) that had become integral to the anti-colonial struggle by now.

As Nehru noted crisply, "Some good people like Saha…others not so promising."

Gandhiji was present even in his absence. Well aware that not much would be achieved without his support, both Bose and Nehru spent a substantial fraction of their speeches assuaging that ‘planning’ would not hamper the cottage industry.

Bose went on to simulate how "if in the city of Benares, we could supply electrically driven looms along with electrical power at the rate of half-anna per unit, it would be possible for the artisans working in their own homes to twin out sarees and embroidered cloth of different varieties at about five or six times the present rate of production …and rescue them from the depths of misery and poverty…"

Chairman Nehru made similar assurances about the cottage industries and then stressed that "the planning committee keeps itself in touch with the national movement." It would have to have "a certain reality –intellectual, objective and psychological," or it ran the risk of becoming a "tame affair…lost itself in the backwaters and simply discuss isolated and individual bits of industrialisation…."

Gandhi remained largely unconvinced as later correspondence shows, but the business lobby, with close ties to him and Sardar Patel, was satisfied.

Thus, a pivotal enterprise had been launched – one that would steer India’s decisions for decades to come. Significantly, the Committee prepared an exhaustive and detailed questionnaire and sent it to collect material data, and obtain helpful suggestions…from provincial governments, Indian states, organisations of trades, industries, commerce, labour and agricultural interests, firms and corporations, as well as to individuals "who have devoted thought and study to the general question of an all-round national planning for the economic regeneration of the country."

A detailed analysis of the questionnaire and the subsequent proceedings demands more than an article by itself. But its sheer breadth – 167 questions in the primary list and another 70 in the supplementary, with several sub-enquiries – is overwhelming to this day and gives a good insight into the concerns of the men who had taken it upon themselves to build a modern post-colonial nation. Six months later, in June 1939, the answer sheets had been received (sometimes with prodding) and twenty-seven subcommittees had been appointed for in-depth analysis.

The ‘very commendable initiative’ earned the praise of even the London-based Financial Times. It was heavy-duty work and, as Nehru wrote to Bose in June 1939, "The work….which you entrusted to me last year grows bigger and bigger and takes up a great deal of time and energy. It is exhausting business."

At the political arena, as is well known, Bose had now set ‘sail in a different boat’ that would soon lead him to an adventure like no other. In a twist of political meandering, the man who had envisioned a left-inclined socialist future for his people found himself allying with ultra right-wing oppressive regimes of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

Also read: These ‘Foreign Hands’ Left Their Homes to Fight For India’s Freedom

But planning for India remained a core conviction and his articles and speeches, while at Berlin and Tokyo, show he was certain that "the Committee has already done valuable work and its reports will be helpful for our previous activity." The Committee continued its work till September 1940.

And although Bose was not around when independent India embarked on the five-year plans in the 1950s, it is obvious that the work of the Planning Committee he co-founded had been the pathfinder. Decades later, on the golden jubilee of India’s independence, the Planning Commission, then chaired by Madhu Dandavate, honoured Bose’s efforts with a compilation of his speeches and letters on the subject and appropriately titled it ‘Pioneer of Indian Planning’.

Indeed, along with the National Anthem, it is Bose’s longest-lasting legacy to the republic and it is quite unfortunate that his pioneering efforts in nation-building have been obscured by a "perpetual death mystery."

But it is high time to change focus. To quote from the Tom Cruise-starrer The Last Samurai:

'Tell me how he died’

‘I’d rather tell you how he lived.’

Anirban Mitra is a molecular biologist and a teacher residing in Kolkata.

This article went live on January twenty-sixth, two thousand twenty three, at fifteen minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.