Asako Yuzuki's ‘Butter’ Is a Modern-Day Call for the Emancipation of Women

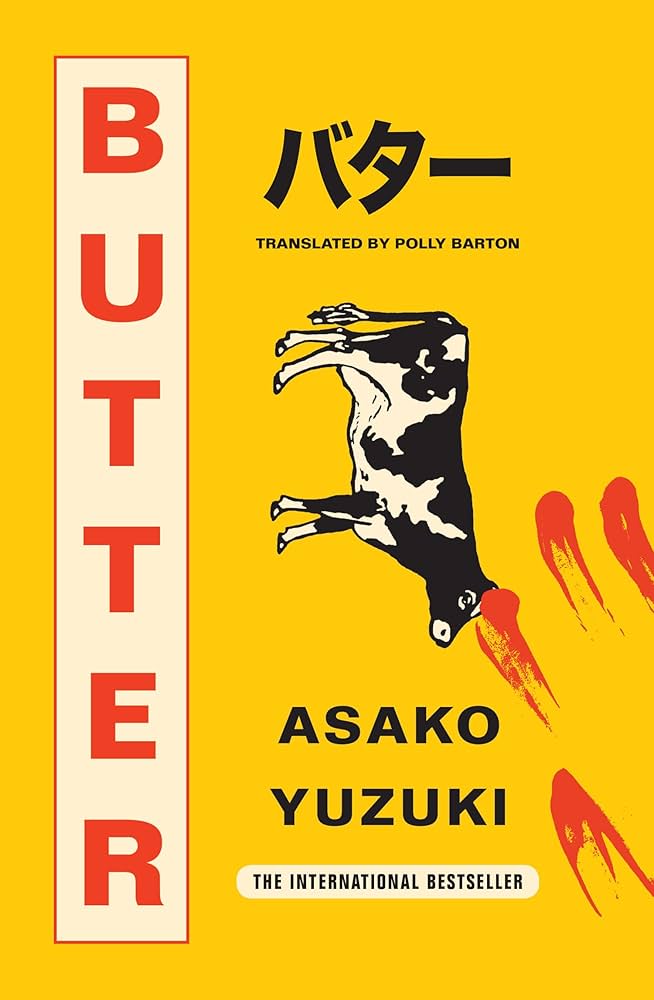

As I mooched around Edinburgh’s Princes Street Waterstones – like a living embodiment of some generic ‘dark academia’ Pinterest board – and first picked up Butter, I will admit that I did, in fact, judge the book by its cover. The lurid yellow stuck out, fittingly, like a knob of butter amid a sea of greying vegetable-y Penguin Classic stew, emanating an aura of quiet confidence. Or maybe that’s me idealising the potentially mundane act of book purchasing, conferring a weightier significance to something that in fact was nothing out of the ordinary. Well, to me, it was anything but – since it instigated the 48-hour tailspin that has dragged me from bed to mirror to journal to kettle to bed again, and finally to laptop. All this to say, I truly adored this book.

Butter somehow found me at an ideal point, and was the first stone in some existential avalanche, coalescing harmoniously with my other current art form fixations and real-world circumstances to deliver some message from the universe: Life doesn’t have to be this difficult.

We follow the interactions between journalist Rika and the infamous Manako Kajii, who has murdered three of her (rich and old) ex-lovers, after seducing them with delicious food and by embodying their fantastical imaginings of womanhood.

Asako Yuzuki, translated by Polly Barton

Butter

Fourth Estate, 2024

What struck me most is the paradox that lies at the core of the Kajii character. She transgresses and denounces the strictures of contemporary diet culture and our obsession with thinness, which to Yuzuki’s, and now my, mind is the true opiate of the masses (sorry, Karl). Yet simultaneously her only purported earthly loathings are margarine and feminists. Furthermore, she adheres to nearly every other norm of femininity, touting the importance of providing for men (nutritionally and sexually), and embracing their position as the superior sex.

It’s perhaps the incongruity of her progressiveness amidst all these archaic values that moved me so much. With an arcane nonchalance, Kajii denounces decades of exercise, ‘health’ and thinness propaganda, picking it up and flicking it away like a piece of lint on the woolly jumper of Japanese culture. I had never before heard of the impossibly high rules and standards of beauty being described as opt-outable.

Kajii’s character presents another way to live life, to narrator and reader alike. She enjoys and luxuriates in the warming embrace of good food and male attention, despite every orifice of her world denouncing this as unladylike and improper. She simply doesn't buy in to the rules that so unreservedly enslave our narrator, and consequently enjoys a mental liberty that transcends the confines of Tokyo Detention Centre. Indeed, we are left wondering whether her physical prison cell is any worse that those that have entrenched themselves into the female psyche.

Obviously, that’s not to say that it’s easy to simply ‘opt out’ of centuries of rules designed to secure female submission – let me tell you, if the modern-day woman is in a prison of their own design, I should change my Linkedin bio to 'Interior Designer' – nor does Kajii leverage her freedom in a wholly admirable manner (murder, for example). But it felt like a vestige of hope. Maybe perpetual submission and consequent misery isn’t unavoidable, if we don’t want it to be? Gaining a bit of weight doesn’t have to rattle the tectonic plates of our media-addled brains, and striving for some nebulous conception of success at the expense of actual joy need not be inevitable. It felt like this book, Kajii’s character in particular, came up and slapped me in the face, reminding me of my own agency.

It felt something like going to university for the first time and realising you don’t have to turn up to lectures if you don’t want to. Except in this case the fear is not that your anarchic existence could lead to failing your degree, but takes a far more visceral and gut-wrenching form that, maybe, you didn’t have to follow these rules all along. We accompany Rika as this realisation gradually washes over her and ebbs into every sordid crevice of her life. Her boyfriend, her late father, even other women project an idealised image of an obedient woman onto her and her choices, with any deviation being policed and reprimanded.

Food is such a powerful allegory for the suppression of women because it is something that women are supposed to be able to manipulate and contort into erotically succulent masterpieces, whilst also retaining ultimate control and restraint around it. It felt almost salacious and perverse to read a woman salivating over food so brazenly, enjoying a mound of steaming rice with salted butter and soy sauce deemed tantamount to a religious experience. Amidst the jungle of sensuous description, we find ourselves lost to experience, being guided by how we feel instead of what we decide.

It is made bitterly obvious that we have extracted the pleasure from work, from eating, from relationship dynamics, because they all supposedly serve some greater purpose of achievement. Striving for romantic, physical or financial success keeps us on an inexorable hamster wheel which has numbed our entirely-human sensations and capacities to be feeling-guided. This is illustrated so delicately and beautifully by the narrator’s best friend, Reiko, in her description of how people now require specific instructions in recipe books because ‘salt to taste’ or ‘good amount of seasoning’ is too vague. Somewhere along the line, in the drive towards mechanisation, we too became automated, as though metallic pools of molten titanium were poured clumsily into the pretty-pink folds of our brains, willing us to submit.

India Parmar is a student at Edinburgh University.

This article went live on March second, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.