Traversing the City: The First Urdu Guidebook of Mumbai

The contours of Mumbai have been redefined innumerable times over the last few centuries. From the hypothetical seven islands which made up the city, Mumbai has physically merged with many of the islands – Salsette, Trombay, Chembur – which surrounded it and now make up metropolitan Mumbai. Perhaps the most ambitious remodelling project in the history of the city was initiated in the 1860s with the demolition of the walls of the Fort. Both the coastlines of the v-shaped city changed beyond recognition.

On the eastern foreshore, the old basins and docks gave way to two massive reclamation projects: the Moody Bay Reclamation which extended from the Mint to the erstwhile Carnac Bunder and the even more ambitious Elphinstone Reclamation which extended another mile and a half northward to Mazagaon. The Bombay port, the nerve centre of the city, was fashioned anew to allow larger ships to anchor at its docks. A new railway line, an extension of the Bombay, Baroda and Central India Railway (now the Western Railway), snaked its way along the western side of the island city before terminating at the newly constructed wharf near Apollo Bunder.

Maclean’s Guide to Bombay. Photo: Author provided

After the fort walls were pulled down, a whole new town – Frere Town –was laid out on the old Esplanade with a network of arterial roads. A series of monumental edifices – the Elphinstone College, the Watson Hotel, the high court, the University buildings and the Secretariat – were erected in the 1870s in Frere Town. Though the name soon fell into disuse, the Frere Town layout and buildings continue to define downtown Mumbai.

By 1875, a visitor coming to the city after 15 years would have been hard-pressed to anchor himself. It was the perfect time to publish a guidebook to the city. In November 1875, the Bombay Gazette Press published Maclean’s Guide to Bombay. In the following month, Munshi Naval Kishore of Lucknow published a guidebook to the city of Mumbai from his eponymous press. Titled Tilism-e Bambai, the book was written in Urdu by a Parsi who had recently moved from Mumbai to Lucknow. It was the first Urdu book on the city and one of the earliest guides to the metropolis in any language. What was a Parsi doing in Lucknow? And how did he write a book on Mumbai in Urdu?

Parsis in Lucknow

The first Parsis to travel across north India in significant numbers were camp followers with the regiments of the East India Company in the 1830s and ’40s. They would have traded in goods imported from Europe. Their clientele would mostly have been European soldiers and civilians. And perhaps a nawab or two. By the 1850s, Parsis had set up shops in cities like Delhi, Allahabad and Kanpur. Besides European goods, they were famous for their stock of liquor, wine and beer.

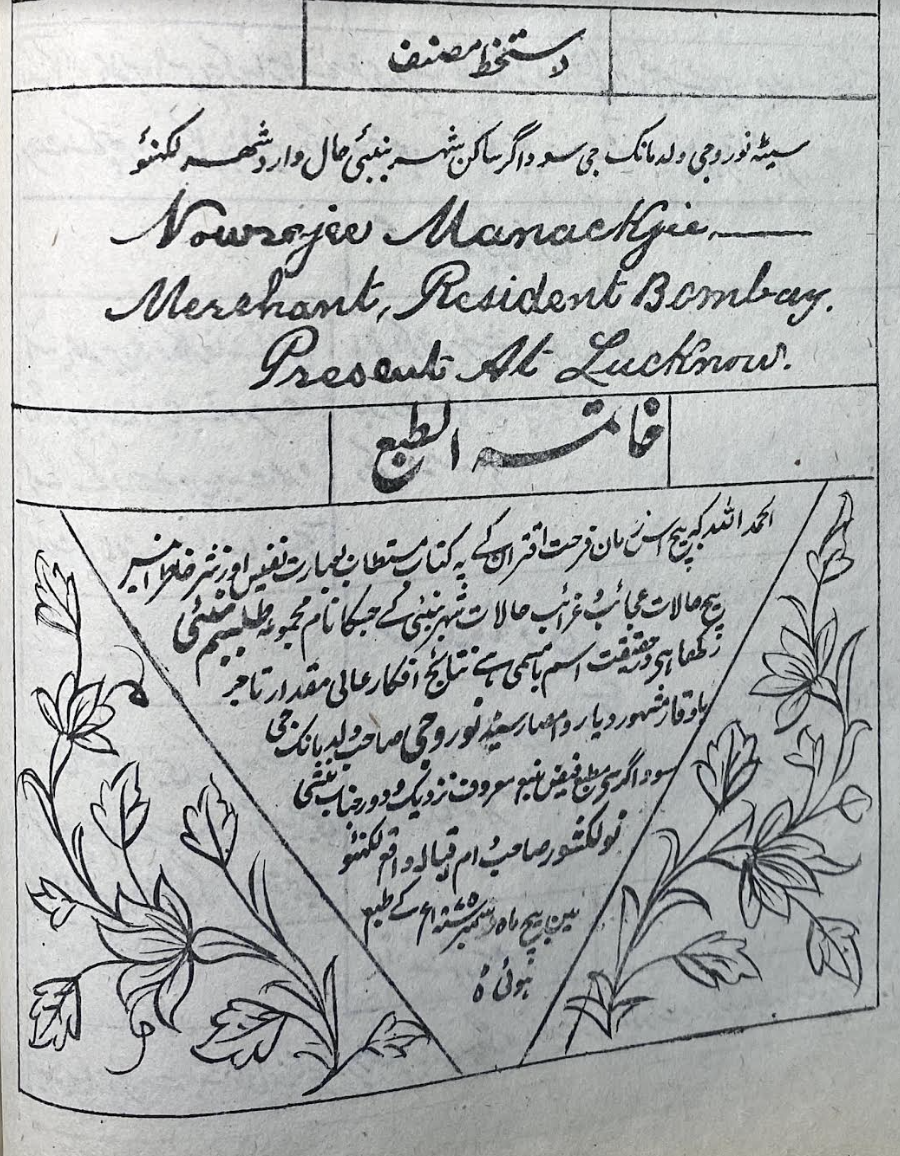

Tilism-e Bambai, English and Urdu colophons. Photo: Author Provided

Though the number of Parsis resident in the Gangetic plains gradually increased after the 1857-59 war of independence, the Parsi presence in north India was sparse and scattered for most of the nineteenth century. A Parsi resident in Lucknow would have had to travel a thousand kilometres in any direction to visit a fire-temple. He could either go west to Lahore or east to Calcutta; if he travelled south towards Mumbai, he would encounter a fire-temple in Mhow in central India.

Lucknow, as it transited from being the capital of the nawabs of Awadh to a colonial city, was an attractive location for Parsis hoping to make their fortune. By the early 1870s, the number of Parsis resident in Lucknow was close to 100, including a few families. The Lucknow Parsi Anjuman maintained an aramgah, a burial ground for Parsis. In 1872, a community hall named Harmuzd Bagh, still standing, was constructed opposite the aramgah with funds from Framji Shapurji Coachbuilder.

It was around this time that Nowrojee Manackjee, the author of Tilism-e Bambai, came to Lucknow. As a person whose presence in the public sphere is a mere blip, scant information is available on him. Could he be the Nowrojee Manackjee Contractor who is listed by the Parsee Prakash as having matriculated from the University of Bombay in 1868? It is possible that after his matriculation he travelled to Lucknow to try his luck in business.

Munshi Naval Kishore and his Press

Founded in 1859 by Munshi Naval Kishore (1836-95), the Naval Kishore Press soon acquired a reputation as one of the most prominent publishers and printers in north India. By the mid-1870s, its catalogue included an extensive list of books in Hindi, Urdu, Arabic and Persian. The world of books was gradually changing in this period. Printers were commissioning books on their own account and taking on the role of the publisher. Additionally, the education departments of the colonial government were issuing print orders for textbooks with large print runs.

Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy Hospital. Photo: Author provided

Munshi Naval Kishore was well positioned to benefit from this printing boom and was one of the first Urdu printers to evolve into a publisher. Most of the early imprints from the Naval Kishore Press were textbooks, like the Urdu Jam-e jahan numa, a geography textbook by Munshi Shivaprasad (1859) or the Hindi Patvariyon ke hisab ki pustak by Ramsharandas (1860). It soon expanded into poetry which had an assured market in those days; for example, Lalluji Lal’s Premsagar or the Gitavali of Tulsidas. Munshi Naval Kishore also published the works of Urdu poets, living or dead: Ghalib, Mir, Zafar and Momin. Persian classics and their Urdu translations were another mainstay of the press. Exquisitely lithographed editions of the Quran, first issued by the Naval Kishore Press in 1868, found thousands of buyers.

Munshi Naval Kishore constantly tried to expand the market for books and print. He retained a team of translators who could translate from English, Sanskrit and Persian to Urdu and Hindi. He acquired the copyright of texts from their authors or their descendants. And he was exploring new genres of publications. Travelogues had been published in Urdu from the 1840s but it was still not a genre with commercial possibilities. Yatra literature has a fairly long history in Hindi and Naval Kishore published a few Hindi pilgrimage manuals: Kanhaiyalal’s Banyatra (1868) and Gursharan Lal’s Avadhyatra (1869). But even for him, a guidebook to a city was a foray into unknown territory.

How did Munshi Naval Kishore conceive the idea of a Mumbai guidebook? And who was he hoping to sell it to? While a few Parsis were moving to north India to amass fortunes at a scale no longer possible in Mumbai, a large number of north Indians were travelling in the opposite direction. The city was experiencing an unprecedented boom and its economy could support anyone who chose to try their luck. With the coming of the railways, the traffic between the city and stations upcountry increased dramatically. Businessmen, students, tourists and pilgrims began to visit the city in large numbers. Mumbai also emerged as the port of embarkation for north Indians performing the Hajj. Every year, thousands of Muslims would camp in the city as they acquired their travel passes and tickets and awaited embarkation on ships bound for Arabia.

Naval Kishore, a keen observer of trends and opportunities, must have felt that there was a ready market for a guidebook to Mumbai. While scouting for a suitable writer, he may have encountered a young and educated Parsi, recently arrived from Mumbai, who seemed to have a good knowledge of the city, its history and its hotspots.

The enchanted city of Mumbai

Tilism-e Bambai is a 16-page lithographed book. It is divided into two sections: the first eight pages include the title page and a long prologue describing the history of the city, its principal inhabitants and their charities. The last eight pages are a guide to Bombay and its monuments. The calligraphy of the text is competent and the print quality is good.

As a resident of Bombay, Nowrojee would have been conversant with the Bombay version of Urdu: Bambaiyya. From the numerous spelling mistakes in the text, especially of Parsi names, it is obvious that Nowrojee could not read Urdu. He would have needed an amanuensis who was proficient in Urdu to render his account of Mumbai on paper. The title of the book perhaps holds a clue as to the person with whom Nowrojee collaborated.

An Arabic word sharing Greek roots with the English word ‘talisman’, ‘tilism’ had acquired a wide range of meanings in Urdu: spectacle, magic, mystery, enchantment. The Naval Kishore Press had already published two books whose titles started with ‘tilism’. While Tilism-e Shayan, a translation of a Persian dastan, was published earlier in 1862, Tilism-e Hind, a 500-page history of Awadh, was published in 1874. Both these books were authored by Totaram ‘Shayan’ Lakhnavi, an Urdu poet and one of the translators associated with the Naval Kishore Press. It is very likely that Munshi Naval Kishore assigned Totaram to work with Nowrojee to produce the Urdu text.

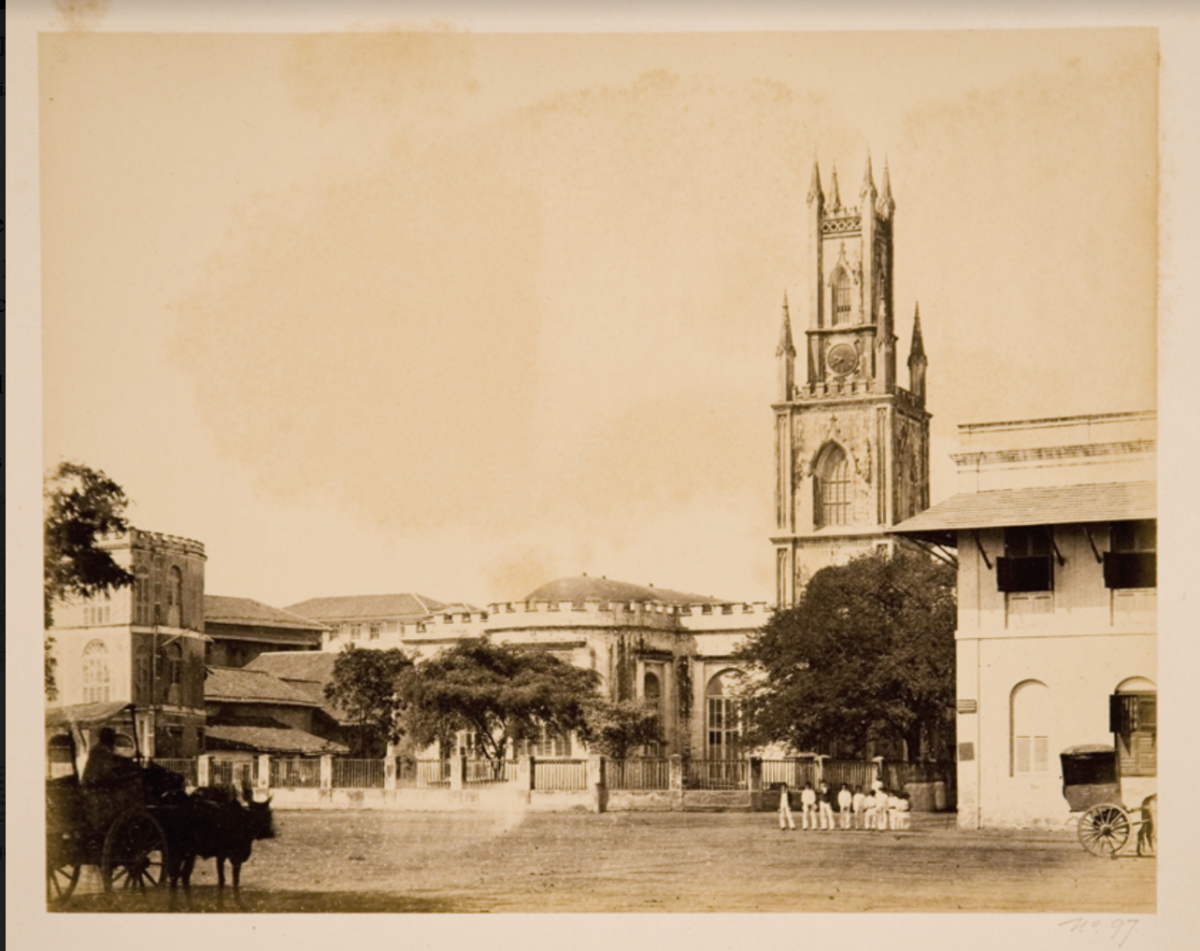

The English Cathedral in the Fort. Photo: Author provided

Nowrojee's vision of Mumbai was limited by his own experiences which were largely within the Parsi community. And the Parsis dominate the narrative, both in the prologue and in the guide. He waxes eloquent about Parsi institutional charities like the Parsee Punchayet and the Association for Ameliorating the Condition of the Zoroastrian Population of Persia. The charitable acts of munificent Parsi sethias such as Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy and his hospital in Byculla are also described.

The guide to Mumbai, barely eight pages long, is set in three columns. Nowrojee describes each neighbourhood in turn and lists the main buildings and sights. Starting with Colaba in south Mumbai, he moves northward to Palava Ghat (Apollo Bunder), Maidan (Esplanade), and Kot (Fort). He then moves on to old ‘native town’ with its Market, Mama Devi ka Mohalla (Mumbadevi), Kalkadevi and Panjarapol. Veering westward, he encounters Dhobi Talao, Chowpatty and Girgaum. He doubles back on Grant Road to Tardeo encountering Karel Wadi and Khetwadi. He then moves on to the suburbs: Byculla, Mahim, Parel, Mahalaxmi, and Walkeshwar. He does not miss out on locales in the eastern port district: Tank Bunder, Mazgaon and Mandvi.

In each neighbourhood, he lists the important buildings and describes them in short phrases. If it has been funded by a Parsi, he does not neglect to mention the fact. The longest entry, crammed into four columns, is devoted to the Fort neighbourhood, the area enclosed by the fort walls before they were demolished.

Most of the descriptions are formulaic – good, grand, magnificent – as the following extract shows.

§

Mohalla Kot [Fort]

The Government Mint where rupees and paisa are manufactured using machines; the Angrez Bazaar where English and Indian traders have their shops, what a wonderful and interesting place, worth a visit; Mulla Feroze Madrassa, what a good edifice; the hospital for whites, this building is also magnificent; the Parsi Jamaatkhana, the community hall associated with the name of Manekji Sett, a beautiful structure indeed.

The fortress which houses the armoury, worth a visit; the English church, it is a very well-built and magnificent structure; the Parsi Girls’ Madrassa, very good; the Parsi hospital built with charitable funds, a good building.

The Town Hall where elite members of the public hold meetings, also has a library and images of the prominent businessmen of Mumbai; the Pahlavi and Zend Madrassa built by Sir Jamsetjee Jejeeebhoy, what a grand building; the Government Secondary School, a very good building; the residence of Sir Jamsetjee Jejeeebhoy, what a good building.

Frere Town, its buildings and gardens are worth a visit; the Madrassa where only Parsi boys and girls are taught English and Gujarati, this building built by Sir Jamsetjee Jejeeebhoy is also very well designed; the Dongri fortress, a magnificent building; the gymnasium, also a good building.

The guidebook contains one of the earliest mentions of Dadar. “Dadra: this neighbourhood has many gardens which are worth visiting; the settlement is located on a hillock, indeed a captivating place. The station for the railway from Baroda and Surat is well constructed.”

A reader of Tilism-e Bambai would form the impression that Mumbai was a Parsi city. Every neighbourhood from Mahim in the north to Colaba in the extreme south seemed to have structures built by Parsis: causeways, fire temples, schools and colleges, hospitals, community halls, sanatoriums, gymkhanas, textile mills and private residences. While roaming the localities of Mumbai, it is Parsi public buildings, such as Merwanjee Framjee Pandey Sanatorium at Colaba or the Cama Baug in Khetwadi, which catch his eye. It could be the Mahim Causeway built with funds provided by Lady Avabai, wife of Sir Jamsetjee or the Maneckjee Petit Spinning and Weaving Mills in Tardeo.

Nowrojee does not completely overlook the existence of other communities and religions in Mumbai. He mentions a few temples and a synagogue. However, he struggles to recall the names of mosques and only mentions Zakaria Masjid at the very end of the narrative, perhaps prompted by his interlocutor. He completely overlooks the dargahs of Mumbai, perhaps the most popular resort of Mumbai citizens of all religious persuasions. Nowrojee however does not lose sight of prominent citizens from other communities. Though he is unable to provide any details, he does list a few names such as Jugonnath Sunkersett, Nakhuda Mohammad Ameen Roghay and Sir David Sassoon.

In contrast to the modest aspirations of Tilism-e Bambai, the English guidebook published in the same year, Maclean’s Guide to Bombay, claimed to be the definitive guide to the city. Extending to over three hundred pages, it covered the historical and statistical aspects of the city and described its various locales in great detail. Authored by James Maclean, the editor and proprietor of the Bombay Gazette, it became so popular that the Gazette Press issued it as an annual volume, A Guide to Bombay, for the next twenty-five years. Each successive edition was updated to reflect the rapid changes in the city’s skyline. The final edition of the book appeared in 1902 by when the text and format had become hopelessly outdated.

Does Nowrojee Manackjee survive in the archival records? Tilism-e Bambai seems to have been his only literary venture. In the 1890s, Nowrojee Manackjee & Co was listed in trade directories as a wine and general merchant based in Faizabad, about hundred kilometres from Lucknow. Could this wine merchant be the same person who wrote the Mumbai guidebook twenty years earlier? Perhaps.

Tilism-e Bambai seems to have been an experiment which did not succeed for its publisher. If one considers that Nowrojee was relying solely on his memory, had no previous literary experience and was perhaps illiterate in Urdu, his effort to evoke the spirit of Mumbai is creditable. Perhaps the book did not cater to the needs of its primary audience, Muslims en route to Hajj who wanted to visit the mosques and dargahs of Mumbai. No further editions of the book seem to have been published. Whether copies of Tilism-e Bambai reached Mumbai is unknown; perhaps a few visitors did use it to navigate the neighbourhoods and sights of the city. Not unlike other 19th century books on Mumbai published in local languages such as Marathi, Gujarati, Urdu and Persian, Tilism-e Bambai disappeared from the public arena soon after publication.

Murali Ranganathan is a writer and historian researching the 19th century with a special focus on print history and culture. The author wishes to thank Danish Khan for drawing his attention to this book.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.