Behind Sikkim's Firm Aversion to a Darjeeling Merger Is Two Centuries of Politics

Darjeeling: The otherwise peaceful town of Namchi in the South district of Sikkim was witness to sudden unrest recently when, defying stringent pandemic restrictions, youngsters torched the effigy of a Gorkha Rashtriya Congress (GRC) leader.

Sixteen people were arrested for the demonstration and charged under various sections of the Indian Penal Code along with the Disaster Management Act.

Ramesh Rai, who had led the protests, said later, “I appeal to the people of Sikkim to stand up against the ploy to merge Darjeeling with Sikkim. We support the demand of Gorkhaland, however, we will never allow the merger.”

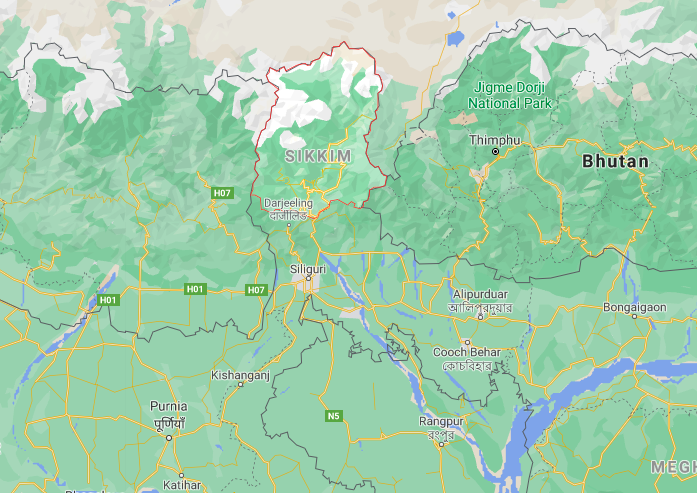

Darjeeling is a district in West Bengal, bordering Sikkim on the south.

Sikkim and Darjeeling. Photo: Google Maps

While the GRC, a political outfit from Darjeeling, has been urging Sikkim to reclaim its 'lost territory' in Darjeeling, Sikkim has been opposing it. The ruling Sikkim Krantikari Morcha-Bharatiya Janata Party alliance, to the opposition Sikkim Democratic Front and even the general public are united against attempts to merge the Darjeeling tract with Sikkim.

This is the first time that this demand is facing such strong opposition in Sikkim.

The Kingdom of Sikkim was founded by the Namgyal dynasty in the 17th century. In 1974, Sikkim was made an associate state of India. In 1975, a special referendum was held in Sikkim and 97% of the electorate voted for its merger with India.

Finally, on May 16, 1975, an amendment to the constitution paved way for the Himalayan kingdom to become the 22nd state of India. This state of Sikkim was accorded special constitutional status under Article 371F to preserve, protect and safeguard the identity, interests and rights of the people.

The reading down of Article 370 for Jammu and Kashmir could have led to anxiety in Sikkim as people fear Article 371F could be diluted in case a merger takes place.

The GRC and the Sikkim Darjeeling Merger Forum (SDMF), both based in Darjeeling, demand that the Darjeeling district – which was originally a part of Sikkim – be merged with the state.

They claim that the merger would make Sikkim a bigger and more viable state, along with fulfilling the age-old aspiration of the people of the Darjeeling Hills to separate from Bengal.

As the topography, geography, culture, language and socio-economic structure of both regions are the same, a merger is the logical option, feels the GRC.

Also read: Can Bimal Gurung Change the Equations in Bengal’s Himalayan Foothills?

Resurrection of the merger demand

During the weeklong visit of West Bengal governor Jagdeep Dhankhar to the Darjeeling Hills in the last week of June, a GRC delegation had submitted a memorandum to him. The memorandum states that the Gorkhas have been struggling for self-rule or separation from Bengal for long.

Several other organizations as well expressed concern at lack of grass root democracy #GTA area for two decades.

Lack of audit breeds corruption and ignores governance transparency and accountability @MamataOfficial

Administrator #GTA directed to brief me on all issues. pic.twitter.com/KksuLpuAL6

— Governor West Bengal Jagdeep Dhankhar (@jdhankhar1) June 26, 2021

"Bengal has no political and ethical right to oppose the unification, as the Government of West Bengal has published a White Paper in which it is clearly stated that this land belongs to Sikkim," claimed the memorandum. This White Paper or 'information document', published during the Gorkhaland agitation in 1986, is brought up often in this argument with some parties opposing its findings and some others endorsing it.

“The present territory of Darjeeling historically belonged to Sikkim and Bhutan and were included in India following wars with these two countries. Only the Terai part of the territory was for a time conquered by Nepal from Sikkim, but was returned to Sikkim in 1816, long before the District of Darjeeling took shape..," the paper states.

While the West Bengal government opposes the creation of a North Bengal state or Union Territory it cannot oppose the merger as there is "ample documentary evidence" that the Darjeeling district was and is an integral part of Sikkim, the GRC has said.

“The government of West Bengal’s White Paper clearly states that this land does not belong to them. They have admitted that it belongs to Sikkim,” repeated Subodh Pakhrin, chief coordinator of the GRC, talking to The Wire.

Pakhrin blamed the West Bengal government for not conceding to the Gorkhaland demand, despite agitations, loss of life and property. “This is because any party that is in power in Bengal reaps rich electoral dividends by opposing Gorkhaland. Whichever party comes to power in the state will never agree to carve out Gorkhaland,” said Pakhrin.

Pakhrin does not give credence to Sikkim's lack of interest and distinct opposition in "taking back" Darjeeling.

“Sikkim says it doesn't want to take back what was gifted to the British. Where is the question of a gift?” asked Pakhrin.

On February 1, 1835, a Deed of Grant was inked between the Raja of Sikkim and the East India Company. Through this, Sikkim handed over a strip of hill territory, 24 miles long and 5 to 6 miles wide which included present day Darjeeling and Kurseong. In return the Raja received an allowance of Rs 3,000 per annum. This amount was later increased to Rs 6,000 per annum.

Since 1950, Sikkim had been receiving Rs 3 lakhs annually.

Pakhrin stated that the GRC is in possession of documents that show that in 1963, one Ongden Lepcha, a member of the Sikkim Council had proposed that the Treaty Grant (the annual payment that Sikkim was receiving for Darjeeling since the signing of the Deed of Grant) be increased as Darjeeling’s source of income had increased at that time.

Pakhrin also stated that immediately after the merger of Sikkim with the Indian Union, a question had been raised in parliament regarding the status of Darjeeling. However, replying to this, then prime minister Indira Gandhi had stated that there has been no demand from any responsible quarters of Sikkim laying claim over the Darjeeling District. “Mrs Gandhi’s statement can be found in the parliamentary proceedings,” added Pakhrin.

He feels that a fear dominates Sikkim that resources will be disproportionately divided with the more populated Darjeeling in case of a merger.

Sikkim is spread over an area of 7,096 square kilometres with a population of around 7 lakh. The Darjeeling district has an area of 3,149 square kilometres with a population of 19.6 lakh. Kalimpong district has an area of 1,053.60 square kilometres and a population of 2.6 lakhs.

Article 371F

Ever since the dilution of Article 370 and the reorganisation of Jammu and Kashmir, Sikkim has been harbouring fears that Article 371F could face the same fate.

Women shout slogans during a protest in Kashmir after the reading down of Article 370. Photo: Reuters

“Article 371F grants special status and protection to Sikkim and her people. It is also the main instrument for the existence of Sikkim as an Indian state. Those who are raising the issue of Gorkhaland are doing so as per their constitutional rights. However, there is no question of Darjeeling’s merger with Sikkim. We vehemently oppose any such move,” stated Sikkim chief minister Prem Singh Tamang, popular as 'P.S. Golay.'

The ruling Sikkim Krantikari Morcha, which Golay founded, is not willing to buy the merger theory either. “It is neither being raised by the people of Darjeeling or any elected public representative or the government of West Bengal. We had opposed the issue when we were in the opposition bench and will continue doing so as long as the party is in power in Sikkim” said Jacob Khaling, spokesperson of the SKM.

SKM’s ally, the BJP harbours similar sentiments. “Sikkim and Darjeeling are unique. The constitution of India demarcates them as different entities,” stated D.B. Chauhan, BJP Sikkim president.

Former Indian football captain turned politician Bhaichung Bhutia, speaking to The Wire, expressed fears that the demand will open a can of worms.

“Sikkim is a border state surrounded by China, Nepal and Bhutan. This is a very sensitive issue. The people of Sikkim have made it clear that there is no question of a merger. We have our own laws and protection under 371F. This will be diluted. What happens to Kalimpong? Does it go back to Bhutan?” questioned Bhutia, who had floated the Hamro Sikkim political party in April 2018 and is currently the working president of the party.

Professor Mahindra P. Lama of the Jawaharlal Nehru Institute argues that the merger issue will dislocate the Gorkhaland demand at this critical juncture.

Talking to The Wire, Lama stated “There is competitive rivalry between the West Bengal government and the Centre over the Hills. Darjeeling stands to gain much politically at this juncture. Darjeeling does not want separation to merge with another state. Each has a distinctive culture and political history. Sikkim and Darjeeling are two parallels that will never converge.”

Also read: BJP To Divide Bengal? Only on Our Terms, Say Leaders of 3 Identity-Based Movements

'Uprooting Sikkim for Darjeeling'

Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) stated that while Sikkim supports Darjeeling’s quest for a permanent political solution in the form of a separate state, it in no way supports a merger. “Sikkim will be weakened with the merger. We cannot uproot Sikkim to provide a panacea for Darjeeling” said SDF spokesperson M.K. Subba.

While in power, SDF president and the then Sikkim Chief Minister Pawan Chamling, had moved a resolution in the Sikkim Legislative Assembly in March 2011 in support of Gorkhaland. However many are of the opinion that Chamling’s move in support of Gorkhaland was just an attempt to put the lid on the merger issue.

Earlier demands

In the past also the merger issue has surfaced especially in the backdrop of separate state agitations in the Hills. Time and again, prominent Hill leaders have resorted to the demand.

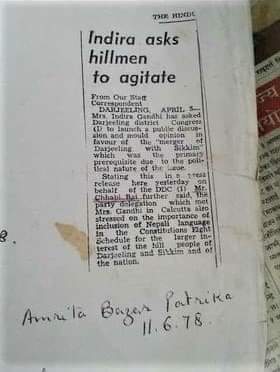

A news report from 1978.

In 1978 the Darjeeling District Congress Committee raised the demand of separation from Bengal and merger with Sikkim. Newspaper reports state that Indira Gandhi had then advised a Congress delegation to “initiate a public discussion and generate public opinion in favour of the merger of Darjeeling with Sikkim which is the primary prerogative due to the political nature of the issue.”

Addressing a gathering on October 7, 2015, at the raising day commemorations of the Gorkha Janmukti Morcha, its president Bimal Gurung, had stated, “No matter what, we want separation from Bengal. If the Union government is finding it difficult to carve out Gorkhaland from West Bengal then they should consider a merger of Darjeeling with Sikkim, as Darjeeling was initially a part of Sikkim."

The Communist Party of Revolutionary Marxist (a breakaway faction of the CPI-M) has also echoed similar sentiments. The CPRM feels that there is an urgent need for the Second State Reorganisation Commission.

“Provisions including breaking away parts of a large state and merging with other states are in Article 3 of the Indian constitution. The second SRC should be formed immediately and seriously consider the merger of this region with Sikkim," stated R.B. Rai, president of the CPRM.

All India Gorkha League leader the late Madan Tamang used to cite the example of Purulia in support of a merger. “Just like the region of Purulia was broken away from Bihar and merged with West Bengal in 1956 as it comprised mainly a Bengali speaking population, similarly the Darjeeling district and Dooars should be merged with Sikkim. We don’t see any difficulty in this merger” he used to state.

All the propagators of this theory cite its roots in the history of Darjeeling.

History of Darjeeling

In his book Darjeeling, Past and Present, (published in 1916,) E.C. Dozey writes that prior to the year 1816 the whole of the territory known as British Sikkim belonged to Nepal , which had won it by conquest from the Sikkimese.

“Owing to a disagreement over the frontier policy of the Gurkhas, war was declared towards the close of 1813 by the British, and two campaigns followed in the second of which they were defeated by General Ochterlony. By a treaty signed at Segoulie at the end of 1816 the Nepalese ceded the 4000 square miles of territory, which in turn by a treaty signed at Titaliya on February 10, 1817, handed over to the Rajah of Sikkim,“ states the book.

Photo: www.darjeeling.gov.in/history

In 1828, Captain G.A. Lloyd and civil servant J.W. Grant, the Commercial Resident at Malda, arrived at Chungtong, to the west of Darjeeling. “They were much impressed with the possibilities of the station as a sanitarium,” writes Dozey in the book. This was followed by another visit by Grant and J.D. Herbert, the then Deputy Surveyor General of Bengal.

The Court of Directors of the East India Company accordingly directed that Lloyd be deputed to start negotiations with the Sikkim Raj for the cession of the hill for money or land.

The transfer was successfully accomplished on February 1, 1835. The Raja of Sikkim handed over the strip of hill territory including Darjeeling and Kurseong, “as a mark of friendship for the Governor-General (Lord William Bentick) for the establishment of a Sanitarium for the invalid servants of the East India Company.”

In return, as mentioned before, the Raja received an allowance. “This exchange, however, considered at that time from a financial point of view, was entirely in favour of the giver...,” writes Dozey.

However peace was short lived. In November 1849, Sir (Dr.) Joseph Dalton Hooker, the famous botanist and Dr. Campbell, first Superintendent of Darjeeling while travelling in Sikkim, were arrested and imprisoned with the permission of the Raja. They were then severely tortured. A military expedition was launched by the British to free the duo in February 1850. This led to the withdrawal of allowance as well as the annexation of the whole of the district of Darjeeling which included an area of 640 square miles.

The British led another military expedition in February 1861. In March 9, that year, the British entered Tumlong, the then capital of Sikkim near Namchi. The final treaty was signed by the 80-year-old Raja on March 28. The Raja had to pay an indemnity of Rs 7,000.

The Daling sub-division with Kalimpong as the head quarter, bound by the rivers Teesta in the west and Jaldhaka in the east together with Bengal and Assam Duars, was annexed from Bhutan on November 11, 1865 and included in the district of Darjeeling, thereby increasing the area from 640 to 1,164 square miles, states the book.

The GRC has demanded that the Kalimpong district also be merged. However, present day Kalimpong was part of the Kingdom of Bhutan and was ceded to the British empire through the Treaty of Sinchula in 1865. The GRC argues that these areas originally belonged to Sikkim and were annexed to the Kingdom of Bhutan through wars between Sikkim and Bhutan.

This article went live on July fifteenth, two thousand twenty one, at twenty minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.