Ahead of the Lok Sabha election, the crisis of unemployment unites India as few things do. Why are important sections of India out of work? How do unemployed Indians live? Why is the work available not enough to earn a livelihood? How do Indians secure employment? How long is the wait? With India out of work, The Wire unveils a series that explores one of the most important poll issues of our time.

In the picturesque landscapes of Dal Lake in Srinagar, a small community silently grapples with the intricate interplay of environmental degradation, urbanisation and the changing nature of their relationship with their ancestral livelihood.

Anthropogenic (human-induced) environmental degradation has been on the agenda of humanity for a long time now, however, even the most beautiful and popular tourist destinations – which one might assume are the most protected – in the world seem to be choking by the surge of plastic and pollution.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty. Photo: Intifada P. Basheer and Azam Abbas

The Dal Lake, named the “Jewel in the crown of Kashmir” by the Jammu and Kashmir state, is drowning in municipal sewage, and pollution, covered with weeds and patches of garbage.

The Hanji people (those living in houseboats) bear the brunt of the lake’s rapid urbanisation. Thanks to the rapid commercialisation of the surrounding region, they’re not just paying through their wages and house, but also through their self.

The unravelling causes of Dal’s pollution

“The Dal had a lot of fish. But this sewage has destroyed the fish. All the garbage goes into the Dal. We used to drink this water, but today you can’t even wash your face with it,” says Javed Ahmed, a fisherman who was relocated to the fisherman colony in Habbak, an area in the vicinity of the Dal Lake.

The issue of sewage and pollution in the Dal has been a well-documented phenomenon for a few years now.

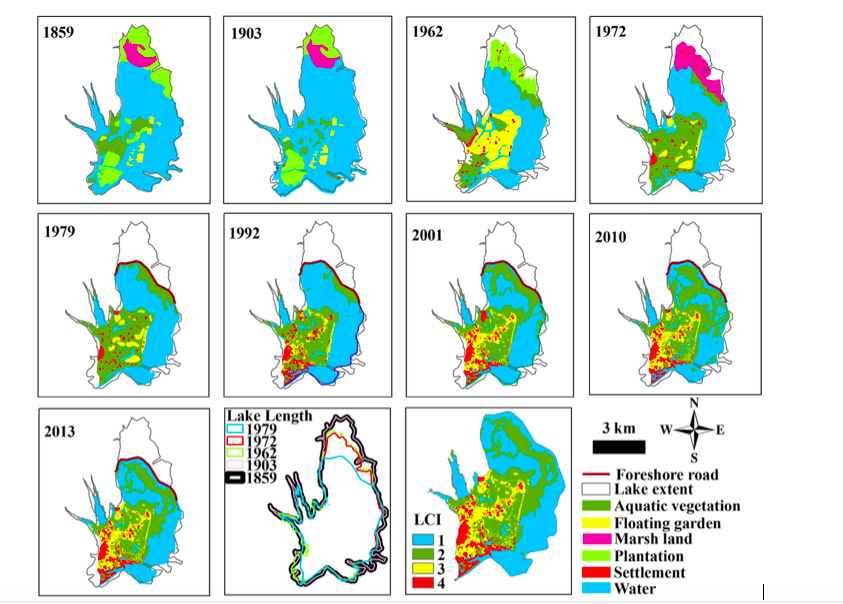

Academic and scientific work has been uncovering the causes of pollution and its permanent impacts. Noteworthy transformations occurred in the land use and land cover (LULC) within the lake between 1859 and 2013, as well as in the surrounding areas from 1962 to 2013.

An analysis of the demographic data indicates that the human population within the lake has surpassed double the national growth rate. These changes in both LULC and demographics have had adverse effects on the pollution status of the previously pristine lake.

While Javed blames the smart city projects launched in 2019, as well as the influx of tourism which choked their spaces – the sewage has been polluting Dal for a long time.

The region’s accelerated development has led to a decline in the fishing trade and displacement of people from their ancestral properties. This change is fuelled by the constant need for beautification of places like the Boulevard and the foreshore road- in which, it seems, the Hanji people simply do not fit.

The recent widening of the foreshore road along the Dal, under the Smart City Project, has made it difficult for the members of Hanji community to put stalls of barbeque or selling of vegetables on roadside This has disrupted the livelihoods and ancestral fishing practices of many among the Hanji people.

According to a Right to Information filed by Tariq Ahmed (a houseboat owner) in 2017, “Forty-four million litres (11 million gallons) of sewage was released into the lake from the city each day. In addition, about 1 million litres (260,000 gallons) of sewage came from houseboats.”

The dominant narrative has been that the houseboats pollute the Dal, however, the findings showcase otherwise. The photographs taken by environmentalists and journalists highlight the extent of eutrophication.

Photo: Land use land cover within the Dal lake from 1859 to 2013.

The present condition of the Dal is the result of a complex mesh of activities happening throughout the past few decades, as the surge of residents and tourists has grown exponentially. The findings from the interviews of Hanji people are in congruence with what the research and the local reporting have been suggesting that sewage dumping, population rise and mismanagement is causing irreversible damage to the Dal.

While the beautification of Dal is thriving – with proper roads, footpaths, and new shops opening to cater to the growing population of tourists – the lake itself is slowly dying, and with that, the Hanji community is also slowly being removed from their ancestral fishing grounds.

Loss of biodiversity

Mapping the impacts of the pollution happening at Dal is a mammoth effort which scientists have been carrying for a few years now, however, the Hanji people have been experiencing these impacts even before the issue became mainstream. Fishermen who have been living inside the Dal for decades have mentioned how the fish count in Dal has gone down exponentially, and the native species have almost disappeared.

An old fisherman who has been living in the Dal for decades says, “The fish in the Dal are small. Because of the sewage, the fish have declined. This sewage affects the seeds of the fish. We used to cultivate lotus stem (Nadru) but that is also declining now [The LCMA is using machines to clear the nadru growth in the Dal]. The floods had a devastating effect on the fish.”

Azmat, another fisherman working in the Tailbal region of the lake says, “The fish here used to be plenty, but now they’ve depleted significantly. We are left with little to no work. We face a lot of hardships because of this.”

The Hanji people used to rely on the local ecosystem which included various flora and fauna, which were also part of their diet. The eutrophication of the lake paired with reduced water quality has made the water unfit for anything, while the local authorities had installed Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) to mitigate the inflow of toxic sewage, recent reports show their tragic state.

“It has been reported that about 70% of the sewage generated in Srinagar City finds its way into the Lake. Three STPs are functioning under the control of LAWDA. These are heavily over-utilised and under-maintained,” the committee of experts (CoE) – appointed by the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir – said in its latest report, according to GNS.

The STPs were supposed to be renovated soon, however, the latest Red Algae bloom, dubbed a “natural phenomenon” by government officials, seems to show no sign of change after two years of said ‘renovation’.

According to a report carried by a daily newspaper Greater Kashmir in March, 2023, the government of Jammu and Kashmir had spent Rs 759 crore for cleaning of the Dal from 2002 to 2018 and the UT administration has spent Rs 239 crores from 2019-2023.

Even after spending so much on the cleaning of the Dal, the Hanjis do not see themselves as the part of the process except that they are employed by the LCMA department occasionally to manually clean the Dal.

It would have been beneficial if the government would have taken into consideration the knowledge of the elder generation of the fishing community living in the Dal by involving them.

Economic impacts of environmental degradation and urbanisation

The disappearing flora and fauna do not just create shifts in the local ecosystem but they also impact those who are dependent on the ecosystem itself for their livelihoods.

The destruction of fish has been devastating for the Hanji people economically. It is impacting their business and leading many of them towards losses and throwing them deeper into poverty. Since the Hanji community is a fishing community, their main source of income is selling fish and vegetables which grow out of the lake.

As explained by Azmat: “The inflation has risen. Prices of commodities keep rising. We don’t earn that much. We have to buy fish from outside, and if it gets spoilt, it’s on us.”

What Azmat talks about here is a real problem which is becoming commonplace. The ecosystem of the lake is destroyed, wherein no cultivation of any flora, or no breeding of any fish through seeds is possible.

This is pushing Hanji people to buy fish from fish farms and other states and sell it at a loss. This economic loss is putting immense pressure on their livelihoods and causing them to move away from the field of work altogether.

The economic issues are also exacerbated because of the lack of support from the local authorities and the government. While only one interviewee mentioned that businesses were hit post Article 370 implementation, the criticism of the government bodies was a recurring theme in the discourse.

Most people possess a fear of officials and hence were paranoid of researchers asking any questions, including on their daily lives or livelihoods. “The police come and destroy our fishes, throw them in water. In Lal Chowk, police throw them in Jhelum and we face loses,” says Ghulam Nabi, a 52-year-old fisherman.

Another major issue which almost all the interviewees talked about was the lack of a proper market to sell their produce. Many of them sit on the foothpath near the road and sell fish, and they’re told to move frequently because they disturb the ‘aesthetic’ of the newly constructed roads.

Jana, a 60-year-old woman who sells fish near the Dargah Hazratbal said that she has to pay rent to sit on the road and set up her stall, and the biggest problem she faces is the constant relocation to new locations as she has to carry all her belongings.

Ghulam Mohammad, who sells fish on the foreshore road says, “The municipality, they take all our stuff. I have kept my shikara [boat] here, I put all my stuff in that and leave. They even take tubs with fish in it. A lot of people used to sell fish on the other side but after they made the pathway along the road they had to shift. Our trade is based on water, we had asked them to at least make a stairwell along the road so that we may get some water, but they did not.”

This kind of subjugation from authorities puts immense pressure on the people of the Hanji community because most of them are struggling already to make ends meet as the sales of fish are almost always in losses.

The authorities seem to believe that removing Hanji people from the area and relocating them to a new location will somehow improve the condition of the lake itself, but even after multiple attempts, the issue remains.

Considering the huge sums being spent on the Save Dal Project, clearly, there is a deeper issue that the authorities are failing to understand, and the findings showcase how they might have been pushing away the solution all this time.

Role of the Hanji people in maintaining the ecosystem

“The government wants to beautify the Dal, so they relocated us but they are not able to keep it clean. We used to keep it clean,” says Azmat, who emphasises on the role of the community in maintaining the Dal as well as keeping it in an equilibrium. The overall process of urbanisation and removal of Hanji people has led to significant changes in the lake.

While the government might be removing the Hanji people from the areas for ‘aesthetic’ reasons, it is having a counter effect because the lake’s condition was also a result of the care and practice which went into maintaining such a fragile ecosystem. The Hanji people had been a big part of that.

For instance, the prevalent use of lamba zaal or longer nets, which kill the seed-laying fish, and stop the fishes from procreating. The Hanji people used the goal zaal or the round net, which requires skill to use; the entry of non-Hanji fishermen and the use of the lamba zaal by them has been reducing the fish count further.

The Hanji people, then, seem to be eager to help maintain the lake but have been denied any chance in the first place.

Another person asserted that the trade would have been different had there been a Mahigir person (fisherman) in the fisheries department, he adds,“A Mahigir knows these waters by heart. He knows how to keep this clean. How to catch fish. How to use the net. Thus, they would have prevented the illegal fishing activities in the lake. The net destroys the seed. It has been banned. The Mahigir has the know-how of the lake. At least, they would have provided the information to the concerned depts.”

This is an idea which is often referred to as the Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) framework employed in environmental projects, wherein the rural population is involved in the various processes of the project, so as to ensure true value to the beneficiaries.

There is an apparent lack of representation of Hanji people in the decision-making mechanism which leads to such watered-down efforts to help the community. The official engineer of the LCMA said, “The Dal is the responsibility of LCMA but unfortunately we have other departments interfering in our work. For example, we have been tasked to clean the Dal, now fisheries department has provided the license for cultivating nadru, we tried to remove that but due to media highlights we couldn’t. All the departments do as they wish. That is the reason for the sorry state of the Dal.”

This clearly shows the lack of coherence and clarity when it comes to organising a systematic approach towards reformation of the Dal, and the importance of hearing the people. These internal inefficiencies make apparent the need of a PRA-like framework, wherein the grassroots governance model can create a better way of handling sensitive ecosystems.

The physical and social erasure of identity

Over the years, the Hanji people have been removed from their homes, their ancestral livelihoods have been destroyed, and their trade has changed so drastically that not many of them would want their children to continue the trade. This kind of impact is not just the result of environmental issues, it is a result of a systemic subjugation of a particular community amid a blind race for development and growth to fulfil the needs of one section of society.

The Hanji community has already been relocated to different regions which has made it difficult for them to carry out their activities as usual. With this displacement, they’re not just losing money, but also a longstanding part of their identity and belongingness, which is fuelled by a misrepresentation of their role in the destruction of the lake and its ‘pollution’.

This new development is tainted with a sense of marginalisation, there is a visible difference in the house of the Hanji mohalla (locality) and non-Hanji mohalla, if one utilises a spatial lens, it becomes apparent how the spatiality of development plays a big part in erasing the identity of these communities which have been part of this space even longer than most authorities.

It must be understood that fishing is not only the livelihood of the Hanji community, it is also a part of their culture. So, the displacement of the members of this community means denial of cultural identity as well.

The cultural ramifications of rapid urbanisation

The halcyon days of the Dal Lake are slowly losing their charm, as the lake and its ancestral custodians of the Hanji community grapple with the repercussions of climate change amidst rapid urbanisation. Scientific findings and local narratives uncover the complex web of forces which has caused the decline of this once-pristine lake.

Weeds and algae growth on the interiors of the Dal Lake. Photo: Najam Us Saqib

The Hanji community and their traditional way of life are being impacted immensely as the unrelenting degradation of the lake continues despite the efforts by the state. The removal of the Hanji people under the guise of beautification efforts is shortsighted and overlooks their valuable traditional knowledge.

The erosion of their identity is a consequence which might be the most irreversible and tragic of all the losses. This process is emblematic of the larger problem we face when balancing rapid growth and change in society.

Acknowledging the inherent link between the Hanji people, Dal Lake, and sustainable development is vital. It emphasises the importance of inclusivity, community engagement, and preserving cultural identities to secure a harmonious and resilient future for this jewel in the crown of Kashmir.

Acknowledgment Note: The Visual Storyboard team of CNES would like to thank Dr. Khalid Wasim Hassan for his guidance with the fieldwork of the study. We also thank Ms. Maria Shawl, Mr. Zahid Sultan, and Ms. Bismah Yousuf for their help during the field work. Video essays from this field story are accessible from here

Deepanshu Mohan is Professor of Economics and Dean, Office of Interdisciplinary Studies and Director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES), O.P. Jindal Global University. He is a Visiting Professor with Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre at the London School of Economics and Political Science and an Honorary Research Fellow with Birkbeck College, University of London. Najam Us Saqib is a PhD Student and a Research Analyst with CNES Visual Storyboard Team. Ishfaq Wani is a PhD Student and a Research Analyst with CNES Visual Storyboard Team. Jayendra Singh is a Masters Student and a Research Assistant with CNES. Hima Trisha is a Law Student and a Senior Research Assistant with CNES. Video editing credits belong to Mr. Rajan Mishra.