As a major Bollywood enthusiast, much of my time at the beginning of 2025 was spent going through the top box office hits of 2024. This included big-budget spectacles like Kalki 2898 AD, Singham Again, Fighter, Amaran, Hanu-Man and Article 370 – films that dominated the industry and raked in hundreds of crores.

A faint pattern slowly settled in my mind. Beyond their high-octane action and visual grandeur, many carried a deeper undercurrent – one steeped in nationalism, anti-Muslim sentiments and pro-Hindu ideologies.

It would be easy to argue that the audience is to blame. Bollywood thrives on demand, and these films succeeded because millions flocked to theatres and glorified majoritarian ideals. But is it that simple?

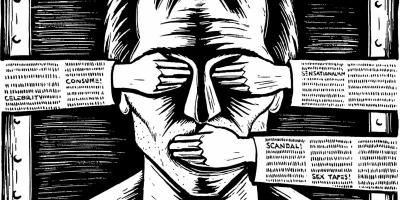

When movies that challenge this dominant narrative struggle to find screens, face online smear campaigns and are quietly buried before making an impact, the question shifts from audience preference to institutional influence. What role does government censorship and broader press suppression play in ensuring that these films – ones aligning with state ideology – become blockbusters while others are silenced?

The answer lies in the broader media ecosystem, where the Indian government’s grip on the press ensures a seamless alignment between state ideology and cultural output. From punitive tax raids on dissenting media houses to the systematic targeting of critical journalists, India’s press freedom has eroded at an alarming rate. This suppression extends into entertainment, where filmmakers risk severe backlash if their work deviates from the nationalist script.

In such an environment, can we really call this a free marketplace of ideas, or is it an illusion of choice where the state curates what we consume?

India is not alone in this crisis. Across South Asia, press freedom has been under siege.

Pakistan experiences an even more overt form of censorship, where journalists critiquing the military or government face abduction, torture or assassination. In the film industry, censorship is rigid, and authorities have outright banned movies that challenge state narratives. Zindagi Tamasha (2019), a film exploring religious hypocrisy, was banned after hardline Islamist groups protested its release. While India’s suppression takes economic and institutional forms, Pakistan’s is enforced through sheer coercion.

Bangladesh and Sri Lanka have also over the years seen reporters arrested and media houses pressured into self-censorship.

The trend suggests a coordinated effort to limit independent storytelling, whether through legal intimidation or outright violence.

Now, contrast this with Germany, where press freedom is enshrined in the constitution and rigorously protected. Investigative journalism flourishes, with the media holding the government accountable without fear of retribution. Films like The Lives of Others (2006), which critiqued East Germany’s surveillance state, received widespread acclaim without facing state interference.

The stark difference lies in the approach: whereas South Asian governments deploy legal, economic and violent means to suppress dissent, Western democracies generally uphold press freedom as a pillar of governance rather than a threat to stability. Even when controversial subjects are broached, the state does not weaponise institutions to silence dissenting voices. Instead, competing narratives coexist, allowing audiences to engage with multiple perspectives.

What makes India’s case more insidious is the veneer of choice. While Pakistan’s press restrictions are blatant and Germany allows for greater dissent, India operates in a grey area – where suppression is masked as regulation and state-friendly narratives are amplified through financial and structural advantages.

The ruling party doesn’t need to ban critical films outright; they simply make it economically and logistically unfeasible for such projects to survive. If a film doesn’t align with the nationalist agenda, it is quietly choked out of the market through denied tax incentives, difficulty securing distributors or relentless harassment from government-aligned trolls.

Meanwhile, films celebrating government ideologies receive overwhelming institutional support, including tax breaks, aggressive promotion and endorsements from political figures.

This creates a lopsided cultural landscape where the audience has the illusion of choice but no real alternative narratives.

So where does that leave us? South Asia’s decline in press freedom – and by extension, cultural freedom – is not just a warning for journalists and filmmakers; it is a red flag for democracy itself. A government that controls the stories a nation tells itself is one step away from controlling how its citizens think and vote.

The slow death of media independence doesn’t happen overnight; it creeps in, disguised as patriotism, economic policy and ‘cultural protection’. By the time the public realises the extent of its erasure, dissent has already been reduced to a whisper.

The danger is not just in what we see, but in what we are no longer allowed to see. As Bollywood continues to churn out spectacles reinforcing a singular ideological viewpoint, one must wonder: how many stories were never even allowed to be told? And what does it say about a democracy when its people are only given one version of the truth?

Mansi Anil Kumar is from Bangalore and is currently a sophomore studying economics at Yale University.