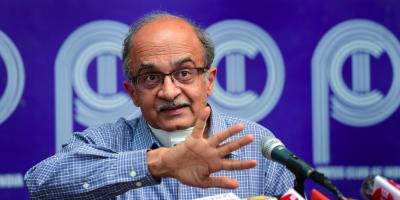

New Delhi: Prashant Bhushan on Monday paid the Re 1 fine imposed by the Supreme Court as a result of his conviction and sentence in the suo motu contempt case. He reiterated to the media his view that his payment of the fine does not mean he admits his guilt as a contemnor.

In his review petition filed on Monday, Bhushan contends that the contempt proceedings against him should not have been heard by a bench which included Justice Arun Mishra (since retired). He has recalled a few episodes which, he said, ‘strengthens’ Justice Mishra’s bias against him.

Instances of bias

First, on December 16, 2016, when Justice Mishra sat with Justice J.S. Khehar to hear the plea seeking a probe into the Sahara diaries case, Bhushan requested Justice Khehar to adjourn the matter because the allegations pertained to the bribing of Prime Minister Narendra Modi when he was the chief minister of Gujarat. As the PM was expected to clear Justice Khehar’s appointment as the next chief justice of India after the then CJI retired on January 3, 2017, Bhushan said there would be a conflict of interest at that point of time in his hearing the case. Justice Mishra then orally alleged that this very plea amounted to contempt of court.

Second, Bhushan has claimed that after Justice Mishra heard and dismissed the application filed by Common Cause seeking a court-monitored probe into the Sahara pay-off case on January 11, 2017, he tweeted the fact that the then chief minister of Madhya Pradesh, Shivraj Singh Chouhan, attended the reception of Justice Arun Mishra’s nephew, as published in local newspapers. The tweet also carried the photo of Chouhan greeting the newly married couple at the residence of Justice Mishra. As Chouhan was one of the alleged recipients of a Rs 10 crore bribe by the Sahara group, Bhushan’s inference was that Justice Mishra entertained a grudge against him for exposing this ‘unholy nexus’.

Also Read: How Justice Arun Mishra Rose to Become the Most Influential Judge in the Supreme Court

Third, Bhushan recalled the proceedings in the Supreme Court on November 10, 2017, when a five-judge bench including Justice Arun Mishra was hearing a petition by the Campaign for Judicial Accountability and Reforms (CJAR) seeking a court-monitored probe into a first information report (FIR) filed by the CBI regarding alleged planning and preparation for procuring favourable orders in the Prasad Medical Trust case. When Bhushan sought the recusal of the then chief justice, Dipak Misra, from hearing the case, since he had heard the Prasad Medical Trust case earlier, Justice Mishra again observed that such a plea amounted to contempt of court.

On November 13, 2017, when Justices R.K. Agarwal, A.M. Khanwilkar and Mishra heard Kamini Jaiswal’s petition on the same matter, Bhushan asked Justice Khanwilkar to recuse from hearing the case because he was also part of the bench along with the Chief Justice Dipak Misra which dealt with the medical college case. The judgment of the bench in this case termed Bhushan’s request as amounting to contempt of court and imposed a Rs 25 lakh fine on the CJAR, of which Bhushan is the convenor.

Prashant Bhushan (left), Justice Arun Mishra (right), and in the background, the Supreme Court of India. Photos: PTI

In Attorney General for India v Prashant Bhushan, Bhushan’s tweet about the AG allegedly misleading the Supreme Court about the meeting of the High Powered Selection Committee to select the CBI’s interim director led to a controversy. The AG, K.K. Venugopal denied the insinuation and submitted the minutes of the meeting to show that the three-member committee had indeed agreed to appoint M. Nageswara Rao as the interim director, after the then director had to quit, following the government’s decision to replace him. Bhushan expressed his regret over the tweet, and the AG sought the closure of the contempt petition against him. But Justice Mishra kept the proceedings alive by insisting on laying down guidelines on whether lawyers can tweet on pending cases.

In this case, Bhushan raised the issue about the propriety of filing of a contempt petition in the garb of an Interlocutory Application in a pending matter, and thereafter the same having been mentioned and listed as the contempt petitions 1 and 2 of 2019 before the bench of Justices Arun Mishra and Navin Sinha on February 6, 2019. This was one of the few pending cases which Justice Mishra did not conclude hearing.

In the same case, Justice Mishra asked Bhushan to tender an unconditional apology for moving the recusal application, which Bhushan had refused. Justice Mishra on March 7, 2019 made it clear that there was no reason for recusal (without reading Bhushan’s application for recusal) and that he would deal with it. He also stated that the effect of filing the recusal application would be considered at the next hearing. According to Bhushan, the manner in which Justice Mishra insisted on hearing the contempt petition despite the AG’s withdrawal of his plea, and his taking exception to the filing of the recusal application itself, raised serious apprehension of the judge’s bias against him.

Bhushan pointed out that his letter to the CJI on July 26, 2019 brought these issues to his notice, and also explained why he could not file a recusal application before Justice Mishra himself, as it would have invited a similar response that the application itself was contempt.

Bhushan has claimed that the CJI’s non-response to his letter is a ground for rehearing the entire contempt proceedings afresh by a new bench, as Justice Mishra has now retired.

Also Read: The Prashant Bhushan Contempt Case is About Power and Politics, Not Law

Flaws in August 14 judgment

According to Bhushan, the finding in Paragraph 18 of the contempt judgment of August 14 that the “power of this court to initiate contempt is not in any manner limited by the provisions of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971” is an error of law apparent on the face of the record, a legitimate ground for review.

Bhushan has emphasised that a proceeding of criminal contempt, which is initiated suo motu, must apply all procedural safeguards of the 1971 Act and the 1975 Rules (framed to enforce the Act) as the court is both the party that is aggrieved and is also the judge acting in its own cause.

Bhushan has also doubted the legal basis of the Arun Mishra bench’s claim that it had followed the procedure as prescribed in the judgment of P.N.Duda v P. Shiv Shankar, while taking suo motu notice of contempt, without the consent of the AG. Bhushan has clarified that in the P.N.Duda v P. Shiv Shankar judgment, which was delivered by two Judges, there was a disagreement between them on the maintainability of the petition without the permission of the AG, and the procedure to be followed in such cases. Justice Ranganathan, in his separate opinion, found Duda’s petition not maintainable either as suo motu petition or otherwise.

Bhushan, therefore, has claimed his grievance that he was not supplied with the copy of the petition, on the basis of which the court had initiated suo motu proceedings against him. The petition, filed by Mahek Maheswari, sought exemption from filing prior permission of the AG. Bhushan, therefore, argues that entertaining such a petition as a suo motu petition is another error apparent.

Supreme Court. Photo: PTI

Bhushan has contended that the notice issued to him for his second tweet of June 27 (in which he said future historians will note the role played by the last four CJIs in the ‘destruction of democracy’ in the country) was not a result of proper procedure on the administrative side, as mandated by the judgment of Justice Ranganathan in the P.N.Duda case. The bench could not have taken suo motu notice of the second tweet directly on the judicial side, without the registry bringing it to its notice on the administrative side. As there is no administrative order placing it on the judicial side, the entire proceedings in respect of the second tweet of Bhushan including the August 14 judgment is an error apparent on the face of the record, Bhushan points out with considerable force.

Bhushan has also argued that the bench’s failure to hear the AG – despite his presence during the hearing on August 5 – before delivering the conviction judgment on August 14 was a serious flaw, as the AG is the “only independent mind that can throw light on if there is any contempt at all, the court being the aggrieved party as also the adjudicator”. As a result, the finding in Paragraph 18 of the August 14 judgment that “it is equally well settled that once the court takes cognizance the matter is purely between the court and the contemnor” is an error of law apparent on the face of the record, Bhushan contends.

Bhushan has submitted that it is necessary to place before the court further evidence regarding the comparative number of cases being heard and decided by the Supreme Court during normal, pre-COVID-19 functioning and its functioning during the lockdown mode. The court’s non-consideration of his plea is a cause of serious prejudice to him, he has said.

Bhushan’s first tweet deplored the fact that the court’s limited functioning due to COVID-19 had resulted in denial of the citizens’ right to access justice. The bench had argued that this was factually incorrect, but did not provide comparative data about the number of cases heard and decided before and after the lockdown started.