At Krebs Biochemicals, a Snapshot of the Worm at the Core of the Pharma Apple

Amravati/New Delhi: Corporate misgovernance, attempts at allegedly influencing a judge, illegal manufacturing of life-saving drugs – a publicly-listed Andhra Pradesh-based firm has become the site of the many ills that continue to dog the Indian pharmaceutical sector.

Krebs Biochemicals & Industries, the company that finds itself in legal crosshairs, was established in 1991 and counts bigger pharma firm IPCA Laboratories as a significant shareholder (49.65% stake as of June 2022).

The pharma company – headquartered in Visakhapatnam, with manufacturing plants in Nellore and Vizag – is a contract manufacturer for large pharmaceutical companies and develops products for sale in global markets.

Over the last 15 years, Krebs Biochemicals’s run-in with Andhra Pradesh state drug inspectors has become a sordid tale of corporate misconduct, with multiple lessons for the regulatory ecosystem and India Inc.

Trouble started in September 2008, when AP’s local drug inspectors accused the company of violating Section 18 (c) of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940, which deals with the manufacturing, sale, distribution or stocking of drugs or cosmetics without a valid licence.

After a lengthy spell of litigation before the additional judicial magistrate (AJM), Kovur, Krebs Biochemicals and the-then managing director R.T. Ravi were found guilty of manufacturing five drugs without a valid licence and doing so while a stop production order was in force.

Ravi – who is currently the board's chairperson, having given the MD role to his son in 2015 – was sentenced to undergo rigorous imprisonment for one year and was ordered to pay a fine of Rs 10,000. The company was also fined Rs 10,000.

Krebs Biochemicals and Ranbaxy by The Wire on Scribd

Question of disclosure?

The judgment was delivered on March 26, 2019. In such a situation, it is only par for the course for a listed company like Krebs Biochemicals to disclose materially important information such as the conviction of its current chairperson to market regulator SEBI and the stock exchanges.

As per Para 5(3) of the company’s disclosure policy, an event, transaction or information shall be considered as material if, “The omission of an event, transaction or information is likely to result in a significant market reaction if the said omission came to light at a later date; or as per Para 5(7) …there would (be) any direct or indirect impact on the reputation of the Company.” Thus, the conviction should have been disclosed immediately to the stock exchange.

And yet, it’s not clear if this was done. The Wire examined the corporate filings of Krebs Biochemicals from FY’19 (available here on BSE and here on NSE), but could not find any disclosure or filing admitting the conviction of its current chairperson.

When The Wire reached out to Krebs Biochemicals on June 27, 2022 with a comprehensive questionnaire – asking specifically whether these disclosures were made, and if so where they could be found – we were told by company secretary and compliance officer Taruni Banda that she would pass on the queries to the firm’s top management. The Wire has yet to receive a reply to our questions, a copy of which can be found at the end of this story. This story will be updated if the company responds with a link to any disclosure made on any platform.

A separate e-mail sent to independent board director Venkata Lakshmi Prasad Gundapaneni on August 4, 2022 was acknowledged, with Gundapaneni saying he had forwarded the queries to the company's management.

It’s not as if shareholders were unaware of the pending litigation: a letter for offer issued by the company in February 2019 (one month before the guilty verdict) listed the probe as an outstanding criminal case.

“[Conviction of managing director is] definitely a material event that ought to have been immediately disclosed to the stock exchange since there is a risk that he may not be able to perform his duties and that may affect the company’s performance. Even if an appeal is filed subsequently and the conviction is stayed, that should also then be notified,” Murali Neelakantan, a former global general counsel at Cipla and Glenmark, told The Wire.

On top of this, it’s also unclear if Krebs disclosed to the regulator, and its investors, that it had been convicted for manufacturing and selling drugs without a licence. Neelakantan pointed out to The Wire that such a development is also a material event since it is fundamental to the company’s business.

On appeal, allegation of influencing a judgment?

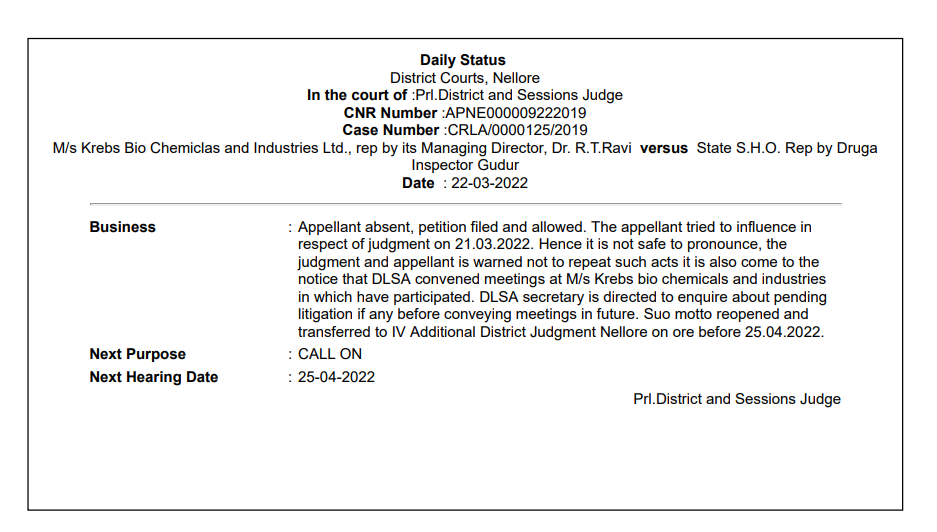

The legal saga only gets worse, though. The case went through the appeal process and on March 22, 2022, the principal district and sessions judge accused the company of trying to “influence in respect of judgment”.

"The appellant tried to influence in respect of judgment on March 21, 2022. Hence it is not safe to pronounce," the principal district and session judge observed.

He warned the appellant not to repeat such acts and the case was transferred to one of the additional district judges.

How did Krebs Biochemical land in a legal soup?

As the appeal winds its way through the judicial system, it is useful to remember what exactly Krebs is under fire for.

Kovur AJM Shaik Pedakhasim found the company and Ravi guilty on eight counts under Section 18 of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940.

The court found that Krebs manufactured a drug called Pseudoephedrine Ep/Ph without obtaining any licence to do so from the local drug control administration in Hyderabad. The prosecution, that is the state of Andhra Pradesh through its Gundur drug inspector, presented 10 sale invoices that the company had provided the drug control administration officials during the course of the investigation, to the court. The drug is used to treat nasal congestion.

The court also found that Krebs, along with Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited, manufactured and sold a drug called emtricitabine even after its 'test licence' had expired. (A test licence is a special licence granted as per Rule 89 of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act. Unlike the usual manufacturing licence, this licence grants permission for making drugs for test and analysis purposes).

The drug administration had granted the company the test licence for a year starting from May 15, 2007. But during the course of the investigation, officials found that the company had produced it in huge quantities – 51.2 kg – after the licence had expired for 22 days starting June 23, 2008. The judge said the evidence was unambiguous about the violation as the company was not granted any fresh or extension of the existing licence.

Furthermore, the company even indulged in manufacturing drugs without obtaining a test licence at all. It was at a much later stage that it actually got a test licence. The prosecution established in court that Krebs produced as much as 495.85 kgs of a drug called atazanavir sulphate from March-May 2008 while the licence was granted to it in June 2008. The drug is used in the treatment of AIDS patients. Termed an 'antiretroviral' drug, it prevents the HIV virus from replicating inside the body. This drug is consumed in combination with other anti-HIV drugs. The court labelled it as a 'highly potent' drug.

The same nature of allegation was levelled against the company for lopinavir, another 'antiretroviral' drug used by AIDS patients. Before the drug administration had granted a test licence for one year on January 3, 2007, the company had manufactured 117.965 kg of the bulk drug from July-September 2006. The prosecution produced various records to this effect which the court found irrefutable.

Tadalafil kerfuffle

Krebs also became a 'licensee' for Ranbaxy to make another drug, tadalafil. The latter was granted a loan licence for the drug by the Drug Control Administration, Hyderabad, on February 5, 2008.

Tadalafil is used for correcting male erectile dysfunction.

Section 138 (a) of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act defines a loan licence thus: A licensing authority may issue [licence] to an applicant who does not have his own arrangements to manufacture but who intends to avail himself of the manufacturing facilities owned by a licensee.

The licensee's premises are inspected by the drug control administration to see if it has adequate equipment, staff and resources to manufacture the drug. The licensee, in this case, was Krebs Biochemicals which was taken on board by Ranbaxy. (Ranbaxy, in this case, was the one which actually applied for the loan licence.)

The court found Krebs started manufacturing the drug in collaboration with Ranbaxy even before the loan licence was granted. The investigators found that it had made 37.2 kg of drug till January 29, 2008 – almost a week before obtaining the loan licence. The authorities discovered this in their investigation in in September 2008.

Krebs tried to argue in the court that it had manufactured all these drugs in "small quantity", and for research and development needs.Therefore, it said, a licence was not required. The court rejected both the arguments. It said the quantity was actually quite huge and its use was not limited strictly to research and development purposes. Insofar as the second argument was concerned, the court said Rules 89 of the Drugs and Cosmetic Rules clearly say even for test and examination purposes, a licence was needed.

"If really the version Accused 1 (A1) and Accused 2 (A2) – Krebs and its managing director Ravi – that they can manufacture drug without licence as same is small quantity or same is for examination, test or analysis purpose is lawful there is no need for them to obtain licences," the court said in the judgment and wondered why they had applied for licences at a later stage if there was no need for them in the first place.

The Hyderabad Drug Control Administration said in court that at the time of inspection its officials found that none of the approved manufacturing chemists were available on the premises when such "potent drugs" had to be produced under the "personal supervision of an experienced person only."

The court also found that the company had purchased pseudoephedrine hydrochloride from another company, Avon Organs Ltd. Krebs only had a licence to export that drug as per US pharmacopoeia grade standards. Instead, it relabelled the same drug and sold it to Indian drugmaker Cipla Ltd at its Goa unit, thus, again violating Section 18(c) of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act.

Not only that, Krebs continued to manufacture this drug when the drug control administration issued a 'stop production' notice to it. From October 3, 2008, the officials asked the company to halt the manufacture till February 5, 2009. But in this time period, Krebs produced 2000 kg of drug.

The company tried to argue in court that its directors couldn't be solely held liable for the allegations. They cited various previous judgments of high courts and the Supreme Court to that effect. But the Kovur court was not impressed.

"In view of the above facts [presented in court], circumstances and other material on record, this court is of the opinion that the prosecution proved its case against the accused no.1 [Krebs Biochemicals] and 2 [RT Ravi] for the charged offence beyond all reasonable doubt,” the judgment reads.

"It cannot be said that staff of A1 company manufactured drugs without a valid licence and without directions from [the] Managing Director or Board of Directors," the court said.

"If the drug is substandard same can be attributed to the technical staff as Managing Director cannot look into each and every aspect in the manufacturing place and in the manufacturing process as he has to attend several duties, but coming to the aspect whether a particular drug can be manufactured or not is the policy decision/matter for which Board of Directors or Managing Director are responsible," the court added.

Questions that The Wire sent to Krebs Biochemicals:

1. Has the conviction of Dr R T Ravi been disclosed under the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015? Our examination of stock exchange filings indicate that there has been no disclosure to this effect. Please let us know if a disclosure has been made to SEBI conveying the conviction of Dr R T Ravi by the judgment dated March 26th, 2019. And, if no such disclosure has been made, why does the company believe this is information that does not require disclosure?

2. Section 164 of the Companies Act, 2013 states that no person shall be a director of a company if he has been convicted of an offence and has been sentenced to imprisonment for a period not less than six months. Going by this provision, Dr R T Ravi should have been disqualified from being appointed as a director. As this is obviously not the case, what is the company's and Mr Gundapaneni's position on this legal issue?

3. In an order dated March 22, 2022, the Principal District and Sessions Judge, Nellore in case number CRLA/0000125/2019 has observed that the appellant, that is, Krebs Biochemicals and Industries Private limited represented by Dr R T Ravi attempted to influence the judgment to be delivered by the said judge. What kind of "influencing" did Krebs or its management try to do? What does the firm have to say for itself in response to the court's judgment?

This article went live on August ninth, two thousand twenty two, at zero minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.