Recalling the Political Genius of Iconic Cartoonist Abu

Abu’s World, a major retrospective of the iconic cartoonist, Abu Abraham, on display at the Kerala Lalitha Kala Akademi Durbar Hall Gallery, in Kochi, is attracting visitors of all kinds, from purposeful aficionados to walk-ins who stay for a long time. Gallery staff attest that there have been many repeat visitors to the show, which marks the centenary year of the legendary cartoonist. Some visitors are content to spend an entire day taking in Abu’s works on just a single wall the way generations of readers would have mulled over his front-page political cartoon of the day in print.

For many visitors, these cartoons understandably evoke memories of past events, and of their intense personal experiences of trying to make sense of a volatile world mediated through Abu’s meditative lines on the front page of the Indian Express (1969 -1981). For instance, Ashok Kumar, a printer and type setter by profession, though highly appreciative of the exhibition, was disheartened that he couldn’t find the ‘Vietnam cartoon’, which he had come looking for. “It appeared on the front page, along with the news that Saigon had fallen. We had cut out the cartoon and put it up on our college notice board. I still remember it. It showed Vietnam as a resplendent butterfly breaking out of a bomb-shaped pupa. It was brilliant,” he recalls.

As many as 300 original works of Abu are on display at the Kerala Lalitha Kala Akademi Durbar Hall Gallery, in Ernakulam, Kochi. Photo: Gokul Gopalakrishnan

For younger visitors like playback singer and actress Resmi Sateesh, there is no such baggage of the past. A repeat visitor, she is excited by both the art and the sense of social and political history that the cartoons reflect. “I keep asking my friends to not miss this show,” she says. Her friend, whom she had convinced to accompany her, nodded in agreement.

Abu had a decade-long run with The Observer (1956-66) and a three-year stint with The Guardian (1966-69) before he returned to India. He worked with the multi-edition Indian Express from 1969-81. After that he syndicated his work to several newspapers. Given his fairly long career, especially during tumultuous times like the Emergency and the Cold War, it is only natural for the cartoons, in retrospect, to be seen as a record of social and political histories of the times.

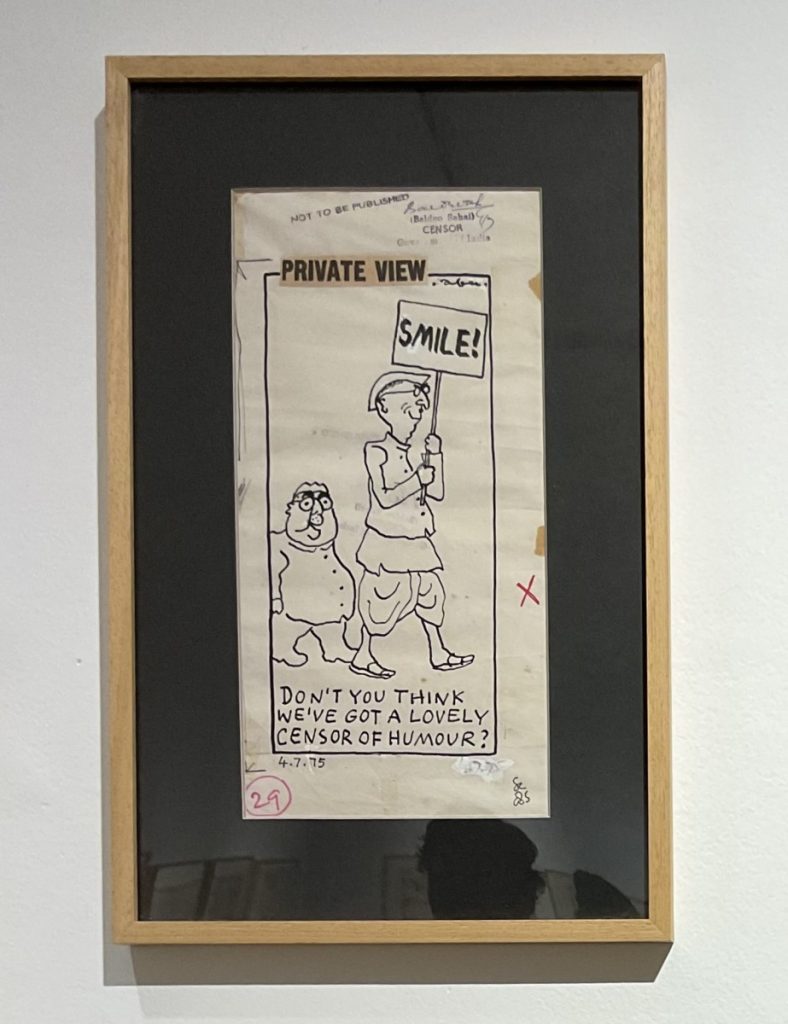

Abu’s pocket cartoon (4/7/1975), made during the Emergency, carrying the ‘not to be published’ stamp of the censor on top. Photo: Gokul Gopalakrishnan

However, that function of the daily cartoon in print is incidental, though no less important. Daily political cartoons assume greater significance for the immediacy of their response to unfolding events. The 300-odd original cartoons displayed at the show amply demonstrate this aspect of political cartooning on a day-to-day basis. Drawn for the daily consumption of the reader as an immediate comment on the day’s news, it can be quite transient in nature.

The originals on show retain all the marks of a cultural product situated within the prevailing ideological, commercial and governmental framework. You can see the editor’s scrawls and directions to the printer, the ‘not to be published’ stamps of the Chief Censor, during the Emergency, and whitened out lines.

The originals give you a sense of ‘being there’ ‘in that moment’, as if you are peering over the cartoonist’s shoulder to catch a glimpse of him going about the business of ideating and drawing the following day’s cartoon.

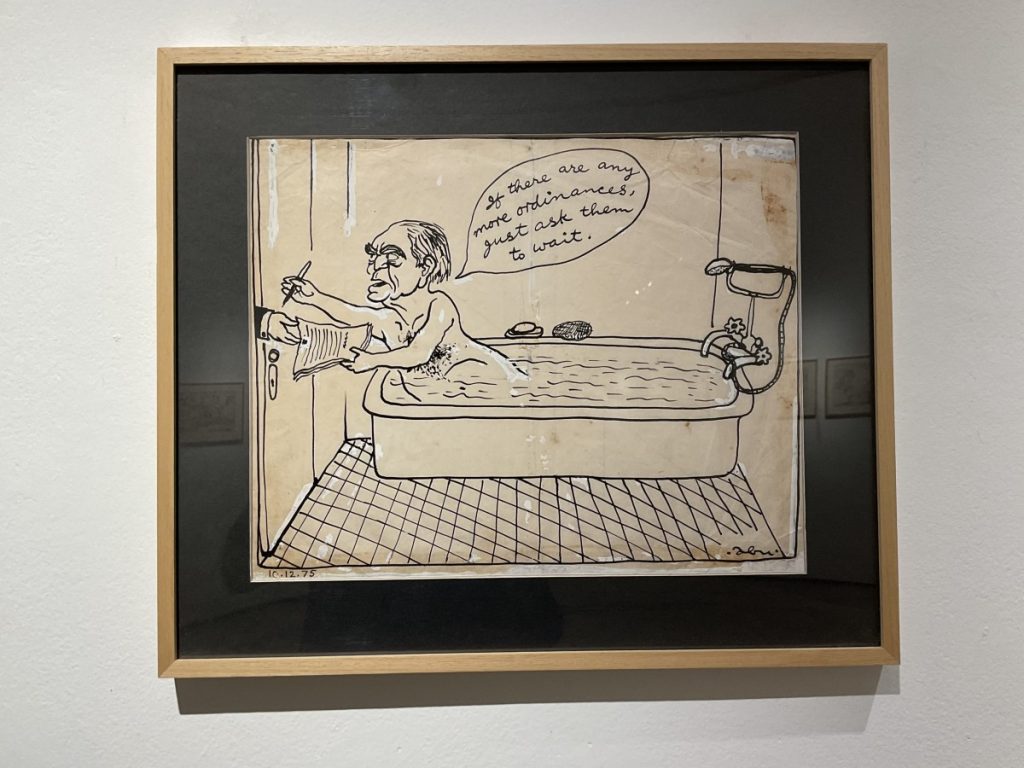

Take Abu’s famous cartoon of the President in the bathtub, drawn during the Emergency years. Highly disruptive and full of wry humour, it’s a wonder how it managed to escape the censor’s scrutiny and make it to the front page in print. Some maintain that Indira Gandhi let this one slide because she wanted to show the world that India still upheld democratic values.

Perhaps Abu’s most well-known work, this cartoon shows President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed extending himself from his bathtub to sign an ordinance during the Emergency.

We have seen the cartoon in question in print and online. It is often the first to pop up if you google Abu. But nothing prepares us for the original. There is the date, 10/12/1975, in one corner. One can see the lines of the bathroom door, floor tiles, and shower knobs corrected and whitened. The lines delineating the wall were redrawn to achieve better perspective, with President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed’s hip lines realigned to convey a sense of him floating in the tub. The panel outlines of the cartoon, too, seem to have undergone some last-minute changes. All tell-tale signs of a cartoonist at work, racing against a looming deadline to work through multiple possibilities to come up with a final version that would appear as a neatly printed cartoon on the newspaper’s front page the following day.

The exhibition has been well curated by Ayisha and Janaki, both daughters of Abu. By showcasing the cartoons in the context of critical junctures of history, through annotations contributed by historian Janaki Nair, the curators have successfully built up a narrative continuity. Juxtaposing the liminality of the daily cartoon in its original form with the permanence of its retrospective social/historical commentary, the show manages to bring out its inherent duality.

The show also does justice to the range of Abu’s consummate artistry by including original sketches, scrapbooks, copies of sketchbooks, comic strips, and even an award winning animated short film. Abu’s unhurried lines capture the feel and essence of the places and people he sketched, be it the figures of nuns enjoying some precious languid moments at the sea side, a Vijayawada shanty in the sweltering Andhra summer, two Shanghai monks about to break into conversation, or the resoluteness of sunbaked fishmongers on the Kovalam beach.

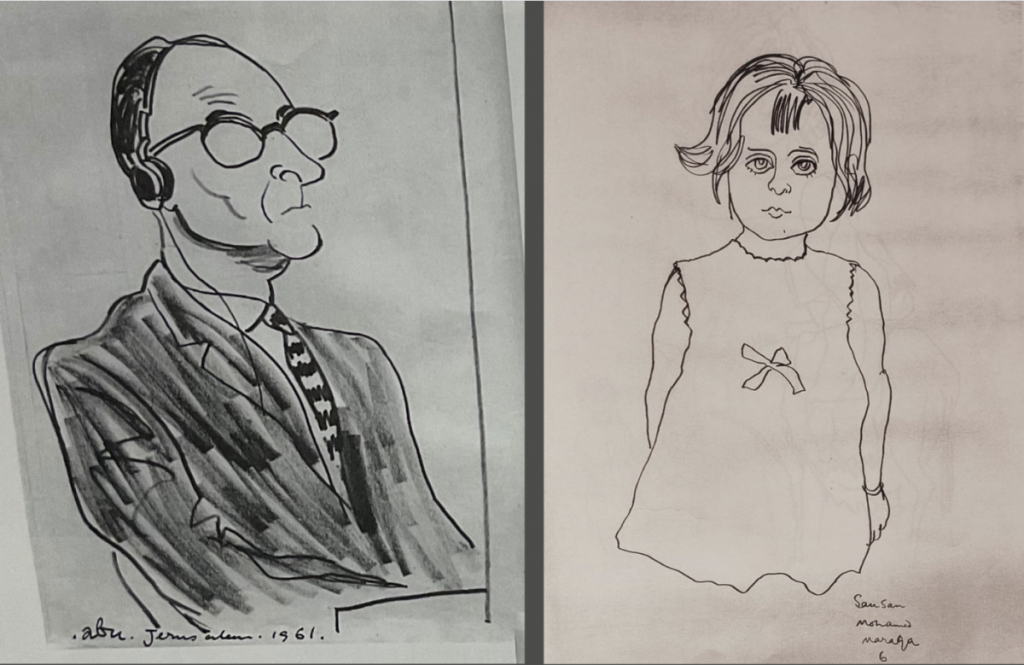

Among the sketchbooks that chronicle Abu’s many travels, two stand out – one on the Adolf Eichmann trial in Jerusalem in 1961, and the other on his visit to a Palestinian refugee camp run by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), in 1967. In the first sketchbook, Abu captures the Nazi in all his defiance and unrepentance, the judges going about their business, and witnesses and survivors awaiting justice. The second sketchbook effortlessly communicates the plight of innocent children and inconsolable old men at the Palestinian refugee camp desolately peering out of the frame, having lost their land, their homes, and all hope. Viewed together, these sketchbooks from the past serve as stark reminders of how human pain and misery engendered by the cycle of hate and violence continue to spill over into our present.

(Left) From Abu’s sketchbook chronicling his visit to Jerusalem in 1961: a sketch of an unrepentant Adolf Eichmann during his trial in Jerusalem. (Right) In 1967, Abu visited a Palestinian refugee camp run by the UNRWA. As usual, his sketchbook did the talking, as in this sketch of a child from the camp.

The Kerala Lalitha Kala Akademi deserves all praise for bringing this major cartoon exhibition to Abu’s native state for about a month on the occasion of his centenary year. With this show the Akademi moves beyond the conventional, constrained definitions of ‘art’; an important step if you seek to engage with a younger generation that is very much at home with the hybrid language of comic art. This exhibition should travel to other parts of the country as well – while being a memorable acknowledgement of Abu’s genius, it is equally a deserving celebration of the rich and glorious tradition of Indian newspaper cartooning.

Gokul Gopalakrishnan is a Kerala based cartoonist and comic art researcher.

This article went live on April twelfth, two thousand twenty four, at zero minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.