Watch all episodes here: 1. A Brief History of a Civilisation and Why We Need to Know it | 2. The Aryans and the Vedic Age | 3. The Mauryans and Megasthenes | 4. The Ikshvakus of Andhra Pradesh. | 5. Nalanda and the Decline of Buddhism | 6. Khajuraho and the World of Tantra | 7. Alberuni and Marco Polo in India | 8. The Vijayanagar Empire | 9. The Mughals and Bernier | 10. The Faiths of Varanasi.

Khajuraho was the capital of the Chandelas, who built 85 temples between 900 and 1150 CE. The 25 that survive are now famed for their fine sculpture, including graphic sex on their walls. In the late first millennium, such temples arose across India, at Badami, Mathura, Konark, etc. Who built them and why? What sort of a worldview puts explicit sex next to their gods? How did a dominant religious culture that glorified austerity, renunciation, and asceticism as the path to God, accept such sexual imagery – on temples, no less? And how did Indians of that era turn into today’s woeful prudes easily scandalised by such erotica, no hint of which appears on their modern religious monuments?

Clearly, Indian religious culture then was very different. A key difference was Tantra, whose pre-historic roots go back to non-Aryan folk traditions. Tantra revered the idea of fertility, and saw sexual love as a path to spiritual progress and liberation. Rising from below, Tantra fused with Jainism, Buddhism, the Puranic sects of Shaiva, Vaishnava, and Shakta, and inspired sexual imagery on their monuments.

The sex-positive, anti-caste, and goddess-centric folk culture of Tantra was also the soil that sustained the secular hedonism of the elites and the Kamasutra. But then came a huge conservative blowback within Hinduism that decimated Tantra. Discover the lost world of Khajuraho, the influence of Tantrism in early medieval India, and its decline.

Below is the transcription of the entire episode.

Hello and welcome to Indians. I’m Namit Arora.

In the previous episode, we looked at Nalanda, the accounts of three Chinese travellers, and the decline of Buddhism in India during the second half of the first millennium. This was a time of great social and religious churning. Today I’ll look at how this played out at Khajuraho, a site now famous for its amazingly beautiful temples that also show graphic sex on their walls. Such temples were built across India. Who built them, and what were they thinking? What led them to combine religious moods with sex? And why do modern Hindus and their temples lack this worldview entirely? I mean, what happened to us?—how did we go from there to this country of prudes! I’ll tackle all that—and more—in this episode.

The Discovery of Khajuraho

Khajuraho was the capital of the Chandela kingdom (c. 831–1315), where the Chandelas built 85 temples, mostly between 900–1150. Twenty-five of these temples have survived. They had been buried in a forest for centuries until their rediscovery in 1838 by a British engineer, who was scandalised by the sexual imagery. He called the sculptures ‘indecent and offensive’ and wondered how any chaste religion could permit such depictions. Alexander Cunningham, who founded the Archaeological Survey of India in 1861, called them ‘disgustingly obscene’. Clearly, these were men of the Victorian era.

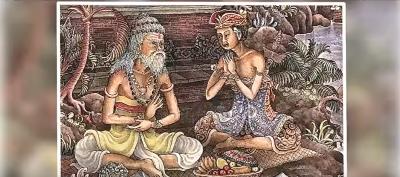

But these temples feature a lot more than sexual scenes, which make up less than ten percent of their sculptures. They also show a wide range of major and minor gods. Secular subject matter abounds, including young maidens in a variety of moods and activities, teachers and disciples, dancers and musicians, royal hunts, marching armies, battle scenes, animals like elephants, parrots, snakes, and much else.

The Enigma of Erotic Art on Temples

But it’s the erotica that’s most puzzling. What sort of a worldview puts hardcore sex next to their gods? It challenges our thinking about religious art and ‘proper’ spiritual moods and sentiments. These temples depict not just heterosexual coitus but also masturbation, orgies, oral sex, lesbian and gay sex, exhibitionism, and even bestiality. The panels depict youthful men and women with idealised bodies, but also bearded, rudraksha-wearing, pot-bellied ascetics, acharyas, and yogis having sex—a far cry from today’s idea of these roles. In fact, modern Hindu temples do not show any sex at all. So what’s going on here?

And Khajuraho was not unusual for its time. Many medieval temples across India carried such depictions on their walls and even in their inner sanctums—at Badami, Bhubaneshwar, Konark. How did a religious culture that had long glorified austerity, renunciation, and asceticism as the path to God, approve of such sexual imagery—on temples, no less! Most Indians today are so prudish that they’re scandalised by this imagery; it’s almost alien to them. I mean, kissing scenes came into Bollywood barely a generation ago, and we still can’t watch them with our parents in the same room. So what motivated our medieval ancestors to create this? What was its meaning back then? And why did it disappear?

Was Temple Art Inspired by the Kamasutra?

Some people say, oh, it was a liberal age, the time of the Kamasutra, when Indians had few sexual hang-ups. The sculptures, they say, are a visual illustration of the Kamasutra, and were commissioned by libertine aristocrats. But this is a lazy answer, and it collapses if we think about it carefully.

The Kamasutra is not a religious or spiritual text. It is about the earthly art of love and courtship. Its audience was the urban upper crust who pursued erotic pleasure as an end in itself. It dates from the early first millennium, near the dawn of the Gupta Empire. Though attributed to Vatsyayana, it’s really a composite work that had evolved over centuries. Back then, many other texts advised people on sexual love, courtship and even adultery. The Kamasutra is only the best known of them. In many ways, it’s a very patriarchal text, and the modern reader will find in it plenty of regressive views.

But the Kamasutra can also be surprisingly progressive. For instance, it sees women as full participants in sexual life, as individuals gladly engaging in an exciting social game. It is attentive to a woman’s feelings and emotions that a man should understand to increase erotic pleasure. It stresses the importance of grooming, etiquette, diplomacy, and post-coital conversation. It’s not just a manual for men; it also offers advice to maidens, courtesans, wives, and mistresses. It advocates marriages based on love over arranged ones, and it discusses practical matters like how to find a partner and maintain power in a marriage. It does catalogue a range of sexual positions—some impossibly athletic ones!—but it’s really a treatise on the art of intimate relationships.

As a secular treatise, the Kamasutra can at best explain erotic imagery in private spaces, on personal objects like combs, paintings, or ivory panels. It does not explain why it was alright to put graphic sex on temple walls, next to the gods. Why would the royals put erotica on state temples and risk offending their subjects? So what explains these depictions?

The Tantric Substrate

We first have to remember that religious culture back then was very different from ours, which is why it seems alien and scandalous to modern Indians.

One key difference was Tantra—a religious worldview whose pre-historic roots lie outside the Vedic and Buddhist fold. Tantra comes from non-Aryan folk traditions, in which people revered the idea of fertility and had built magico-religious practices around it. Their symbols of fertility evoked male-female unions. The yoni-lingam is one example. Some symbols were abstract, others were more concrete. They appeared on private votive offerings to fertility goddesses. A young couple aspiring for a child might offer such terracotta plaques to a goddess like Sri.

From the Mauryan era, the images on these plaques became more literal. They showed amorous couples—some even in the act of mating. Depictions of fertility goddesses, including the lotus-headed Lajja Gauri, also became popular on discrete objects.

In time, these symbols of fertility started migrating from small, private objects to the public sites of dominant religions. The earliest such fusion of sexual and religious imagery that we know of, appeared on the stupas of Sanchi and Bharhut. But these early depictions on large monuments were still tame and mainly showed voluptuous yakshis, who were associated with fertility.

It’s safe to say that the inspiration for this religious fusion came not from the Buddha, but from the syncretic milieu of the common people who built such monuments. They liked the Buddha’s message, but they also revered their traditional fertility cults and symbols. Placing them on Buddhist sites made Buddhism even more appealing to them.

During the first millennium, Tantrism evolved into a complex set of beliefs and meditative practices. It was a non-dualistic system that embraced the whole human being—mind and body—in spiritual practice. This made it very different from Brahminism, Buddhism, and Jainism, because central to these three was the idea that worldly temptations, cravings, and physical desires are impediments to spiritual growth and liberation. They idealised asceticism and renunciation. But Tantrism took the opposite view. It valued worldly success and held that spirituality was intertwined with success in love. In Tantrism, properly guided sexual love was a path to spiritual progress and eventual liberation, or moksha. In other words, sexuality was a path to the divine.

The Rise of Erotica on Religious Monuments

It was Tantrism that furnished a worldview in which sex and religion were unified pursuits. It rose from below and fused with popular Puranic sects of Shaiva, Vaishnava, Shakta, as well as Buddhism and Jainism. To varying extents, Tantric sexual and yogic practices became common in religious life after the mid-first millennium. The goal of such practices was not hedonism but a higher state of awakening. Many upper-class folks also embraced this sex-positive religiosity, which then paved the way for sexual art on monumental religious sites.

In the early centuries of the Common Era, partly influenced by Greco-Gandharan art, greater realism and sensualism appeared in monumental stone art in India. As with the private votive objects earlier, the fertility theme on temple walls was initially evoked using couples holding hands or embracing. Such amorous pairs soon became an auspicious and decorative motif, or alankara, on the monuments of all major religions. They appeared on temples across India, in Mathura, Gujarat, Mysore, Ajanta, Ellora, Badami, Aihole, Pattadakal, and Bhubaneshwar.

In time, these public depictions grew more graphic, as they had done earlier on private votive offerings. The earliest sculptures with couples having sex appeared on religious monuments in the mid-first millennium CE. They were initially small and discreetly placed. But the size, finesse, and centrality of erotic art on temples kept growing until it became an artistic convention. Not surprisingly, this paralleled the rise of Tantrism, which had infiltrated all major religious sects like Shaiva, Vaishnava, Shakta, Buddhist, and Jain. And it had infused in them its spiritual concepts for mixing sexuality with divinity.

It’s important to note that these depictions did not shock or scandalise the public because they had come from grassroots beliefs and the familiar imagery of votive offerings. The public would’ve seen in these temple sculptures a sense of beauty, divine order, auspiciousness, fertility, and prosperity. In other words, these sensual images were meant to comfort—not offend or challenge—the sensibilities of the temple-goer. The royals who sponsored such sculptures on religious sites hoped mainly to convey a stable, harmonious vision of life—and to acquire merit, fame, and legitimacy for their rule.

Khajuraho’s Religious Landscape

In the Chandela realm, there was virtually no Buddhism, which had already receded to a few pockets in eastern and southern India. Khajuraho had a mix of Tantric-Puranic faiths that had also absorbed many Brahminical ideas—its rituals, texts, caste rules, Advaita thought. Scholars would later call this religious soup ‘Hinduism’. It was this, shall we say, ‘Original’ Hinduism, plus some Jainism, that made up the religious landscape of Khajuraho.

To the subscribers of this ‘Original’ Hinduism, depicting sexual couplings next to Puranic deities was a perfectly harmonious thing to do. That’s exactly what the Chandela royals commissioned on state-sponsored temples. And once it began, other mundane factors drove more sex on their walls. Temples competed for visitors, prestige, and donations, so they stood to gain by literally amping up their sex appeal. A Shilpa Shastra text of the day, a canon of architecture, saw religion as partly entertainment and mentioned the use of erotic temple art for the ‘delight of the people’. More kinds of erotica made temples more amusing and popular. In time, a competitively playful dynamic took hold, and a wider range of sexual scenes appeared on temple walls, including some that had nothing to do with the idea of fertility.

The Erotic Lives of the Rich & Famous

The Tantric folk substrate of early medieval India was immensely sex-positive. It was also the soil in which the secular hedonism of the aristocrats thrived. This was especially true of the Chandelas, who probably had a natural affinity to Tantric ideas and symbols, since they came from lower social ranks with tribal associations. They were an upwardly mobile group who, with the help of Brahmins, had successfully invented and legitimised a Kshatriya genealogy that made them Rajputs of the lunar line, or Chandravanshis.

The Chandelas and other ‘Kamasutra elites’ pursued erotic pleasure as a secular end in itself. In theory, Tantric sexual practices had higher spiritual ends but many pleasure-loving aristocrats—and their obliging gurus—reduced it to mere hedonism. Wealthy men sought the company of courtesans, who were educated, cultured, upper-class women proficient in the ‘sixty-four arts’ of refinement, like music, dance, and the art of love. Though roundly condemned by orthodox Brahmins, these courtesans lived in posh areas of the city, could choose their clients, and were often seen as celebrities. Many kings and aristocrats kept concubines and took them on hunting trips, picnics, water-sports, summer resorts, and even battles. Prostitution was both legal and taxed. The state punished rapists, which might include physically branding them.

For aristocratic men, a highly coveted life experience was an extramarital affair with a married woman. Their wives also had affairs. In royal parties, women and men consumed alcohol in each other’s company and mingled freely. In official eulogies and inscriptions, kings were described as great lovers. They kept harems with women from all over India and even Africa and Arabia. Sanskrit poets and erotica writers of the day delighted in describing the sexual charms of women from different regions. Aphrodisiacs and sex potions were much in demand.

Many medieval temples recruited devadasis, or young women who learned dancing, singing, music and theatre, which they performed publicly at the temples. They pioneered and innovated many forms of art, such as the dance form Sadir, a precursor to Bharatanatyam. Many devadasis earned wealth and fame, but many also served as prostitutes to temple priests, pilgrims, state officials, and the royals. Clearly, worshipping gods wasn’t always top of mind for folks associated with temples.

The common people too had fewer hang-ups about sex and courtship when compared to their counterparts today. During certain revelries and festivals of fertility—amid alcohol, song, and dance—a wider cross-section of the public let their hair down and ignored conventional restraints on sexual morality—of caste and class, for instance. Married men and women were said to pursue one-night stands.

The Brahminical Backlash

Tantrism itself had many sects with differing beliefs and practices. Most were mild or moderate and were socially integrated. Some Tantric gurus even advised kings on their sex lives and held high positions in temple organisations. An extreme sect of Tantrics was the Shaiva Kapalika, from whom today’s Aghori babas come. Its members led aloof and solitary lives, and took delight in transgressive acts and breaking taboos. They hated Brahmins and often used a Brahmin’s empty skull as an eating or begging bowl. No wonder the Brahmins hated them back.

None of this sat well with orthodox Brahminism, which had long had a strain of sexual prudery. The sexual mores of the Tantric substrate troubled the Brahmins. The Tantric path of achieving liberation through ritualised sex clashed directly with the austere path advocated by the Vedas. Tantra venerated goddesses that were often fierce, powerful, and independent of male gods. It accorded higher dignity to women, who could also perform its sacred rituals. Tantra welcomed all castes, condemned practices like the caste system and sati, and disregarded notions of ritual purity and pollution. Not surprisingly, Tantrism clashed with Brahminical conservatism.

The Decline of Tantrism

Such conflicts are partly why the Tantric substrate almost died out in much of India. It’s a fascinating story with two major developments. First was the rise of the Bhakti Movement in south India that preached mystical love, devotion, and surrender to a personal god. It was an outgrowth of folk religiosity that looked down on worldly pleasures. Its folk origins meant that it shared many anti-Brahminical and gender-egalitarian instincts with Tantra, but not its sex-positive spirituality. Instead, the Bhakti Movement held devotion as the path to the divine.

Second was a revival of Brahminical orthodoxy by the influential theologian, Adi Shankara (est. late 8th cent.), a Namboodri Brahmin whose ancestry was north Indian. A staunch conservative and a proponent of Advaita Vedanta, his key innovation was to cleverly appropriate all Puranic cults under Brahminism by declaring gods like Vishnu, Shiva, Shakti, Ganesh, and Surya as forms of the one and only Supreme Being. In other words, he created a framework in which various Puranic cults and devotional practices got subsumed under the Brahminical cosmology of a Unitary Godhead, or Brahman.

Adi Shankara’s Brahminical revivalism and the Bhakti Movement greatly increased the ranks of the orthodox and the prudes. They first squeezed out Buddhism and then the sex-positive Tantric religiosity. This was a huge setback for intellectual culture and creativity in India. By the end of the first millennium, Indian society was well on its way to becoming more conservative, devotional, puritanical, hierarchical, and patriarchal.

What caused this decline were fault-lines and conflicts within Indian religious culture. We can see this in the literature of the period, such as the Chandela court play, Prabodha Chandrodaya (or ‘moon rise of true knowledge’). It’s an allegory written by Krishna Mishra and was staged in 1065. In this play, Brahminical forces unite and rail against the non-Vedic forces of Tantrism, Buddhism, Jainism, and the Carvakas. Such views were gaining ground not only in the Chandela court, but across most Indian dynasties in the late first millennium.

The Long Conservative Turn

As Tantra declined, so did the depictions of sex on temple walls. Little of this style of art was commissioned after 1400. For instance, one finds very little sex on the temple walls of Vijayanagar. A strong link between sex and religion was broken. Erotic visual art retreated to private spaces and personal objects. The Kamasutra too fell into obscurity. Fewer Hindus now had casual sexual escapades, wrote erotic poetry, or married out of caste. Large numbers were drawn to Bhakti and the devotional ecstasies of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Mirabai, Eknath, Tulsidas, and Surdas.

The very role and function of temples in public life began changing to mere places of worship, partly also as their wealth and patronage declined under Indo-Muslim rule. Tantra receded to the fringe, where it survives to this day. We no longer find sex on modern urban temples, but we can still see sculpture like this in a recent Shiva-Parvati temple at the foothills of Niyamgiri Hills in the tribal belt of Odisha.

With the decline of Tantrism, the status of women worsened too. Control of women’s sexuality increased to maintain the sanctity of caste. The goal of sex moved closer to procreation, as in the Manusmriti. In parallel, the centrality of goddesses declined too—or rather, the goddesses nominally remained, but gradually became ‘consorts’ to male gods, basically, sidekicks. They became sweeter and tamer. Such as Pampa, once a powerful tribal goddess of the Hampi region whose husband Virupaksha was a relatively minor god, until their status got flipped. This status reversal accompanied their induction into the Brahminical pantheon as forms of Parvati and Shiva—an increasingly common story across India.

This conservative turn was led by forces within Hinduism, long before the rise of the Delhi Sultanate around 1200. Of course, Indo-Muslim elites were no friends of Tantra either. In their attitudes to sex, orthodox Hindus and Bhakti saints were brothers under the skin with orthodox Muslims and Sufi saints. So were the Christian British, who neither helped the cause of Tantra, nor fairly assessed its place in the history of Indian religious thought. With Brahmins as their native informants, the British incorrectly placed Brahminical texts at the core of historical Hinduism. This suppressed the awesome religious diversity of India.

Not surprisingly, the Victorian British of the colonial era rejuvenated Hindu conservatism. We got men like Vivekanada and Gandhi, with their famous hang-ups about sex. Hindu goddesses got wrapped up in clothes, and artists who didn’t comply were harassed for hurting ‘religious sentiments’. Such prudishness would have drawn amused laughter from Khajuraho’s religious leaders a thousand years ago.

And now reactionary Hindu nationalists make vapid claims about a sanatan, or ‘eternal’, Hindu religion that was supposedly always pure, chaste, and sexually austere. They rage against Valentine’s Day, demand sexual modesty from women, and even harass couples who indulge in public displays of affection. And they do this, without irony, in the name of preserving Indian tradition! One imagines countless medieval Indians turning in their graves.

The Fall of the Chandelas

The Chandelas were often at war with others—the Chedis, Chalukyas, Chauhans, and once even the formidable Mahmud of Ghazni, who the Chandelas pushed back in 1022—an event they celebrated by commissioning their grandest temple, the Kandariya Mahadeva. In the 13th century, they became a vassal state to the Delhi Sultanate and their power kept declining. They abandoned Khajuraho and retreated to a distant hill fort (Kalinjar). Khajuraho was no longer a power centre, partly why its temples did not become a target of political rivals. In the 14th century, Khajuraho dropped out of history and public memory, and was consumed by the forest. It would become one of the greatest ‘lost cities’ of India.

In the next episode, I’ll explore the accounts of two amazing travellers—Alberuni and Marco Polo—who came to India in the early centuries of the second millennium and made insightful observations about Indian society and culture. See you next time!