In a World Where War Photographers Win Prestigious Prizes, Gaza Journalists Are Sentenced to Death

Amidst my social media mix of giggle-worthy memes, gut-wrenching news, a live-streamed genocide and other algorithmic distractions, an image of a shattered blood-soaked camera reached my feed. I stared at it for a little longer than usual. The caption says that the camera belonged to Mariam Abu Daqqa, one of the five journalists killed in the Al Nasser hospital in the south of the Gaza Strip on August 25, 2025, along with Hussam al-Masri, Moaz Abu Taha, Mohammed Salama and Ahmed Abu Aziz.

This made the total number of journalists killed in Palestine so far to 220. These journalists worked for agencies including Reuters, Associated Press and Al Jazeera. Hours later, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu regretted the “tragic mishap”.

“Our war is with Hamas terrorists. Our just goals are defeating Hamas and bringing our hostages home,” he said while the IDF continues its dance of death in Gaza.

India called this attack on journalists “shocking and deeply regrettable” while also continuing its arms exports to Israel.

A family handout photo showing the blood-stained camera that Mariam Dagga was carrying when she was killed. Photo: AP/PTI

Being a multimedia journalist, the image of Mariam’s camera forced me to pause my doomscroll and reflect upon her journey. Her friend Youmna El Sayed remembers her in an article for Al Jazeera as someone who was striving to capture all the moments – the moments of grief, of pain, sorrow, laughter and love in Gaza.

While the moments of love and laughter seem painfully scarce for the people of Gaza, her intention to document the genocide in Gaza must, in my imagination, have been to let the world know what is being done to her people. Not just her, but all the journalists who, with every adjustment of the ISO and aperture, might have thought to themselves that maybe this image will shake the world from its long slumber, which seems to have normalised looking at the images of maimed, orphaned children and beheaded babies.

The question is, has the world always been this insensitive, ignorant and callous to the suffering, or is this desensitisation a new norm?

To answer this, I collected some of the most moving and powerful images in the history of war journalism that jolted the world before social media reduced our capacity to feel.

On war and starvation

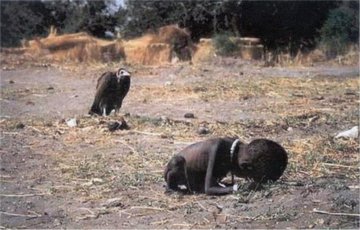

While data and figures fade from our collective memory, an image imprints the sorrow upon our soul and gives a face to the tragedy. One such image that is etched in the minds and hearts of millions is The Vulture and the Little Girl by Kevin Carter. The image was taken during the second Sudanese civil war (1993 to 2005), a conflict between the Sudanese government and Sudanese People's Liberation Army over religion, ethnicity and the control of the oil resources.

Kevin Carter'a Pulitzer winning 'The Vulture and the Little Girl' photograph from the Sudanese civil war. Photo: Wikipedia

The war claimed the lives of 20 million people. More people died of famine and disease than from direct combat.

Another haunting chapter from history is captured in the harrowing images from the Bengal Famine. Skeletal bodies with sunken eyes, these children were the victims of mass starvation caused by World War 2 and the failed policies of Winston Churchill.

Willoughby Wallace Hooper’s photos of the famine. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Library Image Catalogue/Public Domain

These images speak volumes about the cruelties inflicted upon the most vulnerable in the history of the world, but the story that Mariam’s camera longed to tell was silenced forever. Every day, countless such images appear on our social media feed from Gaza. The images of stolen childhood where children shoulder the burden of bringing home food from the aid centres. Some return home with a pan filled, others come back with an empty vessel, and some never return at all.

Mothers and children

In 1936, Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange became the face of a mother’s endurance in the Great Depression. The subject, Florence Owens Thompson, a 32-year-old mother of seven children, was seen struggling to survive during the Dust Bowl migration. The image was taken in Nipomo, California.

'Migrant Mother' by Dorothea Lange, 1936. Photo: Wikipedia

Florence was pictured with a creased forehead, her three tousled children resting against her shoulder as she stares into an uncertain future.

Another among the most poignant images of recent times is that of Alan Kurdi, a two-year-old Syrian refugee whose lifeless body was found washed up on a beach in Bodrum, Turkey. Alan was one of at least 12 people who drowned attempting to flee the Syrian Civil War. Alongside him, his five-year-old brother Ghalib and their mother Rehanna also met a similar fate when the overcrowded inflatable boat they were on capsized while trying to reach the Greek island of Kos.

Death of Alan Kurdi, as photographed by Turkish photographer Nilüfer Demir. Photo: Wikipedia

This tragic image, captured by Turkish photographer Nilüfer Demir, lingers vividly in my memory. It became a powerful symbol of the refugee crisis, drawing global attention to the plight of displaced families seeking safety. The image of the young boy in his bright shirt, lying face down, was carried across every news channel, newspaper and social platform. It was a time when the world’s conscience still seemed to stir.

What is surprising is the silence that meets the suffering of Palestinians – the western media’s adultification of the Palestinian children and its ignorance when it comes to addressing the trauma of Palestinian mothers who are grieving the loss of one child while struggling to keep the others alive, shielding them from starvation, displacement and Israeli bombardment.

It fills me with disbelief how the world has turned a blind eye to the mothers and children of Gaza when our collective conscience has a capacity to change so much about this world.

Pain, prisoner, Palestine

Pain imposed in prison, with or without being proven guilty, is not new in India. Our country has its own record of being ruthless to its prisoners. Recently, the 12 men acquitted in the 7/11 Mumbai train blasts recalled how they were subjected to custodial torture and forced into fake confessions. The 12 men lost 19 precious years of their lives before they were proven innocent.

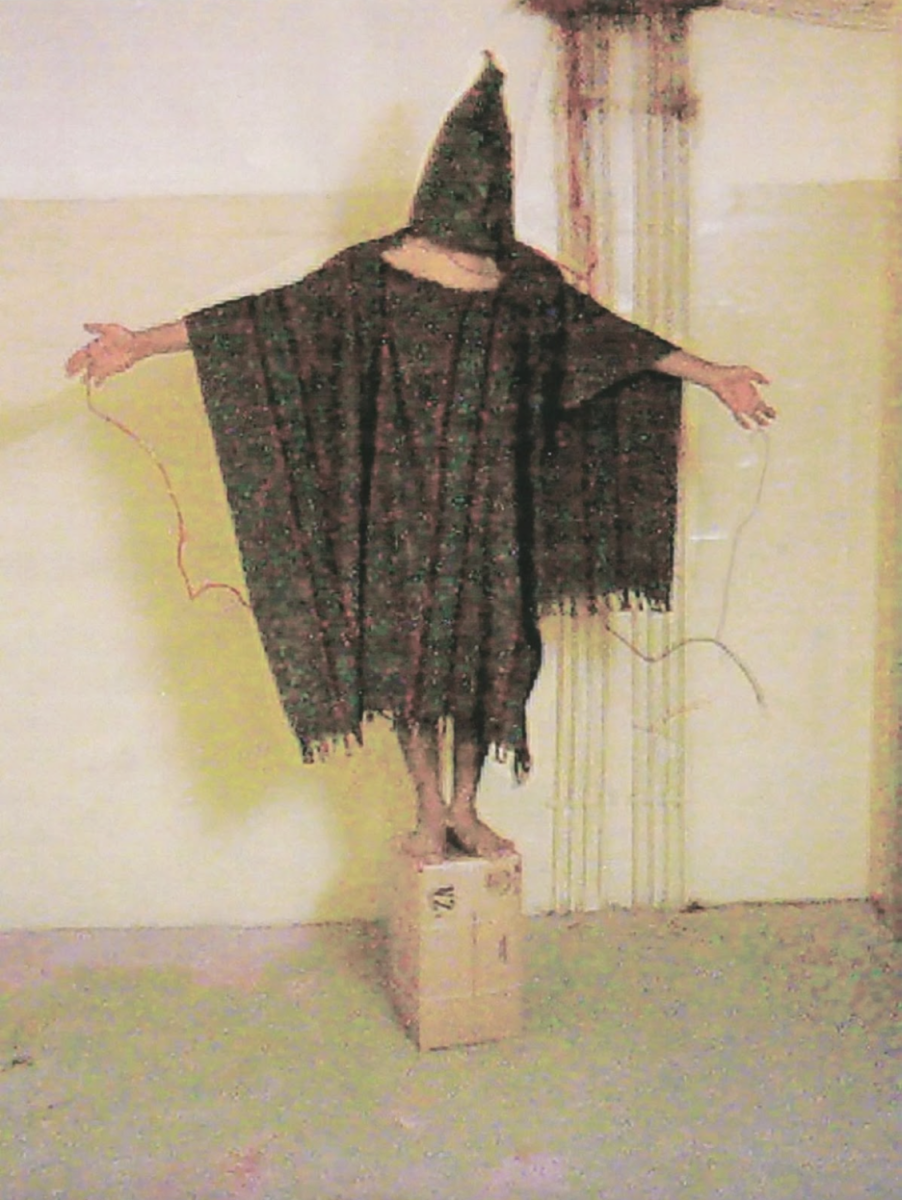

In 2003, when the US initiated its infamous “war on terror” and invaded Iraq, images soon surfaced showing Iraqi prisoners suffering at the hands of American soldiers. One such image is of a hooded man standing on a fragile cardboard box with his arm outstretched with a wire attached to his fingers and around his neck. He was told that if he slipped off the box, he would be electrocuted.

This prison is called Abu Ghuraib, a maximum security prison used by the US soldiers to “interrogate suspects”. The facility was earlier used by Saddam Hussein during his presidency between 1979 to 2003. The image is one of the many that appeared during 2003, testifying the humiliation prisoners went through, including sexual abuse, rape, and physical and psychological torture.

In 2008, a lawsuit against California Analysis Center, Inc. (CACI) was filed by these Iraqi Prisoners in which 11 US soldiers were charged with dereliction of duty, maltreatment, and aggravated assault and battery. A US jury ruled that CACI must pay 42 million dollars to these men who went through this pain.

'The Hooded Man', a photograph of Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, an Iraqi prisoner, being tortured, that became internationally infamous. Photo: Wikipedia

When images from Abu Ghraib prison became public, they sparked international outrage and led to action against the U.S. soldiers involved. This stands in stark contrast with the treatment of Palestinian prisoners, which receives no accountability.

For years, images and testimonies have shown innocent Palestinians subjected to immense torture at the hands of the IDF. Yet, the world’s response remains muted.

Chemical weapons vs children

When a war photographer picks up a camera, their intention is not merely to document war, but to capture a moment that cries out to the world, “never again.” The same holds true for Nick Ut, who in 1972 captured the iconic photograph “Napalm Girl”, a young Vietnamese girl, Phan Thi Kim Phuc, running naked down a road, her skin burning and melting from napalm. Napalm is a highly flammable chemical substance used by the US during the Vietnam War.

While Kim Phuc stands at the centre of the frame, the image also reveals other children around her, crying in terror as soldiers follow behind them. In the distance, plumes of soot and smoke rise.

'Napalm Girl', a young Vietnamese girl running naked down a road during Vietnam War, as captured by Nick Ut in 1972.

Having suffered the pain of losing a brother to the war, Nick says, “I wanted to stop this war. I hated war.” He succeeded. The black and white photograph came to symbolise the horrors of the Vietnam War and became a powerful catalyst to mobilise the world and end the conflict.

But just half a century later, history repeated itself. The incident was the same; the geography, different. As per reports, Israel has been using white phosphorus on the citizens of Gaza and Lebanon. It is a lethal chemical that burns human tissues when exposed to oxygen. It burns at more than 800 degrees Celsius, which is high enough to melt metal.

The images and reports that circulated earlier got lost somewhere in our feed, leaving permanent marks on those who suffered from the chemical burns.

The photographers mentioned in this article won prestigious awards, and rightly so. Both Kevin Carter and Nick Ut won Pulitzer Prize for their notable work. Their lens helped change the course of war but my question remains the same: shouldn’t Mariam and those like her be alive today?

Or is death the cruel price they were forced to pay simply for telling the story the world needed to hear? The same world that awarded other war journalists with prestigious prices painted the lens of a Palestinian journalist with blood. The cruel irony laughs at our faces for our hypocrisy.

This article went live on October seventh, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-one minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.