As the Gujarat Model Goes National, Hindutva Hunts for the 'Enemy in Our Midst'

This essay dates back to an earlier episode of the Hindutva march to majoritarian politics. Towards the end of the 20th century, Gujarat became the laboratory testing out the agenda set by the Sangh parivar under the high command of the RSS, which Narendra Modi had joined already at an early age. Published originally in a Dutch edition in 2003, I reported at close quarters on the onslaught in the working class quarters of Ahmedabad and elsewhere in the state.

What is currently going on in North India in particular brings up the underlying design operationalised in long trajectory which aims at splitting up the population nation-wide in the 'deserving' segments included in mainstream society and the 'undeserving' ones meant to remain deprived from citizenship rights and ghettoised in marginality.

Towards the end of the last century, Samuel Huntington described the new fault lines that have emerged in the global system since the collapse of the Soviet empire. In The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, this practitioner of geopolitics debunked the assumption that the end of the Cold War era heralded a period of growing international cohesion. He opposed the conclusion that the dwindling away of old fault lines had been accompanied by a transition to a world order based on peaceful cooperation. Liberal and left-wing critics of Huntington claimed that his analysis was founded on ‘enemy thinking’ with the aim of implying the existence of a threat. The fear he aroused was grounded in the expectation that pursuance of Western domination elsewhere in the world would generate fierce resistance. Huntington identified West Asia as the front where a clash was imminent. His analysis seemed to be only a few short steps ahead of events. But perhaps the clash of civilisations, presented by Huntington as a prediction, had already been incorporated in America’s geopolitical strategy.

From an Atlantic perspective, the emphasis indeed lay on the confrontation in West Asia. This is, after all, the centre of Islam, the religion condemned as anathema to progress and enlightenment. Those who adhere to this faith, we are told, have a tendency towards fundamentalism. They are also allegedly susceptible to calls to express their discontent, rooted in a misplaced feeling of repression, if not by committing terrorist acts then at least by empathising with them.

What this perspective on Islam fails to take into account is that the great majority of Muslims live far from the front lines of the clashing civilisations. Insufficient attention is given to the deprivation and persecution experienced by Muslims in countries where they form a minority. Besides rural areas of China (Xinjiang) and Russia (Chechnya), where they also differ in ethnicity from the inhabitants of the heartland, this discrimination also applies to India. Some 14.2% of the 1.2 billion people who live in this country are Muslim, giving it the world’s second largest Islamic population, after Indonesia. Their social position has witnessed a downward turn in recent years due to the emergence of a political party that aims to unite and solidify the Hindu majority of nearly 80% of the population by identifying Muslims as ‘the enemy in our midst’. Equipped with an identity considered alien to the majoritarian culture, the members of the Islamic minority stand suspected of anti-nationalistic sentiments.

Hindu revanchism

This demonisation of the Muslim community cannot of course be seen in isolation from the conflict with Pakistan. The partition of India in 1947 had its origins in differences between Muslims and Hindus, which had been exacerbated in the late-colonial era. The uneven spread of the two religions across South Asia suggested that a territorial division along lines of faith would be the obvious solution. But India’s political leadership emphasised its wish that the society that took shape after being liberated from colonial domination now half a century ago should be secular in nature. The constitution safeguarded freedom of religion for non-Hindus – Christians and Buddhists, as well as Muslims – and granted everyone the same civil rights, irrespective of caste, faith or race. Proponents of religious tolerance and cultural pluralism could fall back on a tradition in which Hinduism – unlike many other civilisations – was restrained in imposing its own religion on newcomers.

There is much at fault with this perspective, especially where recent history is concerned. Already before independence, a political movement emerged that considered it as its mission to give India, once it had been scourged of all foreign elements, an unadulterated Hindu identity. Mahatma Gandhi, who led the fight for independence, wished to leave scope for religious diversity, which was to cost him his life at the hands of an extremist Hindu assassin. Some decades later, the Bharat Janata Party (BJP) emerged from this same ambiance, preaching the religious and political domination of the majority. There is no place in this recast societal scenario for equal rights, or even tolerance towards the minority.

V.D. Savarkar, the founding father of the Hindutva movement, expressed his sympathies for the Nazi regime in Germany. His variant of the Nazi’s racial doctrine was to deny Muslims and Christians their civil rights. As their holy lands lay elsewhere, their external loyalties could only erode their loyalty to India. End February 2003, Savarkar’s portrait was unveiled by the President of India in the Central Hall of Parliament. It came to hang directly opposite that of Mahatma Gandhi, the father of the nation, who was murdered by a disciple of Savarkar shortly after independence.

The revival of the true religion, that of Bharat (the mother country), calls for rage and revenge for everything endured under centuries of Muslim domination. The arrival of Islam was accompanied by military occupation, with bands of warriors led by their princes invading the country, looting the Hindu heritage and building mosques where temples had stood.

All respect for and pride in Moghul architecture and art has disappeared. School textbooks have been rewritten to focus more expansively on outrages committed against the land and people. In this version of history, Muslims are portrayed as traitors to their original, true faith. The only reason not to brand them as defectors in retrospect is the suggestion that they may have been forced to convert to Islam. That explanation denies that conversion to the religion of the newcomers offered an escape from the discrimination and subjugation to which the lower castes were exposed in the Hindu hierarchy. Political Hinduism denies the distinction between high and low castes, just as it ignores the huge discrepancies between rich and poor. Unity at home takes priority. Ranks are closed by identifying the Other as an outsider, as a threat to the commonweal.

Leaders and members of the BJP and its front organisations claim to speak for all Hindus and respond fiercely to those who deny them that right. The non-believers in this call to supremacy – and there are fortunately a large number of them – feel this now dominant ideology lacks the cultural tolerance and social multiformity that they consider essential to civilisation. For them, syncretism, being a melting pot of diverse religions and traditions, is what gives civilisation meaning. Conversely, these critics – be they religious or secular – reject the tendency to see Muslims as a homogeneous community. The Muslim minority, after all, is made up of countless factions and displays great socioeconomic diversity. If supporters of Islam at home and abroad preach hatred or resort to terrorism, it should never mean that all Muslims are held collectively responsible.

The 2002 pogrom in Ahmedabad

On the train to Ahmedabad, with a population of 3.5 million the largest city in Gujarat, the man sitting next to me asks me where I am going. ‘It’s a lovely city’, he tells me, ‘but there are too many Muslims’. ‘But they’ve shown how to deal with that problem,’ says another passenger, laughing. I stay silent for the remaining 16 hours of the journey.

In 2002, I reported on the attacks on Muslims that started on February 28, 2002 and, in the days and weeks that followed, cost the lives of nearly two thousand men, women and children. Many tens of thousands were forced to flee to hastily set up camps to avoid the same fate. It was not my first report of a pogrom in the city. In 1992 there had been a similar ‘outburst of popular rage’; this is how the powers that be describe the Kristallnacht of horrific excesses that occurred at many sites in Gujarat. Official statements express condonation for the hatred shown towards the Muslim minority, which they blame for provoking the tolerant and peace-loving majority to commit these cleansing operations.

From this perspective, the 2002 pogrom was in response to the setting fire of a train full of Hindu pilgrims returning from Ayodhya on February 27 that year. Ayodhya is a pilgrimage site on the Ganges plain where the Babri masjid was demolished on December 6, 1992 to be replaced by a temple dedicated to the god Ram, who is believed to have been born there. After the train burning in Godhra, the authorities immediately issued a statement condemning it as a terrorist attack and alleging that the Pakistani government had been involved. Narendra Modi, then chief minister of the BJP government in Gujarat, told his party members and the associated front organisations that he could understand the wave of counter-violence that would inevitably follow the atrocity. Besides calling forth that violent response himself in forceful language, he also gave the perpetrators free rein by ensuring the victims would receive no protection from the government. If the police did take to the streets, it was to break the resistance of the victims and show the attackers where to find them. For many days, gangs swarmed through Muslim areas of the city, looting, starting fires and killing. Often, they would have lists of the addresses of Muslims and their properties. Reports by human rights organisations have found incontestable proof that politicians and government officials not only knew about the pogrom but also actively cooperated in it.

Inciting hatred

In the elections of mid-December 2002, Modi attained a new and much more substantial mandate than he already had. The spearhead of his campaign was the honour of Gujarat, which he claimed was being eroded by the enemy of the country and its people. The front man of Hindu fundamentalism left no room for misunderstanding as to who he considered this enemy to be: the religious minority in the homeland, who he contemptuously referred to as miyans. According to the Hindutva worldview, they bear no loyalty to the nation of which they are a part. Their ties to their fellow Muslims beyond the country’s borders makes them a fifth column out to undermine Bharat from within. All those who wish to do business with the enemy or call for reconciliation are just as complicit while, in BJP jargon, secular is a term of abuse. Modi wanted to generate hard confrontation.

The hatred that permeated Modi’s speeches then had various facets. First, Hindus must avenge the brutalities that they have suffered in the past. In this new doctrine, tolerance is nothing more than weakness on the part of former generations, their refusal to take a resolute stand against the longstanding domination of the Mughals. The rape of a large number of Muslim women and girls in 2002 was even justified by some with the argument that this unimaginable sexual predation was vengeance for abuses against previous generations of Hindu women. The hatred was fuelled even further by the belief that Muslims deliberately have more than the average number of children so as to increase their numerical strength. Lastly, hostility is incited by accusing non-Hindus of wanting to convert the majority to their faith. From the Hindutva perception, Hindus can only abandon their religion under coercion. They are guilty of treason against their faith but the anger of the faithful is directed primarily against those who force them to do so, not only Muslims but also Christians and Buddhists.

Anne Frank in Gujarat

In autumn 2002, an Anne Frank exhibition happened to be held in Ahmedabad. The state-supported pogrom was hardly over when the people of the city were confronted with the fate of a young Jewish girl in the Nazi era. In light of the witch hunt against the religious minority in the city, the story of Anne and her family hiding in the back room of a canal-side house in Amsterdam and its fateful conclusion came at a poignant moment.

I would like to have written that this initiative was a manifestation of a conscious Dutch cultural policy, to present the exhibition in the right place at the right time. But that would be far from the truth. The event was part of a multifaceted programme that had taken many years to prepare, entitled ‘400 Years Indo-Dutch Partnership’. The programme was intended to celebrate the fourth centenary of the establishment of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and of relations with India. When I was appointed as a member of the committee preparing the programme I noted that, to my knowledge, this was the first time that colonialism had been presented as a form of partnership. The Anne Frank exhibition was staged in a number of cities, but on arrival in Ahmedabad it of course acquired a significance that had not been foreseen. The message did not escape the visitors to the exhibition. One schoolgirl wrote in the visitors’ book ‘Narendra Modi should see this’.

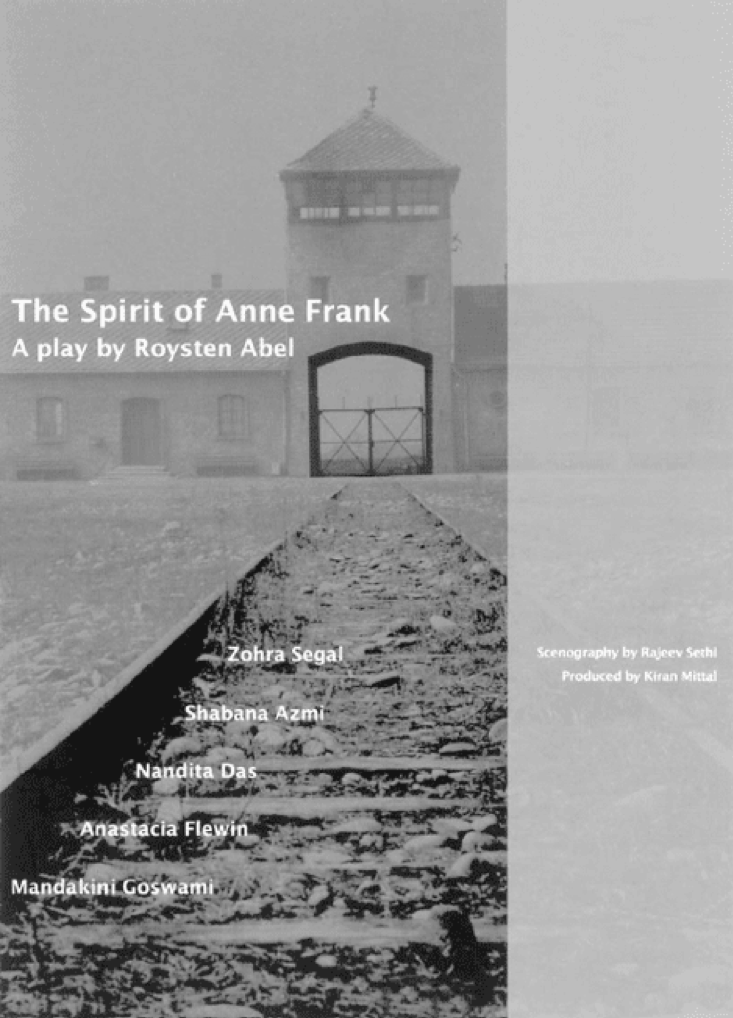

A cause of even greater friction with the government of Gujarat was the performance of The Spirit of Anne Frank, a play produced with the financial support and cooperation of the Dutch embassy. In early December 2002, I attended the première in a jam-packed theatre at the National School of Drama in Delhi. The play is an Indian production written by Roysten Abel and the programme booklet clearly depicts its subject matter: a railway line coming to an abrupt stop at the entrance to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland.

The Indian variant of the story of the Endlösung is about five women who share a train carriage on the way to Godhra in Gujarat. They all have names that refer to Anne. Each has a hidden past that is gradually revealed in the course of the journey. Two of the actresses, Shabana Azmi and Nandita Das, achieved popularity with the film Fire, in which they played a lesbian couple – a partnership never shown on the silver screen before in Bollywood. Breaking this taboo had earned them the hatred of Hindu fundamentalists. Their roles in this play would add fuel to the fire of displeasure already raging in these circles. The play ends when a mob stops the train, looking for members of the religious minority with the intention of killing them. The youngest of the four women, still only a girl, is terrified because what she has always learned to hide will now be revealed: her Muslim identity.

There was good reason to look forward with some trepidation to the performance of the play a week later in Ahmedabad. Even more so because it was to take place two days after the elections in Gujarat. The result, a landslide victory for Narendra Modi, was not yet definite but it was in the air. The authorities tried to get the performance cancelled, arguing that it was a potential threat to public order. The script had to be submitted to a censorship committee; as a precautionary measure, the director had already scrapped the name Godhra, the destination of the train in which the four main characters were travelling. It is the name of station where the train carrying kar sevaks had been set on fire on February 27, 2002. The performance went ahead, preceded by an announcement that if the behaviour of the audience called for it, the theatre would be evacuated immediately. At the end of the play, the actresses and the audience thanked each other in tears, a sign of just how high emotions were flowing.

The long-range remote control of Hindu nationalism

The stigmatisation of the religious minority in India has its roots in the call for the majority of the population to close ranks around what binds them together – their religion. Any differences that do exist must be subordinated to antagonism towards outsiders. I will return shortly to the forces within the Indian social order that underlie this. But the success of the fundamentalist Hindu revival cannot be understood without taking account of political forces acting from outside. The shifts that are taking place are related to changes at transnational level. The leaders of the Hindutva movement felt strengthened in their anti-Muslim sentiments by the change of course in US foreign policy after September 11, 2001, despite the clear elements of Christian fundamentalism in the latter. In India, there was only dissatisfaction at the fact that the US, in its search for evil – which focuses almost entirely on the world of Islam – was slow to take advantage of India’s offer for a closer alliance against the common enemy.

Also Read: Narendra Modi’s Reckless Politics Brings Mob Rule to New Delhi

But globalisation has facilitated another form of external involvement in the spread of Hindu nationalism. The feelings of hatred to which Modi owed his election victory in Gujarat in December 2002 did not represent a form of political capital that he tapped into unconsciously. They had been incited through a systematic campaign of indoctrination focused on segments of the Indian population settled abroad and previously neglected by BJP politicians. In the 1990s, the party’s front organisations amassed large sums of money to mobilise support among these expatriate communities. The lion’s share of these funds has been raised in North America and Europe. Non-Resident Indians, many of whom originate from Gujarat, have proven willing to donate to the cause to demonstrate their solidarity with the home front. These feelings of loyalty are strengthened by the uncomfortable pressure to integrate and adapt to the lifestyle of their host countries. This explains why the Dutch branch of Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) – a front organisation for Hindu fundamentalism which mainly recruits its members from Hindus from Suriname – urged its supporters in the Netherlands to vote for a populist politician in the Dutch elections. His description of Islam as a primitive civilisation was decisive in this advice, showing once again that, the process of obtaining Dutch citizenship strengthens newcomers’ feelings of solidarity with their country of origin. The pressure to adapt to the host country contributes to the emergence of new, transnationalised identities. When settling in the Netherlands, Hindus and Muslims from Suriname who previously lived in close proximity to each other find themselves split up and taking separate routes in their new lives.

Segregation a major feature of caste system

It is striking that after months of violence in the cities, towns and villages of Gujarat, there were no signs of distress or remorse among the Hindu majority. During repeated visits in the course of 2002, I heard everywhere I went that what had happened was long overdue. ‘These people’ had got what they deserved; now ‘they’ had to be kept under the thumb for good.

At the annual meeting of the RSS, the organisation's spokesman described with satisfaction how ‘the problem’ in Gujarat had been tackled. He added that Muslims had to understand that, if they wished to remain in the country, they were dependent on the goodwill of the Hindus. Victims of the violence received no compensation for the property they lost and were given no opportunity to give voice to the suffering they have endured. Hundreds of women and girls must have been raped during the 2002 pogrom in Ahmedabad, but there are no records of these incidents. Anyone who dared to report the atrocities was told by their attackers or even by the police that such accusations will result in even more horrific reprisals. And among themselves, Muslims also try to conceal the molestation of female relatives. There is implicit agreement not to inquire about what has happened to their neighbours, so as not to bring discredit to their own and the other family.

What dynamics in Indian society have led to the identification and expulsion of this enemy within? Hindu propaganda emphasises the Muslims’ refusal to act as a subordinate minority, the macho behaviour of Muslim men, unfair competition with Hindus on the tight labour market, their 'lack of loyalty' and a whole list of other defects attributed to them collectively. Those who oppose these stereotypes point to the cordial relations between Hindus and Muslims in the past, as friends, colleagues and neighbours who visited each others’ homes, exchanged gifts, shared food and were accepted into each others’ close family circles in good times and bad. I fear that this is an exaggerated portrayal of the degree of past closeness and confidence. Traditionally too, social contact was primarily limited to one’s own communal niche and the network around it.

Importantly, however, this applied equally to the dividing lines within the Hindu community, which were based on the principle of inequality underlying the social structure. High castes kept the lower castes at a distance, also in a literal sense. The twice-born accepted no food from the common people, and throughout the whole hierarchy the castes operated as closed groups that looked more inwards than outwards. At the bottom of the ladder was a layer of people who were so 'untouchable' that all contact with them had to be avoided. There is a well-known story in Gujarat about an 'untouchable' saint who sacrificed himself to lighten the burden of his fellow caste members when a human life was required to bring a long period of drought to an end. The upper caste ruler in the area rewarded the 'untouchables' for this sacrifice by no longer obliging them to wear a broom on their backs to clean the path for those who walked behind them. Fear of temporary or even permanent infection resulted in many such excessive forms of avoidance in everyday life.

The new 'untouchables'

Since independence Indian society has undergone far-reaching changes. In my summary description of these changes, my main conclusion is that, for the large majority of the population, caste has remained a major focal point. The rules of the caste system specify how men, women and children should behave, and marriages continue to be arranged predominantly within families’ own social milieu. In as much as there is a break with the past, it largely relates to changes in perception of the relationship between high and low, to a transformation of a caste system in which the former ideology of deep-seated inequality has waned. The former high-low segmentation of superiority versus inferiority tends to give way to a social structuring along vertical lines, a kind of next-to-each-other pillarisation. That process has not been completed but is a trend that is discernible throughout the social system. Brahmans no longer find general acceptance for their claims of supremacy in the caste order, while the 'untouchables' – who now call themselves Dalits – refuse to accept the stigma of abasement imposed upon them. But the greatest shifts are taking place in the broad middle segment of society. Material progress is expressed in the adoption of a ‘purified’ lifestyle based on the customs and practices of the higher castes, which were previously beyond reach. Women are no longer permitted to go out to manual and strenuous work but are confined to the home. Increased piety, as shown by regular temple attendance or membership of an orthodox sect, is also an expression of newly acquired status. Consequently, a mood and practice of growing Hinduism can be observed in more and more communities. What began as a cultural phenomenon has now been translated into a political programme.

Also Read: From Jan Breman, a Treasure Trove of Essential Analysis on Labour, Bondage and Capitalism

Hindu nationalism has particularly taken root among higher castes. This social elite has always been very influential, but its limited size prevented it from translating that influence into political power. India is after all a democracy in which every vote counts. The majority of the population comes from the lower castes who, because of the state of subjugation in which they lived and the disdain to contempt with which they were treated by the upper castes, did not easily vote for a party propagating a militant-orthodox regime. To win the support of this broad mass of the population, the BJP’s strategists therefore initiated a radical change of course. People who only a few decades ago were refused access to temples and were exposed to all kinds of extreme discrimination were now told that ‘in this modern age’ they were entitled as Hindus to the same rights as were formerly reserved only for members of the higher castes. Their admittance to the faith – though still not to high-caste temples - unavoidably coincided with improvements in their social position. Those who were seen as untouchable in the ideology of the caste system have become touchable as voters. This call for a homogenising Hindu awareness undoubtedly conceals a hidden reality that remains far from the promised equality. But this does nothing to change the fact that political propaganda passionately propagates the unity of all Hindus.

To ensure the ranks remain closed, it is necessary to identify outsiders who are neither willing nor able to share in the awareness of the Hindu nation. These are the Muslims and secular ‘unbelievers’ who fall outside society because there is no place for them within it. In Hindutva ideology, they have become a class of untouchables. The hatred previously reserved for the 'untouchables' has now been projected on them. The Hindu 'untouchables' themselves of course have to pay a price for their new 'dignity'. The violence needed to keep the Other outside the door has been entrusted to those who traditionally found themselves at the bottom of the caste system. Consequently, the Dalits – the ‘oppressed’ – were over-represented in the mobs attacking the Muslims on the streets of Ahmedabad during the pogrom of 2002.

A test case to be followed?

The Muslims have been excluded from the social system in more ways than one. In the first place by expelling them from their homes and neighbourhoods, with the result that ghettos have been formed on the margins of the city. I covered this in detail in an essay published eleven years ago. Secondly, there are repeated calls for an economic boycott. Pamphlets were distributed in ‘good neighbourhoods’ in Ahmedabad calling on people not to do business with Muslim shops, not work for or employ Muslims, and to avoid all social contact with them. Mixed marriages are completely out of the question. For those that have already taken place, especially for Hindu women, the only solution is to annul the marriage. These guidelines outline a manual for demoting Muslims to the status of second-rate citizens.

A concern at the time was what impact would Hindu revanchism in Gujarat have on national politics. The BJP’s leaders were initially concerned about the extremist course adopted in the state. During foreign visits, the then prime minister, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, was so embarrassed by questions about the state of affairs in Gujarat that he felt obliged to apologise, though he did not specify in detail what he was apologising for. After Modi’s resounding victory in the 2002 elections, however, the mood changed. In other parts of India, where the BJP was not doing so well, the reasoning now was that if deliberately aggravating divisions has benefited the BJP in its Gujarat laboratory, it might be the formula it needs to turn the political tide. Modi went on tour presenting his approach as the only correct strategy.

The state-supported pogrom in Gujarat caused a shockwave beyond the state’s borders. Many commentaries draw parallels with Germany in the early 1930s. There were clear similarities, but the comparison did not – and does not – do justice to the complexity of social dynamics in India, including those in the multifaceted Hindu community, that resist the identification of Muslims as the country’s new untouchables. The comparison with the emergence of Nazism and fascism in Europe three-quarters of a century ago is perhaps less appropriate than with the hard-handed oppression of Palestinians currently being practised in Israel by Benjamin Netanyahu, or with the Russian leadership’s ‘solution’ to the issue of Chechnya.

In India, where freedom of expression still commands respect, there is no lack of authoritative voices calling for the secular structure of society to be preserved, including the associated separation of religion and state, exclusionary identity as against shared citizenship. The democratic nature of a political system is jeopardised if part of the population is denied rights and privileges because it adheres to a ‘deviant’ faith, with the aim of justifying their social exclusion. Against the background of the vilification of Islam, which seems to be an increasingly global phenomenon, that should be sufficient reason to follow the political situation in South Asia very closely.

Jan Breman is honorary fellow of the Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. He is the author of many scholarly works on Gujarat and India. His latest book, Capitalism, Inequality and Labour in India, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2020.

This article went live on March fifth, two thousand twenty, at thirteen minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.