Anganwadi Workers Are Fighting Against Unusable Tech – Just to Be Able to Do Their Work

Anganwadi workers are agitating in Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, for a range of issues be addressed – from increase of wages, and lack of pension to other retirement benefits and regularisation of their services.

These protests are also stemming from their anger towards increased push of digitisation under the PM-Poshan Abhiyaan, where Anganwadis' role of caregivers has been turned into that of data collectors. The honorarium paid to Anganwadi workers has also been linked to data entry into various apps under the PM-Poshan Abhiyaan.

A World Bank-assisted programme, PM-Poshan Abhiyaan aim to decrease stunting among children and reduce anaemia among women to reduce low birth weight. Anganwadi workers play an important role to provide early care for pregnant women, along with child care, by providing nutritious food and educating children in pre-schools. For this work, Anganwadi workers are paid a honorarium of around Rs 10,000 per month, while Anganwadi helpers are paid Rs 7,000 per month. The latter are considered volunteers under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) Scheme.

A World Bank-assisted programme, PM-Poshan Abhiyaan aim to decrease stunting among children and reduce anaemia among women to reduce low birth weight. Anganwadi workers play an important role to provide early care for pregnant women, along with child care, by providing nutritious food and educating children in pre-schools. For this work, Anganwadi workers are paid a honorarium of around Rs 10,000 per month, while Anganwadi helpers are paid Rs 7,000 per month. The latter are considered volunteers under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) Scheme.

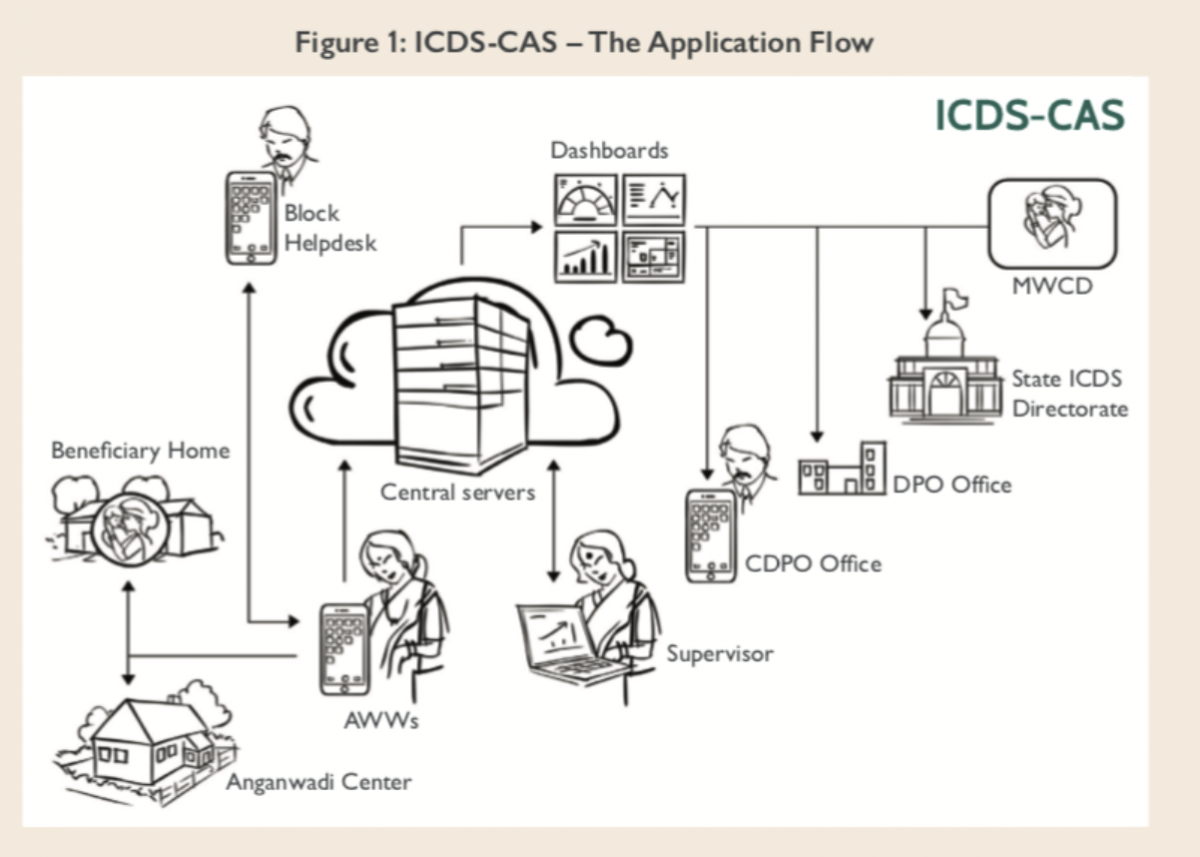

The PM-Poshan Abhiyaan scheme introduced digitisation of all activities of Anganwadis using mobile application technologies. This digitisation process started with ICDS - Common Application Software (CAS), which pushed for digitisation of nutrition monitoring and growth monitoring of children, by facilitating data collection for decision making.

The ICDS-CAS was augmented with the launch of PM Poshan Tracker, which brought in a new paradigm of 360° profiling of Anganwadis and real-time data collection. The idea of real-time data collection was to function as a feedback mechanism to help improve local decision making.

Application flow of the ICDS-CAS mobile application. Photo: World Bank

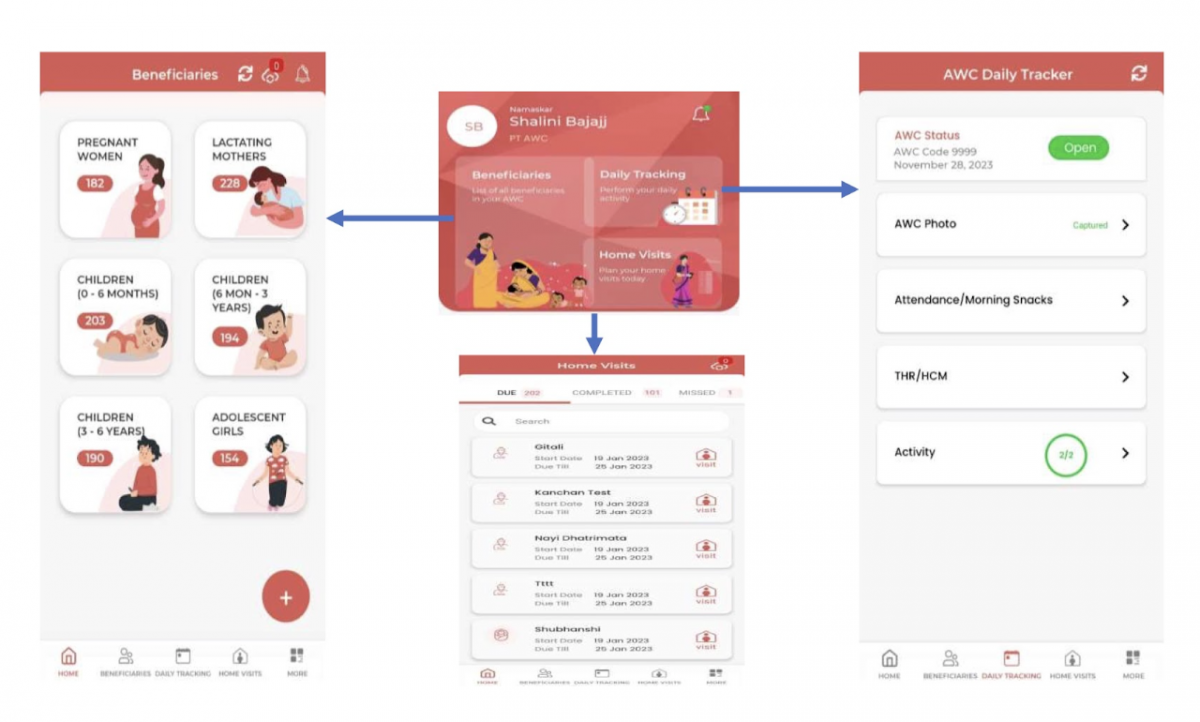

The push for PM Poshan Tracker increased data collection by Anganwadis with every update of the application.

With various modules for pregnant women, lactating mothers, children of different age groups and adolescent girls, the app increased the burden of data collection from the Anganwadis to track real-time daily attendance and monitoring. Workers in Andhra Pradesh are being constantly pressured to fill the application every day to show "100% statistics" by their supervisors.

PM-Poshan Tracker app flow. Source: PM Poshan Tracker https://www.poshantracker.in

As part of the PM-Poshan Abhiyaan, Anganwadi workers were provided smart phones under the ICDS budget with a price cap of Rs 8,000 per mobile device, which were later revised to Rs 10,000 per device with updated specifications. These mobile devices which can only be procured through the Government e-Marketplace (GEM) and have consistently failed to function leading to Anganwadi workers being unable to enrol the beneficiaries and enter data that they were forced to collect.

With the threats of being removed from work and the lack of payment of honorarium for being unable to upload data through broken phones, the Anganwadi workers in Maharashtra approached the Bombay high court seeking relief. The court taking the issue of broken smartphones into consideration, ordered the government of Maharashtra to replace them with functional ones. The ICDS authorities also installed mobile-device management (MDM) tracking software to track all action performed by Anganwadis on these phones in Maharashtra.

As part of the litigation, the Anganwadi workers highlighted accessibility issues of the mobile application – the apps are only available in English and not in Marathi. The ICDS Commissioner and government of Maharashtra even opposed this as they wanted the Anganwadi workers to enter names of beneficiaries in English for the de-duplication process powered by Aadhaar. This strange assertion in courts that they can only de-duplicate beneficiaries in English shows how the state itself does not understand Aadhaar and how to apply it.

While the Anganwadi workers in Maharashtra have been fighting against ICDS software applications in courts, their counterparts in Andhra Pradesh have been similarly struggling with increased burden of these new applications. In Andhra Pradesh, beyond the PM-Poshan Tracker, workers are required to use an array of other mobile applications to create indents for supplies like eggs, milk and other food supplies from the government of Andhra Pradesh as part of their real-time governance strategy.

There have been constant complaints from workers on how these mobile applications and their servers do not often function. The Anganwadi workers are being asked to wake up in the middle of the night to upload data on apps, as the servers are not busy during the night. For the Child Development Project Officers and supervisors, unless the data on daily attendance and work has been collected, the Anganwadi workers have not completed their work for the day.

The distribution of mobile phones to Anganwadi workers means that they have to be constantly available over phone to respond in real-time to the supervisors. These supervisors who look at their dashboards everyday in the morning, want to ensure the pre-schools open on time, attendance of kids is recorded on time and every other activity happens on time too.

This is the core aspect of real-time governance being employed by Andhra Pradesh and the government of India. For real-time governance to occur, workers have to be available to work real-time. But they are unable to focus on work with broken apps and pressure from supervisors to constantly log work. Real-time governance demands workers act as robots who are constantly doing their task while responding to instructions too.

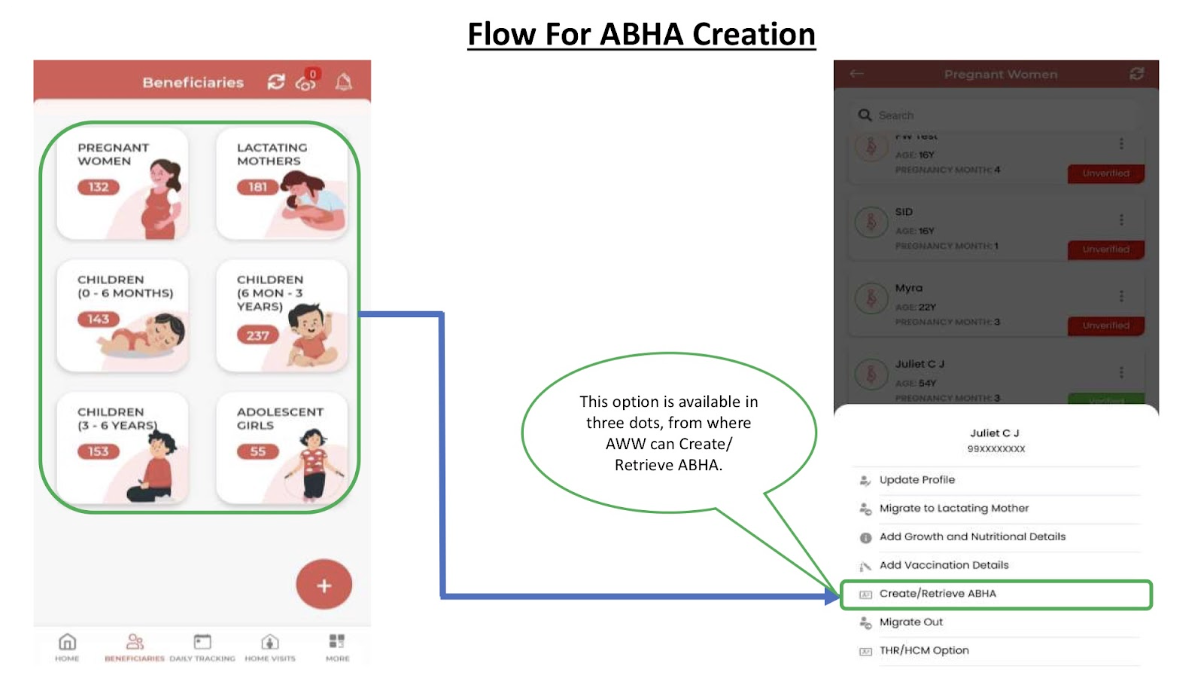

There is a constant push for the Anganwadi workers to collect new forms of data, the PM-Poshan Tracker has new modules to create health IDs of every beneficiary under the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission. All the data collected about children and pregnant women is now being stored using electronic health records. The creation of beneficiary profiles is the core aspect of 360° profiling being imposed by the state.

PM-Poshan Tracker app flow. Source: PM Poshan Tracker https://www.poshantracker.in.

In Andhra Pradesh, the Anganwadi workers have been given a new task of collecting facial biometrics of every beneficiary and to use them for authentication using facial recognition. The push away from Aadhaar to facial recognition in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have been primarily because of the failures and fraud emerging from fingerprint recognition with Aadhaar.

Anganwadi workers have been facing a hard time in collecting and authenticating using AP’s facial recognition system AP-FRS. One of their demands, part of the protests, is to stop imposing the facial recognition system for beneficiary identification. A report from The Hindu highlights how this system has been failing, leading to pregnant women being forced to walk to the Anganwadi centre, for authentication, if the FRS is unable to authenticate them on the field. The constant failures in authenticating beneficiaries means Anganwadi workers need to work longer.

Workers are being forced to upload data into multiple apps by the Union and state governments. This has increased their work further with no data sharing agreements between the Union and states. The Anganwadi workers also maintain a physical ledger as these apps do not function all the time. This breeds a complex web of multiple records. One of the demands from Anganwadi workers is to create a single app instead of demands of multiple entries into different apps.

Beyond the data collection the workers are being additionally forced to conduct promotional activities by the government like Yoga Day. These new events and activities are added as new modules in the apps. The state continues to track whether these activities have been conducted or not through various apps, demanding digital evidence of participation of people.

PM-Poshan Tracker app flow. Source: PM-Poshan Tracker https://www.poshantracker.in

Contrary to popular beliefs of technology improving and easing the work for Anganwadi workers, these apps have had the opposite effect. The applications and various modules of the application constantly demand new forms of work from workers who are not trained under these tasks. These issues are universal for Anganwadi workers across India, who have been protesting over the last few years.

While the amount of work is being increased with every new module added into apps, the workers' wages have stagnated. Anganwadi workers are treated as volunteers who are signing for a voluntary activity, but are being forced to work like a full-time worker. They are not being provided any health, insurance or retirement benefits for this work either.

One of the major demands of Anganwadi workers in Andhra Pradesh is to allow them to receive government schemes that are being provided to the general population. With 360° profiling of households, any government employee household is automatically rejected for any state welfare schemes. In the case of Anganwadi workers, they are treated as government employees and cannot get state welfare. At the same time they are treated as volunteers and do not get employee benefits. This is what the workers are fighting for, to not be excluded by the state in every aspect.

India is rapidly digitising. There are good things and bad, speed-bumps on the way and caveats to be mindful of. The weekly column Terminal focuses on all that is connected and is not – on digital issues, policy, ideas and themes dominating the conversation in India and the world.

Srinivas Kodali is a researcher on digitisation and a hacktivist.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.