Why I Can’t Find a Good Plumber: Exploring the ‘Skill India' Mess

I have Rati Bhan ji’s number on the speed dial, but reaching him is not so easy. He is one of the busiest men in north Delhi. He arrived with an apprentice and got to the bottom of why I wasn’t able to access water in my newly rented flat. Fighting through pigeons and a mini jungle with reptilian infestation on the terrace, he reached the overhead tank – which leaked. The solution: fit a new tank, a whole day’s job, after negotiating with the landlord.

I wasn't so lucky when I needed him for the second time. He was engaged with L&T on a contractual basis for an upcoming block of residential apartments in Noida. I was impressed, because a plumber who is no longer young but good at his work was in demand all over Delhi-NCR.

This made me realise why some aggregators have cashed in on the shortage of plumbers, electricians, carpenters, and masons in India.

We were supposed to get over this shortage, as well as the disdain for working class people, with Skill India, a flagship scheme that was launched in 2015.

It has a dismal placement record and absurdly short training programmes, where overzealous private players have replicated the public infrastructure of Industrial Training Institutes, instead of building upon it. This has happened despite the fact that the government think tank NITI Aayog had suggested ways to resuscitate it, as recently as January this year.

Why Skill India and PMKVY are inadequate

When I reached out to Rati Bhan ji again, it wasn't for a plumbing consultation. I wanted to discuss with him India's skill programmes. I wanted to understand why I can't find a good plumber when Rati Bhan ji is busy.

Rati Bhan ji, a plumber since 1996, says to be able to work on site, independently, a plumber needs five years of training mixed with experience. Photo provided by author.

He had returned from Singapore, triggering class arrogance in me. He was on training, funded by a pipe company that wanted to put him in charge of a project in Mumbai. The training was not part of the Skill India mission or Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana. This was not a wasteful two-month course for newbies, ill-suited to take the rough and tumble of plumbing, who will drop out of the trade in no time. Out of ten plumbers, less than two trained by Skill India stick around, practitioners who source from the mission told me.

The Singapore stint was training in best practices for Rati Bhan ji, who has been a plumber since 1996. He works on site with a team of senior and junior masons, and helpers, and labour. He is so experienced that he can detect, even from a description over the phone, where his team is getting stuck.

This kind of training is not provided in the Skill India syllabi.

The Indian Plumbing Association told me the correct way of training new plumbers: it should be a modular course consisting of at least eight modules, stretching over 15 days each. The modules should not be taught in continuity because plumbers, after all, have to earn between their training. The spaced-modules programme also lets the job market test out a plumber’s stickability.

Rati Bhan ji feels that while he can train an apprentice in a month to do plumbing of a basic bathroom, anything more will need a year. And to emerge as a plumber who can do “bade se bada kaam and chote se chota” or in other words, work on a site, will take five years of training mixed with experience.

Not sticking around

As against this, Skill India tries to prepare a plumber in two months.

Rohit Jadhav, who runs Swastik Plumbing and Home Services in Pune, said plumbing is a rough trade and new recruits simply give up and leave. Both Jadhav and Rati Bhan ji estimate that less than 20% of those entering the plumbing trade stick with it for the long term. India’s high and mounting heatwaves make it extremely difficult for a trade to be practised largely in the open. In addition, the Indian companies’ reluctance to provide basic equipment such as helmets and shoes to plumbers make it even more challenging.

“In the heat, a bathroom can become a furnace. This generation also wants to step out in ironed clothes,” Rati Bhan ji said, counting the various factors.

Even those who manage to adjust to the job, and prove themselves to be good at it, leave.

Jayashree Narode, a plumber, was featured on the Facebook page of Pratham Livelihoods, Skilling & Entrepreneurship – an arm of the Pratham Education Foundation – with the caption saying #WorldPlumbingDay.

“With a monthly salary of Rs 12,000, Jayashree can contribute to household income today,” said the FB page.

Narode got a job in Jadhav’s firm; he referred to her as a scrupulous and good plumber, particularly with women customers. “Women understand women better,” said Jadhav in Hindi.

She quit her job after getting married. This reporter was unable to track her down. The phone number that her employer has doesn’t ring, and Narode has no authentic presence on social media.

Jayashree Narode. Credit: Facebook/Pratham Livelihoods, Skilling & Entrepreneurship

Poor placements

The Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana, the more focussed programme of the umbrella Skill India mission, is awaiting its fourth phase. It is delayed because of a dismal placements record, reported Yogima Seth Sharma in The Economic Times in August.

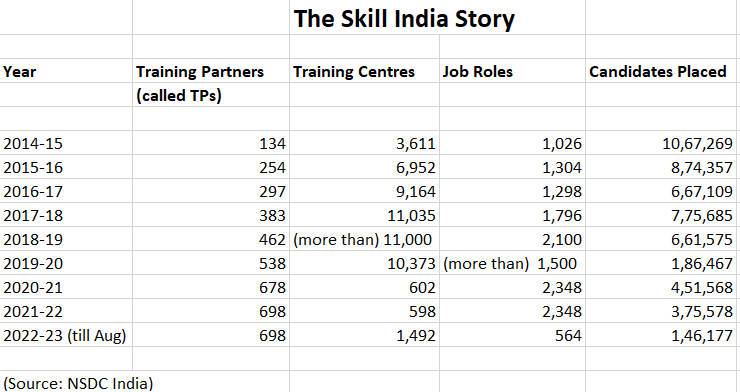

Launched from 2016 to 2020, the programme has sucked in Rs 12,000 crore. The National Skills Development Corporation (NSDC) signed on training partners to provide the training, giving them loans at 6% interest. Fifty of those training partners are defaulters, listed on the NSDC website, though the extent of their default does not find any mention on the portal. Job centres have declined, shows the NSDC site, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The prime ministerial programme’s placement record stands at 22%, which means out of 100 candidates only 22 are able to find jobs. Those who have spent years in skilling say all data around placements, whether from this programme or from the Industrial Training Institutes or ITIs, is inflated and misleading. This skew is related to India’s job market.

This programme managed to place 10 lakh only in the first year. When training centres were more than 11,000, they placed 6,61,575 candidates. So, one training centre placed less than 60 candidates in a year. It is not clear how many placements were apprenticeships which end in a year, leaving the Skill India graduate unemployed again. Apprentices can earn a decent salary in areas such as automobiles and Railways. Skilled workers will have to live with low salary, lack of benefits, and no injury compensation, if they become contracted labour preferred by most companies now. Skill India and PMKVY's training partners' names are sometimes common, and sometimes not. PMKVY is described as the flagship scheme of the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, implemented by NSDC.

Also read: Three Claims of Government Economists About Jobs Put to the Test

Apprenticeships and contracts

“I don’t consider apprenticeships as placements. Ek saal main mera baccha to vapas sarak pe aa gaya (my candidate is back to being unemployed in a year),” said Umesh Gautam, who, in roles as wide ranging as a placement officer or in-charge of a whole skill centre, has placed skilled candidates with companies for the past two decades.

Umesh Gautam, with two decades of experience in connecting skilled workers with companies, emphasizes that an apprenticeship should not be categorised as a job placement and should be excluded from placement data. Photo provided by author.

Apprenticeships which last a year is a carrot companies dangle in front of skilled candidates, he said. Once a year is over, apprentices are chucked out into the cold. Now comes the second carrot. Desperate skilled candidates see their earnings dip from Rs 25,000 a month to zero. They are directed towards labour contractors for India Inc. The riders: sub-contracted employment, no insurance, no graded pay hikes, no job security.

The "casualisation" of employment, or an increase in ‘on contract’ workers – and their insecure working conditions – led to the 2012 strike in Maruti, which resulted in the death of a manager. That strike itself was used to further hire workers on contract.

Also read: Why Is India Inc Reluctant to Participate in the Skill India Campaign?

Sanjay Srivastava, a sociologist, who is now at SOAS, University of London, but earlier taught at Jawaharlal Nehru University and visited the homes of some of the 147 jailed Maruti workers, had told me in 2015: “(We need) an industrial climate which is fair, which has long-term sustainability and some amount of stability.”

On a hot and humid afternoon in late September this year, I spoke to electrician Raj Kishore, who was replacing an old meter that had stopped giving the “meter reading” for Tata Power Delhi Distribution Limited.

This joint venture between Tata Power and the Delhi government, with the majority stake with the Tatas, supplies power to North and north-west Delhi, serving 1.9 million customers.

Kishore switched off the electricity supply of the building, lowered the visor of his helmet and started working.

He told me he graduated from an Industrial Training Institute or ITI in 2010, and earned Rs 20,000 a month.

He said he is employed through a contractor by the Tatas. The contractor deducts provident fund and Employee State Insurance, or ESI, which allows him to access certain government-run medical facilities.

Kishore said that any accident on the job, the likelihood of which is high in his line of work, will not be met with any monetary compensation. “The risk is all mine,” he said, before requesting that I do not talk to him while he is working.

The insurance that Kishore’s contractor, and others, subscribe to allows three days of accident leave where he can draw 90% of his daily wages – a pitiful amount. Any further assistance will involve a labour tribunal. Contractors cheating skilled workers by deducting the employer’s share of ESI also from the worker’s salary is not an uncommon story.

Raj Kishore adjusts his visor as he replaces a meter for Tata Power Delhi Dustribution Limited. He is employed by the company through a contractor. Contracted jobs are insecure and pay low wages with minimal benefits. Photo provided by author.

Kishore stays in a rented accommodation with his wife, children, and parents. “Guzara mushkil se hota hai (it is tough to make two ends meet),” he said.

An Indian Institute of Technology or IIT graduate of 2010 would, in contrast, earn a few crores annually.

Wages of skilled workers in India’s private sector remain so depressed, benefits so dismal and jobs so precarious, that it makes a majority hanker for government jobs. They sit for one exam after another, and demand accountability from a system which resists all these efforts.

The desire to have government jobs

Reeta Mahto, after graduating from a government-run ITI in Kanpur, completed her one-year apprenticeship in the Indian Railways in 2018-19. She earned a monthly stipend of Rs 5,800. The Indian Railways stopped absorbing apprentices automatically, which it used to do earlier. Apprentices need to sit for an exam – most probably to reduce the numbers. Mahto could not make the cut.

She was disappointed, and said apprentices are agitating all over the country to get jobs in the Railways.

Bhupendra Thakur, who graduated from an ITI as an electrician, is protesting too. He sat for an exam after graduating and enrolled in an additional course which allowed him to teach in ITIs, but the Rajasthan government is not filling vacancies. Thakur is part of the protests to pressurise the Gehlot government, which faces an election in a few months.

This desire for government jobs makes sensational front-page headlines in the shape of “lakhs apply for peon vacancy” but Indian media has never interrogated why people want these jobs.

“It is not surprising that so many people are queuing for regular government jobs. These are the only jobs that are not only reasonably well-paid but also secure. A regular government job means lifetime security (including pension) at a reasonably comfortable level, at least compared with most alternatives. No wonder these jobs are in such high demand. By extension, there is a high demand even for contractual government jobs, since a contractual job is always a potential springboard to a regular job,” said economist and activist Jean Dreze.

“I am not sure whether India is unique in this respect, but it is almost certainly unusual in the extent of the salary and pension gap between regular government jobs and the private sector, as well as in the extent of job security in the public sector,” said Dreze.

Skill India will not succeed as long as it fails to reign in Corporate India’s "casualisation", and their lack of will to pay a comfortable salary to its own workers.

An ignored report card and the transfer of an official

The skills programme has left out another gap: its backbone, the Industrial Training Institutes. Fifteen thousand ITIs, of which 22% are government-owned, form the public infrastructure of skills built with taxpayer money. This has been allowed to die. An excellent and in-depth NITI Aayog report in January 2023 laid out the symptoms and medicines for the comatose patient in 98 pages.

The report titled ‘Transforming Industrial Training Institutes’ actually had people visit ITIs, talk to working class enrolled in them, and even analyse their budgets.

It found seat occupancy in government ITIs at 57% higher than in private ITIs where only 43% of the seats, i.e., less than half, are occupied. Placements as well as work conditions of ITI graduates are areas of concern. “There is an annual public expenditure of about Rs 10,000 crore in running the ecosystem of 3,500 government ITIs, besides the Rs 2,200 crore STRIVE scheme,” said the report.

Kundan Kumar, an IAS officer and advisor for Skill Development and Employment vertical at NITI Aayog, who wrote the report’s preface, was transferred out, despite having an eight-year term at the think tank in 2021. When I tracked Kumar down to his new post in Bihar Bhawan, he refused to comment on the report, or anything else on this subject.

The reports, it seems, will languish in the Skill India bog.

Aparna Kalra is a Delhi School of Economics alumnus whose forte is investigations, profiles and data journalism. She has worked as a fact-checker on a Facebook project for AFP.

This article went live on October twentieth, two thousand twenty three, at zero minutes past one in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.