‘Viksit Bharat’? Not If You Look at Low Allocations for Poor and Middle Classes

From a closer review of allocations, Union government’s focus on capital expenditure seems unchanged, as it has increased by 11.1% for FY25, in comparison to a 37.4% in the previous financial year. In the annual report, the Economic Survey cautions against geopolitical tensions induced fractures in the supply chain, shaking up economies globally.

The Indian economic landscape, as argued earlier, has braved this and has shown economic resilience in its capital and stock markets, as well as by maintaining inflation 1.4% below the global average. A steadying CapEx is a cause of worry for India’s social welfare spending outlays, as social sector spending has been on a continual decline for some critical programs, and in 2023 was well below 20% since 2009. It is clear that the Modi government wants its revenue expenditure priorities to move towards ‘jobs creation’ (from a package of new schemes announced) but even those are coming at the cost of other essential welfare-expenditure.

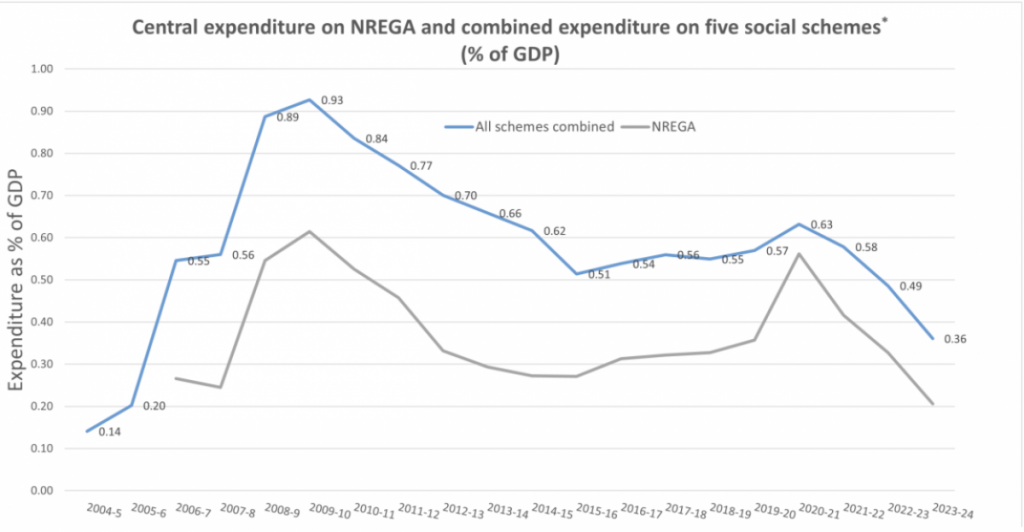

Evidently, NREGA (National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) along with other social welfare schemes like PMMVY (Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana), NSAP (National Social Assistance Programme), Mid-Day Meal programme and ICDS (Integrated Child Development Services) have witnessed a rapid decline since the 2019-20 Budget. PM’s Awas Yojana has seen larger allocations in a more positive push towards affordable housing (but the demand challenge in affordable, low income housing overrides any one scheme’s push to address this)

Source: Budget documents of various years. Graphic: Pranay Raj/The Wire

The estimated increase in allocation for the revenue expenditure and capital expenditure for the FY24-25 is 6.2% and 17.1% respectively.

The Union budget estimate for this financial year's revenue and capital expenditures are Rs 37,09,401 and Rs 11,11,111 crore (3.4% of the GDP) respectively. This increased growth in allocation to capital expenditure over revenue expenditure shows the government's higher focus on long-term infrastructure projects over the immediate needs of society, especially their social needs which are fulfilled through policy interventions and welfare schemes.

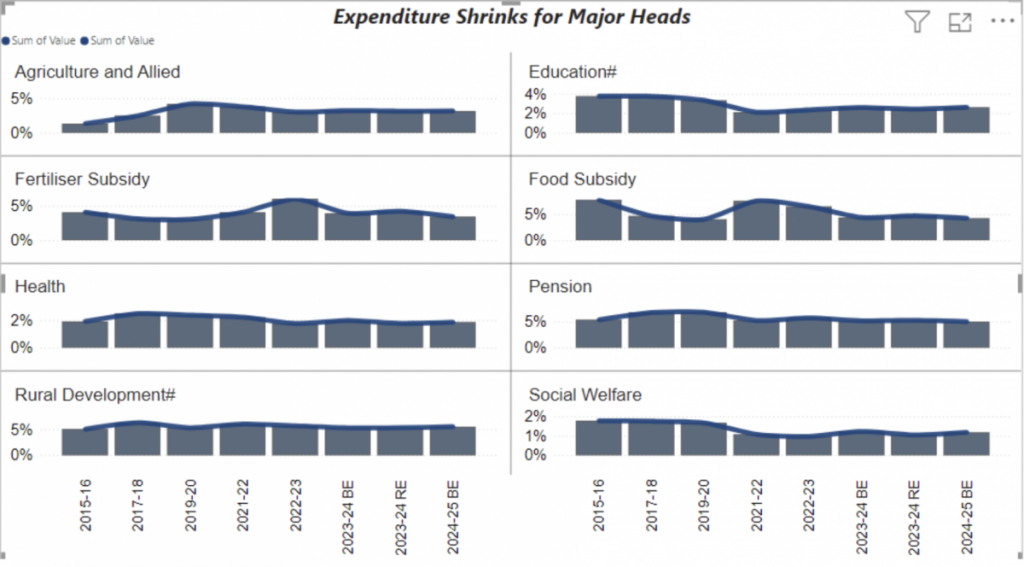

In this year’s Union Budget estimates, from a closer reading of the allocations assigned for the social sector such as health, education, one can see a clear decline or a continuance in the government’s status-quo approach in lesser prioritisation of health and education needs. Only the social welfare sector saw an increase from 1.04% in FY24 RE to 1.17% in FY25 BE (Rs 56,501 crore was allocated). The health sector has also shown a slight allocation increase of 13% compared to last year.

Despite the rhetorical push of the ‘Viksit Bharat’ agenda for developed India ahead, critical schemes addressing the poor and the middle class are not receiving the required allocation of funds in the 2024-25 Budget. Some schemes and the fund allocation this FY compared to the previous year are given below:

- MGNREGA, a scheme providing rural employment was allocated only Rs 86,000 crore same as in FY23 RE, there has not been a sufficient increase in the allocation to this scheme which is still in high demand within rural society.

- Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman (PM POSHAN) has shown a slight increase in the allocation from Rs 10,000 crore in FY2023-24 RE to 12,467 crore in FY2024-25 BE.

- The National Social Assistance Programme which includes the National Old Age Pension Scheme, the Indira Gandhi National Disability Pension Scheme, the National Family Benefit Scheme, etc. have been stagnant, 0.2% of the total expenditure.

- Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0 scheme for children under 5, pregnant and lactating women and adolescent girls, the allocation has increased slightly from Rs 20,544 crore in FY 2023-24 BE to Rs 21,200 crore in FY 2024-25 BE.

- Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN), is a scheme which aims to provide financial assistance to farmers’ families, the government maintained the Rs 60,000 crore allocation that was given in the FY 2023-24 BE and RE.

Outcome-based budgeting

Over the years, the budgeting system has continuously evolved, to ensure efficiency in allocation of resources and meeting developmental aims. The budgeting system has come a long way since 1969, when a performance-based system was introduced for the first time. Until 2017, outcome budgeting existed partially, until an Output-Outcome Monitoring Framework was implemented.

An outcome budget undergoes three main stages. The first stage is aimed at preparing detailed and procedural policy designs and frameworks for areas where policy interventions are required. The second stage involves implementing the policies by identifying stakeholders and ensuring the executing of policy interventions. The third stage is associated with assessment of performance and evaluating the improvements in the outcomes of stakeholders i.e. monitoring whether the scheme’s aims are being fulfilled.

A report by the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability shows that only 11 states and UTs are prescribed to the Outcome Budgeting System. From these states, over 90% of the departments in the states of Assam and Gujarat report to the Outcome Budgeting Statement, while states like Arunachal Pradesh and Jharkhand have the lowest percentages.

Odisha has instituted a new system called the Budget Execution Technique Automation, intending to standardise the process of outcome budgeting. Odisha’s positive efforts to institutionalise a proper mechanism to ensure output and outcome budgeting have resulted in a commendable performance on various schemes.

The data in the pages ahead showcase the state-wise performance of states’ on two selected social welfare schemes. Evidently, states like Arunachal Pradesh and Bihar have sub-par performance in terms of utilisation of allocated funds. This, in turn, can be attributed to their poor system of maintaining a check on the efficiency of implemented schemes, resulting from a budgeting system that does not utilise Outcome Budgeting. In comparison to states like Assam.

The data below shows the state-wise performance of these states on the NFSM (National Food Security Mission).

State-wise performance on the NFSM Scheme

Source: CNES-InfoSphere.

States like Assam and Chhattisgarh which have an Outcome Budgeting System, have utilised more funds due to continual evaluation and monitoring along all stages, as compared to states like Bihar and Arunachal Pradesh.

The gradual reduction in social sector allocation leaves less scope for states to adopt and implement the system of Outcome Budgeting Statements. To ensure proper utilisation of funds and in turn better social welfare and developmental performance in the fiscal years ahead, the government must work towards increasing the budgetary allocations for the Social Sector. Higher allocation would mean it is more closely affiliated to outcomes and more funds can be allocated to different stages in the OBS process.

Efforts to instate a system of performance evaluation and monitoring in place would then be more feasible and result in more promising deliverables which can then be seen in the form of improvements in the performance of policy intervention indicators.

Entitlement over empowerment?

The finance minister in the Union Budget, after years of apathetic neglect and macroeconomic policy indifference meted to critical government voices, implicitly acknowledged the nature of structural gaps observed in India’s ‘jobless growth’ trajectory, which has continuously observed a higher output-employment gap, and a weakening trend in macro-labor productivity levels. Still, a closer review of the budgetary fiscal math shows how the tokenistic approach to welfare, prioritising basic marginal entitlement without any focus on empowerment remains consistent with Modi Government’s fiscal strategy.

A lot of voices providing reflections on the budget while presenting the government’s view have defined this as a ‘pro-employment’ centred budget.

Also read: Budget 2024: A Lacklustre Response to India's Deepening Employment Crisis

As the government refocuses its strategy on skill development in the 2024-25 budget, several new initiatives are being introduced. Notably, a new scheme aims to equip 20 lakh young individuals with essential skills over the next five years. Additionally, the finance minister announced revisions to the model skilling loan scheme, increasing the loan amount to up to Rs 7.5 lakh.

Despite these increased investments in skill development programmes, significant challenges remain. A key concern is the persistent mismatch between the skills being taught and the actual demands of the job market. This misalignment between rising capital expenditure and insufficient social investment continues to impede efforts to effectively scale successful programmes and address critical skill gaps.

And, while the government's emphasis on skill development represents a rhetorically, positive shift, the actual, measurable effectiveness of these new initiatives may remain weak, and largely depend on overcoming ongoing challenges like high unemployment.

To truly bridge the skill gap and enhance employment prospects, a more cohesive approach towards functional literacy and competitive skilling is needed – one that aligns training programmes with job market needs, ensures sustainable funding, and integrates robust mechanisms for tracking progress and impact.

Addressing these issues, fiscally, and through greater private sector partnership for job/labor intensive sectors will be crucial for turning ambitious plans into tangible outcomes and fostering a workforce capable of meeting the demands of a modern economy.

This analysis of the fiscal math of the Union Budget 2024 has been put together by the CNES InfoSphere team as part of its Closer Look at the Union Budget series.

For details, see its website here.

This article went live on July twenty-ninth, two thousand twenty four, at fifty-four minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.