The Killing of Palestinian Journalists Constitutes One of Journalism’s Darkest Moments Historically

The ceasefire in Gaza has brought a tentative moment of pause; a time to add up the losses and count the dead. The figures are horrendous: over 46,000 dead, over 111,000 injured; over 14,500 children killed; countless bodies buried in the rubble.

Amidst the devastation, another figure rises: the killing of over 200 mediapersons. Never in the history of war coverage have so many journalists lost their lives, and in so short a span.

The conclusion is obvious and disturbing. It is all about felling the telling of the tale. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) have made killing journalists an important part of their military strategy. Even as Israel wages a highly sophisticated information war in parallel to its war in Palestine, it has also systematically attempted to blot out the Palestinian narrative and silence those attempting to report on the situation in Gaza and the West Bank.

The world got its first inkling of the master plan nearly a year and a half before the October 7, 2023 Hamas strike on Israel, when Al Jazeera correspondent Shireen Abu Akleh was shot by the IDF in the head while covering an Israeli raid on the Jenin refugee camp in May 2022.

The UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, under its chair Navi Pillay, recognised that Abu Akleh was yet another victim of the excessive and disproportionate force used by Israeli security forces and that “this was also an attack against journalists, who were all clearly identifiable, which is a recurring pattern identified by the Commission.”

It was possibly for the first time that attacks perpetrated by Israel on journalists in the region were acknowledged publicly as part of a “clearly identifiable” and “recurring pattern”.

The pattern reinstated itself immediately after Israel launched its military assault on Gaza Strip after October 7. A vice-like grip was kept on any footage emanating from Gaza and as early as on October 14, 2023, it was reported that IDF soldiers were ordering journalists to stop their filming and leave without delay.

By the end of 2023, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) was demanding that the crossing at the Rafah border between Gaza and Egypt should be opened so that journalists can come and go at will so that they can report on the situation without impediment. The organisation noted that Palestinian journalists are being imprisoned in the Gaza Strip, even while “foreign journalists are being denied access”, undermining the media’s ability to cover the conflict.

Jonathan Dagher, the head of the RSF’s Middle East desk, observed at that point:

“While the Israeli army continues to kill journalists in Gaza – 14 in the course of their work in less than two months – and to restrict their access to vital supplies and equipment, and while Israeli disinformation campaigns undermine the entire media’s credibility, the Israeli authorities still refuse to allow international journalists access. Journalists must be able to cover this war. Gaza must not become an information black hole. We call for the urgent opening of the Rafah crossing.”

Once the IDF had successfully ensured that all international journalists apart from those embedded in the Israeli army had vacated Gaza, its strategy to target journalists in Gaza began in right earnest.

Explained Yassir Abu Hin, one of the speakers at Tawasol 4, organised by the Palestine International Forum for Media & Communication in Istanbul earlier this month, which I attended:

“When European and American journalists were reporting from Gaza they were not killed. Many of them helped to further the Israeli narrative. When orders came to them from the Israeli authorities to leave Palestine, the majority did leave and Israel began their targeting and physical elimination of Palestinian journalists.”

The importance of keeping the Palestinian narrative alive, a point reiterated by Ilan Pappe, Israeli professor at the University of Exeter who spoke at the Tawasol 4 conference through video, is fundamental to any resistance to the settler colonialists brutally occupying the land.

“The importance of protecting the Palestinian narrative and disseminating it cannot be emphasised enough,” he remarked, pointing to the complicity and unacceptable indifference of the West to what is happening in Palestine.

The international media, if they had chosen to do so, could have kept covering the region during these brutal 15 months, but they did not. It was into this vacuum that local journalists, some of them students and academics, picked up their microphones and laptops and attempted to keep the narrative from Gaza going.

As Hin described it, “When the whole world had given up on Gaza, the people of Gaza stepped in to ensure that what was happening in Gaza did not remain undocumented.”

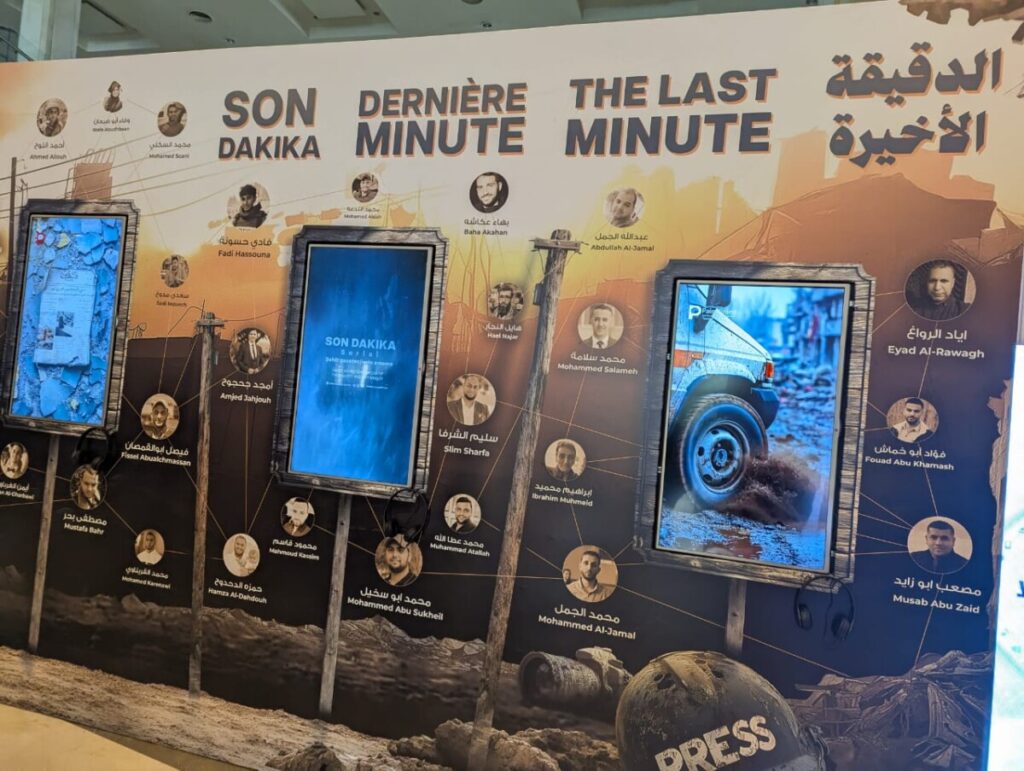

They were the first observers of the genocide and they paid the price for documenting it with their lives. The actual number of media workers killed by the IDF in Palestine varies, but a well-mounted, extremely poignant installation at the Tawasol 4 conference, ‘The Last Minute’, puts the figure at 209.

Another exhibit at ‘The Last Minute’ installation. Photo by author.

The installation attempted to bring these dead witnesses to life for viewers. According to Hana Almir, a graphic designer based in Lebanon who anchored the installation, the first task before her was to honour the murdered journalists of Gaza.

“It was difficult to arrive at a number and represent everyone who was killed. Many have been lost under the rubble, some were killed in their sleep, others while they were actually reporting on the ground. Some were bombed along with their families. So apart from carrying the names and faces of a hundred of them as a background to our installation, we focused on the stories of five men and five women, on whom we had the most information. We brought them to life through the use of AI and creative scripting, in order to capture their last minutes of life. We included Shireen Abu Akleh, who was killed earlier, in our narrative because she has become an icon for us.”

The ten men and women represented were Ismaeel Al Ghoul, Emine Hamid, Iman Al Shanti, Ayman Al Yedi, Duaa Sharaf, Refaat Al Areer, Samer Abu Daka, Shireen Abu Akleh, Mustafa Al Sawaf and Hiba Abadila.

Scripted in Arabic, English, French and Turkish, ‘The Last Minute’ had an immediate impact on the participants at the conference as they heard and saw the dead actually telling his or her story.

Iman Al Shanti, for example, raises a question: “Do you truly hear us?” Her home in Gaza City was bombed, killing her, her husband and three children.

Ayman Al Yedi was killed in an Israeli air strike outside the hospital where his baby was born later that day. The unspeakable sadness of this moment is vividly brought across to the viewer.

You hear Mustafa Al Sawaf, with 40 years of experience as a journalist and analyst, who was killed along with his wife and two sons in their home, say, “We are still here.” Samer Abu Daka was killed while doing his job as a photographer, Hiba Abadila perished in an Israeli strike along with her young daughter.

Each story is a profile in courage, each raises the question: how could this have been allowed to happen?

The installation, said Hana, was inspired by a poem written by Refaat Alareer, a professor of English literature also killed by the IDF in 2023. Titled ‘If I must die’, its first lines read: ‘If I must die,/you must live/to tell my story’.

That is what ‘The Last Minute’ attempts to do. As Bilal Khalil, general director of the Tawasol Forum pointed out, “The best part of this effort was that it brought together young people from across the Arab region. Designers, photographers, journalists, computer engineers, all put their talents together to tell the world this story.”

It is a story that will remain a blot on humanity. The world chose to look the other way when over 200 mediapersons were killed in Palestine, making a mockery of international humanitarian law that specifically recognises the right to protection from harm of journalists who do not take part in hostilities.

Bilal Khalil, general director of Tawasol 4, and Hana Almir, graphic designer of the installation, 'The Last Minute'. Photo by author.

§

Al Jazeera: ‘We threw a stone into what was a placid pool’

The Doha-based Al Jazeera, set up in 1996, now broadcasts to over 430 million homes in 150 countries and has bureaus in over 70 countries, according to its own data. I caught up with Aladdin Hammad, a senior editor of the channel during the Tawasol 4 conference at Istanbul, on how his channel was able to create – in the words of one journalist – a ‘real-time anti-hegemonic narrative from an Arab perspective’. I was also interested in knowing about how it emerged as the world’s most important forum for media coverage of Palestine.

Hammad did not shy away from difficult questions, including one on why his channel, partly funded by the state of Qatar, was not sufficiently critical of the Qatari ruling dispensation. He responded, “Well, Qatar is a very small country with a population of 27.2 lakh and its people by and large are adjusted to the existing political and social order. There is no major evidence of wide-scale repression – if there was, we would cover it.”

Excerpts from the conversation:

“In an earlier day, it was only BBC, CNN and a few other Western media channels that had a monopoly over reporting from this region. They had a very limited agenda and only one narrative: essentially an Israel-centric one. The news put out was clearly biased against the Palestinians with little or no representation of their concerns and no Palestinian voices. We saw this play out at various points of time. As for the Arab channels, their content centred emphatically on their leaders and little else.

“One of the agendas for Al Jazeera when it first emerged was to be with the people, with normal people, not leaders. Initially its popularity was based on its programmes rather than its news bulletins and most people don’t know this. But once it decided to focus on news, it had an immediate impact. For the first time the Arab people they were listening to two narratives rather than a single one.

“After the second intifada in 2000, we started covering Palestine seriously. Yet we always made sure we had Israeli voices too on the screen. The international impact of the channel grew.

“In 2003, after the Iraq invasion, even CNN picked up our footage for coverage on what was going on in that country. Our interview with Osama Bin Laden was used by several world broadcasters. In fact, after the Iraq invasion, BBC and CNN started taking regular feeds from us. In 2011, when the first of the Arab uprisings broke out in Tunisia, we put out the news over multiple channels, including our social media ones.

“Circumstances made Al Jazeera focus on Palestine, and the Palestinian issue was accorded special treatment by the channel, paving the way for it to emerge as the primary platform for coverage on Palestine.

“We believe our coverage has shifted public opinion in the region. People are now beginning to call out their leaders. When a military coup was taking place in Egypt, we held the attention of all Egyptians. It is as if we have thrown a stone in what was earlier a placid pool. Now every single channel in the region has discussion shows. We try to be as professional as possible in our coverage. We always allow the other side a presence. This is not happening in Israeli media, for instance.

“You could say Israel’s Palestinian policies led to a growing crisis, but we could never have anticipated what happened on October 7. We just did not expect such a scenario. We knew there could be individual strikes of resistance, but we never imagined that it would be a military one. I was on the shift that day and I can tell you that we were shocked. The movement on the ground, the air power … In some ways it was like September 11; it was as unexpected as the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad in Syria.

“Of course, being on the ground, Al Jazeera was able to broadcast all aspects of that attack in the immediate aftermath and later. But we paid a huge price. We lost journalists – four in direct hits; five indirectly.

“Today Al Jazeera viewers far outnumber those of its counterparts in the region, including prominent ones like Sky Arabia and the Saudi-owned Al Arabiya. I can also say that although we may not be allowed to function freely in, say, the US, for instance, the influence of our reportage on Palestine cannot be denied, it has become worldwide. Even people not watching us have been influenced by our coverage.

“Gen Z are not blind, they have learnt to check facts. When the false narrative of beheaded babies was deliberately spread by Israel in the immediate aftermath of the October 7 strikes, many young people perceived it as fake. I believe Kamala Harris lost the US elections because of this generation. This shows you that the future is on the side of media that strives to be as credible as possible. You cannot lie with impunity, thanks to social media and tools like TikTok.

“History will judge Palestine as one of the biggest conspiracies that the world has ever witnessed. It is the last colonial occupation in history and hopefully will remain the last.”

§

Billionaires as media barons let journalism down

If there is anything that the Trump victory proves, it is that while billionaires may pride themselves on being media barons, they are totally undependable when it comes to protecting media freedoms.

The stampede to curry favour with the new commander-in-chief is an eloquent example. As we all know, the owner of the Washington Post (WaPo), Jeff Bezos, stopped the editors of WaPo from endorsing Kamala Harris, which in turn led to the resignation of its editors and the cancellation of 250,000 digital subscribers (a tenth of its digital subscriber base).

WaPo, incidentally, was the very same newspaper that had counted more than 30,000 false or misleading statements Trump had made while in office during his first term!

Jeff Bezos’s meltdown is proof enough that in crunch situations, when media independence is pitted against currying favour with the ruling elite to protect corporate interests, the scales tilt sharply in favour of the latter.

Former executive editor of the Los Angeles Times (LAT), Norman Pearlstine, in a Columbia Journalism Review piece titled ‘Trump, the Public and the Press’, recalled how Patrick Soon-Shiong, owner of the LAT, had actually publicly criticised Trump’s handling of the pandemic in 2020 for his anti-vaccine stance. Yet this time, he made a grovelling statement congratulating Trump and his secretary for health and human services, anti-vaxxer Robert F. Kennedy Jr., on their “great decisions” in appointing “highly qualified critical thinkers” to lead the Food and Drug Administration.

Pearlstine noted that this shift in stance has had an immediate and chilling impact on the LAT newsroom. He also cited Time owner Marc Benioff’s fulsome endorsement of the president, who figured as the Person of the Year on the Time cover: “This marks a time of great promise for our nation. We look forward to working together to advance American success and prosperity for everyone.” Then there was the other media giant, Walt Disney Co., contributing $15 million to the Trump Presidential Library.

Meanwhile, the 47th president has already displayed his remarkable low threshold for criticism, promising to sue those who dare slam him. The US media has always projected themselves as a universal force for free speech. Let’s see what four years of the Trump presidency do to that claim.

§

Readers write in

Keep up with the times

The new year has brought its share of criticism. This mail (edited to remove personal comments) is from N. Venkatesh…

“You may recall the time, circa 2001, when mainstream media--at least in the West--started to become literally unbelievable and folks started moving to alternate media? Or maybe for you it was 2016, when masses of people called the bluff on legacy media and moved en masse to social media? Right now, The Wire risks being caught in the third wave of that movement - on the precipice of being considered irrelevant - as people move from The Wire and Scroll–long form reads to curated social media and rumble/substack. Before you delete this mail I want to say I am still a just-about loyal scanner of your pages. In a time when primary information is ever more readily available why does the The Wire platform folks writing on irrelevant issues?”

Write to ombudsperson@thewire.in

This article went live on January twenty-fifth, two thousand twenty five, at forty-four minutes past nine at night.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.