Three Irreverent Indian Publications of Colonial Times Have a Lesson for India's Media Today

Three irreverent Indian publications from the late 19th and early 20th centuries – which impudently challenged British colonial authority through satire and lampooning – stand as a rebuke to today's quiescent media outlets and their compliant journalists, who bear joint responsibility for India's well-documented decline in press freedom since 2014.

Published in English, Urdu, and Hindi, these three saucy publications – modelled after England's witty Punch magazine which was founded in 1841 – flourished between 1854 and the mid-1930s in Lucknow, Bombay, and Indore.

The three persistently used parody to mock their despotic and pompous British rulers. These were the English-language Parsee Punch, founded by Pestonjee Marker and published from Bombay between 1854 and 1931, followed by the Awadh Punch in Urdu, launched by Munsi Sajjad Husain in Lucknow in 1877 and lasting till 1936, and the Hindi Punch, instituted by Nowrosjee Barjorjee in 1906, that ran uninterruptedly for three decades, till 1936.

They had their linguistic and regional differences but all three publications maintained a defiant editorial stance against the callous colonial administration – one that was markedly harsher than even today's oppressive media environment under Narendra Modi’s BJP government since 2014.

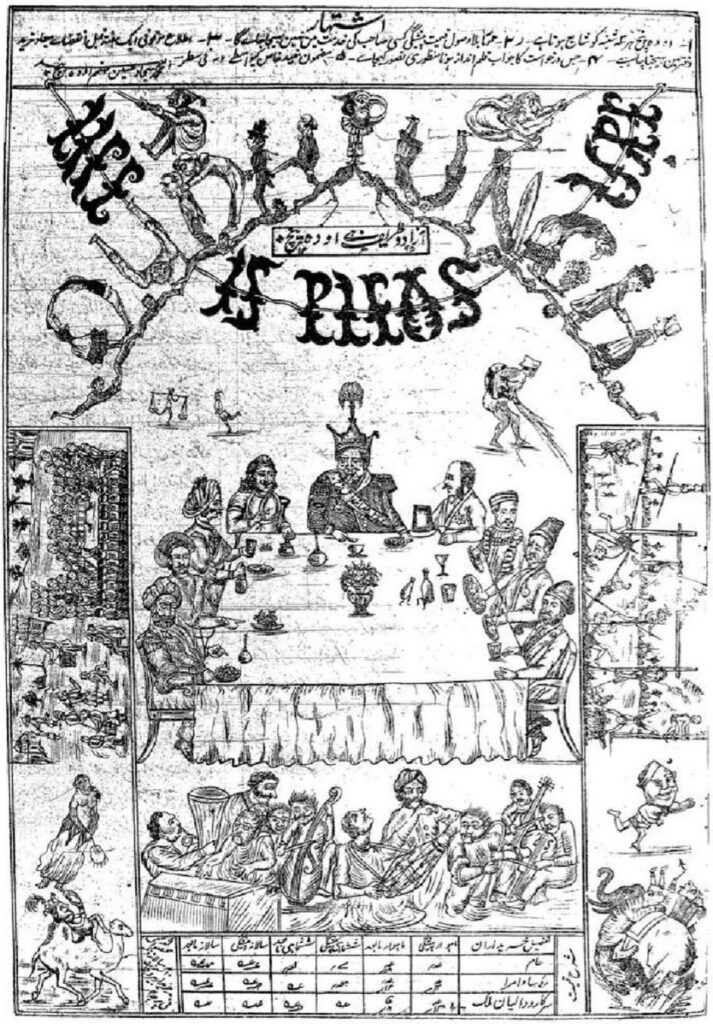

A page of the Awadh Punch. Photo: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite the severe limitations of printing technology, widespread illiteracy, and a highly restrictive atmosphere, this Punch trinity tenaciously fulfilled what today's tech-savvy, AI-enabled Indian media is too timid to attempt: speaking truth to power. Unlike these colonial-era predecessors, modern media outlets have shamefully abandoned their role of scrutinising government actions, exposing corruption and misgovernance, and challenging the flagrant abuse of state power by both official and wealthy private entities.

The collective Punch publications also severely critiqued local politics and social mores, especially practices that perpetuated caste and community inequalities. Through bold illustrations, they mercilessly mocked Indian elites who collaborated with colonial administrators, portraying them not merely as fawning sycophants but as absurd figures. Their most vicious derision was reserved for the obsequious 'ji-huzoor' types and the 'England-returned brown sahebs' (or 'coconuts' who were brown outside but white inside. This group had maharajahs, lesser royals, and social climbers who slavishly embraced English fashion, accents, and manners while fawning for titles and gun salutes from their British masters.

Far ahead of their time, these publications tackled controversial issues like religious orthodoxy, comically portraying local religious leaders and zealots as self-serving exploiters while criticising the masses' blind adherence to rituals. They also assailed casteism and the dowry system, highlighted growing wealth disparity, and addressed the subordinate status of women in society, particularly regarding their education, social emancipation, and rights.

Circulation numbers were modest, to put it charitably, as these publications were constrained not only by inefficient and expensive printing equipment but also by abysmally low literacy levels. However, research into these titles reveals they had a surprisingly strong impact on shaping local public opinion and discourse, achieving influence disproportionate to their limited circulation.

The Awadh Punch initially printed 250 copies of its folio-sized, eight-page edition, soon increasing to 500. Each copy cost 4 annas, with an annual subscription priced at Rs 12 (equivalent to approximately Rs 2,100 today). In comparison, the Parsee Punch's circulation ranged from 400 to 700 copies, with an annual subscription of Rs 6. This lower price reflected both Bombay's larger metropolitan readership and the reduced production costs for English-language periodicals compared to Urdu publications.

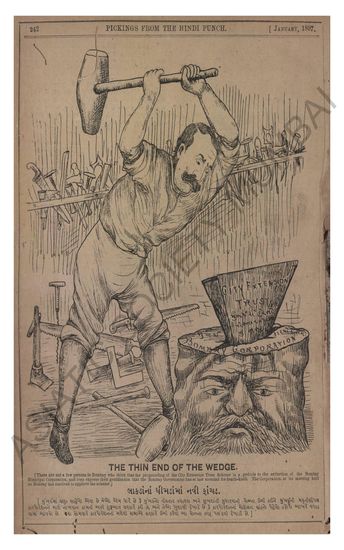

The Parsee Punch's monthly compilation "Pickings from the Parsee Punch," running 24-36 pages, was a runaway hit. Its scathingly humorous illustrations targeted both British officials and the Parsi community's identity crisis, caught between traditional Zoroastrian practices and aspirational English lifestyles. The Hindi Punch, which shared founding connections with the Parsee Punch, achieved a weekly circulation of around 800 copies and was similarly priced at Rs 6 per annum (approximately Rs 1,100 today).

A cartoon, purportedly on the Parsee Punch. Photo: Facebook/Dew Media School

In all three publications, a succession of creative and fearless editors, supported by equally bold writers, contributors, and cartoonist-illustrators, skilfully wielded satirical humour as a weapon against colonial rule. They particularly excelled at mocking British officials' comical struggles to understand native customs, norms, and languages, highlighting the profound cultural disconnect between the rulers and the ruled.

According to the history and politics blog "Contested Realities", the Awadh Punch's satire and cartoons "repeatedly poked a finger in the British government's eyes at every opportunity." The blog cites historian Mushirul Hasan's book, Wit and Humour in Colonial North India, which notes that the weekly's cartoons, published with impunity, offered rare insights into India's political and cultural history.

Also read: Against Odds, India's Political Cartoonists Will Watch the Watchmen

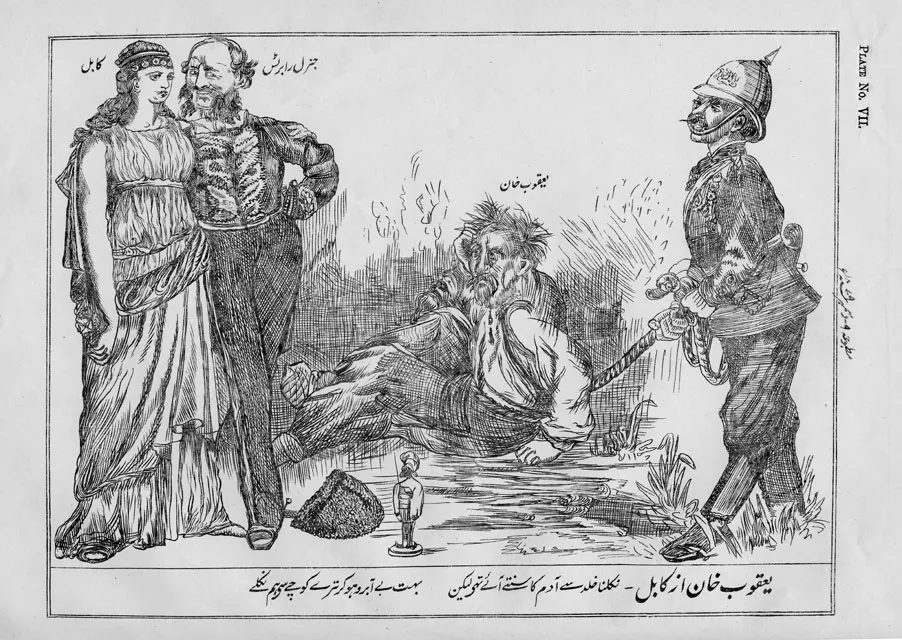

A cartoon from the Hindi Punch, 1897-1898. Photo: Asiatic Society of Mumbai, www.granthsanjeevani.com.

One such illustration, depicting greedy British officials grasping India’s wealth under the guise of ‘civilising’ the natives, has colonial officials wearing outsized crowns juxtaposed against struggling and skeletal Indian figures. Another has a British officer dressed in military regalia seated on a throne labeled "Justice," while beneath him, Indian peasants toil in chains. Its caption reads ‘Insaf ka Taj’ or ‘crown of justice’, highlighting the venality and callousness of colonial governance, which claimed fairness, whilst starkly propagating exploitation.

Russia’s role in the intrigue-ridden Great Game in Afghanistan, which drove both the British Raj in India and its government in London into panic in the late 19th century, too, was impertinently but absurdly caricatured in a drawing in the Parsee Punch of a bear embracing a burqa-clad Pashtun woman.

Together, the Punch publications commented on the growing nationalist movement and the tensions between moderates and extremists in the emerging independence struggle.

A notable Parsee Punch cartoon depicted Indian leaders arguing over petty issues while an unconcerned British imperial lion watched from afar, highlighting the disunity among freedom fighters.

Though the Hindi Punch may not have achieved the same recognition as its counterparts, contemporary accounts credit it with significantly shaping public opinion and establishing satire as a form of resistance during times when direct political dissent was viciously suppressed.

A cartoon from Awadh Punch on Afghanistan, 1879. Photo: The Public Archive http://thepublicarchive.com/?p=1921 via https://contestedrealities.wordpress.com/2015/01/18/awadh-punch-indias-charlie-hebdo-of-past/.

This brings us back to India’s press freedom ranking of 159 out of 180 countries surveyed in the World Press Freedom Index released by Reporters Without Borders in May 2024. Non-governmental organisations like Amnesty International, the Human Rights Watch and the Committee to Protect Journalists, amongst others also declared that the Indian authorities were increasingly targeting journalists for questioning the national and state BJP-led governments by prosecuting them, ironically under colonial-era sedition statutes.

Since 2014, numerous media organisations and their editorial staff, critical of the BJP have been charged either by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), the Enforcement Directorate (ED) or the Income Tax department – in some cases by all three – for assorted financial ‘wrongdoings’, which took years to adjudicate in India’s notoriously snail-paced and state-influenced judicial system.

Prominent television news anchor Ravish Kumar with a 9.4 million viewership of his YouTube channel, said that being a journalist in India today had become a ‘solitary endeavour’. Uncompromising reporters, he asserted, were forced out of their jobs by news organisations for their objectivity and their corporate owners were never questioned or held accountable.

He also stated that this media-businessman-politician nexus had spawned a ‘godi’, or lapdog press, which equally mixed populism and pro-BJP propaganda. Even six-time BJP MP Subramanian Swamy agreed, declaring on social media some time ago that India’s media had been ‘totally castrated’. The former Harvard economics professor, who was an MP till 2022, stated that those media organisations who stood up to the BJP government were invariably ‘visited’ by a senior official from the PM’s Office, who ‘threatened’ them with prosecution by either the CBI or the ED or both. He equated such actions to similar happenings in Russia and China with regard to the media.

But emulating the atmanirbhar or indigenous Punchs in today’s vastly altered social and cultural landscape of political correctness poses serious challenges. Topics that were once considered fair game for humour are now scrutinised for perpetuating stereotypes, marginalising groups or reinforcing inequalities.

What amuses one audience offends another, and with the global nature of media, satire that resonates in one cultural context is invariably misinterpreted or deemed distasteful in another. But broadly, mockery and ridicule challenging those in power, government structures or highlights societal absurdities, resonates better than parody that targets marginalised groups.

After all, it’s a universally accepted axiom that humour remains a vital tool for processing complex realities, challenging norms, and fostering dialogue. It also helps alleviate the obstacle-ridden grind of daily living, confirming the adage that humour makes life so much easier.

This article went live on January eighteenth, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-eight minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.