Sunil Kumar – Historian and Mentor Gone Too Soon

It was meant to be a celebration of decades of teaching, scholarship and mentorship. It was supposed to be a chance for the large community of scholars influenced, cajoled and challenged by Sunil Kumar to reminisce, laugh and most importantly, to learn. Even as it became apparent that the gathering would have to be online, the retirement party would still be a great opportunity to get Sunil’s many students, colleagues and friends together, and celebrate the person whose kindness, generosity and intellect had touched many lives in small and big ways. Sunil e-mailed me on January 7 to confirm that “sometime around May would be a lovely time for this event”.

And with that particular cruelty that has characterised so much of the past year, ten days later, on January 17, Sunil Kumar, professor of history at Delhi University, my teacher, mentor, friend, passed away. The gaping hole I feel is not just a reflection of a sudden tragedy that none of us expected. It is from the many ways my relationship with him evolved over the years from a graduate student to colleague, a relationship marked by his incredible generosity and kindness, whether it was reading drafts of my book or talking with me at all hours about the struggles of being a young academic.

I first met Sunil as a graduate student in the old campus of Arts Faculty in Delhi University in the fall of 2000. Sunil’s reputation as a demanding professor was fairly well-established in the circles of budding historians, a reputation that was only bolstered by his imposing height and very deep husky voice. Understandably, several of my peers and I were “scared” to be in his class as he carried into the classroom his shoulder bag full of manila folders with photocopies of excerpts from Barani’s 14th-century chronicle and recent articles from journals not accessible to us anywhere in the university library. As we pored over Juzjani’s chronicle and Nizam al-Din Awliya’s discourses, we were also introduced to the work of Orlando Patterson, Michael Chamberlain, Jonathan Berkey and Carl Petry, among others. I still have bound photocopies of several of these monographs that were impossible to find in bookstores back then.

Also read: Sunil Kumar Changed How Historians Think About Islamic Rule in Medieval India

We read deeply and widely, and Sunil brought a great degree of dynamism and energy into the classroom at the time when most other instructors of ‘Medieval India’ carried on instructing in their very uncharismatic and dull ways, how the historiography on the Mughals had developed between Nationalist and Marxist frameworks. I was hooked and my real training as a historian began in earnest. Over the course of the next five years, Sunil provided the intellectual scaffolding necessary for reading primary sources with rigour and creativity, and for writing that valued independent thinking. We later often joked about the folder Sunil maintained on his computer with numerous drafts of my MPhil chapters in it; Sunil was indeed a demanding professor, but one who brought out the best in you.

Sunil’s love and passion for teaching history was matched by exacting standards for his own scholarship and his boldness in asking new questions to historical materials. Two of his articles from before his first book on the Delhi Sultanate came out – “Assertions of Authority” (in Muzaffar Alam et al, eds, The Making of Indo-Persian Culture, 2000) and “Qutb and Modern Memory” (in Suvir Kaul, ed, The Partitions of Memory, 2001) provided compelling, nuanced readings of sultanate textual narratives and architectural remains that challenged the simplistic use of the categories of “Hindu” and “Muslim” that had informed the interpretative framework of much of the scholarship on the medieval period.

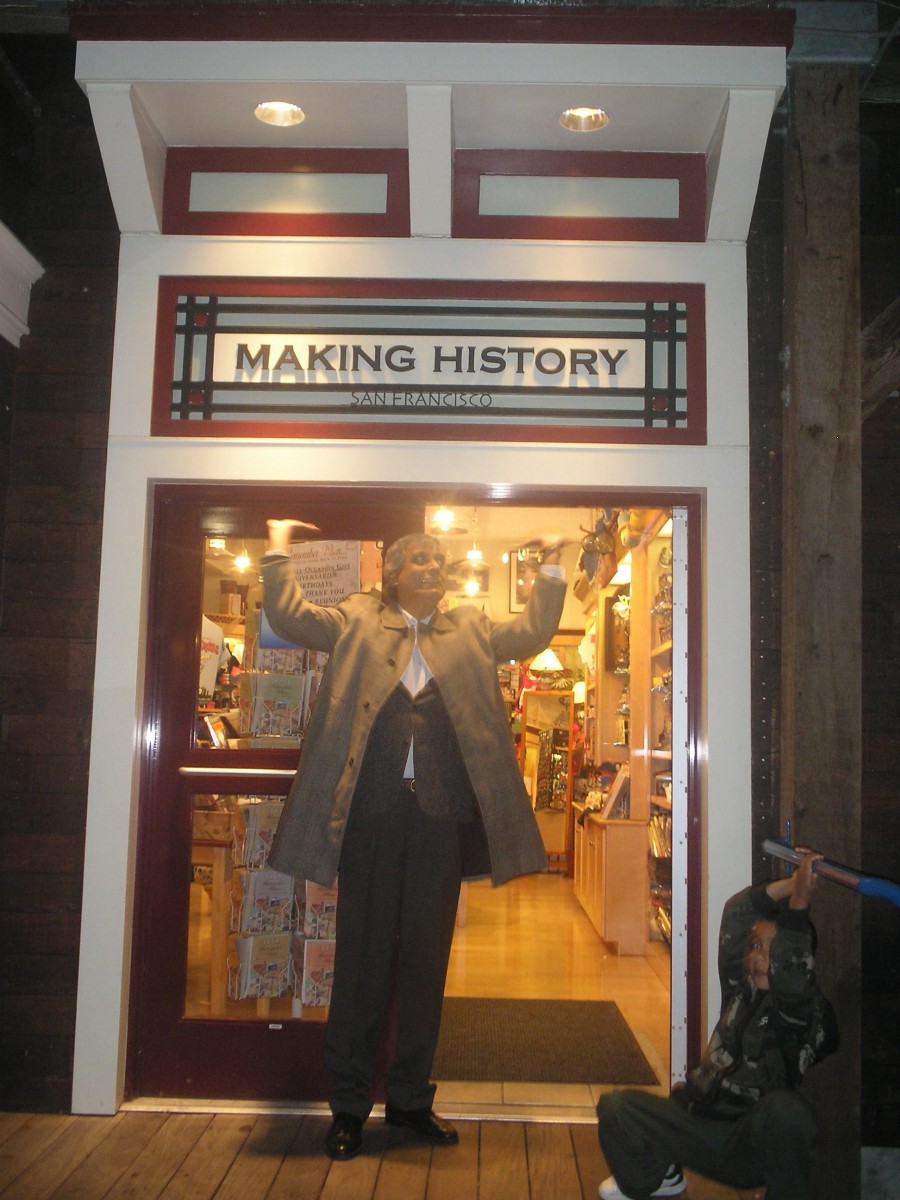

Sunil Kumar in San Francisco in 2008, when he was a resident fellow at Townsend Center at UC-Berkeley. Photo: Author provided

His meticulous readings of Persian texts produced in Delhi courts and in the context of Sufi residences in the 13th and 14th centuries demonstrated that it was possible to recover change to understand shifting patterns of power, piety and service in the Delhi Sultanate. As I converted the old computer files of his PhD dissertation on the Delhi Sultanate into Word files sometime in 2004, I saw firsthand Sunil’s commitment to drafting and redrafting until he was (nearly) convinced that it was time to bring the book out into the world.

I didn’t learn from Sunil in the classroom only. Many of our lively discussions took place in the Arts Faculty canteen over deep-fried samosas and sugar-loaded chai, especially during crisp Delhi winter mornings. It was in part thanks to these regular informal conversations that by the middle of our MPhil programme, we were no longer “scared” of Sunil, we admired him, made jokes with him, and thrived in the joint commitment to be the best historians that we could possibly be. Sunil also took great joy in taking his students on fieldtrips to Mehrauli and Tughlaqabad; after all, we were surrounded by structures of the sultanate period in Delhi and what better way of bringing the past to life than wander in the ruins of thirteenth century Delhi?

Indeed, visiting many sites of Delhi became a regular feature each time I visited him in Delhi after moving to the US in 2005. Always generous with his time and excited to share his knowledge, he gave me and my partner an extensive tour of the Qutb complex and the nearby Mehrauli village in 2009, though we came very close to driving into a ditch. I was also lucky to visit with him a few of the sites that had been the focus of his essays in The Present in Delhi’s Past in which he not only retold the past of several forgotten historical sites, but also chronicled the ways in which the present was reshaping nearby communities’ memories of that past.

As my mind rushes through the last 20 years of bonding with Sunil as a student and a friend, my memory of him would be incomplete without mentioning something more personal. I grew up in a grittier, middle-/lower-middle-class part of Delhi that is far from the places and areas that most tourists would visit. I did not grow up hanging out in Khan Market or attending events at the India International Centre. Indeed, often due to lack of support, the horizons for many in my extended family, especially the women, consisted largely of finding suitable partners and raising a family. My parents didn’t fit this mould and were always supportive, but they had little knowledge of educational institutions or the academic world to provide more than emotional support. Indeed, living at home with protective parents, Sunil fielded more than one frantic call from my mother if I didn’t return at the exact hour that I said I would!

Needless to say, without Sunil’s generous support, due in large part to the two years that I worked as the editorial assistant at IESHR, the journal for which he served as the Managing Editor, I never would have developed professionally and may well have found myself, like so many neighbours and cousins, living a life of unrealised potential. Instead, Sunil urged me to go abroad to further develop my skills. Unlike many Indian families, we had no such rubric or history of family members doing graduate work of any type, let alone graduate work in the United States. And when the time came, Sunil sat down next to me to review graduate programmes at Chicago, Michigan, NYU and UCLA, and taught me how to reach out to prospective advisors. He told me it was time to start a new journey, a new adventure, and find my wings. Thus, in no small or ancillary way, I owe my career to Sunil Kumar.

Even when I left India in 2005 and found my wings (and several other remarkable mentors along the way), Sunil always remained readily available whenever I needed to vent, seek advice and catch up in general. Receiving his emails lit up my face, hearing his voice on the phone reminded me of how far our relationship had come since 2000, and seeing him in person brought me immense joy. I’ll miss those conversations, those jokes, that deep interest in my career and insight to provide guidance in my work. There will be other scholars of medieval India and the Delhi Sultanate, but only one Sunil Kumar.

Jyoti Gulati Balachandran is assistant professor of history at Pennsylvania State University. Her research focuses on social and cultural histories of Muslim communities in Gujarat and the western Indian Ocean.

This article went live on January nineteenth, two thousand twenty one, at thirty minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.