Hindi Visual Media is in a Meme Trap

A journalist from Bihar recently posted on Facebook that the election coverage of Hindi media’s visual journalists visiting his state feels like ‘poverty porn’. Hindi media is not alone – many look at Bihar not as a society but as a spectacle. What the journalist wrote is true for a large section of Hindi media which – thanks to the public response it generates and the influence it holds – has become the representative journalism of the language.

Hindi may have had some of the largest selling newspapers in the country but its glittering icons over the last few decades have arrived from the visual form earlier on TV, and now on YouTube.

Today, the most prominent Hindi journalists – and you can choose the ones according to your political inclination – belong to the world of the screen.

It is a unique phenomenon where the most notable journalists of a language which is spoken by over 600 million people in India and sees numerous print publications, have eschewed the written platform.

In contrast, the English journalism space in India offers an entirely different landscape populated by countless bylines, faces you might never recognise, and voices that are not always found on camera.

English media anchors have a massive social media influence but face sufficient criticism for their theatrics and loudness. These anchors, several of them carrying a badge of secularism, may struggle to find a place among one’s favourite journalists. The similarly shrill Hindi anchors somehow escape scrutiny as long as they carry a copy of the constitution and cite Nehru.

The last 10 years have seen several independent media organisations emerging in both Hindi and English – the former has largely taken to YouTube while the latter mostly focuses on text stories, at once attempting to find a footing in video. While English journalism still nurtures long-form reportage running into several thousand words, the genre appears to be vanishing from Hindi.

Don’t blame it on lack of funds. It’s the sheer approach towards journalism.

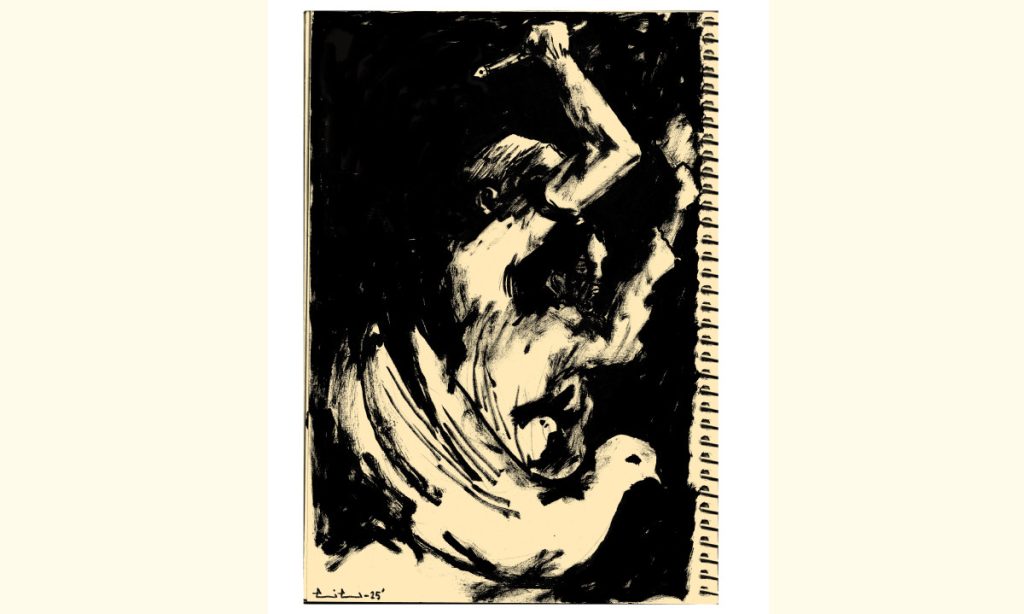

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty.

Of late, the matrix of the gamut of visual journalism in Hindi has rested on three broad genres. First, extract a clip out of someone’s misery or a person’s wisecracks and make it viral. This is a form of reporting in which going deeper into an issue has no rewards. Just step out with a camera, replace rigour and precision with rhetoric and arrive at a viral clip. A witty remark by a villager can alone offer you a video that trends all day on social media and earns you a handsome revenue. But this form of journalism turns the countryside into a circus and the citizen into a clown.

Another popular method is to lift an investigative report and read out its summary in spicy Hindi before a camera. To add some authenticity, some Hindi YouTube channels invite the English reporter who broke the story. Since the Hindi anchor likely commands a bigger presence on social media by virtue of the language’s numerical strength – and since the English readership is minuscule compared to the vast audience that understands spoken Hindi – the story spreads. In public memory, the investigation now belongs to the Hindi anchor.

Third, is the popular option of chitchatting with celebrities. Conversations about their secrets, struggles and love lives make for more viewership.

To be sure, journalism in English has its own dark alleys, compromises, and collusions. And enough is being written about it. My point is simply this: Hindi journalism – which once had some of India’s most respected newspapers, journals and editors – is now becoming devoid of nuances and complexities. The Hindi audience is offered pieces no longer than 600 words, and instead served videos of unfiltered entertainment dressed up as journalism.

Video journalism is a fine art; the camera is an extraordinary creative instrument. But the camera of many YouTubers remains mostly confined to the noises and gestures on the surface. Could it also be that because the YouTube model, rooted to reward extreme behaviour, is designed and deployed to harvest likes and retweets? It may bring easy revenue, but I believe it damages journalism in the long run.

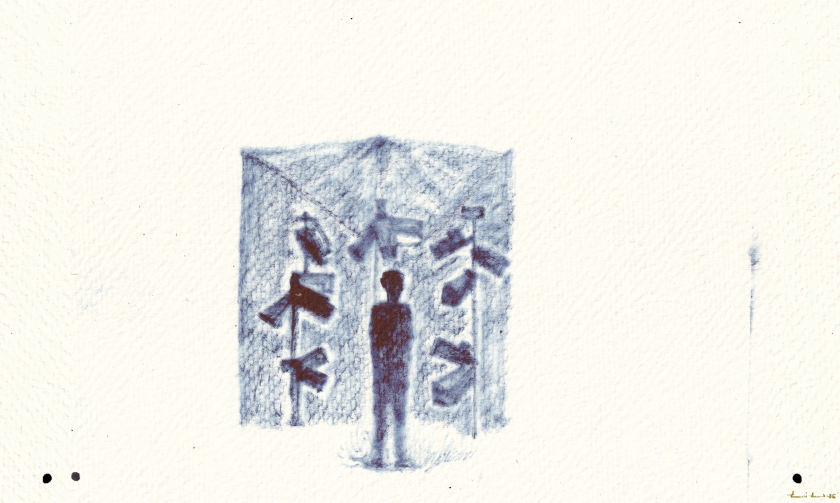

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

It perhaps began with the search for an alternative business model around the time the governments stifled the media. Social media platforms provided an easily and readily available alternative. But the need for revenue has made rigour and discipline irrelevant.

Chasing easy views on the ground, Hindi journalists on YouTube have abandoned crucial issues like shady business deals, coal allocations, wrongful allotments of mines, defence, international politics, economy, science and technology, geostrategic affairs.

Perhaps because these issues can’t be covered by a parachute visit with the camera. It requires perseverance to build an ecosystem that enables such reports, that prepares a team of dedicated reporters who can work on documents for weeks and months, and that mandates a disciplined editorial desk to craft stories out of raw material.

In a country, where regional journalists are killed or arrested for focusing on corruption at the ground, the indifference of bigger names in Hindi towards reporting on national issues is appalling.

The surrender of what is now called godi media are well-documented. But the failings of the independent Hindi media have somehow escaped scrutiny. These journalists must know that the models they have employed often take the viewer for granted, weaken journalism, and consequently damage democracy.

A few years ago, it was the threat of hashtag journalism that had been killing hard-earned reporting and rewarding idle influencers. The YouTube model has carried forward the game several notches ahead. How this phenomenon is transforming the Hindi society, its politics and democracy, is for sociologists and historians to assess.

All I can say as a journalist is that it is also damaging journalism in the language. As a resident of the Hindi belt, it’s making my fellow citizens complacent. And as a citizen, if journalism doesn’t make you a better participant in democracy, if it makes you an idle viewer of a spectacle, it benefits the ruling dispensation.

Visual mediapersons are often celebrated as content creators. The difference is telling. News is gathered; content is created. A long time ago some English newspapers had turned their pages into business models. It’s the Hindi content creator now.

This article went live on November fifth, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-seven minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.