A Story About a Law Officer and the Violence in His Arguments

The proceedings before Supreme Court in the early period of the pandemic brought back memories of ADM Jabalpur – a case decided during the Emergency of 1975, in which the court, by a majority, conceded to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi the right to suspend even the right to life.

This decision was a black mark which has haunted the top court ever since. It has, since then, tried to unconvincingly bury the ghost of ADM Jabalpur “ten fathoms deep”.

The proceedings before the Supreme Court, as the lockdown was being relaxed, specially the jaw-dropping belligerence exhibited by a law officer, have resurrected the memories of another law officer who incidentally had the unenviable task of being the voice of the government in court during similar emergent times – Attorney General Niren De.

Who was Niren De? Why is this lawyer’s only legacy his provocative submissions before a Constitution Bench tasked to protect the Right to Life of the people?

Niren De served as Attorney General from November 1, 1968 to March 3, 1977 – almost the entire period of Indira Gandhi’s premiership before her fall to the rag-tag coalition put together by Jayaprakash Narayan. Before this, he had served as an Additional Solicitor General.

This was a period which witnessed a bitter custody battle for the constitution of India between the executive and the Supreme Court. Niren De weathered the turbulence and steered the ship as Captain Fali Nariman in his book Before Memory Fades: An Autobiography, recalls De’s “clipped English” and describes him as a man of “great stature and high principles”.

Also read: Journalists, Vultures and a Solicitor General

Michael Kirby in “HM Seervai: An Australian Appreciation” hints at how Niren De, having been the Attorney General who had lost Mrs Gandhi the Golak Nath, the Bank Nationalisation and the Privy Purses cases, was not exactly the favorite to lead the government’s side in Keshavananda where the Supreme Court would go on to lay down the “basic structure” doctrine.

This task would fall upon the legendary H.M. Seervai who accepted the brief only on the condition that he would open the case on behalf of the respondents. When the case was called out, there was “perceptible tension” between Niren De and Seervai as De believed that, as Attorney General, it was his right to lead the government’s defence.

Both occupied the first row seats. Niren De in the first chair with Seervai next to him, neither conversing. It seems that Nani Palkhivala and the other lawyers for the petitioners sensed the tension and even attempted to exploit the rift. Ultimately, Seervai complained to the law minister and threatened to walk out if the issue was not resolved.

Niren De lived on to continue to represent the Indira Gandhi government right upto the moment Internal Emergency was declared on June 25, 1975. However, the tensions had started long before. Fali Nariman (who was then on Niren De’s team as an Additional Solicitor General) recalls that three months before some person had dropped something which resembled a bomb into Chief Justice A.N. Ray’s motor car.

Though it turned out to be a dud, Niren De insisted that all the law officers get some security protection.

The build up to the ADM Jabalpur decision by the Supreme Court was the habeas corpus writs issued by various high courts directing the authoritarian Emergency regime to release political detenues. One such detainee in the Bangalore Central Jail was Lal Krishna Advani who, in his A Prisoner’s Scrap Book, recalls how Niren De had flown into Bangalore to oppose his petition. In fact, Advani notes how De tried to derail the case by producing fresh detention orders and taking the technical plea that his petition challenging the previous order had now been rendered infructuous.

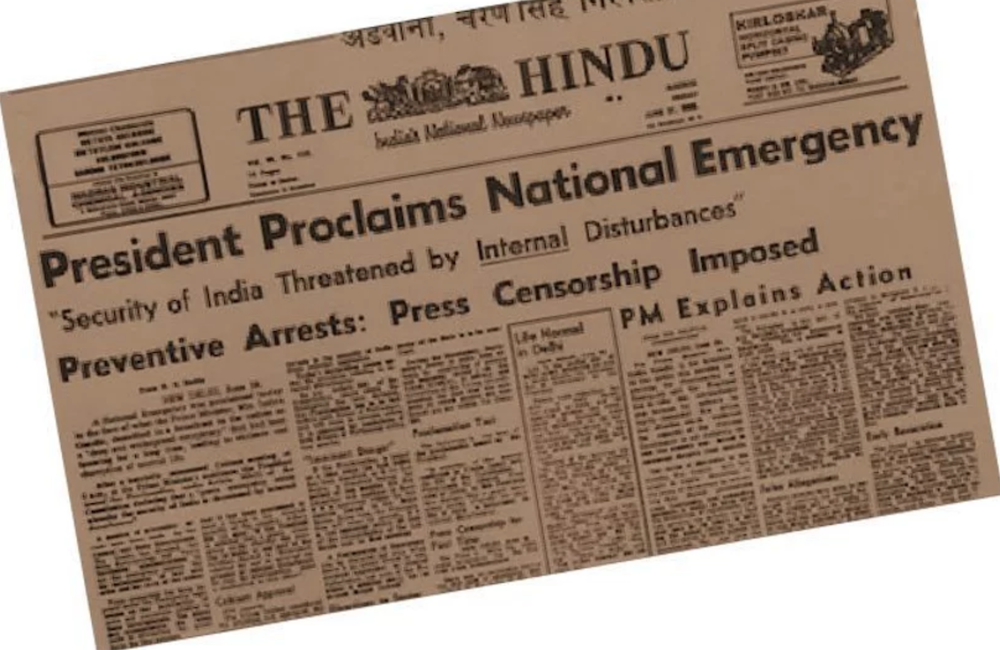

The Hindu's front page on the declaration of emergency. Source: polemicsnpedantics.com

Swapan Dasgupta in an article recalls how, at a function to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Emergency, the late Arun Jaitley revealed the details of an interesting conversation he had with Justice H.R. Khanna on a morning walk (I assume in Lodhi Gardens), the judge who penned the sole dissent in ADM Jabalpur Case and paid a heavy price for it.

It seems Niren De, who was the Attorney General for India presenting Indira’s case before court had confided in the dissenting justice that his “astonishing” submission to court – that during Emergency even the right to life was at the “mercy of the state” – was prompted by Khanna’s “leading question” from the Bench.

Khanna claimed that his now iconic question about whether during an Emergency even the right to life under Article 21 of the constitution could be suspended and that there could be no judicial remedy if a police officer killed a person out of personal enmity was aimed as much as at the Attorney as it was at his brother judges who sat “stony faced and expressionless”.

Surya Prakash in The Emergency: Heroes and Villains states that when Niren De responded with “Yes, there would be no judicial remedy”, those in the courtroom were stunned to hear such a submission.

Justice Krishna Iyer, one of the most distinguished justices to have adorned the top court, has extensively written and spoken about his interaction with Niren De on this famous court room exchange. He claimed that Niren De had, after the Emergency, confided in him that he had taken such an extreme position as he wanted to provoke the judges hoping to shock and rouse the judges “to rage against that violent view”.

Quoting from Iyer’s Leaves from My Personal Life, Mukesh Jagtiani recalls the exact exchange:

Khanna J: “Life is also mentioned in Article 21 and would government argument extend to it also?”

De: ”Even if life was taken away illegally, courts are helpless”.

Granville Austin in Working a Democratic Constitution, gives his version of the now infamous courtroom exchange:

Khanna J: “Supposing some policeman for reasons of enmity, not of state, kills someone, would there not be a remedy?”

De: “Consistent with my position, My Lord, not so long as the Emergency lasts. It shocks my conscience, it may shock yours, but there is no remedy.”

As we know from the New York Times report by William Borders, as 14 ceiling fans “whirred overhead” the majority of the ADM Jabalpur Court read out the decision accepting Niren De’s arguments. He had won the case and also a place in history’s hall of shame.

Krishna Iyer termed De’s submissions as “unconscionable” by democratic standards, proceeding in his iconic way to describe ADM Jabalpur verdict thus:

“Alas, the darkest hour of forensic downfall, except for the historic dissent of Justice Khanna, was when this disastrous jurisprudence marred our law reports.”

Iyer claims that at a dinner shortly after Emergency, De found him and unburdened himself.

He told Iyer that he was a “socially sensitive judge” and that he could appreciate how he had “sleepless nights” about his defence of the Emergency. He claimed that he had “thought of the strategy of shocking the judges into sanity, into rousing their revulsion, into reading down the deadly law, into claiming space for judicial invigilation as haven of human rights. So I urged the damned extreme position hoping that humanist jurisprudence would be the indignant robed reaction. I wanted the robes to rage against that violent view I propounded and come down on such Emergency inhumanity.”

Those aware of Krishna Iyer’s unmistakable language would well guess that De’s words sound more like Iyer than De, however one gets the essence of this contrition laden confession by a law officer who perhaps was grappling with the realisation that it was his “violent view” which was going to define his legacy for the history books.

Niren De passed away soon after this dinner confession.

Krishna Iyer, contrasting the principled resignation of Additional Solicitor General Fali S. Nariman a day after Emergency was declared to not only Niren’s retention of his constitutional office but also his submission of his “violent views” to the Court, has only compassion and understanding for the lawyer. He said, “Good men, gripped by grave crises, sometimes cave in, may be.”

Granville Austin also seems to weigh in favour of De saying that his arguing “by reductio ad absurdum, may have been purposeful”. He accepts that there was “credible speculation” by Justice Khanna and others that De by his provocative argument was making “an attempt to lose the case because he abhorred the Emergency’s harshness.”

Austin hints that, in fact, De was indeed brave as he feared that he and his foreign born wife would be harassed if the government coterie became aware about his reservations about the Emergency. According to Austin, De’s friends had noticed his tension and heavy smoking.

Niren De’s legacy sadly remains his provocative self-confessed “violent views”. Was he being bravely audacious in playing a fifth columnist and trying to tank the mighty Indira Gandhi’s regime from inside by deliberately making provocative submissions, as he later claimed, only to be frustrated by the cowardice of the Justices?

We will never know.

What I did find out from my secret source, someone from the same court as Niren De, was that he was called “Night and Day”.

Charles Dickens had said “If there were no bad people there would be no good lawyers”. This is where a law officer stands out from an ordinary lawyer called upon to defend “bad people”.

He defends the state. The state, by definition, is always good, always ‘day’!

Sanjoy Ghose is a labour lawyer in Delhi.

This article went live on June first, two thousand twenty, at thirty-four minutes past eight in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.