The Blame – and the Shame – of Three Million Bengali Dead

The Bengal countryside is "the biggest archive in the world", comments a contributor to a new BBC audio series, 'Three Million'. The wartime famine which claimed so many Bengali lives happened in plain sight. True, that was 80 years ago, and almost all eyewitnesses and survivors are now dead; but there are still, in all likelihood, thousands living with indelible memories of that trauma.

Yet there is no monument or memorial anywhere to all those who wasted away. The story has faded just as those subsisting on rice water slowly shrank to nothing.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

The bald geo-strategic facts are well established. As the Japanese army advanced deep into Burma in 1942, the war cabinet in London worried that Bengal too might fall to the enemy. The British authorities introduced a policy of ‘denial’ – destroying stocks of grain and the small boats so essential to Bengal’s economy lest they fall into Japanese hands.

There was no absolute food shortage – yet three million, some say more, starved to death. From the viceroy’s residence, Lord Wavell stormed about what he described as "one of the greatest disasters that had befallen any people under British rule" with "incalculable" damage to Britain’s reputation. But London wasn’t listening. And there were no spare ships to bring in emergency food supplies.

Winston Churchill, Britain’s wartime prime minister, is often held to blame for the Bengal famine. This five-programme series doesn’t seek to convict him. But it does include telling testimony that in wartime he regarded the Empire as subordinate to the British homeland, and that he saw Indians as a sub-species.

Alongside the blame, there’s the shame. The British government must bear culpability. But it wasn’t Brits who hoarded the grain, took land from starving peasants in exchange for a small sack of rice, and bought young girls for a pittance for sex.

Class is another reason why the famine has been brushed away out of sight of the main historical narrative. If you were rich, you survived – there was food available if you could afford it. As ever, the poor and the marginalised bore the brunt – men often migrating to Calcutta and other towns in a desperate quest for work they were no longer strong enough to perform.

Kavita Puri. Photo: Special arrangement

The astonishing success of 'Three Million' is to present the famine as living history rather than a distant episode. It’s presented by Kavita Puri, one of the best documentary makers around. "The lived experience of the famine has not been well documented or remembered," Puri told The Wire, "and I wanted to recover these human stories." She does so with a sensitivity and compassion which never slips into shroud-waving sentimentality.

Puri talks to the Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, then nine years old and living in Shanti Niketan and appalled by the emaciated people who passed by. "How much can I give them?" he asked his grandmother. The answer: just half a cigarette tin of grain a day. That memory shaped his life. Much of his academic career has been devoted to what causes famines and how they can be avoided.

Pamela Dowley-Wise, born in Calcutta in 1926, saw "dead people all over", their carcasses preyed on by vultures. When the famine was at its most severe, as many as a thousand bodies a day were collected from Calcutta’s streets. The art historian, Partha Mitter, said that while his household had rice on the table every day, women would come to the gates pleading for a little of the water in which the rice was cooked.

Amid the tumult of war, the British authorities wanted to deflect attention from what they coyly described as the India food question. Ian Stephens, as editor of the Statesman in Calcutta, found a way around the wartime censorship. It applied to text not images. He sent his photographers onto the streets and on August 22, 1943, he published harrowing images of famine victims at the point of death.

Yet the Statesman never named the starving men and women whose photographs it published. They were emblematic of humanity but denied their individual humanity.

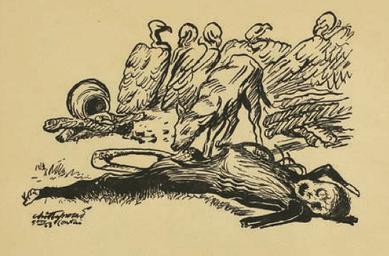

When Chittaprosad Bhattacharya’s intensely powerful drawings of the starving were published as Hungry Bengal – a book promptly impounded by the colonial authorities – he was sure to give his subjects the dignity of a name. A drawing of a corpse in Midnapore being worried by a dog is captioned: "His name was Kshetramohan Naik".

Chittaprosad Bhattacharya’s 'His name was Kshetramohan Naik'.

The BBC came under pressure at the time to downplay the gravity of the crisis. Puri uncovers evidence that it did indeed self-censor in its coverage of the famine. It’s taken an awfully long time, but these programmes at last make reparation for the BBC’s wartime failings.

The extraordinary achievement of this series is in recovering the voices of some of the non-privileged. In Cambridge, Puri came across long forgotten recordings of veteran Indian civil servants made in the 1980s. And we hear from a school teacher in his 70s, Sailen Sarkar, who has made it his mission to record the stories of village Bengalis who survived the famine.

The series would be stronger with more raw testimony of those who suffered hunger pangs. Puri planned to accompany Sarkar on one of his journeys – but her visa application was never approved. She is still hoping to make it to West Bengal and meet survivors.

There was one positive consequence of the famine. Its impact persuaded the first generation of post-independence politicians to strive to ensure that famine would never again stalk their nation. Broadly, that goal has been met: there has been no major famine in India since independence.

'Three Million' is available as a podcast from February 23 and will be broadcast on BBC World Service radio from March 2.

Andrew Whitehead is a former BBC India correspondent.

London Calling: How does India look from afar? Looming world power or dysfunctional democracy? And what’s happening in Britain, and the West, that India needs to know about and perhaps learn from? This fortnightly column helps forge the connections so essential in our globalising world.

This article went live on February twenty-sixth, two thousand twenty four, at fifty-six minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.