Mumbai: On December 4 last year, 36-year-old Antim Sitole, an Ambedkarite activist in Barwaha tehsil in the Khargone district of Madhya Pradesh, received a call from Suhas* from neigbouring Semalkhut village. Suhas pleaded that Sitole somehow rescues him and 26 others – including women and young children – from a farm in Belagavi, over 930 kilometres away in Karnataka. Suhas said they were held hostage in a sugarcane farm with no money and very little food. “You come right away, or we will soon die,” Suhas had told Sitole.

In October last year, soon after Dussehra, a contractor from Inchal region in Bailhongal taluka of Belagavi had visited Semalkhut and promised great pay and living conditions to villagers to work in a farm. Around 16 adults agreed to travel to Belagavi with him; they took 11 children along. A part amount was paid as “advance”, and every adult individual was to be paid Rs 400 for eight hours work per day, along with three square meals and a proper house to live in. Children were to only live along. “This sounded like a much better arrangement than any place we had worked before in Gujarat or Maharashtra,” Suhas told The Wire.

Instead, Suhas says, the families, including children as young as 12 and 13, were forced to toil on the farm for 16-19 hours, paid Rs 400 once a week per family for ration and pushed to live in squalor. They were beaten up, their phones confiscated and kept under surveillance 24*7, Suhas claims. At least three women, including Suhas’s wife and two young girls barely in their teens were allegedly raped repeatedly by the contractor and two of his associates right in the farmland they worked.

On receiving Suhas’s call, Sitole, a paraplegic man, bound to a wheelchair, travelled to Belagavi on December 8. He took two of his teenage sons and a nephew to help him in the journey. His wife pawned her jewellery to help him raise money for the trip. Before leaving, Sitole had contacted the local administration. “But they were taking too long to respond to my request. So, I just dropped a letter and headed straight to Belagavi,” Sitole says.

It took over a day for Sitole to get to Bailhongal. The contractors had meanwhile found out about the calls made and had confiscated Suhas’s phone. They were also swiftly moved to a new location. At Bailhongal, Sitole says, the police again took an entire day to send a team to the spot. “I knew if I had returned, the victims would not have been rescued. So, I spent the night outside the police station with my children,” Sitole told The Wire.

Antim Sitole, an Ambedkarite activist who helped 27 labourers escape from Belagavi in December last year. Photo: By special arrangement

On December 9, the police visited the location, found all victims toiling on private farmland. “They unanimously told the police that they had been ill-treated. But the police did not register any complaint,” Sitole says. He further adds that even in the police’s presence, the contractor and his men had intimidated the workers. “I was taken to an undisclosed place and threatened with dire consequences,” Sitole claimed.

Belagavi police limited its intervention to only letting the families return to their hometown. No first information report (FIR) was registered. “All rescued persons, including young children, narrated their stories before the police. But they (the police) made it appear that this is a common thing to happen to anyone working as a labourer and that we should only be happy to return home alive,” Suhas says.

Also read: How Punjab’s Dalit Labourers Are Trapped to Live a Bonded Life

A day later, on returning to Semalkhut, Sitole had taken all the victims to Chainpur police station. The police, however, refused to take their complaint immediately. “With great difficulty we could convince women and children (who were allegedly sexually assaulted) to travel from Karnataka back home without washing up. We were hoping that their medical examination would be immediately done and the evidence would be recorded. But the police did not budge,” Sitole says. An FIR was finally registered on January 6 only after Jagriti Adivasi Dalit Sanghathan (JADS), a Madhya Pradesh-based tribal and Dalit rights group intervened.

The FIR mentions only names of the contractors – Sunil Dharade, Govinda and Ganesh. The farm owner isn’t named. And more importantly, the sugar cooperatives – invariably owned by the powerful businessmen and politicians – for whom the contractors actually work are nowhere in the scene.

The FIR, the survivors say, has only added to their trauma. The girls and women survivors The Wire spoke to said that the police have called them to the police station many times and questioned them as if they were the violators here. “We have been made to relive our trauma time and again by the police,” Suhas’s wife shared.

After multiple rounds of recording of statements, the police, a fortnight ago, produced the women and child victims of the repeated sexual assaults before a magistrate to record their statements, under Section 164 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

The Wire contacted Nirmal Kumar Shrivas, the police in charge, to find out the latest update in the investigation. He claimed that because of COVID-19 pandemic, his team has not been able to go to Belagavi to arrest the accused person. When reminded that the accusations made are of serious nature, Shrivas said, “We can’t help. We are not allowed to travel outside the state because of the pandemic. Also, we are still trying to verify all the claims made by the complainants.”

The FIR has missed out on sections of the two crucial Acts – the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act and the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act (BLSAA). To this Shrivas said, “We have not found anything substantial to support this claim. Once we are convinced, we would enhance the sections.”

Multiple cases of bonded labour

Shrivas’s response is typical. No state wants to acknowledge the rampant practice of bonded labourers ever, points Madhuri of JADS.

Both the Belagavi administration and that of Khargone have tried to wash their hands of any responsibility as prescribed under the Act.

And the Adivasi migrants of Semalkhut were not the only ones to have been exploited in Belagavi. In the process of helping them legally, JADS came across multiple cases of bonded labour in western parts of Maharashtra and north Karnataka. After the Semalkhut incident, another 57 persons were rescued from Belagavi. After a lot of push backs and denial of accusations, the labourers managed to reach their village in Barwani district last week.

Lakhan Bhanwar, a labour inspector in Barwani district who recorded statements of the 57 rescued labourers, said that each of them testified of having been ill-treated and held hostage without being paid adequate remuneration. “They were made to work for close to 15 hours on a daily basis,” Bhanwar said, and “paid barely any money”. But when the labourers were rescued in Belagavi, the district administration there did not issue certificates declaring them as rescued bonded labourers.

This, Bhanwar says, nullifies all his work. “The district administration of the place where the labourers are rescued ought to issue a certificate so that the labourers can avail the state’s welfare scheme for rehabilitation and employment. But in almost all cases, these certificates are denied,” he points out. Bhanwar says the district administration is more focussed on proving they are free of bonded labour practice than rehabilitating the affected ones.

On completion of his examination last week, Bhanwar has written to Belagavi administration seeking their response and also initiation of the process under the BLSA Act. He is yet to get any response. It is also important to note that a certain exploitation is acknowledged as “bonded labour work” in one district and in the neighbouring district of Khargone, the administration is busy denying it.

Meanwhile, JADS and other rights organisations in Maharashtra and Karnataka are coordinating to rescue another 250 labourers stuck at different places. In Maharashtra, the workers are being rescued in Kolhapur, Pune and Satara. Among the victims of Satara, one woman has complained of repeated sexual assault by the contractors and the farm owners.

In Karnataka, rescue work is underway in Belagavi and Bagalkot. In Belagavi, some 26 persons – including very young children – are currently being sheltered by an NGO Spandana until the district administration takes over. “Along with the adults, at least nine children were working here as child labourers,” confirmed V. Susheela, the founder of Spandana. Susheela, along with JADS and other NGOs in Maharashtra, has been busy negotiating with the district administration, pursing them to file a criminal complaint, taking care of the rescued labourers and also arranging for their transport back home.

Also read: How Punjab’s Rural Women, Neck-Deep in Debt, Are Trapped in Microloan Cycles

Lack of action

Last week, Shivrajsingh Verma, the Barwani district collector, sent out two letters to Kolhapur and Bagalkot district administration to intervene in the matter. In the letters he has urged the administration to rescue the labourers in captivity and initiate appropriate criminal action under the BLSS Act. Verma says he has not heard from the collector’s office yet. Verma, unlike Bhanwar, says the situation in which the labourers were found don’t necessarily fit in the “strict definition” of bonded labourers. “They are exploited, yes. They have been bullied and made to work in inhuman conditions, yes. But it is difficult to strictly call this situation of bonded labour,” he claims.

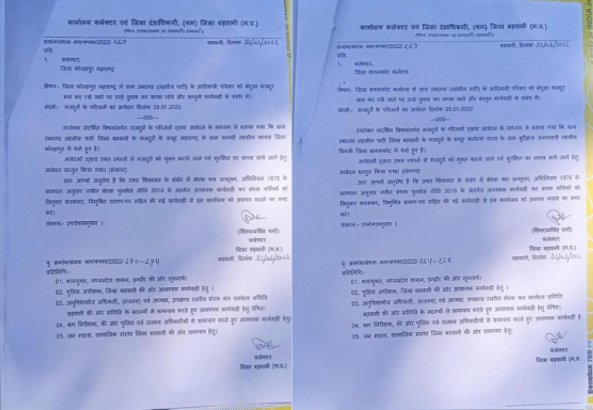

These two are letters sent by the Barwa collector to his counterparts in Kolhapur and Bagalkhot asking to help rescue the labourers trapped in their districts. Photo: By special arrangement

Madhuri doesn’t agree. The modus operandi, she says, is the same across the peninsular region of India. “An advance payment is made, which serves to act as a “bonded debt”. And as defined under section 2 (g) of the Act, the labourer hence enters into system of “forced or partly forced labour, and as a debtor, is presumed to render labour either without wages or for nominal wages, forfeit the right to move freely among other prohibitions,” Madhuri explained.

Most sugarcane factories across India’s western region are owned and run by big businessmen and influential politicians. They hire several thekedars or contractors to get labourers to work in the sugarcane farm. For instance, the gangs from Belagavi worked for Nirani sugars, whose chairperson and managing director is Vijay Nirani, son of BJP leader and Karnataka mines and geology minister Murugesh Nirani. Vijay, in an interview to The Hindu newspaper, has claimed that he was unaware of the incident. He further added that the contractors have been blacklisted.

Nitin, who works with JADS, explains the violation is multipronged. “They are bonded labourers, who are denied minimum work wage, made to work in inhuman conditions, battered and exploited. Each of these criminal acts are covered under separate legislations, but seldom get applied,” he pointed out.

Nitin feels unless the factory owners are held responsible, this vicious cycle is difficult to break. As migrants from another state, he reminds, the labourers are protected under the Inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act. The Act requires proper licensing of contractors, registration of workers in both states, payment of minimum wages and workers to be provided with basic amenities and a passbook recording of work and wages. “You see them all being flouted at every stage. And this happens only because the district and state administration doesn’t regulate the sector,” he says.

Note: Some names have been changed to protect the identities of victims of sexual assault.