The Indian Legion of the German Armed Forces: Between Political Calculation and Nazi Propaganda

It is not very widely known that during the Second World War, the Wehrmacht (the German Armed Forces) also incorporated a number of non-European units, including Arab formations and an Indian legion. The latter was officially called the Indian Infantry Legion 950 and unofficially known as the “Tiger Legion” because the soldiers of this legion wore, in addition to the Wehrmacht uniform, a specially-designed badge on the right arm, depicting a leaping tiger.

The Indian legion comprised volunteers from the Indian Prisoners of War (POWs) who had fought the German and Italian forces in Africa as a part of the British Imperial Army. The Indian POWs were brought over to Germany from Africa in 1941 and given the choice to remain prisoners or to join the Wehrmacht as an Indian legion. Most POWs preferred to remain prisoners due to a number of reasons which we will discuss a little later.

The recruitment and training of the Indian POWs who opted to join the Germans commenced from 1941. By the beginning of 1943, the legion came to comprise around 3,500 soldiers. In May 1943, they were deployed near the North Sea coast in Holland. However, the cold and rainy weather there appeared to dampen the spirits of the soldiers.

Moreover, the German Army Staff began to suspect that the Indian Legionnaires were becoming much too friendly with the locals. Similar “troubles” had occurred in the training camps in Germany, where the “exotic” Indian men allegedly exerted magnetic powers of attraction over the local German women. The resulting interracial relationships threatened to disrupt the “racial purity” of the Volksgemeinschaft, or national community, as envisioned by the Nazi regime.

Therefore, in September 1943, the legion was transferred to the south of France, where it was given the task of patrolling a section of the Atlantic Wall – a stretch of the coastline extending about 60 kilometres west of Bordeaux. The Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944 forced the legion to retreat towards Germany. During this retreat, it became involved in violent battles with the maquisards, the French resistance fighters.

By December 1944, the legion was stationed in Heuberg in southern Germany, where it remained till its official disbandment in May 1945 by the American Army. The Indian soldiers were turned over to the British and subsequently sent back to India.

This well-known trajectory needs to be placed within its proper political context. In 1941, the Nazi regime began toying with the idea of forming an Indian Legion from the ranks of the Indian POWs who had fought in the British Imperial Army against the Germans in Africa. The idea of an Indian Legion was directed by political rather than military considerations.

Also read: Why the Second World War Remains Relevant for India Today

Hitler considered Indians to be an inferior race that deserved to be ruled by the British. However, after Joachim von Ribbentrop became foreign minister in 1938 and war with the British Empire appeared increasingly likely, German propaganda aimed at India began to strategically encourage the Indian anti-colonial movement with the goal of making things difficult for the British. The notion of raising an Indian armed unit of the Wehrmacht from the Indian POWs was an extension of this propaganda strategy.

Efforts to form an Indian Legion received impetus after Subhas Chandra Bose arrived in Berlin as a political refugee in April 1941. Bose sought Nazi Germany’s support to free India militarily. Hence, he suggested to Ribbentrop that an Indian army should be formed from the ranks of the Indian POWs who had been captured in Africa. This suggestion corresponded well with existing German plans. Raising an army from these Indian POWs was a joint venture of the German Foreign Ministry, the Wehrmacht, and the Free India Centre (FIC), which Bose was allowed to set up in Berlin with local Indian civilians.

In order to identify the Indian Legion with Bose’s anti-colonialist agenda, the Indian soldiers wore on their armbands the symbol of a leaping tiger, which had been chosen by Bose for the FIC.

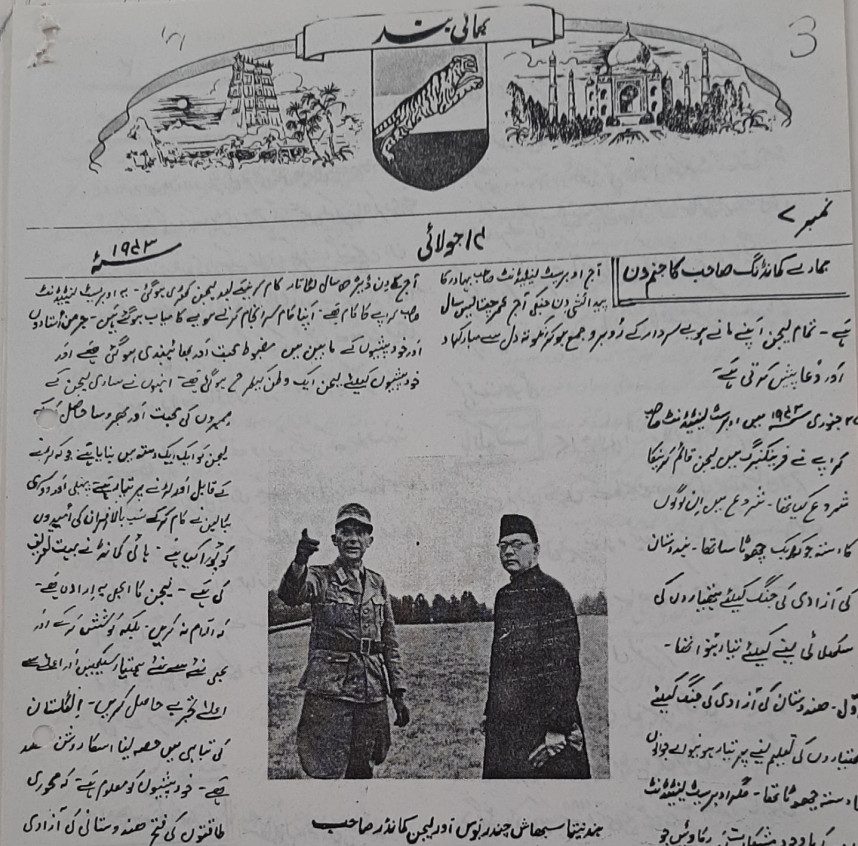

An issue of the Indian Legion's magazine, Bhaiband, showing the commander of the Legion, Kurt Krappe (left) with Subhas Chandra Bose. Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv: MSG/230/32.

However, despite fervent appeals to Indian nationalism by Bose and a few of his Indian associates from the FIC, only a small number of the POWs could be persuaded to join the legion. This was because most Indian POWs who were brought over to Germany from Africa were ordinary soldiers fighting under the British colonial masters for reasons of livelihood. For these men from humble backgrounds, the idea of fighting for an ideal, in this case freedom from colonial rule, was too abstract.

Also, following its strategy to appear friendly to Indians, the Nazi regime was lenient in its treatment of the Indian prisoners as compared to prisoners from other countries, like the Soviet Union for example.

As in the case of other foreign military units, the Wehrmacht intended to exercise full control over the Indian Legion. The way to achieve this was through political propaganda glorifying the achievements of Nazi Germany and its ‘Führer’ as well as by indoctrinating the soldiers in the Nazi world view. The command of the legion was given to Major Kurt Krappe, a pro-Nazi military officer. The reason for his appointment, according to a post-war British report, was that he had lived in Tanganyika, Africa, for a long time and had experience in dealing with ‘colonials.’

The colonial aspect was not a coincidence. Colonialist thinking, carrying the imprint of the British imperialist outlook that characterised the Indian soldiers as savages in need of civilising, was prevalent among the German military personnel, along with the biological racism popularised by the Nazis. Racial prejudices led the Germans to refer to the Indians as ‘Bimbos’ and the legion’s predominant language, Hindustani, as ‘Bimbostani’ when talking amongst themselves.

This racist approach was also reflected in a handout written for the German officers by Ulrich von Kritter, one of the adjutants of the legion. This pamphlet claimed that Indians were primitive in certain respects, which made them susceptible to pedagogical influence. For Kritter, the ideal medium for influencing them was the legion’s magazine Bhaiband (translated into German as Kamerad or comrade).

This magazine was published at frequent but irregular intervals from mid-1943 to the beginning of 1945. It remains one of the most tangible manifestations of the German attitude towards the Indian soldiers, who remain largely voiceless. Bhaiband was written by hand in Urdu and Hindi and printed at a press in Bordeaux. Though it claimed to be written by Indian soldiers, Bhaiband was actually composed by a number of German scholars specialising on India and/or the Islamic “Orient”, who acted as interpreters in the Indian Legion.

Mediation between the Wehrmacht and the Indian soldiers required specialised knowledge of Indian languages and customs since the legion comprised soldiers from different regional, linguistic, and religious backgrounds. Such knowledge could be provided only by academic experts on India. Interpretation was a politicised function in Nazi Germany. The regime expected the interpreters to be “politically reliable” agents who would, along with translating languages, propagate the greatness of the Reich among foreigners.

Ernst Bannerth, the chief interpreter of the legion and the other scholar-interpreters who edited Bhaiband – Eugen Rose, Paul Thieme, and Karl Hoffmann – were well equipped to answer this political demand.

An examination of Bhaiband points to its role as a weapon of Nazi propaganda. It disseminated the Führer cult among the Indian soldiers by eulogising Hitler in the guise of informing them about German history. The authority of the German ‘Führer’ was also invoked time and again, for example, to make the recalcitrant Indian soldiers accept the Indian Legion’s incorporation into the Waffen-SS. Anti-Bolshevism, another predominant component of Nazi worldview, was propagated in various ways, including a regular, vituperative column called “What is Bolshevism?” The pamphlet was also used to reinforce the authority of the legion’s commander Kurt Krappe, often by alluding to Bose, who had left for East Asia in February 1943.

Also read: Seeing Kashmir in Sicily: How Indian Soldiers Felt During the Second World War

One such write-up claimed that it was Krappe who decided to start the legion. The text went on to mention the “deep friendship” that purportedly existed between Krappe and Bose, and concluded with the cry of “long live Hitler” and “long live Netaji.” This dual salutation reflected the oath of allegiance that the Indian soldiers took to carry out Bose or Netaji's fight for the freedom of India by accepting Adolf Hitler, the supreme leader of the German state, as their Commander in Chief.

In November 1943, Bhaiband published a missive, supposedly from Bose, stating that he now officially placed the Indian National Army in Europe, i.e. the Indian Legion under German command. This message formally sanctioned the Wehrmacht’s complete control over the legion.

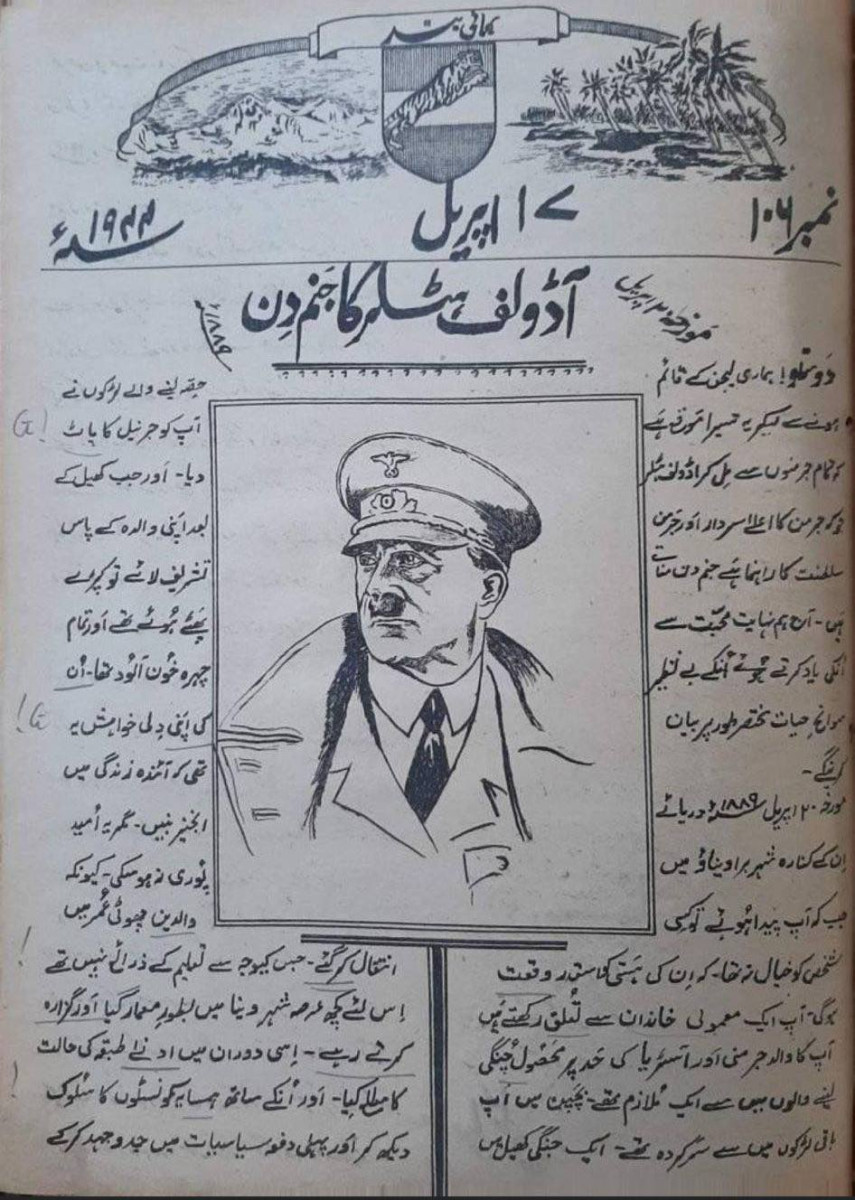

Hitler's birthday was celebrated by the Indian Legion, according to the issue of Bhaiband published on April 17, 1944. Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv: RS17/47.

Apart from Hitler, Bhaiband repeatedly mentioned the German Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, whose name was familiar to most Indian soldiers from their time in Africa. Rommel had “inspected” the Indian Legion after the Allied landing in Normandy in 1944. At that time, the Wehrmacht’s propaganda team had photographed Rommel with the Indian soldiers near the Atlantic Wall in order to reassure the domestic population that they were being protected.

Rommel’s name was subsequently cited in Bhaiband to reconcile the Indians to their inclusion in the Waffen-SS and to proclaim that the necessary task of the legion, now in retreat from France to Germany, was to vanquish the French resistance fighters.

Castigating the maquisards as “Communo-terrorists” was a part of the training provided by the Wehrmacht to its interpreters. Presumably, the interpreters of the Indian Legion were familiar with the idea of criminalising the French resistance. According to Eugen Rose, one of the interpreters who wrote an auto-fictional account of his time with the legion after the war, the violent skirmishes between the Indian Legion and the maquisards were characterised by intense hatred on the part of Indian soldiers towards the ‘maquis’. However, the extent of the brutality displayed by the legion during its retreat remains controversial.

Bhaiband also deployed knowledge of India’s history and culture to inspire loyalty and fighting spirit. This was the distinctive contribution of the “India experts.” Popular patriotic songs and poems in Indian languages were quoted and there were frequent references to Indian anti-colonialist leaders, including Gandhi and Bose, to motivate the soldiers to fight a war that actually had little to do with India’s independence. The diverse traditions pertaining to the three religious communities represented in the legion – Sikhism, Hinduism, and Islam – were also called upon to address certain alleged problems that resulted from Bose’s stipulations.

Also read: From Reims to Karlshorst: On the Trail of History’s Greatest Military Capitulation

In the British Imperial Army, every Indian regiment consisted of battalions formed on the basis of religion, region, or ethnicity. The language of command was English. Following his political vision, Bose insisted that Hindustani should be the language of command. Every unit of the Indian Legion was to incorporate men from diverse religious, linguistic and regional backgrounds. A pan-Indian identity was to replace sectarian ones.

Ernst Bannerth, the chief interpreter, and Eugen Rose later claimed that Bose’s vision of a non-segregated Indian Legion resulted in the marginalisation of religion and “moral depravity” of the soldiers. “Depraved acts” included the consumption of alcohol even by Muslims and visits to the brothels – activities that were regularly engaged in by the German soldiers. Both Bannerth and Rose clearly expected the Indians to remain what they considered to be true “Orientals”. For them, a non-religious Oriental was not an authentic Oriental.

The Indian Legion, which was conceived primarily as a tool of Nazi propaganda, was thus subjected to different forms of racism that intersected the Nazi worldview, colonialist attitudes, and Orientalist scholarship.

A version of this article was published in the magazine of the German Historical Museum, Historical Judgement, in October 2025.

Baijayanti Roy is a lecturer and researcher affiliated to the Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main. Her book, 'The Nazi Study of India and Indian Anti-Colonialism' was published in 2024 by Oxford University Press.

This article went live on November twelfth, two thousand twenty five, at twenty-two minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.