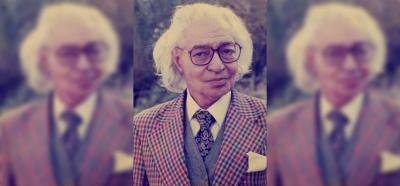

Eminent historian Vishwa Nath Datta, professor emeritus, Kurukshetra University and formerly general president of the Indian History Congress, passed away at his New Delhi residence on Monday. Born in 1926, Datta had an illustrious career as an outstanding academic and public intellectual, and belonged to independent India’s first group of historians who brought a secular, universal, scientific, literary outlook to the writing of modern Indian history.

Contemporary historians would swear by his steadfast commitment to the discipline of history until his death. He was not swayed by any ideological posturing through his career, and his rare composite and eclectic perspective provided a humane and rational reading of colonial and contemporary India.

During his lifetime, Datta took up multiple academic roles as visiting professor at a number of universities including Moscow, Leningrad and Berlin, and resident fellow of Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, and authored several pioneering works on different aspects of colonial history of India.

Born into an illustrious family of Amritsar as the son of the leading businessman [who owned the Shankar Das Vishwa Nath Company] and renowned Urdu-Persian poet Padma Shri Brahm Nath Datta ‘Qasir’, Datta lived through the trauma of Partition. However, that experience did not embitter his cosmopolitan outlook despite the fact that he had to cut short his studies at the Government College, Lahore, and move to Lucknow University, where he became a favourite of the renowned sociologist D.P. Mukherji.

In fact, all his life Datta remained a staunch advocate of a secular, progressive and inclusive India.

“His secularism, though, was of a different kind. It was shaped by his visceral experience of Partition and his sensitivity to realise that literature provides a human perspective on life and personalities. He was, besides, a true cosmopolitan whose nationalism had nothing narrow about it. At home equally with Ghalib and Shakespeare, he enjoyed his single malt. His cosmopolitanism was also reflected in his enduring friendships with Harivansh Rai Bachchan, Mohammad Mujeeb and Krishna Menon. Bachchan even dedicated one volume of his ‘Autobiography’ to Datta and his wife, Kamala,” says his daughter and senior historian Nonica Datta.

After his time in Lucknow University, Datta went to Cambridge University, United Kingdom for doctoral studies.

Among his well-known works are Jallianwala Bagh, which was the first work on the massacre of 1919; Amritsar: Past and Present; Sati: A Historical, Social, and Philosophical Enquiry Into the Hindu Rite of Widow-Burning; Maulana Azad, Gandhi and Bhagat Singh; New Light on Punjab Disturbances (2 volumes), and a biography of the revolutionary, Madan Lal Dhingra and the Revolutionary Movement.

Also read: V.N. Datta on Why the Context of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre Is So Important

He also edited the rare correspondence between senior Congress leader during the nationalist struggle and one of the founding members of Jamia Millia Islamia University Dr Syed Mahmud and Jawaharlal Nehru’s partner Kamala Nehru.

His latest work was the monumental history of The Tribune newspaper titled The Tribune: 130 Years: A Witness to History, published in 2011 and released by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in New Delhi. His book on Kurukshetra also presents a remarkable model of social history of a pilgrimage centre in that it is untainted by ideological posturing.

Datta’s discovery of Vols. VI and VII of the Disorders Inquiry Committee (also known as the Hunter Committee, appointed on October 14, 1919) was a great revelation as these volumes had been suppressed by the British government. That evidence provided crucial insights into the study of the events leading up to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. These volumes were released by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and were widely appreciated across the world.

Despite this stellar record, Datta was known as one of the most-affable and humble academicians by his peers and students.

Recalling his interactions with Datta recently, historian Anirban Bandyopadhyay wrote on his Facebook page,

“… Twelve or thirteen years ago, I used to work with a senior historian (Datta), as his research assistant. He was writing the centenary history of a major Indian newspaper. He was a legendary scholar and I a lowly M.Phil student. I worked with him for nearly a year. We would meet once a week. He would feed me excellent tea and sandwiches at an elite central Delhi address and ask me what I did during the week. He would nod and ask questions, advising me to look into some questions more rigorously than others and telling me countless stories of India when he had been younger and of various other places and peoples. There was absolutely nothing we could not discuss, including complicated personal questions.”

“He lit many lights inside me during that year. I may or may not get to meet him ever again, or have another conversation. There is no one to whom I am more grateful. He taught me how to recognise people with honour, without appearing either unctuous or condescending. He is one of the scholars I will always idolise,” he said about Datta.

Tanika Sarkar, senior historian who retired as professor of modern history at Jawaharlal Nehru University, remembered him as “so gentlemanly, civilised, fair, and so kind to all”.

“He was always prepared to admit if he had made any mistake even to scholars much younger than himself,” she said, adding that she learnt a great deal from his work on sati. She recollected how Datta gifted a book to one of her PhD students. “As an examiner of his PhD thesis, he thought it was a book the student should read,” she said.

“His work on sati is enormous in its course, covering its entire history. It is meticulously detailed backed by sharp analysis. It’s a very rare combination to see a work of that range which is so detailed, so lucid. I don’t think we sufficiently recognise the importance of that work. No one other than him has actually delineated how Sati was practiced across ages, and in different ages and by different communities. It’s the most comprehensive history of sati.”

She said that Datta had great enthusiasm for history, its research, and the archives. “Integrity of research was his primary concern,” Sarkar said.

Datta’s latest work, which is yet to be published, is on the life of Sarala Devi Chaudhurani. A member of the famed Tagore family, Chaudhurani founded the first women’s organisation Bharat Shree Mahamandal in 1910 to promote female education, and helped edit at least two prominent nationalist magazines in colonial India.

With Datta’s demise, an era of independent India’s first generation of distinguished and cosmopolitan historians, who were committed to a vibrant, and expansive idea of India has ended.

Datta is survived by his wife and three daughters. And by his large extended family of devoted students for whom he was a father-figure and a friend.