How V.P. Menon Viewed the Future of Jammu and Kashmir: A Vignette From October 1947

Earlier this month, Delhi Lieutenant Governor V.K. Saxena green-signalled the Delhi police's move to prosecute Arundhati Roy and professor Sheikh Showkat Hussain for speaking their minds about the state of affairs in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) at a public event 13 years ago. The former is a Booker Prize-winning author and public intellectual who does not hesitate to call a spade, be it matters relating to society, polity, economy or the survival of the entire planet. She preferred to spend a full day in prison rather than tender an apology to the Supreme Court of India for expressing views that the court deemed contemptuous of its majesty. The latter is a noted academic who trained generations of students in law and human rights but was unceremoniously removed as the principal of Kashmir Law College last year for views he publicly expressed about J&K.

Both will stand trial for the alleged offences of promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, and residence, and for allegedly making imputations, and assertions prejudicial to national integration. Two other co-accused have passed away during the pendency of these proceedings. However, the charge of ‘sedition’ that was hurled at all of them by the complainant – a J&K-based activist – will not be tried due to a Supreme Court-imposed stay on all proceedings relating to that offence.

Media reports indicate that the complainant approached the Delhi police because he found their speech provocative and supportive of the aspirations for ‘freedom’ that were being aired at that time by some individuals and groups in relation to J&K. None of the case-related papers, including the sanction accorded for their prosecution, are publicly available.

It remains to be seen if the court finds in the evidence presented before it any ingredients of the offences of which these two public-spirited citizens stand accused. The experience in recent years indicates that any person commenting about these matters, let alone supporting them, becomes the immediate target of troll mobs on social media and jingoistic anchors on electronic media platforms and is labelled an ‘anti-national’.

But what do we make of the views of the gentleman who played a crucial role in the process of securing J&K’s integration with India in 1947 and also favoured freedom for that part of the sub-continent in the long run? On the 76th anniversary of J&K’s accession to India, this little-known vignette from that turbulent phase of modern Indian history is being presented with the fond hope that issues like “freedom” and “self-determination” are debated with a lot more care and maturity. The aspiration to be recognised as the “mother of democracies” must be accompanied by credible efforts to recognise and understand, not stifle and penalise, the expression of divergent views in the public domain.

Readers are aware of the crucial role which Vappala Pangunni Menon (V.P. Menon) played in bringing together the 500-odd princely states, zamindaris and the provinces directly administered by the British Raj to form the Union of India between 1947 and 1949. Initially as secretary to the Ministry of States and later as its Special Advisor, he achieved this formidable task under the leadership and guidance of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the Iron Man of India.

In his seminal work, The Story of the Integration of Indian States, Menon narrates the circumstances which led to J&K acceding to India. While recounting the bare facts about the flurry of meetings in Delhi and his own hurried travels to J&K in October 1947 to secure its accession, he intentionally abstains from sharing his own views about these matters in order to keep the narration of facts as objective as possible. However, his personal views about J&K have been documented for posterity in the official record of the deliberations of the Defence Committee of the Government of India in 1947.

It is public knowledge that Menon flew to Srinagar on October 25, 1947 on the instructions of this Committee. Its 8th meeting held earlier that day was chaired by governor general Lord Mountbatten, and attended by prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, deputy prime minister Sardar Patel, defence minister Sardar Baldev Singh, finance minister R.K. Shanmukham Chetty and the minister-without-portfolio N. Gopalaswamy Ayyangar. The heads of the three defence forces, and a host of secretaries and advisors representing key ministries were also present. The previous day, the deputy prime minister of the princely state of J&K, R.L. Batra, had arrived in Delhi with an SOS message from Maharaja Hari Singh as hordes of tribes were pouring in from across the northwestern border, committing murder, rape, arson and looting in village after village and town after town. They were less than 50 miles away from Srinagar.

Menon’s mandate was to discuss with Maharaja Hari Singh, among other things:

- the possibilities of J&K requesting armed assistance from India to defend the territory from the marauding infiltrators;

- cooperation between the government of J&K and the National Conference led by Shaikh Mohammed Abdullah; and

- J&K’s willingness to accede to the Dominion of India.

Menon flew back to Delhi on October 26 after meeting the maharaja in Srinagar and advising him to move to Jammu with his family for the sake of their safety. He reported his observations to the Defence Committee at its 9th meeting held the same day. The Committee advised him to fly back to Kashmir to secure J&K's accession to India. The exact date and time of his next round of travel to J&K have become a matter of controversy thanks to the varying narratives published by Indian and foreign historians and authors. I hope to comment on this issue later this year, based on archival research.

Also Read | The Backstory of Article 370: A True Copy of J&K’s Instrument of Accession

However, publicly available official records and narratives are unanimous about the fact that Lord Mountbatten accepted J&K’s Instrument of Accession on October 27, 1947 when it was presented to him with the signature of Maharaja Hari Singh. Its text and the maharaja’s letter explaining the dire situation that had arisen in J&K were published in the pages of local and foreign media on October 28. It is in the record of the Defence Committee’s 10th meeting held on that day that Menon’s personal and unequivocal opinion about J&K’s future can be found. The chain of the conversation is summarised briefly below.

Minutes of the 10th meeting of the Defence Committee held on October 28, 1947 by The Wire on Scribd

The Defence Committee discussed at length the progress made by the Indian defence forces which had landed in Srinagar the previous morning. Then the deliberations moved on to comparing the situation in Junagadh, Gujarat whose ruler professing the Islamic faith was inclined to accede to the Dominion of Pakistan whereas the majority of the population were Hindus. In contrast, J&K had a very large population of Muslims but was ruled by a Hindu Maharaja. Lord Mountbatten was of the view that India was in a strong position because it had declared its intention of ascertaining the will of the people in Kashmir on final accession as soon as the law and order situation there allowed it. So, it would automatically follow that Pakistan would accept a similar procedure for Junagadh.

Prime Minister Nehru opined that India’s position vis-à-vis the states as a whole would improve enormously if things went well in Kashmir and would be correspondingly weakened if there was excessive delay in clearing up Kashmir and if India became entangled there for a long period. Sardar Patel said that as far as world opinion was concerned, the longer the Junagadh situation was prolonged, the bigger an issue and more insoluble it would become. Shanmugam Chetty pointed out that world opinion usually ends up on the side of the victorious party in any clash. He said that military preparations should be made in Kashmir for any hostile action on the part of Pakistan.

Gopalaswami Ayyangar remarked that India’s case in both Kashmir and Junagadh was very strong from a political point of view. General William Lockhart, the then commander-in-chief of the Indian Army, said he saw Kashmir developing into a very big commitment indeed. He also said it was doubtful whether it would be in the power of the Indian Army to restore law and order in the whole of Kashmir if it became a question of that.

Prime Minister Nehru added that the task of eventually clearing Poonch was likely to be a terrific job [sic] and that it could probably not be taken up at all until the winter was over. Lord Mountbatten pointed out that British officers would not be available to help in a plebiscite in Kashmir, the following spring. He advised that the UN or the UK government be asked to send out officials to help with the plebiscite in Kashmir and Junagadh.

This is the point at which the minutes of the Defence Committee meeting record V.P. Menon’s views on what he expects to be Kashmir’s best-case scenario for the future:

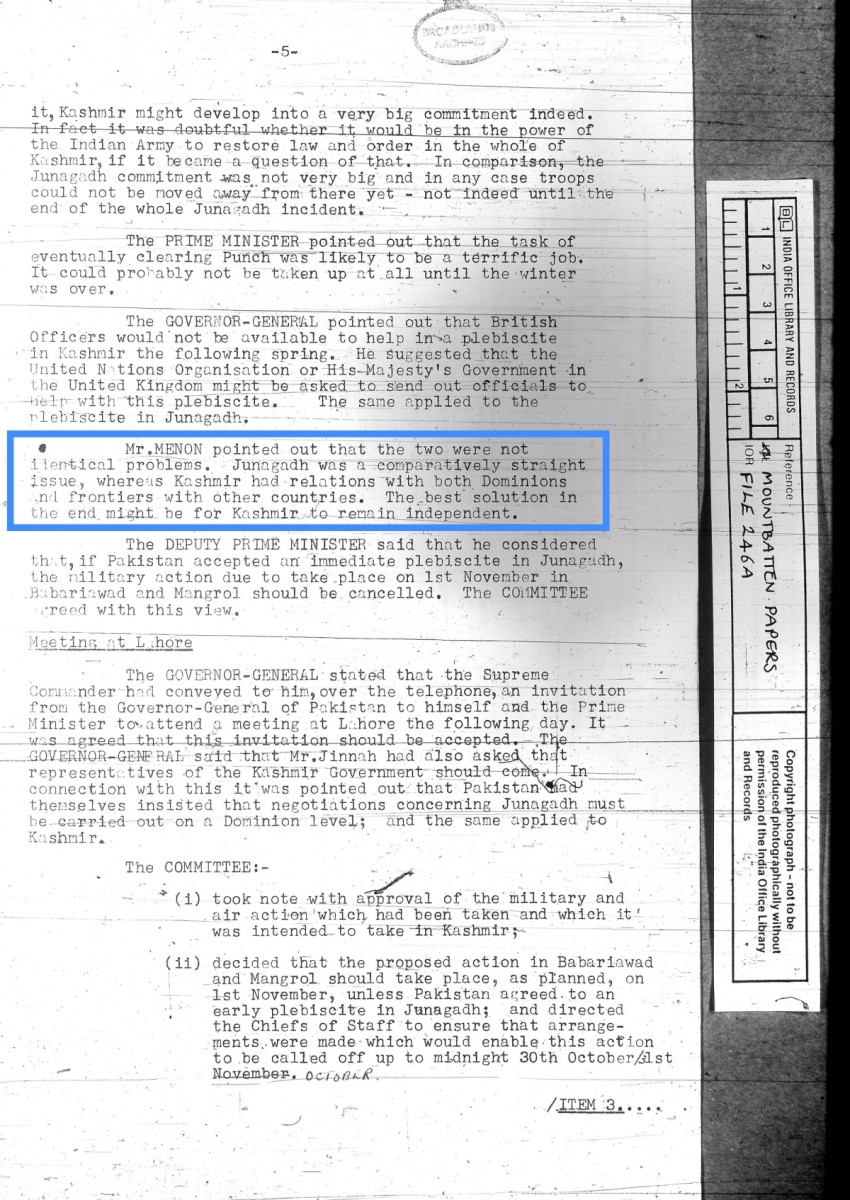

“Mr. Menon pointed out that the two were not identical problems. Junagadh was a comparatively straight issue whereas Kashmir had relations with both Dominions and frontiers with other countries. The best solution in the end might be for Kashmir to remain independent.” [Emphasis supplied)

Page 5 of the Minutes of the 10th Defence Committee meeting held on October 28, 1947. Photo: Author provided

Nothing in the minutes show either Sardar Patel, under whose guidance and instructions Menon worked, or Prime Minister Nehru or Lord Mountbatten or other participants rebuking him for talking about Kashmir’s independence. The ink on the Instrument of Accession signed and accepted less than 48 hours ago had barely dried when Menon spoke his mind.

Now why is this vignette of history important in 2023? Had Menon been alive today and uttered these views, would he not be accused of supporting ‘separatism’? Would his patriotism and commitment to India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity not be thrust under a public scanner ignoring his yeoman contribution to unify India territorially and administratively? Would he not be trolled as a member of the so-called ‘tukde tukde gang’ on social media? Would he not be hauled up for ‘sedition’ and for ‘making assertions against national integration’ in the manner of Arundhati Roy and Sheikh Showkat Hussain? Or will the foot soldiers of a certain ideological disposition now conduct a media trial of V.P. Menon posthumously and move him from the ranks of ‘patriots’ to those of ‘anti-nationals’?

This vignette of history serves as testimony to the extent of freedom of speech and expression that existed in independent India even when the constitution had not been put in place to protect it. There was space within the highest government circles for voicing divergent views without fear of reprisals. Do similar spaces for the expression of contrarian views exist within and outside government circles today, in the era of nasty trolling and fake news peddling? This is what every citizen must be deeply worried about.

Perhaps the biggest irony of the Roy-Hussain episode is that the gentleman who accorded sanction for their prosecution himself stands accused of committing serious offences such as assault, wrongful restraint, criminal intimidation and being part of an unlawful assembly, along with three other politicians in a case that is more than 21 years old. Noted environmental activist and advocate for the rights of people displaced by developmental projects, Medha Patkar of the Narmada Bachao Andolan, was allegedly assaulted by this quartet at, believe it or not, Gandhiji’s Sabarmati Ashram in 2002. While the Delhi high court refused to stay the criminal trial on his plea that he is required to perform his constitutional duties as the Delhi LG, the Gujarat high court granted his plea earlier this year. In an ideal world, such a person ought to have voluntarily stepped down from the constitutional office to face trial instead of moving high court after high court for relief. But we are told, we are living in Amrit Kaal., not ideal times, right?

Venkatesh Nayak is an RTI activist and a history researcher based in New Delhi. Views are personal.

This article went live on October twenty-seventh, two thousand twenty three, at zero minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.