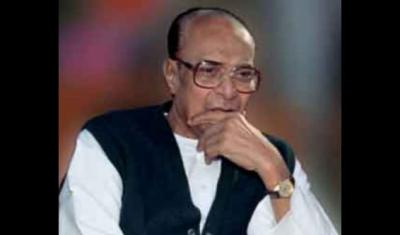

Biju Patnaik was a towering personality, towering literally and metaphorically over his contemporaries. He was – and still is – the only person in India whose body was wrapped in the national flag of three countries: India, Russia and Indonesia.

Mahatma Gandhi’s freedom struggle profoundly influenced him. He often sheltered revolutionaries in his house. Although commissioned into the Royal Indian Air Force in the early 1940s, he ferried secret messages and flew missions carrying political luminaries like Jayaprakash Narayan, Ram Manohar Lohia and Aruna Asaf Ali incognito. During World War II, he supplied arms and victuals to the desperate Soviet army struggling against Hitler’s army. He rescued Indonesian freedom fighters – Vice-President Mohamed Hatta and former PM Sutan Sjahrir – when Dutch imperialists chased him. He force-landed his aircraft on a Java paddy field feinting the Dutch, waiting before taking off and bringing them to safety in Delhi. A grateful Indonesia conferred honorary citizenship and awarded Biju the Bhumi Putra, a rare recognition for a foreigner.

Less known is that during his two-year-and-bit stint, 1961-63, as chief minister of Odisha, his was a monumental stack of achievements: Paradip Port, Sunabeda HAL factory, Barbil Iron Works, Rourkela Steel Plant, Talcher Thermal Power and Balimela Hydro Power Projects.

Far less known is that Odisha under Biju was the first state to streamline the Panchayati Raj and local self-government institutions towards democratic participation and not a cohort of elites or few armchair intellectuals. Reserving 33% seats for women in Panchayati Raj institutions during his second spell (1990-95) as chief minister, he emerged a pioneer. His message was implemented in the 73rd Constitution Amendment Act of 1992.

Biju’s speech in Odisha Legislative Assembly on November 20, 1961 is an invaluable document on Panchayati Raj. “We, from this house by our own judgment, are creating a child, a new democratic child, with the hope that with the growth of this child it would… develop… leadership which our people need—the leadership of execution,” he said.

Biju lived and breathed aspirations of the common man. “We are on the threshold of a very great experiment, perhaps the last experiment whether we can trust our people or not, whether our people with proper guidance and assistance can prove to be more efficient collectively than our present administrative apparatus.” Committed to democratic decentralisation which aims at making democracy real by ‘bringing millions into the functioning of their representative government at the lowest level’, he advised that far from hampering their functioning, “I heartily welcome the… Panchayati Samiti and Zilla Parishad”. It’s a “people’s movement.”

Panchayati Raj institution was introduced in 1961. But he didn’t rest easy. He wanted value-addition for rural poverty alleviation – and conceived an innovative scheme for agriculture-based small industries in rural areas. The Panchayat Industries scheme was Biju’s brainchild. Within a year, seven sugar mills, 20 tile-making units, ten carpentry units, ten small foundries, a paper mill and factories based on agricultural products were established. Panchayat Industries at grassroots levels earned kudos from Chester Bowles, then US ambassador to India, in his book The Makings of a Just Society. He wrote that if the scheme had been properly implemented, Odisha would’ve achieved industrial excellence like Japan. Jayaprakash Narayan, too, applauded it, visiting Cuttack and studying this scheme.

No political theorist but a ground-zero realist, Biju displayed remarkable concern for the marginalised who make no demands and have no voice in power. The Constitution should consider the nation’s destitute. In 1990, he hiked daily wages of unskilled gig workers from Rs 11 to 25, on the suggestion of a poor old lady during electioneering in a remote village.

Frustrated with the lack of electric power to exploit mineral resources, he proposed reforming the power sector by gaining private participation – initially in generation, then in distribution. Odisha was the first state to reform the power sector. The State Electricity Board was dismantled, and regulation separated from generation, transmission and distribution. Mini-hydel projects were encouraged, as was electricity production based on wind power.

When chief minister in the 1990s, he asked people to thrash government officials who failed to perform. It was more a burst of frustration of an adventurer, angered at the snail pace of governance ecosystem that ignored concerns of common man and helpless poor. Odisha’s poverty ain’t pretty and governmental dole in various forms has only helped large swathes of lazy folks getting lazier. The gap between elites and poor lingers, only yawned wider. The maverick who frittered away his vast industrial empire to uplift the marginalised couldn’t live with this status quo in his final years. The laqeer ka fakeer was still alive.

His unconventional ways were well-known in Odisha. Right off his student days, when he rode his bicycle from Cuttack to Peshawar – 2,000 km each way. Or leaving his BSc course midway at Cuttack’s Ravenshaw College and joining the Delhi Flying Club and the Aeronautical Training Institute to train as a pilot in the early 1930s and earning his pilot’s licence in 1937, aged 21. Everything about him was flamboyant. Even his marriage in 1939 had the same flamboyance. “His marriage party arrived with a fleet of Tiger Moth planes which flew in formation over the train which carried the young couple to their honeymoon,” wrote The Independent.

Gita Mehta, Biju’s daughter, writes about his patriotism in Snakes and Ladders. When asked about his worst memory of British Raj, he said: “Once I was asked to fly a British Colonel and his adjutant to North-West Frontier. As I was climbing into the cockpit, he said very loudly, ‘My God! I am not going up in an airplane flown by a bloody native.’ Of course, he did not have any option. So I landed in a field about a hundred miles from Quetta, the hottest place in India during the summer. And it was damned hot in that field, without a tree for miles. The colonel was sweating and abusing the natives.”

“What did you do?” asked Gita.

Biju’s reply was so Biju. “Got back into the cockpit, told him to find someone who was not a bloody native to fly him, and took off, leaving him to walk to Quetta.”

Yet this stormy petrel of Indian politics didn’t tell the world what his chhappan-inch-ki-chhati did. But his authentic chhappan-inch-ka-kurta is on display, as are his tailor’s measurements at Biju Memorial in Cuttack. “Biju Patnaik was a very tall man,” said Subash Padhi, Biju’s tailor. “He had a 56-inch chest, a 27-inch shoulder, a 22-inch neck, and a 14-inch wrist. I’ve never seen such a gigantic figure.” He met the legend in 1972 when he visited the shop to get his kurta stitched. From 1972-1996, Padhi was his favourite tailor, stitching his all-white round-necked kurta. His chhati was real – not shambolic. No need to boast, no chest-thumping, no trumpeting, no indulgence in varying dress codes through the day to draw eyeballs. He did none of that. His dhoti and kurta stayed with him. Always.

Biju’s generosity was widely known. Very charitable and unstintingly helpful to the poor, he helped meritorious students. A progress card was all he asked for to know his help was used properly. No one came away empty-handed. He funded numerous students and sponsored many to study abroad in countries like Germany with advanced technological knowledge. A friend who was his secretary when he was chief minister in the 1990s told me about his vaunted generosity. An academic approached him for government funding to attend a conference abroad. Generous Biju readily agreed. All he had was an invitation letter from the organisers to present the paper, which Biju handed to his secretary. It had no more details. When his secretary read it and said they would have to seek more information before examining the proposal, Biju said he had already given the academic his word. Nothing more came from the applicant. Sometime later when no government funding could be provided, Biju told his secretary, “You guys didn’t support him, so I paid him with my own money!”

Biju was driven by an explosive, dynamic energy. Imperial and imperious, even whimsical at times, he was reckless as a politician. D.R. Mankekar in his biography of Lal Bahadur Shastri, while discussing the conundrum, After Nehru, Who?, wrote that so impressed was Nehru with Biju’s multi-faceted personality that for a while he considered Biju a worthy successor. But his loquacious tactlessness and indiscreet utterances, his plain speaking and temperamental flare-ups, shook Nehru’s fascination for him.

Sudhansu Mohanty, a former civil servant, is the author of the book Anatomy of a Tumour: A Patient’s Intimate Dialogue with the Scourge (Hay House India).